|

TALES from the FRONT PORCH

Ringgold County's Oral Legend & Memories Project

LETTERS WRITTEN by GLADYS (TENNANT) PRENTIS

ABOUT HER LIFE to HER CHILDREN and GRANDCHILDREN

September 7, 1975 - February, 1984

ONE ROOM SCHOOLS, 1908 - 1913

September 7, 1975

I started to school in California city schools, and had never heard of a one room school until my family moved to Iowa

when I was nine years old. I was in the fourth grade. There were probably thirty students in my room in California. In

the school in iowa there were about twenty students total — first grade through eighth grade.

The desks were double desks—two children shared the seat and desk space. When a class was called to recite, they went to

the front of the room to a long seat called the recitating bench, just in front of the teacher's desk. All the children in

the school could hear every class lesson and were often able to advance rapidly by learning from the other children.

At recess time the teacher went out in the school yard and played with the children—or helped to keep peace between the

"big kids and the little kids," or between the girls and the boys.

Everyone brought lunch in a small bucket or box. It was always cold. No hot lunches! Not so bad in the fall and spring,

but left much to be desired in the winter. Heat was from a stove located in about the center of the room. Close to the

stove you were too hot — farther away, you were too cold. the teacher was the janitor, — started fires, swept out and

dusted. The big boys often helped carry in the coal or wood for the stove. And as a special favor, some children were

allowed to stay after school and clean the blackboards and erasers.

Everyone brought lunch in a small bucket or box. It was always cold. No hot lunches! Not so bad in the fall and spring,

but left much to be desired in the winter. Heat was from a stove located in about the center of the room. Close to the

stove you were too hot — farther away, you were too cold. the teacher was the janitor, — started fires, swept out and

dusted. The big boys often helped carry in the coal or wood for the stove. And as a special favor, some children were

allowed to stay after school and clean the blackboards and erasers.

We didn't have regular classes on Friday afternoons after recess. We would have spelling bees, geographical quizzes, or

arithmetic matches. Or sometimes we would sing. Our school day always opened with a song, a salute to the flag, and

generally we would have scripture reading and prayer. The "opening exercises" depended on the teacher's likes or

dislikes. If we got through our lessons early, the teachers would read to us or we could go to our little library, —

probably only a few books the parents of the children had sent to school from their own meager supply of books. The

books we read were Black Beauty, Pilgrim's Progress, Robinson Crusoe, Little Men, Little Women, Uncle Tom's Cabin, The

Call of the Wild, and of course many others. It was a sweet, peaceful, uncomplicated world that I grew up in before the

First World War. The songs we sang were mostly Civil War songs, — Tenting Tonight; Massa's in the Cold, Cold, Ground;

Tramp, Tramp, Tramp the Boys are Marching, etc., and the Stephen Foster songs, — My Old Kentucky Home, Swanee River,

Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair, etc., etc.

In February and May the 8th grade students took the state examination so they could go to High School. Most rural schools

were only eight month terms, so school was out in April. The only ones who took the exams in May were the ones that had

failing grades in the February tests. I had to take Arithmetic and Grammar in May because I had failing grades. I did

manage to squeeze through in May. Now you don't have grammar and arithmetic — it is math and English.

I went to High School and took a Teacher Training course and taught in rural schools for two years, — just a high school

graduate. I was eighteen years old, and I had students who were seventeen years old. I stayed at home and each evening

my father helped me prepare my lessons for the next day. I could never have gotten through the year without my father's

help. I wonder now how much the children learned that year! But the Director wanted me to teach there again the next year.

World War I had started, and I signed up to become an army nurse. I would have been worse at that than at teaching.

Another school close to my home had no teacher when it came time for school to start, so they asked if I would, please,

teach until my orders came, and I did. I got $90.00 a month and that was inflation. Most teachers got $40.00 or $50.00.

then the Armistice was signed and the war was over, so I taught all year.

Games we played at school were Fox and Geese (in the snow), sledding, jacks, Drop the Handkerchief, and Last Couple Out.

We had a water bucket. Sometimes there was a well on the schol grounds or we got it from the nearest farm house. We all

used a common dipper, — no wonder we all had colds all winter long!

(Other old songs were Dixie, Old Black Joe, and Battle Hymn of the Republic.)

(Nana) Mrs. X. T. Prentis

Mount Ayr, Iowa

Although I'd heard many of Nana's interesting stories numerous times over the years, In February 1984, I wrote Nana

asking some specific questions so that I could have a record of some of them in writing in her own words. Those questions

and her responses are as follows:

Where and when did you teach school?

I didn't intend to teach school. I wanted to do something else, but it was war time. They wouldn't let girls join the

army in those days, so I signed up as a nurse, and took my examination and passed. In the meantime, before I was called,

I taught school at Silver Point, two miles north of our home in Rice Township. I drove a horse and buggy, and unhitched

and kept the horse in an empty barn which was across the road from the school. I lived at home, and with my father's help,

I was able to get through one year of teaching. My salary the first year was $90.00 a month, pretty good wages for those

days. That year I had 30 pupils in every grade including Primer (Kindergarten) through the 8th — except 3rd grade. I was

eighteen years old and had a seventeen-year-old student.

I didn't sign up for another year, because I was sure I would go soon, as an army nurse, but the Director, Mr. Milligan,

of Lonesome Hollow School, which was a mile and 3/4 from our home, came and asked me if I would teach school at Lonesome

Hollow until I'd get my call to go to Nurses training. I said yes I would do that. I taught until Nov. 11, when the

Armistice was signed, and there was no more need for Nurses training. Mr. Milligan drove (with a horse and buggy) to the

school house and told me to dismiss school, — that the war was over. I ran a mile and 3/4 to tell my folks that the was was

over, but they had already heard it. My two brothers, Carl and Maurice, were both on the front lines, fighting in France.

X was in the Army too, but was stationed at Fort Des Moines. We immediately began to make plans to be married and set the

date for June 12, 1919. I, of course, finished out my school year.

Before X joined the army, he had worked for the Immigration Service, and was to go there again after the war, to work in

the Office of Immigration Service in Sioux City. Then Congress failed to appropriate any money to continue the Immigration

Service. The office in Sioux City closed before Dad got a paycheck for the work he had done, and certainly had no money

saved from $30.00 a month army pay. He wouldn't call me to bring him money, so he bought a bottle of milk and a loaf of

bread and lived on it for two days until he got a check for a few days work with a construction company. Then he came on

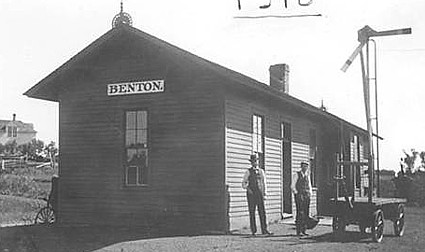

the train to Benton and walked four and a half miles to our house.

How did you and Granddad meet?

In 1913, I graduated from the eighth grade and X did too. We were both in Rice Township, but in different schools. In those

days, 8th grade graduation was almost as important as high school graduation is today. Delphos had band concerts every

Saturday night, and X had seen me when I would go to the concerts with Maurice, who played in the band, but I had not yet

seen him. So 8th grade graduation was at a church in Delphos for all of Rice Township. There were a number of girls

(probably 10 or 15), but only two boys, — X. T. Prentis and Otto Haley. We had one rehearsal. I knew several of the girls

from other schools. Then, as now, I couldn't keep my mouth shut. We had two lines going into the church, and I suggested

the boys be at the end of the line, bringing up the rear. As it turned out, the girls were in alphabetical order, and T

(Tennant) was at the end of the line. Then the girls all made fun of me, because, they said, I just wanted to sit by one

of the boys. It turned out to be X. T. Prentis. This graduation was the 14th of June. Many years later, when we were

planning our wedding date, we wanted it in June and we thought about the 14th, but that turned out to be a Saturday, — and

nobody, but nobody ever got married on Saturday. So — my grandmother's birthday was June 12, so we settled on that date.

That was Thursday, and acceptable.

Then in the fall, when we both started to high school in Mount Ayr, — we went to high school then just like kids go to

college now. Maurice and I had rooms together in a home, and X and Otto roomed together. And through the four years of

high school, we dated spasmodically.

When the movie THE BIRTH OF A NATION was coming to town, admission was $1.00. My father would give me a quarter

each week for my spending money. That was for pencils and paper and anything else I needed at school. so the only way I

could possibly go to the show was to get a date. By that time Maurice had graduated from high school and I was rooming

with Gladys Jacobs. Gladys Stuck and Elsie Richardson also had rooms at the same house, so that made three Gladys' at the

same house. Gladys Jacobs was Jake, I was Ten, but Stuck we couldn't do a thing with, so she was just Gladys. One night

the telephone call came for Ten, so I went and answered, and someone said, "Would you like to go to the show??" And I

said "Yes" and he hung up. I went upstairs and said, "I've got a date for the Birth of a Nation," and of course the

girls asked, "Who?" And I said, "I don't know" (sheepishly). So the girls got with X the next morning and asked him if he

called me and he said yes. and so they conspired with him—and he wasn't to tell me he called me. He said to me, "What's

this I hear about you making dates with people you don't know?" And they all kept me in hot water until the night of the

date... and it was X! X worked at the Record News office as a typesetter, janitor, reporter, etc. He sometimes met the

train and interviewed the arriving or departing passengers, so he had a salary and that's how he could afford to take me.

He didn't get any money from his folks.

When the movie THE BIRTH OF A NATION was coming to town, admission was $1.00. My father would give me a quarter

each week for my spending money. That was for pencils and paper and anything else I needed at school. so the only way I

could possibly go to the show was to get a date. By that time Maurice had graduated from high school and I was rooming

with Gladys Jacobs. Gladys Stuck and Elsie Richardson also had rooms at the same house, so that made three Gladys' at the

same house. Gladys Jacobs was Jake, I was Ten, but Stuck we couldn't do a thing with, so she was just Gladys. One night

the telephone call came for Ten, so I went and answered, and someone said, "Would you like to go to the show??" And I

said "Yes" and he hung up. I went upstairs and said, "I've got a date for the Birth of a Nation," and of course the

girls asked, "Who?" And I said, "I don't know" (sheepishly). So the girls got with X the next morning and asked him if he

called me and he said yes. and so they conspired with him—and he wasn't to tell me he called me. He said to me, "What's

this I hear about you making dates with people you don't know?" And they all kept me in hot water until the night of the

date... and it was X! X worked at the Record News office as a typesetter, janitor, reporter, etc. He sometimes met the

train and interviewed the arriving or departing passengers, so he had a salary and that's how he could afford to take me.

He didn't get any money from his folks.

My father didn't think it was necessary for a girl to go to high school, but Maurice insisted that I should go to high

school, and that's the only reason I got to go. They rented two rooms and moved furniture in, and gave me a privilege of

charging my groceries, but Maurice said I didn't know they had anything at the grocery store but cookies and bananas. I

was only 14 years old, and was supposed to do the cooking for the two of us, but I didn't know anything about it. I had

always been the errand girl, —carried in the cobs to start the fires, carried the water from the well, gathered eggs in

the evening, ran to the cellar to get things for Mama, and running up and down the stairs for Mama and Edna who was lame

and couldn't do those things, and Mama had a bad heart. Then at Christmastime, my grandfather Tennant died, and Maurice

went someplace else to stay, and I went to Grandma's to stay. She told me a lot of history and background things that I

might never have known otherwise.

What can you tell me about Dad when he was little?

Your dad was born about a month early, and was very sick at the time of his birth. He was born at home. Dr. Hill and the

practical nurse, Mrs. McKey and Dad were there to help with the birth. Raymond's digestive tract was immature and his

bowel movements would be bloody, and after nursing, he would vomit up blood. X called the Dr. several times, and finally

the Dr. told him, "I can't do anything more for your baby," so X said, "Well, we'll take care of him ourselves." Our dear

Anne spoke up and said, "Daddy, don't you think we ought to pray?" So X, Anne, Richard and little Jean went into the

living room (the big house across the street, west from the Baptist Church), knelt and prayed. Their prayers were

answered. X came home from the hatchery (about a block away from where we lived) every hour and fed Raymond with an eye

dropper, using my milk. We had a hired girl who lived with us and went to high school, and the nurse, but Dad himself did

it. This went on for about two or three weeks and then the Doctor noticed there was trouble with Raymond's eyes. In the

problems at the time of the birth, the Dr. probably had neglected to put in the necessary eye drops. so we took him to

Creston to the hospital (as we had no hospital in Mount Ayr until much later). Raymond and I stayed in the hospital for

several weeks. The doctors up there said they could save his life, but they did not think they could save his eyesight.

I remember wondering how you could explain a rainbow to a baby who didn't know what color was.

Dad came to the hospital as often as he could, but for me, the days dragged by in a terrible way. Raymond's eyes did

improve, though, as you know. His eyesight is not good, but we are so thankful for what he has.

On May 1 following Raymond's birth, we made May Baskets, and Anne didn't feel well. As we delivered them, she stood there

and let every kid in town (it seemed to me) kiss her. When a basket was delivered to a house, the one receiving the basket

could kiss the giver, if he could catch her or him. Well, the next day the Doctor quarantined our house for Scarlet Fever.

Some official from town came and nailed a sign on our house. RED (the dreaded red) for Scarlet Fever, yellow for Chicken

Pox, pink for mumps, etc.,—and you could not leave the house, nor could anyone come in while the sign was up. The doctor

said that Raymond could not endure Scarlet Fever and asked if I could send him away someplace. So my mother, Grandma

Tennant, took Raymond and weaned him instantly, and kept him for six weeks. X also had to stay away. He brought us

groceries and left them at the door, and then we talked through closed windows with him, and they would bring the baby

to the window sometimes and let us see him. Raymond had a hard start in life. We called him our "wonder baby." He rounded

out our family, —two boys and two girls. Every child then had a brother and a sister. To me that is a perfect family. It

was also the kind of a family I had grown up in, and also the same for each of my parents.

What do you remember about living during the Depression?

The Depression was bad, but not as bad as many places, because most farmers had milk, eggs, chickens, a garden, and could

live fairly comfortably. But the Depression coupled with several years' drought, made it very difficult. We were just

starting the hatchery business. Chickens would hatch, and the farmers wanted them. We couldn't afford to keep them and

feed them, so we let the farmers have them on credit. Many of those bills were never paid. We turned off our electricity

and used coal oil lamps, stored the electric stove on the enclosed porch, and used a coal oil cooking stove. We made our

own bread, churned butter from the old cow (Daisy) that kept us in milk, cream, butter, cottage cheese, and ice cream. I

skimmed the cream off as much as possible, and yes, the skimmed milk was "blue."

My brother, Maurice and his wife Emma, lived in Detroit, Michigan. He was laid off from his job and they really were hard

hit in the Depression. My mother sent boxes of food sometimes to them. Finally, they were able to manage an apartment

building and got their apartment for that, and Uncle Maurice sold and bought old gold and silver door to door. At times,

they were almost desperate! About the silver and gold: the people needed money so badly that they would take off their

wedding rings and sell any jewelry or silver in the house.

Who taught you to knit?

My mother taught me how to knit when I was eleven years old. I thought knitting was going to be a lost art, and I'd

better learn how. But I never knit much until Anne got out of high school. Knitting has been my joy and consolation all

the years since.

How many homes have you had?

After we were married, we moved every year, — renting for $15 or $20 a month, until we bought our home when Raymond was

six months old, in 1930. that is the house where Richard and Marj still live. That house and all the land where the

hatchery is, cost $2,000.00. There was no electricity or water in the house, but we had those put in before we moved. We

lived there until 1950, when we moved out to the place where we are now, which was where the original house burned, and

then re-built. The hatchery was built in about 1944 during the war. I believe X had the first Jeep in Mount Ayr. The fire

that burned our home down was Thanksgiving night in 1955.

Why don't you go by your first name, Victoria?

I was born during Queen Victoria's reign in England. My mother was English, and Gladys was a fairly new, sophisticated

and popular name of the day. My mother thought that "V. Gladys" would be such an "elegant" signature, but I was not an

elegant child, and not an elegant woman, and I have never signed my name in that way, but Queen Victoria died on my

birthday when I was two years old.

What are some of the poems you have written?

I'm not a poet. I just write doggerel, which the dictionary says is "trivial, awkwardly written verse." Jean Reger's

newspaper used to have a column called VERSE OR WORSE and mine was worse.

- Victoria "Gladys" TENNANT PRENTIS (1899 - 1988)

Contribution by Julie Watts, August of 2009

Visit Fanflower's

Tangled Roots site at ancestry.com for additional information on the PRENTIS Family

|