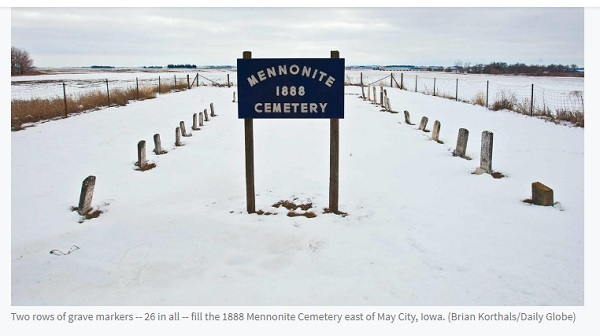

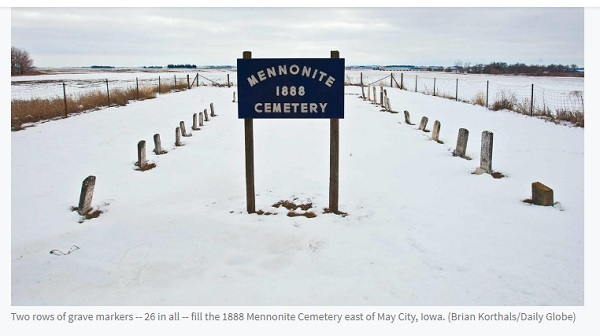

Two rows of grave markers -- 26 in all -- fill the 1888 Mennonite Cemetery east of May City, Iowa.

MAY CITY, Iowa -- Standing at the entrance to the 1888 Mennonite Cemetery near the intersection of two Iowa crossroads, a visitor can see for miles in all directions. There's a smattering of farms, groves of trees and acres upon acres of farmland.

Some might say this little cemetery is in the middle of nowhere -- just as the Mennonites who settled in this area of Osceola County in the 1880s had wanted it to be.

The story of the Mennonite Cemetery near the intersect of A-34 and M-18 really can't be told without sharing the story of the Mennonite Colony that inhabited this area of southeast Osceola County from 1887 to 1915. The McCallum Museum in Sibley has several articles and photos that help shed light on this group of people.

As Ezra Martin shares in his memoirs, "Mennonite Settlement, 1887-1915," the story of the Osceola County Mennonites begins in Canada in the fall of 1884. It was then that Bishop David Stauffer ordained Jesse Bauman to lead a new Mennonite Church.

"The newly formed church became interested in settling elsewhere," Martin writes in his book, excerpts of which were republished in the May City Memoirs Centennial Newspaper of 1989 and available for viewing in the museum.

Fellow Canadian Fritz Moyer, who was connected with a real estate firm, learned that land was available in Iowa, and a group of men searched it out to discover a vast open prairie without trees and without buildings just east of the Ocheyedan River.

"The first year was long and lonely for the new settlers," detailed the May City Memoirs. "They wrote letters home and encouraged others to come. Those who remained in Canada promised to join them the following year."

In March 1888, approximately 50 people, about three-fourths of them children, made their way from Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, to northwest Iowa by freight cars. The families, referred to only by the patriarchs, were Josiah Martin, Elias Gingrich, Jacob Brubacker, Amos Bauman, Owen Bauman, Abram Reist and Henry Groff.

Within weeks of their arrival in Osceola County, the Mennonites were hit by a measles epidemic. By the time the sickness had run its course, five children were dead. They included Jesse Bauman, age 3; Rachel Gingrich, age 2, Elizabeth Stauffer, age 11 months, Amos Gingrich, age 4, and Anna Wideman, age 1.

"A cemetery was started and graves dug before the newcomers had houses to live in," the Memoirs read. "Children were buried in one row in order of death and the adults in another row in order of death."

This was a bit unusual for Mennonites, whose kin are customarily buried in family plots.

There are 26 graves in the 1888 Mennonite Cemetery, each marked with a simple white headstone carved from limestone. Though many of the stones are now barely legible -- weathered by age and the elements -- they were carved in either English or German lettering.

"They could have purchased cheaper land near Hartley, but they wanted to settle as far away from a town as possible," wrote Helen Lorch for the Osceola County Centennial Edition of the Sibley Gazette in 1972.

Bauman, the colony's bishop, was the first to have his home and barn completed, setting the style for other Mennonite homes and barns yet to be built by colony members, according to a story published by the Sioux City (Iowa) Journal on Jan. 3, 1971, and referencing another book, "The Mennonites in Iowa," published by the Iowa State Historical Society in 1939.

The buildings were supposed to be painted red and uniform in shape with hip roofs, small windows and no cornices. This would prove to be a sticking point, however, with some of the colony's members. These were the first disagreements among the group, and soon escalated to other issues regarding Mennonite standards of simplicity and uniformity. They couldn't agree on the use of spring wagons, electricity and which modern conveniences to permit. They even argued about shaving.

Meanwhile, the "Business Corners" as developed by the Mennonites grew to include a grocery store, jewelry store, broom factory, watch repair shop, harness shop and wagon shop. A church, painted in the traditional red of the colony's houses and barns, stood east of the cemetery.

In Martin's Mennonite Settlement memoirs, he tells of how the Mennonites raised milking shorthorns, hogs and colts, and grew oats, flax, corn and hay.

"Some families had as many as six or eight children, born at home without the help of a doctor," Martin wrote. "Doctors were few and far apart. One of the women served as mid-wife for many families."

Bauman, who owned the best land, had financial success in Osceola County, according to "The Mennonites in Iowa." That success led to progressive action, like purchasing electric lights, a milking machine and a telephone at each of his three farms. He also had a gasoline tractor and a threshing machine -- none of which were favored by the Mennonite families in Pennsylvania.

"In time, nearly all of his church members turned against him, including his brother," the article states. The church dissolved in 1911, and the families started to leave northwest Iowa.

"Between 1911 and 1915, nearly all the families left -- some to Canada, others to Michigan, but the majority to Lancaster and Lebanon counties in Pennsylvania, where the first Mennonites settled in 1683 to escape persecution in Europe," the Journal article reads.

Martin was the last baby born at the Mennonite settlement before the exodus. His family moved back to Pennsylvania, where he remained and wrote his book about the Osceola County colony.

The newspaper clippings and book excerpts telling the story of the Osceola County Mennonites are archived at the McCallum Museum in Sibley, Iowa.

A group of Mennonites from Pennsylvania journeyed to Osceola County each year to tend to the graves, but since 1968, Ralph and Lois Wichmann have tended to the cemetery.

The Wichmanns live directly across the road from the cemetery, and at age 85, Ralph still goes out and puts fertilizer and insecticide on the grass in the spring to make sure the sacred place doesn't become overgrown with dandelions.

Lois is now in the nursing home in Hartley, and Ralph visits her every day for lunch. Come spring, he will begin his second caretaker duties again -- keeping the grass mowed and the cemetery looking neat and clean for visitors.

"It's just one of them things," Ralph said. "I grew up by it."

Ralph's grandfather purchased the homestead from the Mennonites, and his parents moved to the farm in 1924. Over the years, the family became good friends with the descendants of the Mennonite settlers.

"We've visited them in Pennsylvania and twice in Missouri," Ralph said. "They're real nice."

"They don't have cars yet, they're still horse and buggy," he said of the Old Order and New Order Mennonites who have visited with him while stopping at the cemetery.

He has often been asked by the visitors if there were ever any photographs taken of the Mennonite Church that once stood next to the cemetery, but as far as he knows, there weren't. Certainly, the Mennonites didn't use things like cameras.

Ralph remembers where the church stood, though. The foundation was still visible up until 1951, when road crews came in and dug it out to pave the way for new county roads.

The Wichmanns were asked to be caretakers of the cemetery in 1968 by Harvey Donnenworth, whose wife attended school with the Mennonite children.

The first Mennonite colony in America was formed at Germantown, Pa., in 1683.

Used with permission from Julie Buntjer, The Globe, Worthington, Mn. June 29, 2020