|

In The Beginning |

|

|

In The Beginning |

|

In these days of comfort and plenty it is difficult to conceive what the life of the early settlers was like, so few their conveniences, so many their trials and hardships. No less strong and high purposes than to acquire land they might call their own and to build homes for themselves, their children, and their children's children, could have carried them through that trying period of struggle and privation. It was a time and place only for brave, resolute hearts and a hardy conquering race.

There were no roads. Indian trails ran here and there, which could be followed on foot and on horseback, but not always with wagons. Travellers came and went at will, but with difficulty, across the open country, often hindered and turned aside from a direct course by natural obstacles. The upland swamps, or "prairie sloughs" as they were called, needed to be avoided and were particularly dangerous in the spring and in rainy seasons. There were no bridges. Streams had to be forded, swum over or crossed on improvised rafts; occasionally the big wagon-box was used for a boat. It was with slow and toilsome progress, relieved it may be by new scenes and adventurous incidents, that the settlers moved into this land of promise.

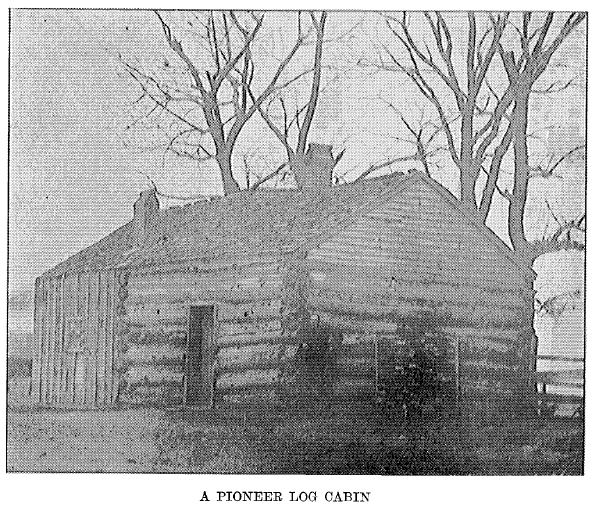

The first task of a settler was to provide a dwelling-place. A cabin of one small room answered for this and cramped as their quarters must often have been it contented him and his family. Fourteen feet square was the common size. It was of simple construction. No nails were used for the good and sufficient reason that none were to be had. Round straight logs with bark on, not too heavy to be lifted by two or three men, were laid up alternately to make the ends and sides of the building. Notches were cut where the ends crossed so that the logs would lie snugly together their entire length. The chinks were filled, then daubed and closed with a mortar of clay. A doorway was left or cut out on one side. The door itself was clapboards pegged to a frame swung on wooden hinges. A peg stuck in an auger-hole fastened it shut. In general there was no window; otherwise it was a mere opening sometimes closed with greased paper. One end of the room, or a large part of it, was taken up by a fireplace, the chimney to which was outside the wall and built up of sticks and clay. The floor was bare earth, or split and dressed puncheons. The roof was strips of bark or clapboards supported by poles extending from gable to gable and held in place by other poles laid upon them.

A settler's outfit contained but little household furniture. With ax and auger all pressing wants in this line were easily and quickly supplied. Stools and benches served to sit upon. A table was but a larger and higher bench. The bedstead was contrived in one corner of the room, the two walls making and end and a side of its frame. Poles laid at right angles from each wall to a forked post of proper height set in the floor for support at a point to give suitable length and breadth, make its other end and side. A few cross pieces completed and fitted it for the bedding. There was no stove. The fireplace furnished light and heat and was the cooking-place. Potatoes were roasted in the ashes; meat was broiled upon a bed of live coals. Corn dodgers were baked in skillets. Mush and hominy were boiled in iron pots swung over the fire on a crane. It was simple cooking. The modern manner doubtless is more convenient and presents more variety, but has not improved upon the savor of the dishes.

Settlers brought with them what flour, bacon and staple provisions they could. It was a limited amount and saved for special occasions. For food they were obliged to depend mainly upon the native fruits and the fish and game they could secure. It was fortunate that in their season strawberries reddened the prairies, that blackberries grew in abundance, that luscious plums hung heavy on the plum-trees in every thicket. Honey was to be had for the cutting of the bee trees. There were fish in all the streams. Deer, turkeys, and prairie-chickens abounded. Ducks during the migratory periods frequented the numerous ponds. But all these things at best provided an uncertain subsistence. Especially was this true in the cold and dreary wintertime when food is most needed.

To meet this want was a serious problem and of deep concern. No sooner did a settler provide a shelter and care for immediate necessities than he prepared and planted, if not too late in the season, a field of corn. His principal implement was an immense plow. It was so big it required three or four yoke of oxen to draw it through the tough sod. It turned over strips of turf three or four inches thick and from eighteen to twenty-four inches wide so they would lie edge to edge in the furrows. The soil it threw up to air, light and warmth was held in the tenacious grasp of compact grass roots. It did not pulverize. The seed was dropped along the edge of every fourth strip or in slits cut with an ax at proper intervals and then pressed together with the foot. There was no attempt at cultivation for that would have encouraged the growth anew of the wild vegetation. The yield was seldom large or of good quality. "Sod corn," as the first crop was termed, was usually cut for fodder and fed to stock. By the end of the season the fibrous texture of the roots was decayed and broken. After a winter's freezing the soil crumbled and was light and friable. It was not uncommon the second season to raise from fifty to one hundred bushels of corn an acre.

Corn was the settler's chief reliance. A little ingenuity overcame the lack of a mill for grinding it. It was converted into meal by grating it, a method, however, which had to be employed before it became dry enough to shell. The grater was a piece of tin or sheetiron punched full of holes and fastened with the rough side out in curved form to a block or board. It was sometimes ground in small quantities in a coffee-mill, certainly a tedious process. The meal was coarse but it served for mush, dodgers, pones and Johnny cakes. Hominy was another dish, wholesome and palatable. It was prepared by boiling shelled corn in weak lye to remove the hulls. This was then washed claen, boiled again to soften and seasoned to suit the taste, after which as needed it was fried and served warm. It was occasionally prepared on hominy-blocks. This was a short log set upright, with its upper end burned out or cut out to make a large bowl. This was filled with corn over which hot water was poured. It was then pounded with a heavy pestle which loosened the hulls and crushed the grains. When washed, it was ready for cooking.

The stock fared better than the human animal. There was grass on the prairies for cattle and horses from the opening of spring till (sic) the falling of snow. Hay was obtained for the cutting and stacking. Hogs thrived on the mast of the timber. Feeding was necessary only during the inclemencies of winter.

There was scant production the first year of settlement west of Skunk River and north of Big Cedar Creek. Tilford succeeded in raising thirteen acres of corn which made twelve bushels per acre. Lambirth, Walker, Huff, the Coops and perhaps some others grew small crops of corn, turnips and potatoes. William G. Coop sowed a few acres to fall wheat, which required another season to ripen. All told there was little food supply produced. Most of the settlers arrived too late in the summer to break the sod, fence it and plant it with any hope of raising anything the year of their coming. For general supplies it was necessary to go to Fort Madison. Few had money with which to make purchases. It is no cause for surprise that some during that winter were reduced to severe straits. The Lemon family is said to have lived for some time on slippery elm bark before their necessities became known to their neighbors. The mother's anxiety for the hungry children caused a partial lapse of reason from which she was months in recovering. When Mrs. Lambirth learned their condition, she gave the sufferers half the breadstuff she had treasured and reserving the other half for her husband that he might have strength to work she herself lived on potatoes. Such was the need; such was the selfdenial. An act like this exemplifies the charity that suffers long and is kind.

There was plenty for the settlers to do to improve their comfort and cheer. There was little opportunity for the pleasures of society. To the nearest neighbor might be several miles. There was no doctor within calling distance. In sickness dependence was placed on household remedies. There were no schools. Children, if taught to read and write and figure, were taught at home. There were no papers to keep them informed on current happenings. Knowledge of important events was brought by chance of wayfarers and carried from house to house. There were no churches. Religious services, however, were not long lacking. The first service was held in the fall of 1836 in the home of James Lanman. The preacher was Samuel Hutton, a Baptist, who came over from Mount Pleasant. He came many more times among the settlers and preached in many homes. It was fiery gospel, including infant damnation, he brought them. Other itinerant ministers visited them and received a cordial welcome. They were esentially a religious people. These meetings were the social centers. All in the vicinity attended them. They came on foot, on horseback, and behind slow oxteams. The women carried their shoes on the way, but wore them during the services. All brought their bits of news and all added their characteristic comments. They compared their experiences and their prospects. By the exhortations of the preachers, by their contact with one another, by the freshness and originality of their ideas, their minds were stimulated, their courage revived and their hopes strengthened.

The jurisdiction of Des Moines County lasted less than a year after settlement began. In this period the first native white child of Jefferson County was born. A doubt has arisen whether this child was William Henry Coop or Cyrus Walker. That precedence rightfully belongs to Coop seems not to admit of question. The thirteenth day of July, 1836, is fixed by the family as the date of his birth. That it occurred in July or early in August is the recorded recollection of John Huff who lived near by. Mrs. Alfred Wright who was present on the occasion agrees with Huff. This distinction was current and accorded to Coop prior to 1857, for in that year it was published as a fact and not contradicted. That Walker was born as late as October is the testimony of Mrs. Sarah A. Lambirth, a relative.

It was on the twenty-ninth day of November, 1836, that "Isaac Blakely and Eleanor Lammon" secured a marriage license from Wm. R. Ross, clerk of Des Moines County, Wisconsin Territory. The wedding took place on the first day of December "at the home of the bride's parents." Far and wide a lively interest was taken in the event. The good housewives who lent their assistance found there were no preserves for the wedding-feast. Considering this deficiency a reproach to their skill, they soon converted some wild crabapples the only fruit available, into the desired sweets to grace the table and the occasion. "William Bradley, M. G." so he signed the official return, solemnized the rites. The validity of the ceremony was later called in question. The Blakelys, to cure the defect, if any really existed, took out the second license to marry issued under the jurisdiction of Jefferson County. It bears the date of March 16, 1839, and runs "for Isaac Blakely of legal age to Miss Elen Landman by consent of parents." The different spellings of the bride's name should be noticed. The next day their second marriage was consummated. "Benjamin F. Chasteen, a minister of the gospel" as he styled himself in the return officiated. The legality of this union was in turn subject to doubt. The difficulty in each instance probably was that neither minister had secured the civil license authorizing him to act in this particular capacity. That Chasteen had not is certain from a subsequent entry made by John A. Pitzer, then clerk of the district court of Jefferson County, Iowa Territory. "This is to certify to all whom it may concern that we a Presbytery of Ministers of the gospel of the separate Baptist order being legally authorized have by and with the consent of the church to which Brother Benjamin F. Chasteen is a member having examined into his Views of the Gospel his qualifications to preach the same do hereby certify that in conformity to the Gospel we have laid our hands on him and legally ordained him to preach and administer the ordinances of the Gospell (sic) agreeable to the separate baptist order in testimony whereof we have set our hands this 7th day November 1839. Thomas Skaggs. Aaron Bleakmore." There was ground for uneasiness for obviously Chasteen had acted without proper legal sanction. So numerous were cases of this kind that in 1842 the Legislature enacted that all marriages previously solemnized by any regularly ordained or licensed minister of the gospel in this territory should be in all respects as valid in law as though solemnized by a minister licensed as required by the statute. The Blakelys afterward removed to Davis County, where Isaac Blakely rose to high esteem and was chosen to represent that county in the House of the Fourteenth General Assembly.

On the seventh day of December, 1836, Henry County was set off from Des Moines County. On February 14th, 1837, Thomas Lambert's was established as an election precinct.

Three weddings occurred under the authority of Henry County in its western settlement. On July 28, 1838, David Smith and Mary Stanly were united in marriage by W. G. Coop, justice of the peace. On November 8, 1838, Frederick Lyon and Rachel Harris were united in marriage by James Gilmer, justice of the peace. On March 10, 1839, at the house of G. W. Patterson, William D. Brown and Martha Patterson were united in marriage by Joel Arrington, minister of the gospel.

On the fifteenth day of October, 1837, the first native white girl was born. She was Mary Francis, the daughter of Thomas and Sarah A. Lambirth.

Death followed slowly in the steps of the pioneers. In the spring of 1837 the dread and unwelcome visitor appeared. With his coming he began the sowing of tears in the new land. The first to die was a child of Alfred Wright. The second to die was David Coop, taken in the fall of the same year in the strength of his maturity. He left in adverse circumstances a wife and two children. John R. Parsons and other handy men of the community split out of logs the boards with which to make his rude coffin. His will was the first to be recorded and probated in Henry County. It was signed with a mark and contained this notable provision: "It is further my will and desire that each of my infant heirs receive a common country education." Henry Rowe died a year later. In his will, it too signed with a mark, occurs a similar expression: "It is my desire that my beloved wife should keep my children together in raising them and that they should have a common English education." What could show the spirit and hopes of these men better than do these solemn instruments?

On the twenty-ninth day of April, A. D., 1837, before Samuel Nelson, justice of the peace in and for Henry County, Wisconsin Territory, personally appeared H. B. Notson, one of the proprietors of the Town of Lockridge, and acknowledged his signature and the signature of W. G. Coop his "pardner" to the plat. The town was laid out on the customary plan. There were twenty-five regular blocks, five in the row. A block was three hundred feet east and west and two hundred seventy-six north and south. The central block was "the square." The streets were sixty-six feet wide; the alleys twelve feet. The alleys ran only east and west. The lots fronting the square on the east and west were fourty-four feet wide and one hundred thirty-two feet deep. The name was descriptive of the site. The Government survey disclosed that its location placed it across the lines dividing townships number seventy-one and number seventy-two north and ranges eight and nine west, and therefore was in four townships. A number of lots were sold, how many is not known. Coop opened a store and put on sale a stock of merchandise which he had obtained in exchange for property in Illinois. Miles Driscoll, Samuel Moore and John Ratliff put up a building and operated a general store. John Huff split out the boards for the shelving. For the small necessities of the growing community Lockridge was a convenient center. Prices were high. Salt was sold at $7.00 a bushel; corn-meal at $1.25 a bushel. Like values were placed on other articles. As economy was a practical virtue of the country and the times, purchases were small.

In the map of the sectional survey of township number seventy-two north, range eight west, made in September, 1837, by E. F. Lucas, there is shown about the center of section one the Village of New Haven. The reference to this section in the field notes names John A. Cochran as a settler, but does not give him or any one as "the proprietor of the town site." This is the only evidence remaining of its existence.

In 1838 Henry Rowe erected a treadmill for grinding corn. Customers put their own animals in the tread and gave a small toll for the use of the mill. Prior to this flour and meal were hauled from Rall's mill in Hancock County, Illinois, a hundred miles distant. To go and return meant a tiresome journey of four weeks or more. Joseph M. Parker served as millboy for the settlement and made the round trip several times.

The number of immigrants soon made desirable and profitable the establishment of ferries over streams where fording was dangerous or impossible. Their proper operation was so important that it was carefully guarded by law. "To keep a ferry" was a licensed occupation. The authority to license and to fix the legal fees was vested in the court of commissioners of the county. The authorized "list of the rate of ferriages" was furnished by the clerk of this court and was posted up at the door of the ferry-house or at some conspicuous and convenient place. The court of Henry County in April, 1837, granted both to Litle Hughes and to James Gibson licenses to operate ferries over Skunk River. The rates fixed were these: Man, 12½ cents; man and horse, 25 cents; wagon and two horses, 75 cents; wagon and yoke of oxen, 75 cents; additional horse or yoke of oxen, 12½ cents, loose cattle, 12½ cents; hogs, sheep, etc., 6¼ cents. Making a crossing at these figures was expensive.

Roads developed in a perfectly natural way. They were products neither of chance nor foresight. They were not commanded. At first travel sought the Indian trails because these ran on the dryest ground and crossed streams at fordable places. Then it found convenient and definite lines between settlements, between settlements and mills, between settlements and trading points. These lines in time were made territorial roads by action of the court of commissioners. The official action was taken largely to secure bridges. The ordinary procedure in establishing a local road was to file a petition and to deposit the fee fixed to apply on the preliminary expense. In Henry County this fee was $5. Three viewers were then appointed by the court. These "blazed the timber and staked the prairies." The pay of a viewer was $1.50 a day.

On the thirteenth day of February, 1837, the court of commissioners of Henry County ordered a road "to commence at Thomas La(m)bert's in the Round Prairie thence to Lewis Watson's mill-seat thence to intersect the Mount Pleasant road at the near edge of the prairie a little north of east of said mill-seat thence the nearest and best route to the county line of Henry county in a direction to Fort Madison." If this description lacks definiteness, let it be remembered that there had been no survey to run lines and to determine points from which to measure distances. Watson's mill-seat was on Big Cedar three miles from its junction with the Skunk. Four days after the order for the road was made, and probably as a result of it, Watson asked the court for leave to build a mill. Leave was granted. Fort Madison was the chief trading point for the settlers of that locality. This road is of particular interest as it was the first to be established by law within the limits of Jefferson County.

There is but brief record in this period of the acts of the court of commissioners in reference to other roads. In May, 1837, John H. Randolph petitioning and J. D. Payne securing the money, David Coop, William B. Lusk and Rodham Bonnifield were appointed viewers of a road "from Lockridge to Gibson's ferry on Skunk River." In March, 1838, it was ordered that a road be viewed "leading from Mt. Pleasant by way of Wamsley's and Ristine's mill to the county line in a direction for Esqr. Gilmore's in the round prairie on the nearest and best route." The viewers were Barnet Ristine, George P. Smith and Jobe C. Sweet. A full year passed before a favorable report was returned and the road opened. In April, 1838, Henry Greer, Roman Bonnifield and Henry Shepherd were appointed viewers of a road "from Rome to Lockridge;" and John Boyer, Scott Walker and John Lee viewers of a road "from Salem to Lockridge and to Mt. Sterling."

Roads to be passable require constant care and maintenance. The duty of oversight and the responsibility for their condition must be chargeable to some authority. To this end road districts were defined and overseers assigned them. Overseers were "required to work all roads and to call on all hands required to work on the roads." The court of commissioners of Henry County in May, 1837, "ordered that the country included in the following limits be and is hereby declared a Road District known as No. 5: to wit, commencing on the south side of Skunk river at the mouth of Big Cedar and up said river to the Indian boundary and with said line south to the county line and with said line east to where it crosses Big Cedar and with said creek to its junction with Skunk river and that Thomas Lambert be and is hereby appointed overseer said district." Although his district comprised several hundred square miles of territory, Lambert could not have found his position onerous for the reason that there were but few miles of road under his supervision.

In April, 1838, the court of commissioners, for convenience and efficiency, made the government township the road district. Township and district bore the same number. Township, number seventy-one north, range eight west (Round Prairie) was District No. 12. John H. Gillam was appointed overseer. Township number seventy-two north, range eight west (Lockridge) was District No. 5. John Parsons was appointed overseer. Township number seventy-three, range eight west (Walnut) was District No. 4. John D. Wood was appointed overseer.

It appears that this symmetrical arrangement of districts for some reason was not altogether satisfactory or was partially impracticable. At the July session of the court, on motion of William Tilford, a road district was defined "on the south by Brush Creek on the north by the county lines on the east by Skunk River on the west by the boundary line," and known as No. 16. Jonathan Turner was appointed overseer.

Among the officials of Henry County were several whose claims were in part soon to be set off in the new county. On March 17, 1838, quoting from the entry, "William Tilford appeared with his certificate of election and was duly sworn in as county commissioner for the term of two years." For the others the clerk was less specific. James Gilmore was qualified on the same date, but for what office is nowhere stated. Inferentially it was for the office of assessor since he was afterward authorized by the commissioners "to assess that part of the county lying south and west of Skunk River." Later Isaac Blakely and Alexander Kirk were also qualified for unnamed positions. John Parsons served as coroner. The panel of the first grand jury which met in October, 1838, include Samuel Scott Walker and Amos Lemmons; of the first petit jury, Daniel Sears and Barnet Ristine.

The opening of the Second Purchase in 1838 attracted many settlers. Before the close of that year there was a large increase in population. A considerable acreage was under cultivation. There was a surplus of corn for which there was no market. There was relief from the pressure of exposure and hunger, but there began to be felt the lack of roads and of schools. These were objects for resident officials to determine rights and apply the law. The election in September of William Green (sic - William Greer) Coop to the Territorial Legislature set in motion the legal machinery to provide the desired local government.

Return to the 1912 History of Jefferson County Contents Page