|

|

|

|

|

||

| Cherokee

County Families

|

|---|

|

Memories and Stories |  |

| Richard D. Cleaves From My Past: Cherokee, Iowa to New York City 1909 to 1933 |

| 31.

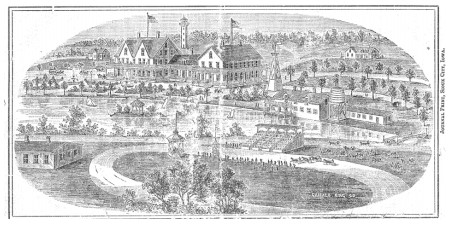

Chautauqua, Donkey Ball, Circus, and Big Bands In those days, of course, we didn't have television. As a matter fact we didn't really have radio and I don't think we had a radio at our house at that time. Our diversion, our entertainment was in things that came in -- like Chautauqua. Chautauqua

Functions at Magnolia Park, Cherokee

Another thing that came to town was the donkey ball.

These fellows had donkeys and they would go around the grounds and choose up two teams. What you had to do was this -- you stood up and they pitched to you and you hit a ball. Then you jumped on your donkey and tried to get him to first base. Well, they had the donkey trained, so that one particular donkey instead of going to first base would go to third, and another donkey would go halfway to first base and he would stop, and so forth. I played in the donkey ball but I never got the donkey to get to first base. Another thing they had was to bring in the carnivals. I think I was maybe a sophomore in college. This carnival had a boxer and if you could stay three rounds with him, you got a dollar a round. Everybody egged me on. I had so-called boxing lessons when I was in Geneva -- you know, three steps forward each time, you put out your left hand and then your back off three steps and so forth. I went in and I stayed the three rounds and got my $3. The owner of the show came up to me and he said, “This guy we have is no good. I think you're much better. Don't you want to join our carnival and be our boxing representative?”

When the circus came in, the thing was to go down and watch them unload and then try to get a job at the circus where the kids could get a free pass. We would go down and they would unload the elephants and they’d have a parade through town. I can't remember how old we were, but Prent and I went down to the circus grounds to try to earn our passes. Our job was to set up chairs. We and a bunch of other young kids set up all the chairs. When it came time to get our passes, we walked up and Prent got his and the other kids got theirs. I came up about the end of the line and the guy looked at me and he said “You’re too small. You couldn’t have done any work you so you can’t have a pass.” I was quite upset about this, so I didn't go home. I just hung around the circus all that afternoon. Finally, my dad appeared and just took me by the ear and marched me back home, about 15 or 20 blocks. Not only I didn't see the circus but I was also punished. It was really very unfair. Cherokee had a nine-hole golf course and once a year they would have a tournament where everybody would get a certain number of strokes -- 57 or whatever it was with their handicaps. The players would carry a wooden shingle. The Cherokee golf course opened in 1916.

When a player got to the end of the number of strokes, he was supposed to write a poem on the shingle and stick it in the ground where his ball stopped. Afterwards they had a dinner party, where the poems and phrases written on the shingles were read. Also, a prize was given out for the best poem and for the player who had won the golf tournament. I remember my dad's poem. It read like this (which they would have really liked) -- “Here I stand broken hearted. Tried to drive and only farted.” One Fourth of July when we were very young, we almost burned up our mother. We were out in the backyard, just little kids with sparklers and so forth. Dad felt that we could handle roman candles, which you just hold in your hand and they shoot up. He explained what we were supposed to do.

My mother was wearing a gossamer summer dress. Dad lit the roman candles. We were so excited we turned around and said, “Mother, look what we're doing!” We shot these roman candles at her and her dress caught on fire. Fortunately, she was not burned and Dad put it out before anything serious happened. 32. Lutheran Churches When I was working for Guy Gillette, one of my jobs when I got home was to do campaigning for him before he was up for re-election. I went up to Le Mars and went with the Swedish County Democratic chairman. We were going out to a little town that was having some kind of a fair. As he drove through the country, he had a Saturday Evening Post up on the steering wheel and he read all the way. It was really very frightening. We come in over the hills --- there are a lot of hills in northwest Iowa, very beautiful country -- and looked down into this little tiny town. You could see two great big church steeples just across the street from each other. To make conversation, I said, “You have two beautiful churches there for such a small town.” He said, “Oh, yeah.” I said, “Well what's the one on the left-hand side of the street.” He said -- “Dats a Luterin church.” I said, “Well, what's the one on the right-hand side of the street.” He said, “Oh, Dats a Luterin church.” I said, “There two big churches, and they’re both Lutheran churches. What’s the difference?” He said, “On the left-hand side, they think that Eve gave Adam the apple and made him sin…But on the right-hand side, they say that son of a bitch ought to die!” ***************** I hope I've given you some idea of what it was like to live in and grow up and Cherokee Iowa, a small town that time with less than 5,000 people, with the right side of the tracks and the wrong side of the tracks. Fortunately, with Dad in his position, even though we didn't have really all of the luxuries, we did very well. Cleaves

Home in Cherokee, Iowa – 730 West Main Street

33. Stowaway from Puerto Rico to New York [Editor’s note: In March 1933, Dick had come to Puerto Rico from Martinique and was out of cash. He needed to be in Washington, DC by March 11 to begin his job with Congressman Guy Gillette. While the story does not take place in Cherokee, it does relate to Guy Gillette and reveals more of Dick Cleaves’ personality, formed while a youngster in Cherokee.] When President Roosevelt closed the banks in the spring of 1933, it caught me in Puerto Rico. Actually, the bank closing didn’t make much difference to me, as I happened to have my complete assets, amounting to $4.35, in my pocket. What was of immediate concern was the cablegram that had just arrived. REPORT WASHINGTON MARCH ELEVEN. It meant that I had a job with the new Administration, my first since I had gotten out of college. The problem was getting to the job. How I happened to be in Puerto Rico right at that time can be explained by saying that I had come up from Martinique as a workaway on a small inter-island tanker. That was a month previous. My plan was to get another workaway to New York, but I hadn’t been able to swing it. Every time a boat came in, I would go down to the dock where she was berthed, and try to find the mate. First, I had to dodge the dock captain. The few times I was able to get to the mate, the answer was always the same. “I can’t give you a workaway. You have to get clearance from the office.” So, I would go to the office. There I would be told that they had nothing to do with it, and that I would have to see the mate. By the time that point was cleared up, the boat had loaded and sailed. As I said, this had been going on for a month. I didn’t mind too much, until the cablegram came, as the weather was pleasant and I had succeeded in living within my means. My cot in a flophouse set me back 15 cents a night, and I spaced my two dishes of rice and beans each day so that I was never terribly hungry, just always rather hungry. A dish of rice and beans cost 6 cents. The morning after I got the cablegram, I discussed the problem with a fellow in the same flophouse where I was living, who had the cot next to mine. He had been second mate on a freighter that had dropped cargo at San Juan on her way to the West Indies and the northern coast of South America. He had gotten drunk on shore leave, missed his ship, and was now on the beach. “You look like a smart kid,” he said, “so you ought to know by now that things are bad in the States, and you can’t get a workaway to New York. Why don’t you stowaway?” I said, “Stowaway, I don’t know. How do you stowaway?” While he’d never done it, he said. “You just stow away. Find yourself a spot in the boiler room, or maybe you can slip into a lifeboat. You have to figure it out yourself. Why don’t you try the Coamo? The cruise liner Coamo is in port today and is sailing tomorrow. Why don’t you go down tomorrow and stowaway?” I said – “Well, I’ll see what I can do.” The first thing I had to do was to arrange for my suitcase to be sent to my uncle’s in New York. My friend said he would take care of it for me, so I gave him enough money for charges and wrote out the address for him. That was the last time I ever saw my suitcase. The next day I shined my shoes, wore a knicker suit, slung a camera over my shoulder and walked down to the dock where the Coamo was tied up. Looking at her from a distance didn’t give me any ideas about how to start stowing away. There seemed to be a lot of stewards and passengers milling about on the decks, and I couldn’t see much chance of finding an unwatched lifeboat. I walked up to the visitors’ gangplank for a better look.

I walked up the visitors’ gangplank and there was a question of -- you know -- where I was going to hide till the ship left? She was a beautiful ship, and the going-away atmosphere was very exciting. I could see that everyone was looking forward to a gala trip. However, I had to find myself a hiding place as it was then 12:30, and the boat was due to sail at 1:00. My first thought was that I go to the men’s toilet in one of the corridors. I walked down to the men's toilet and just as I went in, I looked at the end of the corridor and there was a steward watching me. I came out again and I looked at other corridors and for other places and there was just no place to hide. I just walked into the First Class Lounge, and I bought a copy of the Saturday Evening Post and I sat down and started to read, very nervous of course. The ship was about an hour late in sailing so every once a while a steward would come through and he would say “All Visitors Ashore... All Visitors Ashore.” And I’d sit there, and tell myself I better get off this tub. But I’ve got to get up to New York and Washington. Pretty soon again he comes through and says, “All Visitors Ashore,” looking right at me. But I just sat there. Finally, they cast off the lines and the Coamo left the dock. After we had passed Morro Castle and were out of the harbor, I went out on deck. I wanted to see when they dropped the pilot because I knew that after they dropped the pilot that they couldn't take me back to San Juan. There was a young couple sitting there with another young girl, very pretty girl from Ohio. As I was walking by them, a steward came up to me, asking “Would you like a chair?” I said, “Yes I would” and he put the chair up next to these people. I started to talk to them and found out that the young couple were on their honeymoon. They had come down on the same Coamo and were on the way back to New York. They had met the girl when they got on the ship. Tea was served very soon, as we had been so late getting away. After a good game of shuffleboard, which the girl from Ohio and I had won, I turned to the young husband and said, “I might just as well tell you. I’m a stowaway.” He said, “What are you going to do?” I didn’t have the slightest idea. “Well,” he said, “I suppose you could sleep in a deck chair, which wouldn’t be bad for the first couple of nights, and probably between morning broth, afternoon tea and what we could sneak from the table, we could keep you fed. But I don't know how you're going to get through Immigration and Customs when you get to New York.” Then he added, “. “Why don’t you give yourself up and offer to work. They can’t throw you off now, and maybe they will make it easy for you. When we came down on the Coamo I got to know the Purser very well and he's a real nice guy. So why don't you go down and give yourself up to the Purser and then after that I'll go down and talk and see what I can do.” I said fine and sat around a while longer, was feeling good with the sun shining on deck and with nice people. It was a wrench to leave, but the deck steward had asked me a couple of times for my name and stateroom number so he could put them on my chair, so I thought I had better get at it. I walked down to the Purser’s office and the Assistant Purser was there behind the cage and said, “Yes, Sir. What can I do for you?” I said, “Well, Sir, I’m a stowaway.” “What?!” His face looked as though he were seeing the Devil. “I’m a stowaway, Sir,” I repeated. He looked around quickly. “Come back here before anyone sees you,” he ordered. I stepped into his office. The first thing he told me was that I has wasting my time stowing away, as when the ship got to New York I would be kept in the brig, and then bought back to Puerto Rico. He asked if I had any papers. I replied that I had a regular tourist’s passport. He looked it over very carefully, and then said, “Well, don’t say anything about this, but they might let you off. Don’t say I said so. I better call the bridge.” He got on the horn and he said, “Let me speak with Bridge Mate.” (I could hear both sides of the conversation. In fact, I could have heard the other end even if there had been no telephone.) The Bridge Mate got on, and the Assistant Purser said, “Sir, I’ve got a stowaway down here.” “WHAT? You’ve got a stowaway? Keep him there until I can send someone down for him.” Soon the quartermaster came down --- a very strict young fellow who didn’t crack a smile, who said “Come with me.” So, we went up to the bridge and saw the Mate. The Mate looked 70 years old and was a Norwegian – I think his name was Bergson or Bergman. He seemed to me to be the biggest man I had had ever seen. He stood about six feet five inches, and must have weighed, muscle and bone, about 280 pounds. He stood over me, and called me, and all my confederates, every name he could think of. He said, “So you're the stowaway. How did you get on the ship? Who helped you on the ship?” I said that nobody, sir. He said “Don't lie to me. It had to be a steward. Did a steward help you? You can't get on the ship without help. How did you do it?” I used ‘sir’ in every answer. I said. “No, Sir, no one helped me.” He tried another tack. “Where were you hiding? In one of the cabins? Or maybe in a locker?” “I was in the First Class Lounge,” I replied. His jaw fell. He turned to the Quartermaster, who was standing by the wheel. “I’ll be an S.O.B.,” he said. “I never heard of a stowaway like this before.” Turning back to me, “Well, do you want to work, or shall I throw you in the brig? If you want to work, I'll let you work where you can be out on deck.” I said – “Well, sir. I've been trying to get to get a workaway for a month now and so I'd like to work.” He said “fine” and asked if I had any work clothes, and I said “No, Sir, I don't have any work clothes.” So, he turned to one of the fellows on the bridge and said, “Take him down to the slop chest and find him some work clothes that will fit him.” Down at the slop chest, the fellow pawed around, but all that he could find was a Quartermaster’s uniform. I put that on, and it fit me pretty well. By then it was time to eat. You know that you don’t eat all at the same time. So while they’re taking me down to the crew’s dining, the other part of the crew was just going on watch and coming up on deck. This one fellow stopped me and put his hand on my chest and said “I’ve been on this doggone tugboat for five years. Last week I made Able Body Seaman AB. You come on the first day and you're a goddamn quartermaster!” I slept in the crew hospital. Every morning I'd report to the bridge and every morning I would wash the bridge or chip paint or rust or something. I guess it was about the second day when I reported the Mate said “Where do you eat” and I said I'm eating in the crew's mess and he said “Eat in the officers’’ mess; it’s a better mess.” And it was! There you could have a steak for breakfast or chops or all of the food that they had in first class except they didn’t fool around with olives and sardines and the fancy relishes. I did enjoy having steak or lamp chops for breakfast as a welcome change from rice and beans. The next day was Sunday so I reported in, and the Bridge Mate said “Today is Sunday. Don’t you know what day this is? We don’t work on Sunday.” I'd been given instructions not to talk any of the passengers but when I was working, this young man on the honeymoon came along and talked to me and said “How are you doing?” I told him and he said here are some cigarettes and said I looked very smart in the uniform. He kept an eye on me all the way up to New York. We got into quarantine about 5 in the morning and the passengers were to debark at 8:30 that morning. I was in the crew hospital and didn't have a clue. When we left quarantine and steamed up the river at end of the bay, I was quite excited and I put on my good suit. I decided to open the door, get out on deck, go to the can, and look around. Except that I didn’t open the door. It was stuck. I worked at it for a moment, then went over to the porthole which looked out on deck. Some of the dining room stewards were going by, so I called to one and said, “I don’t know what’s wrong with this door; I can’t seem to get it open.” He said Ok, walked around, disappeared from sight, and came around with eyes as big as saucers. “Boy,” he exclaimed, “there’s the biggest padlock I ever saw in my life on that door!” I said “Ok – but let someone know that I have to go to the can.” One of the crew members came and let me out and then took me back to the crew hospital and locked the door. We were warped into the dock and tied up a little after eight-thirty. At about 9 a.m., one of the stewards came and he said “Oh my God, I forgot all about you. You haven’t had anything to eat. I'll bring you some breakfast – what do you want?” “Ham and eggs or something.” Pretty soon the dock captain came on and he looks through the porthole and said, “So you’re the stowaway.” “Yes, Sir.” He said, “You’re out of luck, Mac. They’re going to ship you back to Puerto Rico.” I waited I would say until about noon. One of the stewards came down and said they want to see me up in the First Class dining room. So I went up there. There were two immigration officers. One was a normal officer, a very nice-looking older guy, and the other one was a young immigration officer, probably been on the job for just a week. Then there was a representative from the New York and Puerto Rico Steamship Company. The old guy set me aside while they were having their lunch and after examining my passport said, “As far as we're concerned, you’re clear. You can get off.” He called to the officer from the Puerto Rico Line and said, “As far as we’re concerned, he can get off.” The company officer said, “I’ve got to make a telephone call.” And he came back and said there was nobody there to give authorization. They continued their lunch. This young immigration officer said to the older guy “I wouldn't let him off. Obviously, he could find some money someplace to pay for his passage. I just wouldn’t let him off. I’d send him back to Puerto Rico.” But the older guy said, “Nah, I think he’s telling the truth (because I had told him about my job with Guy Gillette in Washington) and I don’t see any reason not to let him go on.” After they had finished eating and arguing about me, the company representative disappeared. In a little while he came back and said, “I’m going to let you off, but don’t ever get on one of our ships again.” I said, “No Sir, I won’t!” I shook hands all around and did not fail to compliment the company on the wonderful service that their line afforded. I was quite excited naturally as I walked down the gang plank. At the bottom, whom should I see but my friend, the one who was on his honeymoon. This was about 1 in the afternoon and they had gotten off at 8:30. He said, “So they’ve let you get off the ship,” and I said yes. I said I want to thank you for everything you did…you know, cigarettes and support. He said, “What are you going to do now” and I said “Well, I'm going to go out and call my uncle and get to my uncle's. He’s sure to be there and he’ll have some money for me.” He said “Fine.” I shook hands and left and went out and made the telephone call and caught a crosstown bus. And I was halfway to my uncle’s apartment somewhere on 77th street and it suddenly hit me. The young husband had waited around for over four hours to be sure that I got off the ship all right. And I didn’t even know his name. By then there was no possibility of knowing it, taking them to dinner or reciprocating in some other way. …………I've always regretted that. Steamship

Coamo

[Editor’s note: The passenger ship Coamo was completed in 1925. Dick was fortunate not to be on the ship on December 2, 1942, when it was sunk by a torpedo from German U-604 with the loss of all 186 on board. Source: https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/ship/2486.html ] 34. Obituaries for Dr. Prentiss Bowden Cleaves (1879-1951)

Click an obituary to see an enlarged version

35. Guy Gillette, Dr. Prentiss Cleaves and Dick Cleaves Guy Gillette is known as Cherokee County’s most prominent citizen in the 20th century. Born in 1879, he was a soldier, a lawyer, farmer, congressman, senator, and a United States leader in international affairs. Guy and Prentiss were contemporaries in Cherokee and became lifelong friends, and Dick and Prent knew Guy from childhood. After Dick returned from Martinique and Puerto Rico in 1933, he became Guy’s congressional secretary until Guy launched his senatorial career in 1936. Aside from helping the Democrat Guy in his campaign, Dick and his friend Whip Walser promoted the reelection of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 by projecting slogans on New York skyscrapers. The Gillette Park and the historical designation of the Gillette home in Cherokee acknowledge the contributions that Guy Gillette made to Iowa in agriculture; to the United States in opposing McCarthyism and supporting equal rights for women; and internationally for promoting international trade and the creation of Israel as a joint Jewish-Palestinian state. Aside from creating the opportunity for Dick to “drop his name” in getting released from detention in New York (after stowing away on the Coamo from Puerto Rico), the Editors believe that Guy probably assisted Dick to join the US-UK Trade Delegation to Brazil in 1945 and the Department of Commerce Trade Mission Japan where the family lived from 1948 to 1951 -- and where co-editor Richard P. Cleaves was born. Preceded in 1956 by the death of his wife Rose Freeman Gillette, Guy passed away in 1973 at 94 years old.

Dick Cleaves and friend Whip Walser Promote Roosevelt’s Re-Election in 1936  36. Eulogy to Richard Delaplane Cleaves (1909-1994) [Editor’s note: Dick was born in Cherokee, Iowa on March 27, 1909. Margaret Grant Shurtleff Cleaves (Margo) was born on September 17, 1915 in Peoria, Illinois. Dick and Margo were married on March 1, 1941. Dick and Margo’s other two children were Perri Allerton Rifenburgh (1941-1967) and Susan Hill McCarthy (1947-2005). Margo passed away on December 18, 1993, when she and Dick were living in South Pasadena, Florida. Dick Cleaves passed away in Louisville, Kentucky on August 7, 1994, while living with son Richard Prentiss Cleaves. Below is the tribute written by Richard and Peter for Dick’s memorial service on October 29, 1994.] Dick Cleaves, our father, had a spirit of adventure. He dreamed of safaris and boat trips down the Amazon, and he realized many of his dreams. He was the first bicyclist to peddle down the Pan American Highway to Mexico City. He lived on a Caribbean beach (a beach comber, according to Mom) and was a physical education teacher at a private girl’s school in France. He worked with General MacArthur in Japan, and retired to Spain where he and Mom loved to see the sun set of Gibraltar every night over drinks. Peter will always treasure memories of a photo safari to Kenya when Dick was approaching 80, and his thrill at tracking the jaguar and floating on a hot air balloon above the Serengeti Plain. Dick would start telling stories about six p.m., and he had a full repertory. He spoke fluent French and Spanish, and he surprised more than a few visitors telling jokes in those languages. Even later in life, we would ask him to recount again when he and his brother Prent, back in Iowa, hoisted an outhouse onto their neighbor’s roof as a Halloween prank; when he stowed away on a ship from Puerto Rico to New York; when his friend ordered breakfast in Brazil, only to be delivered riding horses; and when he kept his fraternity brothers in bathtub gin – and the bathtub was in the local constable’s boarding house. Frequently some event would trigger his memory, and he would remember a new story, like getting caught by the Spanish police after a high-speed boat chase for smuggling cigarettes from Tangiers. With all of his escapades, he never spent a day in jail! His approach to business reflected this spirit. His goals were high, and he took risks. He started out in the import-export field before WWII – after his plan to sail a boat from Boston and trade for African gold came to naught. His companies produced textiles and shirts in Japan, mined iron ore in Canada, and served Dogpatch fare at L’il Abner’s Restaurants in Kentucky. In the end, he was a government bureaucrat in Washington which did not exactly please him, but it gave him a pension (and a secure retirement) and he never regretted having gone for the brass ring. It’s just that the ring eluded him. Dick was a superb athlete – football player in high school, a lacrosse All American at Dartmouth College, a Golden Gloves champ in Chicago, a skier, and well into his 80s, a tenacious tennis player. Last year his Florida doctor said, “When I looked at the test results, I expected to see a shriveled man barely standing. Imagine my astonishment when Dick told me that he came to my office from playing two sets of tennis!” Dick did not like to lose, and pity the folk who failed to take the game as seriously as he, whether poker or backgammon. Over the years more than one card table went flying. Dick exuded optimism and loved to be with people. He kept friendships from college, from his residences abroad, and from every stage of his life. He and Margaret treasured their family and their friends, many of whom who are here today, like Barbara and Flavel, and Bert and Gaham, Jean and Virginia, Louise, Venda, Bob and Ruth. Thank you. Dick did not do such a good job explaining the birds and bees, but he introduced Perri, Susan, Rich and Peter to fishing, to self-confidence, and to the value of truthfulness. He cheered us on in our careers and sympathized with us in our travails. When we came to him for advice, his judgment was always sound. Though at times impulsive in his own affairs, he urged patience and hard work for things to work out okay. And they did. Saying goodbye to our father Dick is not easy. But Dad – for your optimism, adventurousness, and your love for life – THANK YOU. “In our Father’s house, there are many mansions,” and with your own parents and with your beloved daughter and our sister Perri, may you and Mom rest there in peace. ***** |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Return to Table of Contents Return to Families Index Return to Home Page