|

A part of the IAGenWeb and USGenWeb Projects Moyer/Cholera/Shafer/Hurd Cemetery |

|

|

A part of the IAGenWeb and USGenWeb Projects Moyer/Cholera/Shafer/Hurd Cemetery |

|

Location: Penn Township, section 19. Difficult to find off of 142nd Street, 3/4 mile off the road. No path back through the CRP ground with thistles and goldenrod growing as high as the car... (see township map.)

Burials: 1845 to 1900.

Condition: Renovated in 2018/2019.

Mowed: Mowed periodically.

Photos taken Sept. 2002

"The Southeast Iowa Union / Fairfield Ledger"

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

Front Page, Page 2 and Page 7

Fairfield woman renovates pioneer cemetery

By Andy Hallman, The Union

FAIRFIELD - A pioneer cemetery north of Fairfield has been completely renovated thanks to the work of rural Fairfield resident Barb Sieren.

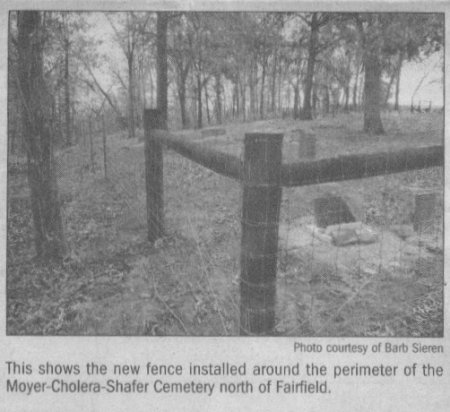

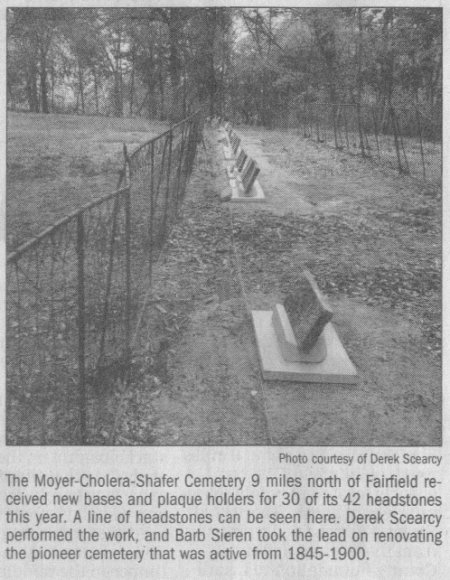

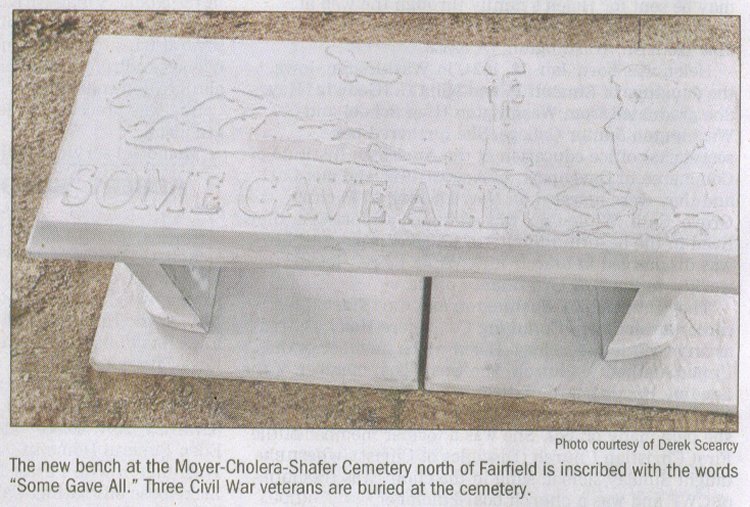

Sieren cleaned up the 150-year-old Moyer-Cholera-Shafer Cemetery about 9 miles north of Fairfield. The cemetery is located in a field three-quarters of a mile from 142nd Street. She received a grant from the Greater Jefferson County Foundation to install new foundations for 30 of the 42 headstones at the cemetery, put a new fence around the perimeter and install a new bench. Derek Scearcy, owner of Scearcy Ornamentals of Fairfield, made and installed the bases, bench and plaque holders. The fence was installed by Harbison Fencing of Brighton.

Sieren began this project in the spring of 2018. She spent many hours clearing brush from the cemetery, getting help from her husband, Rick, and a few neighbors to do the heavy lifting and cutting the large fallen trees.

Every Memorial Day and Veterans Day, flags and a veterans' marker are placed at the graves of Civil War veterans buried there, namely James H. Baker, William A. Lydick and Bazell E. Wiggins.

The first plot in the cemetery is from 1845, and the last one appears to be from 1900, unless there are more recent headstones that have been buried with the passage of time.

Beginning

Barb Sieren lives seven miles north of Fairfield. For the past 15 years, she's heard so many people in the area mention that somebody ought to clean up the old cemetery on 142nd Street. But nobody ever got around to it. Sieren said it appeared to her that the cemetery hadn't been cleared for 50 years.

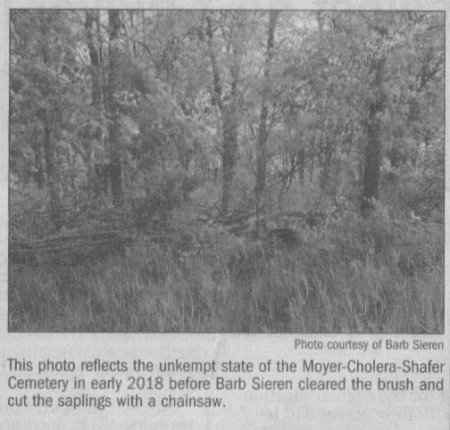

One day in the spring of 2018, Sieren said to herself, "This is a really good day to start cleaning up the cemetery." At that time, the cemetery was barely recognizable as a cemetery apart from the road sign indicating its location. It looked like a patch of timber in the middle of a field, and nothing more.

"I went home and got my chainsaw and trimmers. I told my husband what I wanted to do, and he said, 'Be careful out there' and I said back, 'I'll be fine!'" Sieren said.

Sieren estimates that she put about 20-plus hours of work that week into clearing the trees and bushes.

"There were so many saplings and little cedar trees that had grown up around the stones. I had a great big pile of brush we ended up burning," she said.

Sieren and volunteer John Gevock uncovered 42 stones in the cemetery. Of those, about 30 had broken off from their foundations or were lying on the ground with nothing holding them up.

Grant

The following spring, Sieren posted on her Facebook page that she was headed out to clean up the cemetery once more. She received a message from Barbara Kistler of the Greater Jefferson County Foundation. Kistler suggested she apply for a grant from the foundation to reset the headstones on a proper foundation. She gave Sieren the names of organizations she could use as a 501c fiscal agent that could receive the grant.

Sieren contacted Mark Shafer, curator of the Carnegie Historical Museum in Fairfield, to see if the museum board would be willing to be her fiscal agent. The board acquiesced, and Shafer took the opportunity to invite Sieren to join the board, which she has.

Scearcy

Upon receiving the grant, Sieren contacted Derek Scearcy to see if he would be willing to help her right the headstones so they wouldn't sink into the ground. Scearcy said that, if Sieren wanted the headstones done according to modern specifications, it would be expensive. Modern foundations require digging four feet into the ground. Scearcy said that getting contrete trucks to the site wouldn't be easy, either, because the cemetery was only accessible through a grass lane.

That's when Scearcy and Sieren began talking about an alternative. Scearcy showed her that he could make 18 by 24 inch concrete pads and plaque holders that the headstones could rest on. She liked it, and he was able to pour all of those pieces at his shop and transport them to the cemetery on a trailer.

After the holes were dug, Sieren laid a limestone foundation so that Scearcy could top them off with the concrete pads and plaque holders. The headstones were laid horizontally on the plaque holders because Sieren and Scearcy felt it wasn't safe for headstones so old and fragile to sit vertically, making them liable to fall. All of the bases and plaque holders were installed Aug. 31, 2019.

"Not everybody you come across will take it upon themselves to do that kind of work on their own time," Scearcy said about Sieren's efforts. "Even if people around here might not know they have relatives buried in an old cemetery, it should still be done."

History of cemetery

The cemetery is named "cholera" after the disease that killed many of the first people buried there. Cholera is a highly infectious disease that causes severe watery diarrhea, which can lead to dehydration and death if untreated.

The Fairfield Tribune printed an article in 1899 in which the story of the cholera outbreak of 1851 was recounted by Col. W.S. Moore, a former Fairfield resident.

The Tribune article states that a young man named Michael Shafer was visiting the town of Keokuk in the summer of 1851, there to fetch goods for the merchants in Fairfield.

"At that time, cholera was more or less prevalent in all parts of the United States, and was especially destructive of life in the cities and towns along the Mississippi River," the Tribune stated.

Shafer likely contracted cholera during his visit to Keokuk and brought it back with him when he returned to Jefferson County, specifically to a hamlet of homes about 6 miles north of Fairfield where he lived.

The cholera outbreak occurred on July 2 that year. Over the next three days, three of Michael Shafer's family members died, one after the other. First it was his father Solomon, then his mother, Polly, and later his brother, Leander. Michael himself survived the disease and was still living at the time of the 1899 newspaper article written 48 years later.

Relatives of the Shafers who came to visit them in their hour of need, such as the Haywood family, contracted the disease and died within a matter of days, too. Solomon Shafer's brother-in-law Elijah Stevens was "pronounced dead and was prepared for burial, but subsequently came to life and died 20 years ago at the advanced age of 90 years," the Tribune printed. "He is remembered as a jovial, kindly man, who enjoyed living, and the kind of person who would not yield to the grip of the grim monster prematurely, as it is evident he did not."

Moore writes in his reminiscing article that one man in the neighborhood names Charles Blakely was a "noble old hero" who, upon the breakout of the epidemic, "at once threw himself into the breach, and nursed the stricken neighbors and assisted in their burial."

Moore writes that Blakely was probably the "only neighbor, aside from relatives, who had the courage to enter the sick chambers, and he seems to have been providentially saved from attack by the fatal complaint." Moore adds that Blakely was a one-armed man known to almost everybody in Jefferson County.

Why Moyer?

One of the oddities of the cemetery is that it's not clear why it contains the name "Moyer" since no Moyers are buried there. The Union asked several local historians to try to solve the mystery. Mark Shafer (who does not recall any relation to the Shafers the cemetery is named after) said he has a vague memory of his mother referring to a church in the area as the "Moyer Chapel," which later became known as the Pleasant Grove Methodist Church.

"When my dad took us out to look at the cemetery in 1965 when we were kids, the name 'Shafer' never came up," Mark said. "He just called it the 'cholera cemetery.'"

Local historians Stan Plum and Richard Thompson suggested that perhaps someone named Moyer owned land in that area, and that's how the cemetery acquired the name. Historian Verda Baird said she had always wanted to catalog all the churches in Jefferson County's history. If she had, she might know the answer.

"I thought I would get around to it, but this old woman got worn out," she joked.

Baird said there are 77 rural cemeteries in Jefferson County and that 51 of them are considered "pioneer" because they have not had any burials in the past five years.

Thompson visited the Moyer-Cholera-Schafer cemetery in 2007-2009 and again in 2011-2012 to take photographs of the headstones, which he put in a picture book that now sits in the Fairfield Public Library in its genealogy section. Sieren contacted Thompson about his book, which has been updated to reflect the renovations.