Much-Traveled Warrior

Ellsworth’s War Companion Comes to U. S.

Born in England

Watt, if he could talk, would undoubtedly disclose many more things than his master has told of him, perhaps even elaborating on those times when he took part in the invasion of Italy, entering Poggia the first day the airfields were taken; o when he was lost in Naples after escaping from the boat the evening before he was to return to England with his master; or when he was in England in quarantine for six months after returning from the Mediterranean Theater, and was kenneled next to General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s dog, with whom he undoubtedly became quite chummy. But Watt cannot talk as humans, so his story, a really remarkable one, one of a returning dog-hero, must necessarily be told by Lieut. Ellsworth. Born in England on Feb. 17, 1942, Watt was named after a famous race horse, winner of the 1942 English Derby. His father and mother were both English champions. When he reached the age of nine weeks, Lieut. Ellsworth purchased him in Berkshire, England, shortly after which he was smuggled out of the country onto a boat bound for North Africa.Battalion Mascot

Discovered before sailing, Watt’s unknown exciting career looked to be stopped before it had started until the London War Office gave permission to Lieut. Ellsworth and Lieut. Tom Braden to take him to Africa with them. Several months in the sand, heat and flies of Libya were Watt’s first experiences with the British Eight Army. There he was adopted as official battalion mascot of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and there his food, like any soldier in the front lines was often insufficient and more than once, non-existent. He always slept on Lieut. Ellsworth’s camp bed at night, and accompanied the Dubuquer wherever he went, on night patrols by foot or jeep, depending on how reconnaissance was carried out. He rode in tanks, armored cars, motorcycles, all types of boats, carriers, trucks and other armored vehicles as in an armored brigade battalion such as the Rifle Corps commanded by General Montgomery. With the uncanny perception belonging to a canine, Watt soon learned to pick up the whistle of enemy shells in the air seconds before the human ear was able to detect, and his master stated that the dog took cover in slit trenches faster than any other ‘soldier’ in the front lines. He chased Arabs and Italians, never Britishers, the former of whom used to come around the camp at night to pilfer whatever they could lay their hands on, having learned to distinguish the difference in dress between the men, and sensed fear of enemy troops when enemy shells came over, and was frightened. “On the other hand, Watt was not bothered by small arms fire of our artillery,” Lieut. Ellsworth remembered. “He seemed to know the difference between when to hid and when not to.”Aided in Invasion

Following the African campaign, Watt was a part of the forces invading Italy, a landing made on a tank landing craft. Later he was with the Rifle Corps in the battles of Termolt, the Trigno River, Sinelio River, and the first few days of the Sangro River, with the Eighth Army in Paglietta, he was privileged to be petted by the commanding general himself, Montgomery, a day that will undoubtedly go down in his doggy mind as one of much import. There were many pets in Lieut. Ellsworth’s battalion, but Watt was the only one given permission, and the by the commanding brigadier general, to return to England with the battalion in February of this year. When the ship was anchored in Naples, scheduled to sail to the following morning, Watt escaped and spent the night on the wharf, being noticed at 8:30 o’clock the following morning by Lieut. Braden. All gangways were up, so Braden went over the side on a rope ladder, put the dog in a kit bag, and Lieut. Ellsworth hauled him up to deck with a rope. Fifteen minutes later the vessel sailed for England, Watt safely aboard. Upon arrival in England, the dog went into six months quarantine, an English law, and at that time was quartered next to the Eisenhower canine, Leiuts. Ellsworth and Branden flew back to the States, leaving Watt behind, and only last week, Watt arrived back from there via the “City of Glasgow” in charge of the ship’s cook, after a three week’s voyage. Watt’s trip across this month was his fifth sea voyage of the war. He took a train to Dubuque from the Eastern port, and will now spend the duration of the war with Mrs. Ellsworth at the home of her parents at 879 West Third Street. He has a bad front leg injured when a puppy and has had insufficient medical care, so he’s actually in Dubuque to “build up,” Lieut. Ellsworth explained.Has Only One Trick

Perhaps Dubuque will seem a little “tame” in comparing it with the many places he has been, including London, Tripoli, Tunis, Glasgow, Gibraltar, Algiers, Bari, Belfast, ruins of castles in England and Wales, Pompeii, Malta, Pantelleria, Lampadusa, and Mt. Vesuvius. He had, as recounted before, chased pigeons on the very lawn at Buckingham Palace; swum in the blue Mediterranean; walked about the native casbah at Algiers, Stone Henge in Wiltshire, the Kasserine Pass, Mareth Line, the ruins of Carthage, the Appeninne Mountains in Italy, a Fascist prison in Lucrea, Italy, and even spent five days and five nights at one time during his Army career crossing Africa in a French “40 and 8” boxcar. His only real dog trick, his master tells, is shaking hands. A really human understanding he has gather, however, is the knowledge of what an air raid siren means, at which time his ears go flat. ‘Till this day, he is nervous when planes go overhead, undoubtedly remembering the strafing incidents in North Africa. Would Lieut. Ellsworth advise soldiers to take dogs to war with them, he was asked. “Definitely no, although they are worth the trouble,” he replied. “There’s too much chance of separation in the end.” But Watt was indeed a comfort to Lieut. Ellsworth and Lieut. Braden. ”From June to November, 1943, we had no mail, and Watt was the most wonderful morale builder we could possibly have had,” Lieut. Ellsworth said, with an affectionate pat in the region of Watt’s black ear.Source: The Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, Dubuque, Iowa, June 25, 1944

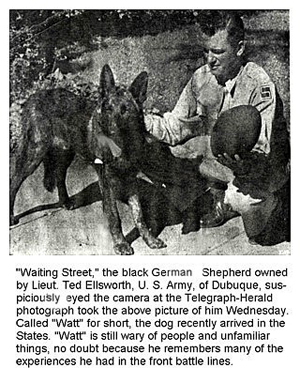

![]()