|

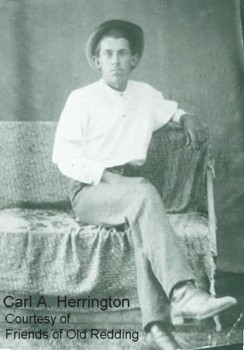

PVT. CARL A. HERRINGTON

Private Carl A. HERRINGTON of Redding answered his Country's call, serving with the 117th Infantry Regiment, 30th Division.

Private Carl A. HERRINGTON of Redding answered his Country's call, serving with the 117th Infantry Regiment, 30th Division.

Orders were received on May 2, 1918, to entrain for duty overseas, and on the night of May 10, 1918, the 117th Infantry went on board

HMS Northumberland at New York. The Northumberland, built in 1915 and scrapped in 1951, was a cargo ship owned by the Federal Steam Navigation Company and had for the most part been on the Australia, New Zealand and South Africa route before the war.

The 1,942 men of the 117th Infantry were the only men on board the Northumberland that trip so there must not have

been much space for troops. She was a cargo ship, thus accommodations on board were crude with the men were bunking

in the holds of the ship. Some ten days later, after an attack by submarines off the Irish Coast in which the convoy

escaped without loss, the HMS Northumberland docked at Liverpool, England, where special trains carried the

117th Infantry straight through London to Folkestone.

The 30th Division was one of seven American divisions which were concentrated in the British area for training and for

use in case the Germans made their threatened drive for the Channel ports. The 117th proceeded from Calais to Norbecourt,

where they trained strenuously for five weeks. About July 1st, the 30th Division was ordered to move into Belgium.

The 117th was assigned to Tunneling Camp, where it was given its final training in trench warfare. The 117th Infantry

was purely on the defensive while they were in Belgium. The Germans knew the location of every trench, and their

artillery played upon them day and night. Night bombers also made this a very uncomfortable sector, dropping tons of

explosives both upon the front and at the rear. There was little concealment on either side, because this part of

Belgium was very flat. Artificial camouflage provided what little deception was practiced upon the enemy. The casualties

of the 117th in the two months in which it was stationed in the Canal Sector were not heavy. Only a few men were killed,

and the number of wounded was less than 100.

On September 1, 1918, trucks and busses moved the 117th Infantry through Albert, Bray, and Peronne to near Tincourt,

just back of the celebrated Hindenburg Line. The 117th provided close support to the 118th Infantry which held the

front line. Casualties of the 117th were rather heavy from gas shells.

The attack upon this part of the line was set for the morning of September 29, 1918. The 27th American Division was on

the left, the 46th British on the right of the 30th American Division. The assault of the infantry upon the fortifications

of the Hindenburg Line was to be preceded by a bombardment of 72 hours -- with gas shells for 24 hours and with shell and

shrapnel from light and heavy artillery for 48 hours.

In the Thirtieth Division sector, the 119th and 120th Infantry were assigned to make the opening attack, with the 117th

Infantry following in close support and prepared to exploit their advance after the canal had been crossed. The 118th

Infantry was held in reserve. The 119th Infantry had the left half of the sector, while the 120th, strengthened by

Company H, of the 117th, covered the right half.

The plan of battle was that the 117th, following the 120th, should cross the canal between Bellicourt on the left and the

entrance to the canal on the right, then turn at right angles, and proceed southeasterly down the main Hindenburg Line

trench, mopping up this territory of the enemy for about a mile. Connection was to be made with the British on the right,

if they succeeded in crossing the canal. However most of the assaulting companies became badly confused due to a deep fog and smoke,

strayed off somewhat from their objectives, and their attack swung to the left of the sector. The 117th, which followed,

went off in the opposite direction fortunately and cleaned out a territory which otherwise would have been left

undisturbed. While it caused endless confusion and the temporary intermingling of platoons, companies, and even

regiments, the deep fog contributed to the American's success.

The Germans did not know how to shoot accurately, unable to see the Americans. Men in the combat groups joined hands

to avoid being lost from each other. Officers were compelled, in orienting their maps, to lay them on the ground, as it was

impossible to read them while standing in the dense cloud of smoke and mist. The atmosphere did not clear up completely

until after the canal had been crossed.

The tanks were separated from the infantry, but their work was invaluable in

plowing through barbed wire. Due to the dense fog, a majority of the tanks had become disabled before noon.

The casualties of the 117th on September 29 were 26 officers and 366 men. Seven field pieces, 99 machine guns, 7

anti-tank rifles, many small arms and 592 German prisoners were the trophies of the day. Had it been a clear day,

casualties would have easily been doubled.

The 59th Brigade next offensive was launched the following morning, October 8, with the 117th on the left, the 118th on

the right and the British were on their flanks. The jumping off line was northeast of Wiancourt, while the objective was

slightly beyond Premont. The 1st Battalion of the 117th launched the attack for the regiment with the 2nd Battalion

in close support. The 3rd Battalion, which had suffered severely the previous before, was in reserve. The attack

got off on time in spite of the difficulties that were encountered the previous night in getting into position under

fire and in the dark.

In the face of furious German resistance with all kinds of machine gun nests and an abundance of light artillery, the

battalions advanced very rapidly, knocking out machine guns and maneuvering to the best advantage over the

broken ground. The 2nd Battalion suffered heavy losses during the morning and two companies of the brigade reserve

were ordered to its support. Before noon 2nd Battalion Commander Major Hathaway, announced the capture of Premont and

his arrival at the prescribed objective. Positions were consolidated during the afternoon and preparations made for a

possible counter-attack.

The casualties of the 117th on October 8 were the heaviest of any day of fighting in which it was engaged on the front.

During these three days of fighting, October 7, 8, and 9, the regiment lost 34 officers and 1051 men as casualties.

PVT. HERRINGTON lost his life on October 8, 1918 in France. He was interred at Somme American Cemetery,

Plot A, Row 26, Grave 5.

The World War I Somme American Cemetery is located one-half mile southwest of the village of Bony (Aisne), France.

This fourteen-acre cemetery, sited on a gentle slope typical of the open, rolling Picardy countryside contains the graves of 1,844 American military Dead. Most lost their lives while serving in American units attached to British Armies or in the operations near Cantigny during World War I.

Redding, Iowa's American Legion Post was named in honor of PVT. Carl A. HERRINGTON.

SOURCES:

http://freepages.military.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cacunithistories/117th_Infantry.html

../../../greatwar/cemeteries/Somme-Cemetery.htm

Submission and PVT. HERRINGTON'S photograph courtesy of Friends of Old Redding, 2010; Compilation by Sharon R. Becker

To contribute to Ringgold County's soldier pages,

contact

The County Coordinator.

Please include the word "Ringgold" in the subject line. Thank you.

|