|

Parsons College's Rise and Fall, 1875 - 1973, and Long-Time Faculty Look Back, 2018 |

|

|

Parsons College's Rise and Fall, 1875 - 1973, and Long-Time Faculty Look Back, 2018 |

|

Parsons: 98 Years Of Service

Life And Death Of A College

From The Fairfield Ledger

Friday, June 1, 1973

By Dean Gabbert

A New York merchant started it all and New York preacher -- in the minds of many -- finished it.

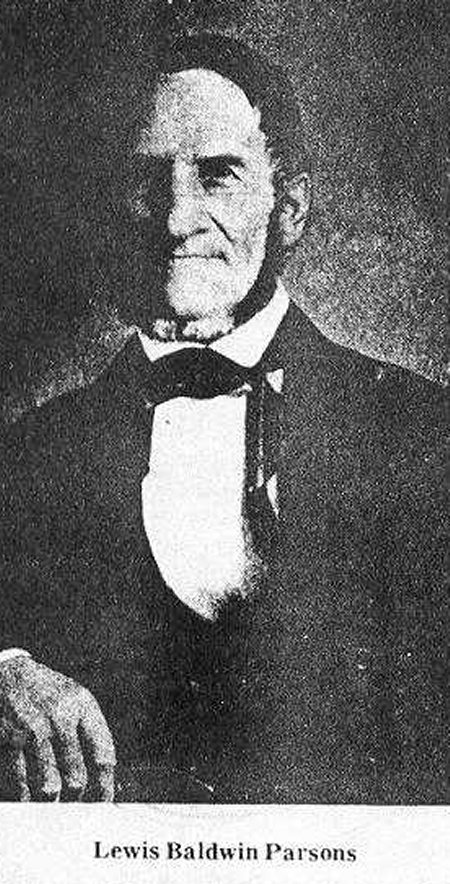

The merchant was Lewis Baldwin Parsons who rode through Fairfield in 1855 without knowing that the frontier village would become the site of a college bearing his name.

The preacher was Millard G. Roberts, who arrived in Fairfield exactly 100 years later and made Parsons the most talked-about college in America. But after 12 years his academic empire collapsed, leaving the school a legacy of problems and debts from which it never recovered.

Lewis Parsons came West to see the country and perhaps improve his failing health. He liked what he saw in the young state of Iowa and he stopped long enough to buy some prairie land at the bargain price of $1.50 per acre.

His son, Charles, was already a resident of Keokuk and this may have been a factor in his interest in the Hawkeye state. Parsons' visit to Fairfield was mentioned briefly in a letter to Charles Parsons describing his travels.

A few months later Parsons penned his will at his home in Governeur, N.Y., directing that his estate to be used "to endow an institution of learning in the State of Iowa."

Parsons died on Dec. 21, 1855 and 13 years passed before his executors made their first visit to Iowa to implement his will. Selection of the site was left to them with the stipulation that the college be placed under the control and supervision of the Presbyterian Church. Cedar Rapids, Marshalltown and Des Moines were the first three cities to be considered and rejected by a location committee composed of representatives of Iowa's two Presbyterian synods.

Fairfield did not enter the picture until Nov. 24, 1874 when the committee visited the town at the invitation of a group of local citizens headed by the Rev. Carson Reed, pastor of the Presbyterian Church. Three weeks later the committee made its decision: the new college would be located in Fairfield if its citizens could raise the sum of $27,000 by public subscription within two weeks.

Overnight, Parsons College became the concern of the entire community. Meetings were held, a campaign was launched and when the deadline arrived, the goal was reached with $516.25 to spare.

The Parsons estate included extensive land holdings in seven Iowa counties, but at the time of the founding of the college, only $4,016.65 was available in cash. Ultimately, the estate yielded about $37,000.

Officially, Parsons College came into being on Feb. 24, 1875 when 15 newly-appointed trustees met in Fairfield and adopted articles of association. Five of them, James F. Wilson, Charles Negus, William Elliott, George A. Wells and Carson Reed, were residents of Fairfield.

Lewis B. Parsons Jr., Civil War general and senior executor of his father's estate, was elected president of the board of trustees. Gen. Parsons resigned a short time later in favor of the Rev. Willis G. Craig of Keokuk, who held the office continuously for 33 years.

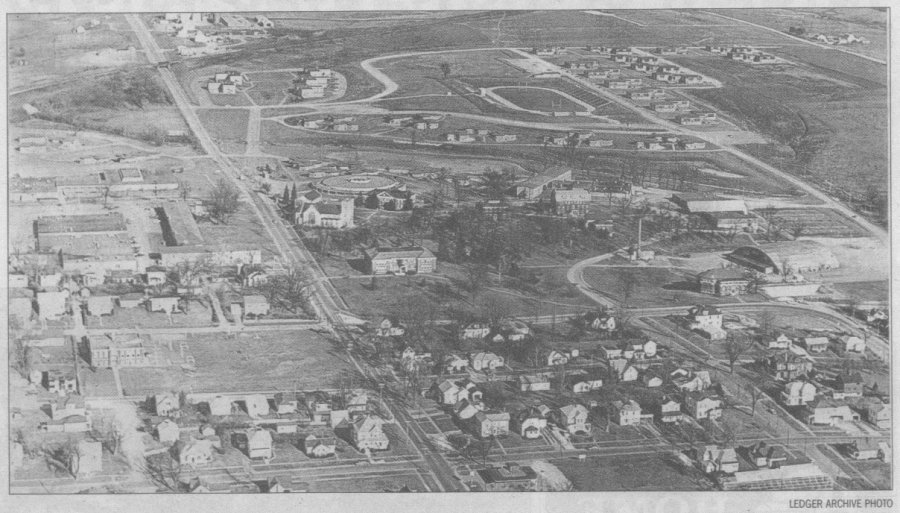

One of the first acts of the board was the purchase of a 20-acre campus at the north edge of Fairfield, including a brick residence built by Bernhard Henn in 1857. Now Ewing Hall, it was known as "The Mansion" when classes opened there on Sept. 8, 1875.

Thirty-four students enrolled on opening day and the figure increased to 43 by the end of the first week. The enrollment for the year was 63. Three Presbyterian ministers, Alexander G. Wilson, Albert McCalla and John Armstrong composed the original faculty.

Wilson headed the faculty with the title of rector. He was also in charge of the college's preparatory department, later called Parsons Adacemy, which remained in existance (sic) until 1917.

Armstrong, named by the board to succeed Wilson in 1877, was the first man to hold the title of president. He died suddenly Aug. 12, 1879 and was the only president buried on the campus.

Fifteen others have held the office of president of the college. The youngest was Daniel E. Jenkins, elected in 1896 at the age of 30.

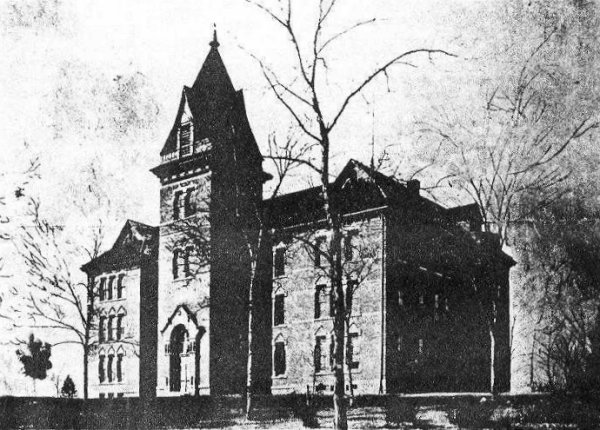

Construction work began on the campus late in 1875 and a new chapel bulding, located west of "The Mansion", was completed in 1876. Two academic wings were added in 1892 and the building was renamed Ankeny Hall. Ballard Hall, the school's first dormitory, was completed in 1902.

The most serious crisis to face the young school came a few months later when Ankeny Hall (above) was destroyed by fire. All records were lost and the college was without classrooms or library.

Hasty alterations were made to Ballard Hall and fall classes opened there in 1902 only one week behind schedule. Financially, however, the picture was dark and the board of trustees considered several proposals to move the college. Mt. Pleasant offered $100,000 and 20 acres of land to re-locate the school in that city.

T. D. Foster of Ottumwa, vice-president of the board, saved the day with a gift of $25,000. Several Fairfield residents also made sizable contributions and the board voted to continue to develop the local campus.

Foster Hall and Fairfield Hall were both completed in 1903 and a new library, supported by a $15,000 gift from Andrew Carnegie, was dedicated in 1907. Trustee gymnasium and Barhydt Chapel followed in 1909 and 1910.

Enrollment at the college grew steadily after World War I, only to decline during the years of World War II. In 1948, Parsons was faced with another serious crisis: loss of accreditation by the North Central Association.

Tom E. Shearer, who became president in 1948, enlisted the support of the citizens of Fairfield in a campaign to strengthen the college plant and program. The effort was successful and Parsons won reaccreditation in 1950.

When Millard Roberts arrived on the Parsons scene in 1955, he brought with him a consuming personal ambition and a flair for making headlines. A native of Schenevus, N.Y., he had been a member of the staff of Brick Presbyterian Church in New York City for three years when he was chosen for the presidency at the age of 37.

Attacking many of education's "sacred cows", he won wide attention with his revolutionary ideas. Few men outside the ranks of politics and show business ever won as much publicity.

His supporters praised his practical, hard-headed approach while his critics accused him of being a promoter and "con man" disguised as an educator.

David Boroff, in his book, "Campus U.S.A.", described him in these words: "Pudgy, flamboyant, tireless, Roberts has the glad-handing manner of a Chamber of Commerce president, the force of a bulldozer, and the guile . . . of a snake-oil salesman."

One of his first acts was to spend $10,000 for his inaguration, a lavish affair held Oct. 29, 1955. Students jokingly termed it "The Ascension."

Roberts' initial objectives were to boost enrollment and expand the college's physical plant. He was imminently successful and for 10 straight years Parsons topped all colleges and universities of the state in percentage of enrollment gain.

After the student body passed the 1,000-mark, new dormitories sprang up almost overnight and new construction continued at a frantic pace almost to the end of his tenure.

In 1958, Roberts was chosen "Man of the Year" by the Fairfield Chamber of Commerce. On Sept. 7 1960, he was presented with a new Cadillac by more than 40 business and professional men.

Roberts established the trimester system at Parsons, making it possible for students to cut their graduating time and enabling the college to make year-round use of its facilities.

Scoffing at the idea that colleges should admit only those students who ranked at the top of their high school classes, Roberts won for Parsons a reputation as America's "second chance" school.

He streamlined the curriculum, increased the student-teacher ratio and dispatched an army of recruiters across the land to bring in students. At that time secondary education was "a seller's market." Students turned away at other colleges saw Parsons as their last hope and they flocked to Fairfield by the hundreds.

By 1964, enrollment had reached 2,500 -- nearly a ten-fold growth in nine years. By 1966, it had doubled again in size.

Roberts built a strong faculty by openly raiding other campuses with offers of fabulous salaries and fringe benefits. Cynics called it the "Gold Rush" and by 1966 the level of faculty salaries at Parsons was the third highest in the nation.

Roberts found champions for most of his ideas, but he aroused the ire of the academic world when he contended that colleges would make a profit by applying the principles of corporate management. In 1966 he was quoted by the Wall Street Journal as saying that Parsons expected to show a profit of $5.3 million that year.

His profits, however, were all on paper. The college's debt grew at an average rate of $100,000 per month during Roberts' 12-year tenure.

Roberts' ability as a salesman caused other communities to clamor for a place on the Parsons "Bandwagon." He once boasted that more than 40 cities asked him to set up new colleges.

Acting as a paid consultant, he helped organize five new colleges at Denison, Iowa; Scottsbluff, Neb.; Albert Lea, Minn.; Beatrice, Neb.; and Artesia, N.M. Two others were planned at Charles City and Council Bluffs but never got past the drawing board. Today four of them are dead and the fifth is leading a tenuous existence.

Roberts' critics accused him of running a one-man show and of playing fast and loose with statistics. These and other charges brought him into conflict with both the Presbyterian Church and the North Central Association. At Roberts' urging, the board of trustees adopted new articles in 1963 severing historic ties with the church.

Roberts' troubles with the North Central Association began in 1962 when six dissident professors issued a formal complaint against the administration of the college. The lengthy document was signed by John C. Moore, Robert W. Stern, John M. Crossett, Walter Hewitson, Elmer Rusco and Ernest Thompson. All resigned or were fired within a year.

Their charges were never made public, but an investigation was conducted by the NCA and the college was placed on probation July 24, 1963.

An NCA evaluation team visited the campus in 1964 and the probation was lifted in 1965 with the stipulation that another evaluation would be made within two years.

Roberts suffered a damaging blow in June, 1966 when Life Magazine published a highly-critical article terming him "The Wizard of Flunk-Out-U." The local Chamber of Commerce reacted by organizing a "Fairfield Fights Back" campaign; thousands of copies of Life were deposited in Central Park and hauled away to the city dump.

A new NCA fact-finding team arrived early in 1967 and on April 6 the agency announced that it had revoked Parsons' accreditation effective June 30. Parsons' academic program was never questioned, but the report cited administrative weaknesses and took Roberts to task for a "credibility gap" in the operation of the college.

Roberts' threat of legal action against the NCA sparked a faculty revolt and by a vote of 101-58, members asked the board of trustees to relieve him of his duties.

Formal ouster action finally came on June 5, 1967 when the board called for his resignation less than four months after granting him a new five-year contract.

Two generations of the Parsons family maintained close ties with Parsons College during the first 66 years of its history.

Three sons of the founder, Lewis B. Parsons Jr., Charles A. Parsons and George Parsons, were executors of their father's estate and members of the board of trustees.

Lewis served on the board from 1875 until his death in 1908, making a bequest of $56,000 to the college. Charles was a member of the board from 1875 until his death in 1905. His gifts to the college, including $80,000 from his estate, totaled more than $140,000.

George Parsons, youngest son of the founder, served on the board from 1907 to 1911. George Parsons' son, Willis, was a board member from 1902 to 1931 and served as president from 1904 to 1913.

Two children of Lewis Parsons Jr. were also trustees. Charles L. Parsons served from 1906 to 1923. Julia M. Parsons was named to the board in 1914, serving until her death in 1941. Both made major gifts to the college to construct the Bible building and cloisters in 1915.

The Bible building has since been renamed Parsons Hall.

Miss Parsons, who made her home at 706 N. Third St., left the major portion of her estate to the college when she died at the age of 86.

Sixteen men held the office of president of Parsons College during its 98-year history.

Alexander G. Wilson was the first administrative head of the college with the title of rector, serving from 1875 to 1877.

Six others served as acting president and three members of the faculty directed the institution as a managerial board for a brief period in the 1920's (sic).

Here is a list of the presidents and the years which they served:

| John Armstrong | 1877 - 1879 |

| Erastus J. Gilett | 1879 - 1880 |

| Thomas D. Ewing | 1880 - 1889 |

| Ambrose C. Smith | 1889 - 1896 |

| Daniel E. Jenkins | 1896 - 1900 |

| Frederick W. Hinitt | 1900 - 1904 |

| Willis E. Parsons | 1904 - 1913 |

| Lowell M. McAfee | 1913 - 1916 |

| R. Ames Montgomery | 1917 - 1922 |

| Howard McDonald | 1922 - 1927 |

| Clarence W. Greene | 1928 - 1938 |

| Donald L. Libbard (sic - Donald L. Hibbard) |

1938 - 1940 |

| Herbert C. Mayer | 1938 - 1940 |

| Tom E. Shearer | 1948 - 1954 |

| Millard G. Roberts | 1955 - 1967 |

| Carl W. Kreisler | 1968 - 1973 |

In 1927-28, the college was headed by an interim managerial board. Its members were Carl G. Guise, Fred D. Mason and Charles Carter.

Horace Gunthorp was the first to hold the title of acting president, serving in 1940. Shearer served in that capacity from 1946 until 1948 and Ralph W. Sayre, a member of the faculty, held the office in 1954-55.

William B. Munson was named acting president in 1967, serving less than two months. He was succeeded by Wayne E. Stamper, who served first as provost and later as acting president in 1967-68.

Everett E. Hadley was named acting president March 12, 1973.

From The Fairfield Ledger

Saturday, June 2, 1973

Parsons College: Died At 98

By Joyce Gabbert

A grand old lady of 98 died Friday; we thought she'd at least live to a 100 (sic) but it didn't happen.

For those of us who saw the handwriting on the wall, her last weeks, days and hours, each became more painful, more agonizing. We just had to give her up.

For someone who believes that death is a part of life, and that there are many things that are eternal, it was easier for me than some. Besides that, I'm an older daughter of '44, not a student-child of '73, or '74 or '75. Nor am I her faculty wife or husband, whose livelihood and professional training have been poured into her collapsing veins.

She gave me a wealth of many things -- a love of God, a reverence for books, a kaleidoscope of drama, an emotion for music, a warmth for people, a concern for truth and a quest for learning. She gave me tremendous friendships during all 33 years.

When she became a paramour of Dr. Roberts we became estranged. She was my stepmother and I never quite accepted her.

In the last few years, I loved her again much more in her battered, tattered state, but like many others I never got quite as close this last time around.

Friday at 11 a.m., I drove to the campus to pay my respects and to talk to her bereaved. It was not an easy assignment.

I began in the Hinkhouse Hall parking lot, moved to the door of Wright Memorial Library and wended my way across campus as far as Carnegie Hall -- the old library to me.

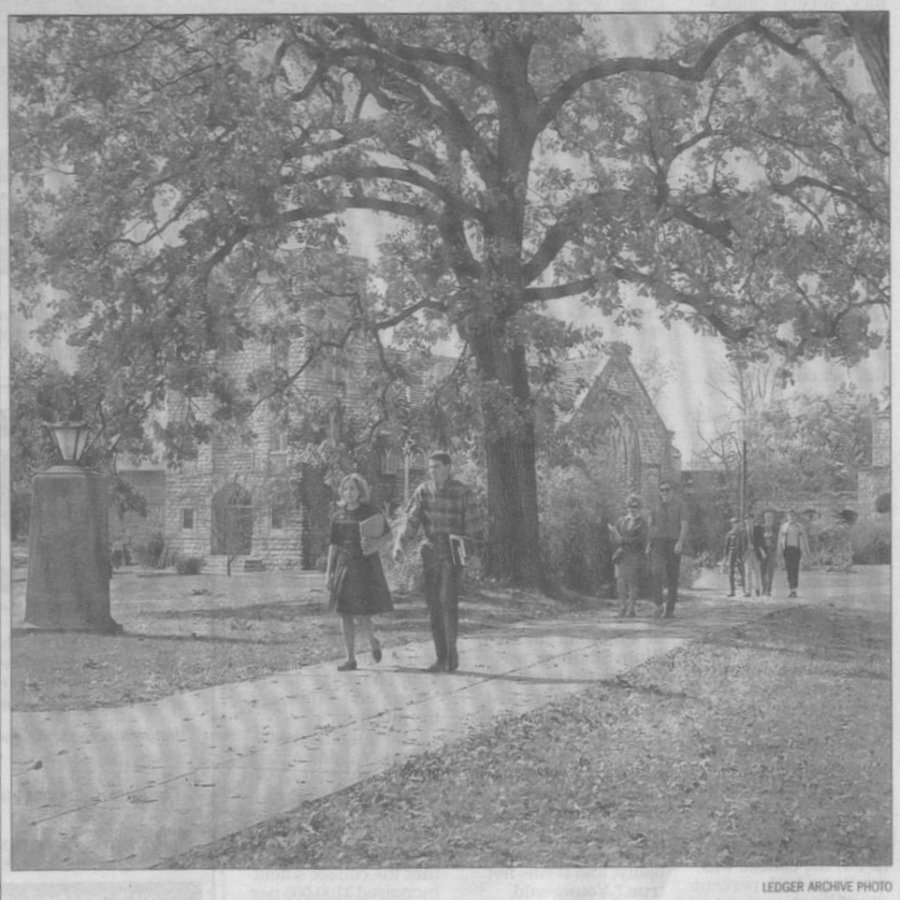

On the new campus I got along fine; when I entered Carter Drive it was a different story. The bright, beautiful June sun, the flood of memories, the hurts and joys of a past accompanied me on my walk.

From The Los Angeles Times

Monday, July 9, 1973

FAIRFIELD, Iowa -- "Parsons College -- The Little School That Refused to Die," the sticker on the window bravely proclaims.

But the 60 modern buildings on the campus are empty. The padlocks, the newly constructed fence and federal bankruptcy signs all give depressing evidence that the college, humming with student activity only a few weeks ago, has collapsed.

"That sticker wasn't very prophetic but it was a good rallying cry," said college administrator Richard L. Wessler, on his way to file for unemployment benefits. He noted, a little sadly, that it was highly unusual for a long established college with 925 students to go bankrupt.

Millard G. Roberts, president of Parsons until 1967, had said he would make the 98-year-old institution "the Harvard of the Midwest" and had sought to do so by paying professors the third highest salaries of any college in the country and building a lavish $25 million campus which now stands deserted.

"If the saga of Parsons College were not attested fact, it would be necessary to invent it . . ." Jaques Barzun, Columbia University professor, wrote in his introduction to "The Parsons College Bubble."

"The story of Parsons is an image, only slightly magnified, of what has overtaken American higher education during the last quarter century and has brought it to a state of moral, financial and administrative bankruptcy."

Barzun wrote while the college was still functioning, but his words ring true after its closure. In part, Parsons fell victim to beliefs that were current elsewhere -- that massive expansion and salesmanship could bring economic happiness to an educational institution.

Seven years ago, Parsons had more than 5,000 students. In the span of a few years, it had become one of the largest institutions in Iowa and had borrowed many millions of dollars to build air-conditioned buildings across fields that had once grown corn.

The apostle of this dramatic change was a hard-promoting, smooth-talking Presbyterian minister, Millard George Roberts of New York, Parsons' president from 1955 to 1967. "Dr. Bob" was what they called Roberts while he was still popular in Fairfield.

Roberts preached the philosophy that a college could be operated at a profit from student income alone, that students deserved more than one chance to succeed in college and that professors should be oriented toward teaching and paid handsomely for the job. He paid some professors annual salaries of $35,000 and himself $75,000.

At first Roberts was praised in this farming and manufacturing town in southeastern Iowa. "He brought lots of students and built lots of buildings and, believe me, in America people believe that bigger is better," said Wessler.

"In colleges, as elsewhere, people are looking for a saviour," said Everett E. Hadley, the college's last acting president. "Why else do they go to cancer quacks? People grasp for straws."

"Roberts is a tremendous man," said Lee Gobble, a college trustee under Roberts, "but he didn't know how to tell the truth, pay bills or when to quit."

By 1967, Roberts had exhausted much of his college's credit in the financial and educational communities. Parsons' academic accreditation was removed by the North Central Assn., partly because of the debts that the college had incurred. Roberts was fired by an angry board of trustees. Later townspeople talked sarcastically about his "edifice complex."

Within a year, enrollment dropped sharply, to 2,000.

The institution regained its accreditation in 1970, but the damage had been done. Enrollment continued to drop. The tenure system made it difficult to dismiss faculty members to cut costs, and Parsons employes had not learned how to live frugally under the Roberts administration.

The college ran out of cash in May. Parsons had mortgaged everything of any possible value -- buildings, equipment and library books (four Iowa banks took possession of the books because of the failure to pay interest or principle on a $565,000 loan.

The college trustees asked for protection of the federal court under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Act.

In his order, the federal bankruptcy judge, Richard Stageman, admitted "the affection and esteem" in which Iowans held the college but said that it was "irretrievably insolvent," and ordered it to post a $250,000 cash bond against the demands of its creditors.

He acknowledged that his order effectively closed the college but argued that "an attempt to operate a college of less than a thousand students has become perilous indeed."

Students, professors and administrators at first rallied to raise the money to meet the bond. But on second thought, the administrators and trustees decided that the publicity of the bankruptcy proceedings, Stageman's chilling judgment, the poor financial condition of the college and the small projected fall enrollment all pointed to one conclusion -- close it now.

And so acting president Hadley went before a student convocation on the last day of school and told stunned, sobbing students that the college was closing immediately because of "insurmountable odds."

In the minds of many persons connected with Parsons, Roberts still is a major villain. "The school went down the drain and Roberts got away free," said one trustee sharply.

When Roberts left Parsons in 1967, the college had a $14 million debt from his grandiose building schemes and salaries and was running on a deficit of almost $100,000 a month.

No one ever accused Roberts of thinking small. He devised the idea of having satellite colleges throughout the country that would be operated under the leadership of Parsons.

Six were formed -- Charles City College in Charles City, Iowa; College of Artesia in Artesia, N.M.; Hiram Scott College in Scottsbluff, Neb.; John J. Pershing College in Beatrice, Neb.; Lea College in Albert Lea, Minn., and Midwestern College in Dennison, Iowa. All of these "daughter" colleges have fallen victim to bankruptcy.

Roberts attracted to Parsons many rich students who had been unsuccessful elsewhere -- "Flunk Out U," some critics termed the school. In his final year, 1967, the college charged students about $2,300 a year in fees, including board and room, slightly higher than most schools of Parsons' class, but it was not enough to make ends meet.

He built many buildings that were never used and he paid some professors far more than necessary to bring them to Parsons.

Roberts had Parsons pay faculty memberships in the local country club. Professors bought luxurious homes in a section of Fairfield now called "the golden ghetto."

His financial extravagance was a major consideration in the institution's loss of accreditation, a publicity blow from which Parsons never recovered.

But if Roberts helped drive Parsons into financial ruin, it should be added that Parsons wasn't too much when he got there in 1955. It had no noticeable endowment, only 357 students and a spotty financial history.

Roberts told trustees and businessmen what they wanted to hear -- that a college could be run like a business at a profit and that they would not have to contribute money to keep his kind of college going.

Roberts made the businessmen feel that they could have their cake -- a money-making, attractive college in their little town -- and never have to pay for it.

"Of course it looks crazy today having a college that big in a small town in Iowa," Roberts said in a telephone interview from his New York City home.

He said that the educators of the country were out to get him and Parsons in the 1960s because he had brought innovative ideas to college education. "Education is a field that is very vindictive. It's like the clergy," explained Roberts, an ordained minister.

Although Roberts has never again been asked to be a college president, he is still in the education business. He said that he was working for the U.S. Office of Education in an urban-rural development program in Scranton, Pa. and spends the rest of his time running a business training school that he owns in Baltimore.

Roberts has no remorse over the closing of his old school. "A small arts college finds it difficult to survive . . ." he said, "and if Parsons was just like the others, why should it survive?"

"The cost is so terrible," said trustee Scott Jordan, "the world is so complicated; these little things like Parsons can't last."

But while small colleges may be less economically feasible, Parsons College, faults and all, will be missed by many of those who came in contact with it. Students wonder if they will get as good an education in the next school in which they enroll. Some are staying in town in the hope that something can be done to reopen Parsons. They could wait a long time.

Students sat around talking on the steps of the administration building several days after the college closed.

"I loved Parsons, even if I was from this town," said Shan Roth. "We had the top professors from all the top schools. We had the greats here, but they were great enough to come to your level."

Like the students, the 57 professors left in the lurch by the closing wonder whether they will ever find a college to suit them again. Most Parsons professors were not great scholars, but many had Ph.D.s from leading universities and appreciated the kind of atmosphere where teaching was rewarded.

"I doubt that I'll ever find a school with as good a relationship between teachers and students as this one," said Harry W. Cannon Jr., the former head of the business administration department. "This relationship has spoiled me for another institution."

Professors not only wonder whether they will find as satisfying an institution but whether they will even find another job in teaching or any comparable profession.

Foster Brenneman, 48, a professor of German and Spanish, has been looking for another job since February. "Everywhere, I'm told I'm too old, that I have too much experience and too much education for the kind of jobs they have to offer," he said.

Cannon is one of the professors who has gone to work. He labors in a local factory as a drill press operator making hog watering troughs at $3.42 an hour.

When asked how that salary compared to what he was making as a professor, he blushed, then laughed and said, "I wish you hadn't asked that." After stopping to calculate, he replied, "It's about 40% of what I was making as a teacher."

Fairfield itself has already suffered much of the economic loss from the college's decline when Parsons dropped in enrollment during the late 1960s. The town's population decreased from 11,587 in 1966 to 8,478 in 1970. Fairfield can absorb the economic impact of the school's closure, but townspeople have started to grieve about the harm that the college's death will do to the social and cultural life of the town.

One woman said she would leave Fairfield. "I'm not going to live in a town without a college. Why, every decent town in Iowa has its own college," she said.

The townspeople wonder what can be done with the college complex at the north edge of town. Some dormitories have never been occupied. The major creditors, including Connecticut Mutual and Connecticut General Life insurance companies, are especially interested in that question.

Some citizens have jokingly suggested that the buildings be used as grain elevators. The only real use that most administrators can see for these abandoned structures is to house another college or school. And, as one asked, "Who's going to start another college in Fairfield, Iowa, now?"

"I didn't always like all those kids riding around on motorcycles and making noise, but, you know, I'll really miss having them around," said a businessman. "This town won't be the same without them."

Another view of Parsons' closing came from William Jellema, an official of the Assn. of America Colleges in Washington, D.C. He said: "The whole of higher education is poorer when one of these pieces is washed off our mainland. The death of Parsons is not something we should take with equanimity."

Those directly affected by the closing -- townspeople, students and professors -- cannot afford the luxury of equanimity.

As a visitor left Prof. Brenneman's house at 11 p.m. recently, the professor came out on his porch and shouted plaintively across his lawn at the departing car, "Please call me if you hear of someone who wants a good German teacher."

Note: The last graduation at Parsons was on June 2, 1973. The campus then stood vacant for two years, with weeds growing tall, until 1975 when the Maharishi International Academy of Santa Barbara, CA, purchased it on September 9th, and sold it the same day to the Maharishi International University. In 1995, the name was changed to Maharishi University of Management ("MUM").

"The Fairfield Ledger and Fairfield Town Crier"

Friday, June 8 & Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Reflections on Parsons College

By Andy Hallman,

Ledger news editor

Maharishi University of Management occupies land on the north side of Fairfield that for 98 years was home to Parsons College.

Parsons College was founded in 1875, enjoyed a meteoric rise in the 1960s, and suffered an unceremonious demise that led to its closure in 1973. Groups such as the Parsons College Alumni Association carry on its memory to the present day.

Two Fairfield residents who remember the college well, through good times and bad, are Bob Tree and Vera Young. Young was a student of the college in the 1940s who went onto (sic) teach there for more than 25 years until it closed. Tree moved to Fairfield from Illinois, and taught at the college for 18 years until it closed. Now they enjoy reminiscing about their days on the north side over meals at SunnyBrook Assisted Living, where they reside.

Young was born in 1924 and raised in Appanoose County. She attended Parsons College, but not right away. Her first stop after high school was Centerville Junior College. Her older sister, Annabelle, had gone to Parsons, so Young and another sister named Virgene matriculated at Parsons together in 1943. Young recalls enjoying her art, history and religion classes in particular.

"You had to take six hours of religion to graduate, and I found it strange that a lot of people did not want to take a religion course," she said. "But once they did, they wanted to take another because we had wonderful teachers."

Tree, born in 1927, grew up in a suburb of Chicago called La Grange Park. He ventured into Iowa to attend Grinnell College as an undergrad, then returned to Illinois for graduate school at Northwestern University.

He heard about Parsons while working on his PhD dissertation in history. He was working at Newberry Library in Chicago when he met a faculty member from Parsons College, who was also doing research for his dissertation.

The man informed him of an upcoming job opening at Parsons. He put in a good word for Tree with the college's administration, and in 1955 Tree packed his bags for Fairfield.

Tree taught American history, Western Civilization, and any other history course he was asked to teach.

Young graduated from Parsons in 1946, whereupon she began teaching at Sigourney High School. However, she was quickly drawn back to Parsons. The college's dean offered her a job as a physical education teacher if she also promised to be a head resident in a girls' dormitory. Young had a background in P.E., having minored in it, and Parsons even offered to give her a scholarship to the University of Iowa where she could earn a master's degree in P.E. during the summer. The offer was too good to refuse.

She also taught health education for a few years, then expanded into other subjects such as anatomy and biology.

In 1948, a year after starting her teaching career at Parsons, Young married coach and fellow faculty member Philip "Tib" Young.

Tree described Parsons as a small, rural college at the time he began teaching.

"It was typical of a number of colleges in Iowa and throughout the Midwest," he said. "The enrollment was fairly small, and consisted mostly of boys and girls from Iowa."

Young described it as a male-dominated college, though Tree said it was not as male-dominated as many people believed. Young said that World War II changed the sex-ratio considerably, when male students were leaving every day in response to the draft.

"When they started coming back, that was a great day," Young said.

A major turning point in Parsons's history was the appointment of Millard G. Roberts to be the president in 1955. Roberts was a Presbyterian minister from New York City, and took the reins of a college that had 357 students. According to a history of the college compiled by former Ledger editor Dean Gabbert, Roberts increased enrollment dramatically, raising it to 5,000 by 1966.

Young and Tree witnessed it all unfold before their eyes. Young said the college simply didn't have enough classrooms and boarding rooms to accommodate so many new students. She recalled beds being placed in Trustee Gym.

"They had to do it to give the students a place to stay," she said. "Dormitories were under construction but weren't finished yet."

Tree said the college had not built many dormitories in the decades before Roberts arrived because students so often rented apartments in town.

"When the students started coming in great numbers, the town couldn't absorb them all because there weren't enough homes," he said.

Young and Tree said that, apart from occasional mischief, the relationship between the students and the rest of the town was cordial.

"One example of that is that townspeople turned out in droves for basketball and football games," Tree said.

"And they came to parties and dances," Young said.

Tree added that many townspeople were themselves graduates of Parsons.

Though Parsons had traditionally received mainly local students through most of its history, Roberts emphasized recruitment from far flung states.

"Here came a lot of kids from New York, Pennsylvania and New England to a different culture," Tree said. "Most of them adjusted well, but occasionally, some had a bit of difficulty."

Young said a number of those students arrived at Parsons because they had flunked out of an eastern school. Tree said the college became known as the "school of second chances."

Young sought to clarify what she believes is a misperception of Parsons College during this period, that because it was a school of second chances meant it must have had low standards.

"By no means did students get through college by doing nothing," she said. "They had to take their old courses over, and a lot of them were very smart. We got a lot of successful graduates. Other colleges began to say that we were giving degrees away, and that was not true."

Tree said he can't recall exact statistics, but he felt the college was sending a high percentage of its alumni onto (sic) graduate school.

"Roberts insisted on having special classes for students who were in trouble," he said.

"There was a lot of help given to them."

As the college sped even faster along, it encountered more bumps in the road. In 1966, a new football stadium, Blum Stadium, was dedicated. However, the year is now most remembered for a Life Magazine article criticizing the college's enrollment practices and referring to Roberts as "The Wizard of Flunk Out U."

"That hurt us very badly, and it was not true," Young said.

Whether the magazine article was fair or not, the school was suffering form genuine financial difficulties. The following year, its accreditation was revoked in part because of its $14 million debt. The board of trustees asked for Roberts's resignation that year after the faculty voted 101-58 to remove him.

"Roberts had a lot of marvelous ideas, but we didn't have the money," Young said. "He spent too much."

"He talked a great game of raising money, but he was really better at spending it," Tree added.

Gabbert's history of the school mentions that the college's debt increased $100,000 per month during Roberts's 12-year tenure as president.

That said, Young feels that the college lost its accreditation not just because of its debt, but also because the presidents of other colleges were jealous of Parsons's success.

Enrollment fell to 2,000 within a year of losing accreditation, and although it was regained the following year, the college never fully recovered. The final season of football was played in 1970. The college closed its doors in 1973 and went into bankruptcy. The faculty received only half their pay that year.

"A lot of students hesitated to come after we lost accreditation," Tree said.

The land became property of the city of Fairfield. It was sold in 1974 to Maharishi International University, which has been here ever since.

Upon Parsons's closure, most faculty and students went their separate ways to seek opportunities elsewhere. But Young and Tree had lived in Fairfield so long, had grown roots so deep, that it was hard to say goodbye. Both of them obtained jobs at Fairfield High School teaching subjects they had taught at Parsons, which meant biology for Young and history for Tree. They recall that Victor Rail was the third Parsons faculty to transfer to FHS after the college closed. They described him as a wonderful math teacher.

Young stayed at the high school 17 years until her retirement. Tree stayed only a few years before moving onto (sic) Iowa Wesleyan College in Mt. Pleasant, where he taught for another 20 years.

Young and Tree have fond memories of the college that lasted nearly a century.

"Most of the students we had over the years liked the experience here," Tree said. "Most of the faculty really enjoyed teaching here, too, and liked having students who might not have been awfully good in high school, but caught fire here and proved to be good. They liked having students discover 'Gosh! Algebra is interesting!'"

Young remembers Parsons as a beautiful campus, designed by the same person who designed Iowa State University's campus.

"It was kept nice even when we were poor," she said.