Cerro Gordo County Iowa

Part of the IaGenWeb Project

|

The Globe Gazette

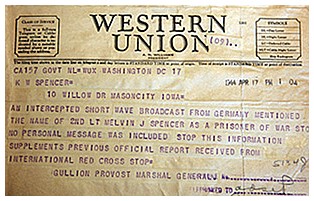

Lt. Melvin Spencer Was at Stalag Luft 1; Soon to Be Here, He Said

The cable came directly from Melvin and the letter from a friend of the family, T/Sgt. Bill LYONS, formerly of Clear Lake, who was in the group that took Melvin from the camp to Paris. "My thoughts are with you," Melvin cabled. "Hope to see you soon. All well and safe." The letter from T/Sgt. LYONS stated that Melvin was in very good condition and "judging from the looks of the snapshots he enclosed, he really is," reported the SPENCERS. He had been a prisoner since Feb., 1944. Others from the community known to have been at this camp are Lt. Donald G. HARRER, Mason City, and Flight Officer Roy B. MARTIN, Clear Lake.

The Globe Gazette

Had Had Hard Luck Getting Back, and Was 18 Days on Boat Second Lt. Melvin SPENCER, who was liberated from Stalag Luft 1 at Barth, Germany, on May 1, after some delay in getting to the states, has arrived here for a 60-day leave. He is visiting his parents, Mr. and Mrs. K. W. SPENCER, 1322 President N. W. His brother, Dennis, employed by the FBI at Washington, D. C., is also here for a visit. Lt. SPENCER reported that he had some hard luck getting back, being bunched up in camp before leaving Europe, and on top of that was 18 days on board ship enroute to the states. He reached Newport News, Va., on July 1, just 2 months after he was released from the prison camp. SPENCER was captured when the crew was forced to bail out of their plane after being hit by a fighter plane. They had dived the plane from a height of 22,000 feet to a cloud layer at 500 feet and were starting back when they were hit. Two of the enlisted men were killed and 2 were injured, he reported. They were taken prisoners by the Volksturm and some civilians, then taken to an interrogation center before being sent to the camp. Lt. SPENCER often saw F/O Roy MARTIN of Clear Lake, who was in the same compound and barracks, but saw no other Mason Cityans, though he knew they were in the camp. Things here seemed no different, said SPENCER, though he was surprised at the seeming "plentiness" of food in the midwest - he had heard so much about rationing and food shortage and was prepared for something different. When Melvin arrived in the states he had visited with his brother, Dennis, in Virginia. Dennis, now here, arranged for a vacation from his duties, and arrived a week after Melvin's arrival. Lt. SPENCER will report to Miami Beach, Fla., at the end of his leave.

The Oklahoman

Hostilities ended in World War II 67 years ago today when the Japanese surrendered on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay Story by Matt Petterson, Staff Writer At 9,000 feet over Germany, with his B-17 in trouble, two crew members dead and two more wounded, 95th Bomber Group navigator Melvin SPENCER bailed out. From the roar of engines and machine gun fire, he fell into dead calm. "The first sensation was one of total silence and peace," SPENCER said. "It was the total opposite of what you've just been through on the plane." Combat operations in World War II ended 67 years ago today when the Japanese formally surrendered on the deck of the USS Missouri. More than 16 million Americans served during the war. Though their numbers continue to decline, those still living have stories about where they were and what they were doing when the war ended. The morning of his last mission was frantic for SPENCER. He had been transferred to another bomber crew after its navigator was sent to the lead plane for the mission that day. In the early morning rush to get briefed and down a quick breakfast, SPENCER left his flying jacket folded on his bunk. After bailing out, SPENCER made it safely to the ground but was picked up by the Germans. He was taken to Frankfurt for interrogation. "They spoke perfect English," SPENCER said of the Germans. "They weren't really that hostile. They were more trying to be your friend or buddy."

After three days in solitary confinement, SPENCER was transferred to Stalag Luft 1, a large prison camp for Allied aviators in Barth, Germany. The Mason City, Iowa, native spent about 14 months in the camp, where life wasn't as easy as it was portrayed on the popular U.S. TV show "Hogan's Heroes" a couple of decades later. "The myth of being able to have good food and in-and-out escapes, none of that stuff happened," he said. "According to the camp commandant, there were over 100 tunnels dug in the compound. There were many attempts, but they were never successful."

"At first, we would get a huge vat of thin German soup with some potatoes in it and some German bread that was about 40 percent sawdust and leaves. It was solid like a rock, but later it tasted pretty good."

SPENCER had settled in to life at Stalag Luft 1. Prisoners had plenty of time on their hands, he said. Card games were popular. Cigarettes were as valuable as gold, as were the occasional Red Cross packages the prisoners received. "There was a group of musicians that formed a band," he said. "There was also a group of POWs that formed a group that called themselves the Table Top Thespians. The stage was a group of tables from the mess hall." There were few comforts from home, but SPENCER was able to communicate through letters. He received a photo of his two sisters and a cousin that he put in a makeshift frame made from a bed slat. He stained the frame with shoe polish and hung it over his bunk. "It not only gave me a lift, but others in the room enjoyed it immensely," he said. Some prisoners were able to procure a radio. Its parts where kept hidden at different locations around camp and assembled whenever they wanted to listen to it. News heard on BBC broadcasts made its way into a camp newspaper. Just a handful of copies were passed around under the noses of the guards. "The soldiers running the camp weren't SS (German elite troops), which was fortunate," SPENCER said. "They were mostly respectful in their treatment of us. There were no atrocities. At one point, Hitler had tried to issue and order that all the Jews be segregated, but our people refused and the Luftwaffe never enforced it." As the war wound down, conditions worsened. Food was scarce. The soup had been replaced by more sawdust bread, and on some days, nothing at all. As the Red Army closed in on the camp, the commandant was ordered to move it. Allied officers in the camp protested, fearing they would be shot by their own planes. "The German commandant said, ‘If you don't want to leave, I'll turn the camp over to you and we'll leave,' " he said. On May 1, 1945, SPENCER woke up to find the Germans gone. American prisoners had taken over the guard posts. There was a roll call that morning, and an announcement was made that all of the prisoners should stay in the camp because it was too dangerous to leave. "That lasted for about two days until the Russians got in there and tore down the fences and burned the guard towers down," he said. "A bunch of prisoners walked away, and some of them were killed in the uncertainty of the situation." After four missions as a navigator in a B-17 and 14 months in a prison camp, the war was over for SPENCER. He returned home on an LST, a ship designed to transfer tanks. With just a 5-foot draft, the seas in the Atlantic were rough. "I was seasick for 20 days," he said. When he arrived home at midnight in Mason City, his family was waiting for him. "We had a mini-midnight celebration, and then I enjoyed a long night's sleep in my own bed," he said.

Melvin SPENCER spent 14 months in a German prisoner of war camp after being captured in 1944. About 9,000 American and British prisoners were held at Stalag Luft 1 in Barth, Germany, during the war. Most prisoners were serving in the U.S. Army Air Corps or the Royal Air Force. Here's a look at some aspects of life inside the prison.

One of the staples for prisoners was Black Bread Broat, which was about as appetizing as it sounds. The bread was made from 50 percent bruised rye grain, 20 percent sliced sugar beets, 20 percent sawdust and 10 percent minced leaves or straw. SPENCER said it was common to find pieces of glass or sand in the bread.

Billed as the only honest newspaper in Germany, the POW WOW (Waiting on Winning) was published from Stalag Luft 1 by prisoners who were urged to read the publication quickly and in groups of three. Copies were distributed to seven prison camps inside Germany. Few remain today because readers were urged to destroy their copies when finished reading to avoid detection by guards who knew about the paper but were unsuccessful in stopping its publication. News came from a variety of sources, including loud speaker announcements, incoming soldiers and by using a radio that SPENCER said was disassembled with its parts hidden after being used. The paper was typewritten and duplicated with carbon paper. When there was no carbon paper, new stocks were made by smoking sheets of paper over oil lamps. The Pow Wow was edited by Ray Parker who went on to become a reporter for the Los Angeles Examiner and Los Angeles Times. SOURCE: Melvin Spencer, merkki.com

But, although SPENCER had left the war behind him many years before, a part of his past would entice him to make a trip back to Europe. After SPENCER was shot down over Germany, another flyer had taken the jacket SPENCER had left on his bunk. And, the flyer wore it for the remainder of the war. To SPENCER, the jacket was lost — until 1995, when he learned the other flyer had donated it in the early 1980s to a museum in the United Kingdom. The jacket was eventually displayed at the Red Feather Club Museum in Horham. Both SPENCER and his son, Dennis, and grandson, Nathan, traveled to England where the veteran was reunited with the jacket he had left behind on that hectic February morning 68 years previously. "What can you say when you put on a jacket," SPENCER said laughing. "It was a jacket, and I put it on. It wasn't anything magic. I didn't have any particular attachment to it. It just happened to be mine." When looking back at what he lived through, SPENCER said the war taught him a lot about himself and life. "It was a great learning experience," he said. "I learned to value my country, my freedom and our Christian heritage. I was proud to serve in the military and have never regretted for an instant my service." Transcriptions by Sharon R. Becker, May of 2013

|

Return to Cerro Gordo County Honor Roll

Return to Military Index Page Return to Cerro Gordo Home Page