|

Jefferson County - The Indians |

|

|

Jefferson County - The Indians |

|

What people first dwelt within the bounds of Jefferson County is a mystery locked and sealed by time. On the ridges along the larger streams are mounds in some of which, when opened, were revealed charcoal, pieces of broken pottery, fragments of bones and an occasional stone implement, all bearing mute witness to the presence of a prehistoric race, of whom there is no other visible trace. If there was any connection between the builders of these mounds and the Indians of whom there is record, it was in a remote past. The particular tribes in possession of the country when the whites appeared were late comers.

It is stated that the first settlers found in the western part of the county an iron cross fastened high up on a perpendicular sandstone cliff overlooking Cedar Creek and a wide stretch of lowland opposite. They quarried stone from the accessible face of the cliff until its upper part fell into the stream below. The cross was then removed and carried away. The length of its shaft was three feet, the length of its horizontal bar eighteen inches. The small bar became the property of Judge Charles Negus, who records that he long used it upon his desk as a paper-weight. There was nothing to indicate at what time, or by whose hands, or for what purpose the cross was fixed in that curious location. The most likely supposition makes it the work of some wandering Jesuit, whose adventures and enthusiastic spirit led him to carry the message of his religion into the depths of the wilderness. It stands an isolated fact awaiting an adequate explanation.

It has already been noted that Marquette and Joliet, in 1673, visited the Illinois near the mouth of the Des Moines River. In a message to Congress after the purchase of Louisiana, in 1803, President Jefferson states, "On the River Moingona or Riviere de Moine are the Ajoues, a nation originally from the Missouri." In the period between these two incidents other tribes appeared and disappeared leaving only their names in uncertain tradition and the doubtful tales of travellers.

"Ajoues" is an old way of spelling "Iowas." Although the two forms differ in appearance, they represent the same combination of sounds and take the same pronunciation.

An Italian of distinction, by name Bertrami, in 1823, made a trip up the Mississippi River. Of this trip he published a verbose account. He refers to the River Le Moine as navigable for three hundred miles into the interior and places on its banks "the Yawohas, a strange people who have been almost destroyed by the Sioux." In this same year or a little later their destriction was completed by the Sacs and Foxes who, under their head chief Pashepaho, attacked the principal village of the Iowas without warning. The unsuspecting Iowas were engaged in racing their horses and in other sports and were not prepared to make defence. Notwithstanding the surprise they fought bravely. It was a scene of slaughter. It this battle Black Hawk proved his ability to command and earned his right to chieftainship. The battle-ground was on the Des Moines River bottom a few miles below the present Town of Eldon and near the southwest corner of Jefferson County, across whose prairies the victors had made their stealthy march and on whose wooded bluffs they lay concealed when an unexpected opportunity for a favorable engagement was presented. The Sacs and Foxes held the land until the pioneers came to meet and mingle with them for a brief time and then to crowd them out of it. Their departure was not long to be delayed.

Bertrami thus describes a camp of the Saukis as the Sacs were called. "Their huts are covered with mats or skins. The Canadians call them lodges. They are elliptical. Each generally contains a family; they sleep in a circle upon skins, mats or dried grass. Fire is made in the center; the smoke passes through the round opening in the roof. A copper or tin boiler, which they get from the traders, is supported by a wooden fork stuck in the ground, pieces of wood hollowed into spoons, bits of the bark of trees formed into plates and dishes, the horns of buffaloes cut into cups, constitute their table service. A stake supplies the place of a spit, fingers serve for forks, the earth for a table, a skin on the carpet of nature for a table-cloth. They sit indiscriminately around the food with which Providence and their guns supply them. Neither kings nor courtiers are treated with any distinction. In this perfect republic equality is not less the privilege of animals than men. The dogs, although illegitimate and descended from wolves, are seated at the same table with the savages, and at the same divan; they partake of the same dishes and sleep in the same beds. I have seen young bears treated as part of the community."

"The men and women," Bertrami continues, "daub their faces with red, yellow, white or blue. When in mourning, they paint the whole face black, and even the body, during a year; the second year they paint only one-half; and at last merely streak themselves with it in various patterns. Both men and women wear ornaments on the neck and arms; some wear small glass beads the traders sell them; others, the teeth or claws of wild beasts."

It was the custom of the Indians to assemble and live during the spring and summer under the direct control of a head chief. This gathering together made their permanent village. Near it were grown their fields of beans, melons and corn, if this expression may be properly applied to the little patches of ground they cultivated. The work of planting, tending and harvesting was done by the squaws. Their methods, like their implements, were extremely primitive and crude. Only a fertile soil and a favorable climate assured their crops. At other seasons of the year, the separate families wandered about their favorite hunting grounds, living the true nomadic life, and pitching their rudely constructed wickiups where for the moment fish and game were plenty. In the early spring they made sugar in the groves of hard maples; in the winter they sought the denser woods to secure the protection they afforded against the fury of the elements.

There is no record of any village of the permanent type located within Jefferson County, but there were several such without it at no great distance. A trail connecting a village on the Iowa River with the Iowa Village on the Des Moines River ran a mile west of Fairfield. "A trail," says Henry B. Mitchell, "never crossed a swamp or stream, except where there was a hard bottom."

Three companies of Untied States Dragoons marched, in 1853, from Camp Des Moines, which was located on the Mississippi River, along the divide between the Skunk and Des Moines rivers as far north as Lake Albert Lea. Their route both going and returning took them across the southwestern part of Jefferson County. An unknown dragoon kept a journal of the expedition. On their return, on Saturday, the fifteenth day of August, he writes, "This day we came twenty miles passed Opponuse or Iway town. This village is situated on the right bank of the Des moines on a handsome Prairie & for an Indian town is very handsome and appears to be increasing in wealth and population." South Ottumwa occupies the site of this village. The next day the dragoon recorded further, "Crossed the Des Moines & encamped near Keokirks Village I have been much pleased with the neatness & apparent comfort of these Indians & the more I become acquainted with their mode of life the better the opinion I form of them They are the most decent in their manner of living of any Indians I have seen."

It was near "Keokirks Village" that General Joseph M. Street, in 1838, as a central and convenient point located the Agency of the Sacs and Foxes, now the town of Agency in Wapello County. Here of necessity chiefs, braves and untitled tribesmen, all visited. It was but a few miles east to Jefferson County across which led the direct route to Burlington, the seat of the territorial government. Without doubt their parties frequently traversed the county as they passed to and from the Agency, from one village to another and to the settlements near the border. It is equally certain that they established temporary camps beside its streams. William H. Sullivan recalls that in his boyhood days there was a camp of this character on Cedar Creek near Smith's Ford. E. F. Lucas, who surveyed in 1837 what is now Walnut Township in his field notes mentions as near the southeast corner of section twenty-three "a beautiful sugar camp, interspersed with may wigwams where the Indians from an appearance have made quantities of sugar." Many of the first settlers must have met Keokuk, Appanoose, Wapello, Hard Fish and Poweshiek; and to few of them indeed could the sight of Indians following the trail in their own peculiar fasion, that is, in single file after the leader, have been either uncommon or strange.

In the fall of 1837, at the instance of the Government, a party of the leading Sacs and Foxes were taken east by General Street. It is related that at Washington, Pennsylvania, a number of these Indians were in a stage-coach going down a steep hill. There was no brake on the coach, for the brake was not yet invented. Frequently a driver, disliking the annoyance and delay of stopping to fasten and unfasten the chain which was used to lock a rear wheel so that it would drag and not turn, would trust to his skill, the weight of his horses and the strength of the harness, to make a descent in safety. Such trust the driver displayed on this occasion. The result did not confirm the excellence of his judgment. He tried to cramp the wheels, when he discovered the danger. The effort came too late. The coach upset, throwing driver and passengers to the ground. "This breaks the treaty," one of them exclaimed as he scrambled to his feet. "This breaks the treaty." The speaker was Black Hawk. An eyewitness of the accident was Joseph Alison McKemey a young man, who not long after came West and making a home in Jefferson County largely aided its development.

Black Hawk was a notable man. He was a sturdy fighter, the kind of fighter beloved of a virile world. The consequences of his illfated war he accepted with outward stoicism. Contrary to the custom prevailing among Indian chiefs of his rank and influence, he had but one wife. His last years were spent on the banks of the Des Moines River near the scene of his greatest victory. He died in the autumn of 1838 and was buried as he requested to be, where he sat in the council with the Iowas after their defeat. The turbulence and exceitment of his life did not earn him repose after death. His body was stolen and taken first to St. Louis and then to Illinois. It was recovered by Governor Lucas and in 1840 brought to Burlington. It was the intention of his family to carry the body with them to the reservation set apart for the tribe in Kansas, but before the time arrived for their departure it was consumed by a fire which destroyed the building containing it.

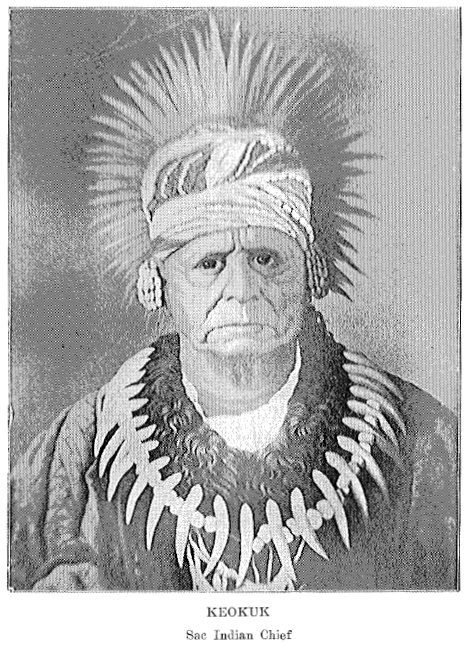

From the beginning of his activities in tribal affairs Keokuk, the Watchful Fox, was Black Hawk's rival for supremacy in the councils of their nation. These two were the central figures about whom the Sacs and Foxes divided in the contest with the whites who were seeking an opportunity to enter upon their lands. Events moved rapidly in Keokuk's interest. Believing the war with the whites futile and fatal to his people, he strongly advocated peace. His immediate followers were preparing their warpaint when he boldly offered to lead them on the single condition that they would first put to death their women and children. This appeal convinced them of the desperate nature of Black Hawk's proposals and was effective. They submitted to Keokuk's authority and took no part in the conflict. In the negotiations which followed the defeat and destruction of Black Hawk's forces, the Government, recognizing the ability, and friendly disposition of Keokuk, lent him the weight of its influence. This strenghtened and assured his position among his people. "Keokuk, or he who has been everywhere," was the first Indian name signed to the treaty of peace. This agreement opened Iowa to settlement.

Keokuk's appearance is described as imposing, his manner as graceful and dignified. At all times he wore a necklace of bear's claws which was his only ornament. He was fond of ceremony and display and used them with great effect in accomplishing his purposes. On formal visits to other chiefs he was attended by his several wives and a number of favorite braves. He was eloquent, quick of wit and shrewd at a bargain. Hard Fish, who led the opposition to him after Black Hawk's death, accused him of dishonesty in distributing the funds received from the Government. On account of this charge it was proposed to pay the money yet due direct to the heads of families. This intention coming to the ear of Keokuk, he visited Governor Lucas at Burlington and objected to the plan. "I have some of my braves with me," he said, "and they want all their money paid to the chief as before, and not scattered like the fallen leaves of the trees in autumn." To his credit it must be said that the change in the manner of payment had been incited by irresponsible traders. He shared the failings common on the frontier to white men and red. He had a passion for fast horses and gambling; and he drank whisky to excess. He died in Kansas in 1848 from poisoning.

When the Territorial Legislature of 1843 established eleven new counties, it named eight of them in honor of Indians well known to its members either personally or by reputation. These Indians were Black Hawk, Keokuk, Appanoose, Wapello, Kishekosh, Powesheik, Tama, and Mahaska. This deliberate action by lawmakers of an alien race proves they were possessed of qualities to be admired and emulated and shows how high they were held in public esteem. It ought to be remembered, when their faults are reviewed, that distinction of this kind is not bought and sold, and is not bestowed where there are no virtues.

It is true that the personal habits of the Indians were not pleasing to their more fastidious neighbors. They had little apathy to dirt and were not choice in the selection and preparation of their food. They kept both dogs and skunks in numbers about them, esteeming the meat of these animals a delicacy. In respect to property they were scrupulously honest. They prized corn but would not take an overlooked ear from a field that had been husked without first getting permission from the owner. They were styled beggars because like children they freely asked for anything that struck their fancy. Mrs. John W. Sullivan, the wife of the first treasurer of Jefferson County, one day had just taken some fresh cornbread from the Dutch oven, when two Indians chanced to stop at the house. She gave each of them a portion. They liked it so well that to her surprise they returned the next day with a large company and a sack of meal and requested her to bake them some cornbread like her own. They meant no imposition and were at fault only in their ignorance of the niceties of a social life more complex than their own.

The relations of the Indians with the settlers of Jefferson County were always friendly. No act on the part of one called for retaliation on the part of the other. In large measure this condition was due to the careful oversight, prudence and personal influence of General Street and Major Beech, who succeeded him as agent. The Indians found these officers of the Government worthy of trust and willingly accepted and acted upon their wise counsels. For General Street in particular they had a warm affection. On his death in 1840 they asked that he be buried in their country; and when they sold their lands they reserved for Mrs. Street the section on which his grave is located. These acts evidence their respect and love. Near this man who was his best friend, Wapello, who died on the fifteenth day of March, 1842, was buried at his express desire. Side by side they are taking their long last sleep.

On the eleventh day of October, 1842, at Agency City, John Chambers, governor of the Territory of Iowa, concluded a treaty with the Sacs and Foxes by which they ceded to the United States forever all the lands west of the Mississippi River to which they held any title or claim, or in which they had any interest whatever. This acquisition was popularly termed the New Purchase. In anticipation of its opening settlers thronged along the border. At midnight of the thirtieth day of April, 1843, the barrier of soldiers which had prevented their advance was removed. When the hour struck the impatient watchers to the noise of guns and by the light of flaming bonfires, on foot, on horseback, and in such vehicles as they could command, pushed westward to found new homes. When the dawn broke, Jefferson County had ceased to be the frontier. The Indians were gone.

Return to the 1912 History of Jefferson County Contents Page