Our Neighbors in the Services.

Emmetsburg, Iowa – Roy E. Johnston, 46, superintendent of schools of Palo Alto County, was assigned as a first lieutenant to the artillery officer’s antiaircraft replacement pool, at Camp Wallace, Texas, on April 21. When he was inducted it made Palo Alto County’s first father and son combination in active service. Bruce Johnston, 21, a senior at Simpson College, enlisted last year in the air corps and now is a flying cadet at East Lansing, Mich. Lieut. Johnston is a veteran of the First World War, in which he served 13 months as an enlisted man before receiving his commission in the field artillery. He served 12 months as an officer.

Source: The Sioux City Journal, April 27, 1943

![]()

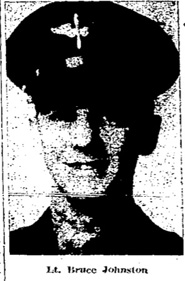

Lt. Bruce Johnston Tells of Life in Nazi Prison Camps

LIBERATED

Second Lt. Bruce Johnston, son of Mr. and Mrs. Roy Johnston of Emmetsburg, arrived Monday from the east coast following his liberation from an Axis prisoner of war camp in Europe. The well known 23 year old flier expects to spend the next couple of months here before being reassigned to duty. Bruce looks to be in excellent condition in spite of some 3 ½ months spent as a prisoner of the enemy, but he was released on April 29 and has had the intervening period to regain some weight and strength.

Bruce was a caller in the Reporter office on Tuesday and related the story of his capture and imprisonment. As a bombardier on a B-24 Liberator, he was engaged on his 18th mission from an Italian base. Although the crew had been through several rougher missions as far as flak and anti-aircraft fire went, this was apparently the trip that had their number on it. While on the bombing run over Yugoslavia, one engine was knocked out by flak. The target was to have been Vienna, but the crew jettisoned the bomb load and attempted to follow the squadron. Another heavy flak concentration followed and accounted for two of the remaining engines.

The fourth engine merely served to keep the craft under control while fast losing altitude. The pilot gave the signal to abandon ship. There were twelve men aboard. Lt. Johnston being one of four commissioned officers. When the signal was given, he first toured the ship to check up on the full crew to make sure they had received the signal. The men were all assembled for their jumps. Bruce’s regular chute had been tossed into a corner of the plane at the takeoff and had accidentally sprung open. He was forced to grab one of two emergency chutes and was rather skeptical of its condition, but, as he described his first bail-out, “it was something like going swimming in icy water. I figured I might as well go and get it over with.” He dropped through the opened bomb bay doors and pulled the rip cord. “And I really pulled it,” he related.

Floating down, he heard considerable machine gun fire below and realized that the Nazi patrol forces were attempting to knock off the dropping crew. However, none were hit. After landing, he planned to hide out. He discovered two young children from an adjacent village and discovered they were Yugoslavs. They led him to their home where their parents seemed to welcome him and called him “comrade.” By this time a sergeant of the crew joined him. They were given beds for the night, after many of the townspeople had called to see them. They all seemed friendly, and the fliers thought themselves in luck. The next morning, however, they were promptly taken to the Gestapo in the village. They were questioned, but revealed only their names, rank and serial number. Most of the questions were personal rather than of a military nature, but the captives stuck by their refusal to answer anything further. The Gestapo threatened to turn them over to the civilian police for hanging as murderers, but to no avail. They were then marched about three miles through the snow, without shoes, to a warehouse-prison building. Bruce wondered if this was it—that they were to be shot, but aside from the cold and badly frostbitten feet, they were unharmed.

They were taken eventually to Nuremberg where they were kept from February 4 to April 1st in unheated buildings. The winter climate was about like Iowa’s and the cold and lack of any sanitary facilities did not add up too much comfort. Rations contained of thin barley soup, flavor badly, one loaf of black bread per week, and occasional small potatoes. Later some Red Cross food was received to supplement the starvation diet, but the men were becoming too weak to be interested in any activity of recreation, even if it had been available. Lt. Johnston went down in weight from 137 to 112 at the time of his liberation.

On April 1st the group was transferred to Moosburg prison from which they were liberated on April 29 by advancing American troops. As the troops approached, the prisoners could follow the course of the battle from the grounds. The guards also kept them advised of the nearness of the liberating troops, and when the Americans crossed the river near the prison camp, the prison guards formed orderly lines and calmly marched out and surrendered.

Bruce frankly admits to being a party to some bribing and blackmail during his incarceration. The prisoners had managed to obtain two radios in the camp, neither in working order. It was believed that one was repairable if a tube could be obtained. The trap was set, and when one of the “goon” guards, as the flier put it, walked into the American’s room, one of the prisoners was unwrapping a delicious chocolate bay, worth $40 in the camp market. They guard eyed it longingly, and to his surprise was offered it, but with the explanation that he would have to give a written receipt for it, which he did gladly. He was then promptly notified that if he did not immediately secure them the needed radio tube, they would turn in the receipt to his captain as evidence that he was accepting bribes from the prisoners. The tube was immediately obtained and installed, but it was found that one last tube was needed before the set would work.

This posed a problem, but the ingenious Americans met it also. The camp officers were certain that some radio equipment was being assembled somewhere in the camp, and offered a 2 week furlough to any guard who would find it. The Americans promptly heard of this and another “goon” guard was propositioned. If he would get them the last tube required, they would lead him to the radio, and he would get the furlough. The tube was again obtained, and he was given the extra radio set which could not be repaired, and which he promptly turned in for his furlough. The tube was installed in the original set, and the prisoners listened to allied broadcasts from then on, following the course of the war without difficulty.

Lt. Johnston saw no atrocities or ill treatment of prisoners, aside from the Gestapo threats and the first difficult march under them. Aside from the intense hunger and uncomfortable living conditions generally, they did not suffer physically.

On the trip home from Boston, Bruce met Cpl. Fred Beschorner of Emmetsburg, lately liberated, and the two discovered that they were held prisoners in Nuremberg camp at the same time without being aware of the other’s presence.

He does not know what assignment will be awaiting him next, but in the meantime his target for today and every day while home is going to be his mother’s cooking.

Source: Emmetsburg Reporter, May 31, 1945 (photo included)

![]()

Bruce Gordon Johnston was born July 7, 1921 to Roy Earl and Grace Wolfgang Johnston. He died Oct. 31, 1998 and is buried in Resthaven Cemetery, West Des Moines, Iowa.

Source: ancestry.com

![]()