The Destination Reached.

Passing Mr.

Mason by, we found ourselves in a few moments on the ground which

was to be our future home. At the point of the ridge near the foot of

the mound, which in later years, has been extensively known as

Judge Green’s Mound Farm, we pitched our tent, the little brook

near by affording us water, and the grove close at hand, furnishing us

wood and poles and bushes for the erection of a bower, which, for a

few days, was to serve us as a kitchen and dining room.

The Claim Described.

Our claim

embraced a half section, 320 acres, the south line being the same as

the north line of what is now known as the Bever farm, one corner of

the west line being in Central Park, and the other on the east side of

the mound near the bottom, the north line running from this latter

point through Midway Park about a quarter of a mile east of the

Boulevard into the woods.

Hobson’s Choice.

The land on every

side except the east, had already been claimed, and so it was Hobson’s

choice; this or nothing. But my parents could not have been better

satisfied if they had had the whole country to choose from.

The exact

description of the land when it was surveyed, three years later, was

found to be the southwest quarter of section 14, township 83, north of

range 7, west of the fifth principal meridian, and the southeast

quarter of section 15, same township, range and meridian.

My mother rode on

horseback while she accompanied father and some of the neighbors as

they looked over the boundaries of our claim and selected the location

for the house.

The Erection of the First Cabin.

The next step

after pitching our tent, and putting up our bower, was to build a log

cabin, which would serve us for the time as a temporary dwelling

place, and could afterwards be used as a stable for our horses when a

more commodious house could be erected. It took about ten days to

erect a cabin. It stood on the east side of the road near Mr. Bower’s

nursery, on the boulevard, one and a half miles from the river. It was

a very primitive looking structure, 16 by 18, perhaps, with what we

called a cob roof made of clapboards, with logs on top to hold them in

place. It was quite an agreeable change from our tent and wagons when

we entered this new cabin, although there was not a great deal of room

to spare after our goods were unloaded and the nine members of the

family were gathered within its walls. When the table was spread there

was no passing from one side to the other except as we got down upon

our hands and knees and crawled under, an operation easily performed

by us children.

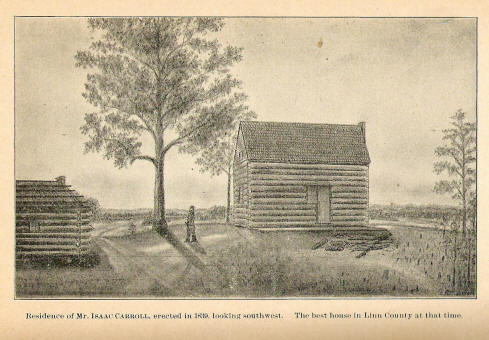

The Permanent Home.

Having become

fairly settled in this little domicile, the next great work which was

to occupy the whole summer and fall, was the erection of the building

that was to be our permanent home. There being no mills nor lumber in

the country, of course we must build our house of logs. It was however

not to be any common kind of a cabin, it was to be a somewhat

ambitious structure for the time, in fact it was to be the best house

in Linn county, and when completed, it enjoyed that distinction. It

was said that there was nothing in the county that equaled it.

The dimensions of

this house were 16 by 24 and a story and a half high. There were in

the walls of this house between 50 and 60 white oak logs, most of them

quite straight and free from knots. The ends of the logs were cut off

square and the corners were laid up like square blocks, care being

taken to cut off enough at the ends to allow the logs to come as close

together as possible, so as to leave but little space for chinking and

plastering when it came to finishing up. The only boards about the

entire building were in the door which I think were brought with us on

top of our wagon box, which was of extra height. The joists above and

below were made of logs, the upper ones squared with the broad axe.

The casings of

doors and windows and the floors above and below were made out of bass

wood puncheons. Slabs were split out of the logs and then hewn out

with the broad axe and the edges were made straight by the use of the

chalk line.

The gable ends

were sided up with clapboards rived out of oak timber three or four

feet long and then shaved off smooth like siding. The rafters were

made of hickory poles, trimmed off straight on the upper side, and

strips three or four inches wide, were nailed on the sheeting.

Upon these

strips, shingles made of oak, 18 inches long, and nicely shaven, were

laid. The logs of the walls, in the inside were hewn off flat, and the

interstices between, were chinked and plastered with lime mortar, the

lime being burned by my father on Indian Creek. There were three

windows below of 12 lights each, with glass 7 by 9, and a window in

each of the gable ends of 9 lights, which furnished light for the room

above. The fire-place was built up of logs on the outside, and lined

with stone within, and the chimney was built of sticks split out about

the size of laths, and plastered with clay both inside and outside.

Another incident

in connection with this fire-place, of which my sister reminds me, is

that mother was the builder of the stone work. Owing to sickness in

the family the work on the house had been delayed till winter was at

hand, and the occupancy of the new house at the earliest possible date

seemed a necessity. A thousand things pressed upon us all at once, and

every hand that was able to work was busy from morning till night.

Mother thought she saw an opportunity to help in the matter of the

fire-place, and so she laid up the stones with her own hands, while

the girls, Sarah and Kate, furnished the clay mortar, and rendered

such other assistance as was required.

Mother was always

delicate in health and was really not fitted for any very hard

physical toil. She was, however, quick in her movements, and her

vigorous mind and her exhaustless courage and grit made up for all

bodily deficiencies, and prepared her to meet every emergency.

The door had no

“latch string to hang out.” But it had a genuine handle with thumb

piece and latch, all of wood and the handiwork of my father, who, by

the way, possessed considerable mechanical ingenuity. He rived and

shaved most of the shingles on a shaving horse of his own manufacture;

he could make a splint broom, bottom chairs with black ask splints,

make rakes, wooden pitchforks, and could even make a good strong sled,

and many other useful things in those times when everything had to be

manufactured from the raw material.

Few can

understand the difficulties and obstacles to be overcome in the

erection of a building even of such small proportions as the one I

have just described. In the first place we traded off one span of our

horses for two yoke of oxen, which latter seemed indispensable in

working among the logs, and in much of the work in opening a new farm.

Then it was no small job to select nice straight trees scattered here

and there through the forest, some near and some far away. Then they

had to be cut down and drawn in one by one with the oxen, the vehicle

used being what was called a “lizard,” a sort of a short sled made in

the form of the letter A, one end of the log being chained to the

cross piece and the other dragging on the ground.

The raising of

the house was a time of great interest, not only to our own family but

to everybody in the neighborhood for miles around. Everybody turned

out to the raising, and great care was taken to lay up the corners

square and plumb, and when the last log was shoved up on the skids to

its destined place, it was a time of general rejoicing among the weary

workmen who had labored so faithfully and so willingly during the

day.

Mr. Joseph

Listebarger, who was a carpenter and joiner, from the west side of

the river, did the carpenter work and the finishing.

I have described

the building of this house thus minutely to show in a limited way some

of the obstacles and hardships that had to be encountered by the early

settlers of this country.

The building of

that house at such a time, small as it was and as insignificant as it

seems from our present standpoint, was a real triumph, and exhibits an

amount of pluck and energy and perseverance that no one need be

ashamed of. And this appears the more readily when we remember that

every foot of ground had to be cleared of brush and small oak trees,

that roads had to be made, that provisions for our large family had to

be brought from the Mississippi river, and, that during the latter

part of that summer, there were times when every member of the family

was prostrated with the ague except my brother Charles and myself.

|