On a cold winter day in early February, 1859, abolitionist John Brown entered Tabor with twelve people,

he and his men had liberated from slavery in Missouri, during raids on December 20-21, 1858. The

journey to Tabor was long and difficult. After escaping west to Osawatomie, Kansas, the group had

traveled over 200 miles north enduring bitterly cold temperatures, snow drifts, swollen streams clogged

with ice, and the constant threat posed from attack or arrest by bounty hunters, federal marshals and at

times, the U.S. Army.

On a cold winter day in early February, 1859, abolitionist John Brown entered Tabor with twelve people,

he and his men had liberated from slavery in Missouri, during raids on December 20-21, 1858. The

journey to Tabor was long and difficult. After escaping west to Osawatomie, Kansas, the group had

traveled over 200 miles north enduring bitterly cold temperatures, snow drifts, swollen streams clogged

with ice, and the constant threat posed from attack or arrest by bounty hunters, federal marshals and at

times, the U.S. Army.

News of Brown’s Missouri raid had spread quickly sparking a furious response

from pro-slavery forces throughout the area. He was a wanted man with a price on his head, including

$3,000 offered by the state of Missouri. One of Brown’s men recalled that there were “squads of armed

and organized parties [on their trail] to either kill, arrest, or otherwise retard our advance.” But once in

Tabor, Brown knew he was safe, he had been in town before and saw the village as a refuge and an

important stop on Iowa’s Underground Railroad.

The most precious traveler in Brown’s group, and certainly the youngest, was a two-week-old baby who

had been born on the journey. The newborn’s parents, Jim and Narcissa Daniels, along with two small

children, had been taken by Brown from their owner, Harvey Hicklan. Daniels was anxious to escape his

captivity because he believed he and his family were slated for the auction block and would be “sold

south,” a common practice among slaveholders living near free states, like Iowa. At the time of their

escape Narcissa was pregnant at full-term and would shortly give birth in a log cabin where Brown’s

group had found refuge near Garnett, Kansas. A healthy boy was delivered under the supervision of Dr.

James G. Blount, an abolitionist who had fought with Free State militias and Brown in Kansas. But even

with a newborn in hand, the group could not delay their departure. On January 20, they left the relative

comfort of their shelter and set off north through Kansas Territory. The caravan headed toward Nebraska

Territory, passing near Lawrence, Lecompton, and Topeka. They found shelter and supplies from friends

along the way, including a night spent at an Otoe settlement located south of the Greater (Big) Nemaha

River. Pressing on, Brown and his charges passed through Nebraska City and crossed the Missouri River

to Iowa and into the care of Ira Blanchard. Living in an area known as Civil Bend, “Doc” Blanchard was

a well-known figure in the Underground Railroad who worked closely with friends in Tabor, where

Brown and his caravan arrived February 5.

Tabor was a small settlement of around 15 families, some living in simple log cabins and structures built

from mud brick. The settlement’s spiritual leader, Congregationalist minister John Todd, was an ardent

opponent of human slavery. He railed against the institution from the pulpit on a regular basis and never

minced words. Typical was his sermon National Judgment Deserved where he said, “God delivered us

from British oppression and instead of freeing the slaves, which according to the principles upon which

our fathers based their right to freedom, were equally entitled to liberty, we still held them in

bondage—thus our fathers took to their bosom the chilled viper.” Todd reflected the town’s commitment

to help freedom seekers in any way possible. In 1856, he and his wife Martha stored a cache of Brown’s

weapons and ammunition in their home.

The people of Tabor welcomed the runaways and gave them

shelter in their schoolhouse, providing bedding, a woodstove and food. Brown’s men were lodged in

several homes while he stayed with town founders George and Maria Gaston.

After almost a week in Tabor, Brown was ready to move on, but Narcissa Daniels had fallen ill and was

not able to travel. The town fathers were worried about separating the mother and child from the main

group and were concerned that knowledge of Brown and his charges might already have spread, attracting

the attention of bounty hunters. The danger posed from pursuers was ever present—the Fugitive Slave

Act of 1850 required the apprehension of all runaways and arrest of those assisting in their escape.

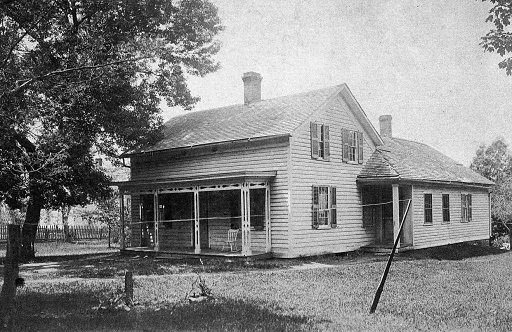

English-born James and Mary Vincent, residents of Tabor since 1855, were ready to help.

The couple

were active in the Underground Railroad and James was a member of Tabor’s military company,

organized in 1856, as a precaution against the fighting in Kansas spreading to southwest Iowa. He and

Mary stepped forward and volunteered to care for the mother and her baby in their home, giving her time

to regain her strength. Brown’s caravan left town on February 11 and after a few days of rest, Narcissa

and her baby were reunited with the main body near Atlantic, Iowa.

Brown’s train of canvas covered wagons pushed east across Iowa and accepted help along the way from a

variety of supporters, including newspaper editor John Teesdale, who donated the cost of the ferry across

the Des Moines River. The group was also enthusiastically welcomed in Grinnell, spending two days

being hosted by town founder Josiah Grinnell and fellow Congregationalists with food, clothing, and

shelter. Never missing a chance to expound on the merits of his crusade Brown spoke to the Grinnell

congregation at a Sunday service, reminding attendees that “slavery is a crime [requiring] a wall of fire

around it.” When Brown’s group pulled out, Mrs. Daniels remained ill and Grinnell noticed her baby was

being held in Brown’s arms as he sat on the wagon’s front seat.

The runaways arrived in West Liberty, Iowa on March 10 and were placed in a railroad freight car,

secured though a $50.00 fee paid to an agreeable railway agent. Although they had traveled hundreds of

miles the group remained one step ahead of pursuers—in Davenport a U.S. marshal searched the train’s

passenger coaches but fortunately, didn’t go into the freight cars. The train arrived in Chicago and

received further assistance from other abolitionists, including Alan Pinkerton, a man remembered today

for founding a nationally known detective agency. Another train ride took the party to Detroit where they

sailed to freedom across the Detroit River on March 12 to Windsor, located in what was known at the

time as Upper Canada.

Estimates put the number of runaway slaves taking refuge in Canada at around 20,000 and the majority

remained there making new lives, including Jim Daniels and his family. Canadian census records suggest

their baby, born on the long trek from Missouri, grew to adulthood in the Windsor area. Although too

young to have remembered the dangerous journey his family made and the notable personalities who

helped him attain his freedom, the young man would have been easily reminded of the adventure by his

very name, conferred by his parents at the time of his birth: John Brown Daniels.

Source: Contributed by Harry Wilkins