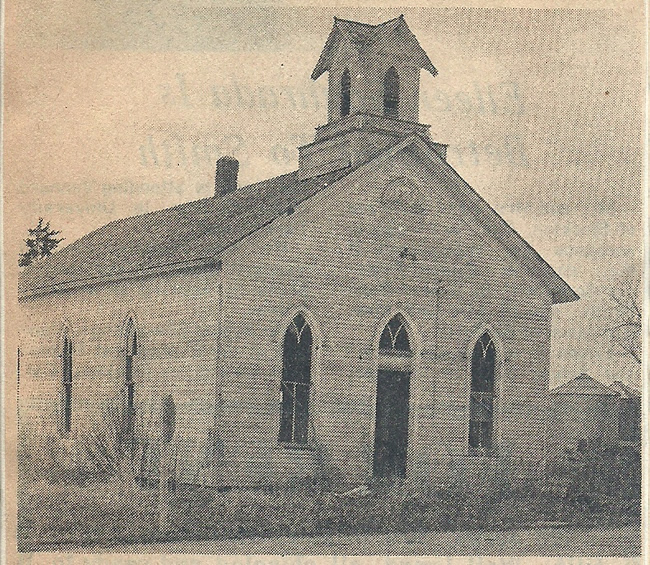

Platteville Church

Platteville Church

Tall pines rise high above the rolling Iowa countryside that is checkered with green wheat fields and yellowish corn stubble. Their dark green boughs guide the visitor to Platteville.

Nearby, a shorter Macintosh apple tree, planted before the Civil War, grows and still bears fruit.

The old Methodist Church, grayed by the years, stands on the northwest corner of the crossroads, its door ajar and its windows broken out. It is the only remaining public building in what was once a bustling village of 400 or more population in the southwest corner of Iowa.

Closeby, however, live two longtime residents of the Platteville area, Mrs. Hazel Blane and Mrs. Ferne Straight, and through their memories the visitor gets a glimpse of Platteville as it once was.

Mrs. Blane's grandparents, Adam and Susan Propst, came to Taylor County in 1850, and her grandfather Jeremiah Morgan, after walking from Siota County, Ohio, settled near Platteville in 1857. It was the Propsts who planted the apple tree.

Mrs. Straight's grandfather was Dr. J.R. Standley, and her father was his son, Dr. J.P. Standley. Both were early physicians in the area. It was Dr. J.R. Standley who planted the "Platteville pines."

The doctors Standley had a penchant for unusual animals. J.R. Standley raised angora goats,

selling them all over Iowa. Later, Dr. J.P. Standley raised elk just north of Platteville in a fenced preserve.

The first building in Platteville, the ladies agree, was Tom Larsen's log cabin, built in 1848.

Ten acres were set aside at about this same time for the town, and in 1855, the town name was recorded in state annals.

Streets were laid out, and community well installed at the intersection of Pine and Green Streets.

The village boasted besides the church, which was built in 1873, the "Bo" Dixon Inn, two hotels, two livery barns, and a general store with drug store. The first general store, which advertised "everything from a threshing machine to a needle," burned, but others took its place.

Dr. J.R. Standley owned one of these, as well as stores in Sheridan and New Market. Above the Platteville store, there was a youth center where the young people gathered.

Mrs. Blane's Uncle Dan Propst operated a furniture--and coffin-making establishment. Mrs. Straight recalls that, in addition to coffins and furniture, he built "everything from plowshares to houses.

He lived long and at one time was honored as the oldest Mason in Iowa.

There was a millinery and dressmaking shop, a cobbler, a blacksmith and, later, a telephone office. There were three doctors. Mrs. Straight says her father charged from $2.50 to $4 for house calls and often took produce and livestock in payment for his services.

There were literary societies in Platteville and Mrs. Blane says home talent performers put on shows "as good as Hollywood's." Square dancing was popular, too, with the dances held often in homes.

Mrs. Blane's father was fiddler. Later, Charles Kemery made stringed instruments and one of the fine violins he carved and strung is a keepsake in the Blane family.

In those early days, Indians still roamed the Iowa countryside. The Platteville Cemetery was a favorite stopping place for some of the tribes.

Mrs. Straight says her grandparents reported that they were never troublesome, but some residents of Platteville, would, nevertheless, go to a fort on a farm west of town for protection when the Redskins arrived.

Once, Mrs. Straight's grandfather went to visit the Indians taking his little daughter, Ida with him. A squaw wanted to trade her papoose for the little girl, and Dr. Standley did.

He took the Indian baby home and then went back to the cemetery to retrive his own baby.

The Indians had moved on, and the doctor had to chase them some distance to make the exchange.

Later, a squaw taught the same Ida, who married Asa Terril and was the mother of Dr. J. Terril, to make cough medicine from sumac berries mixed half and half with sugar. The mixture is simmered until it is thick. It is a remedy Mrs. Straight used for her own children.

Among Mrs. Blane's souvenirs of those times is a huge arrow head, which was found in a stream that runs through her farm. She also remembers her grandfather telling about some Indians who came to the farm looking for oats. The Indians were accompanied by some skunks, and the skunks were accompanied by their usual odor!

Both ladies remember stories of "Bo" Dixon's Inn, a place where "the men could drink a little." The drinking angered the Plattevillewomen, but a plan they developed to dynamite the place literally "fizzled out" when the fuse failed to light.

Another anecdote from the early days has to do with a black cook who worked at Larsen's

Hotel. It was the custom in those days for travelers to eat their evening meal at the hotel, then gather, often with some of the townspeople, in the lobby or living room.

This all happened as usual

one night. The cook was still in

the kitchen tidying up after the

meal, when two young black men entered.

Jennie, the cook, came out of the kitchen, saw them, and said, "Oh, my God, my sons!"

They had been slaves when Jennie had left them somewhere in the South to come North. When the Civil War freed them, they came North to find their mother. It was a happy reunion.

The Platteville Methodist Church cost $2,000 to build, and Mrs. Blane remembers that services were often held on Sunday afternoons in the early 1900's.

Some Sunday School superintendents were Ida Terril, Dora Standley and Clara Bescoe.

Services were held until 1940, when World War II made it difficult for members to attend, and, finally, in the late 1940's the church closed for good.

The Platteville School was first housed in a log structure. This was 1856, and Truman Straight, grandfather of Mrs. Straight's husband, Truman, was an early teacher. Later, a frame building was built.

Mrs. Blane remembers the country schools, among them Platteville, of the early 1900's fondly.

There was a big round wood stove, she says, and double seats and desks.

Each September, the children would choose their seats and seatmates for the term.

The smaller children could sit in front, the larger in back.

Each child had a slate and slate pencil as well as a five-cent tablet and new lead pencil. Standard equipment also included a cloth or sponge to wipe the slate.

School "took up" at 9 a.m., and opening exercises included singing with the teacher accompanying on the organ and a story, often from the Bible.

Reading, writing and arithmetic, broken by recess and lunch out of tin pails, was the order of the day. Lunch was eaten outside in nice weather.

In the afternoon, it was more study and recitation.

Both Platteville natives remember threshing, wood-getting and corn-shucking crews.

Bountiful feasts prepared by the ladies were important parts of these necessary rites, and tables were heaped with freshly dressed fried chickens, canned beef and pork and other company fare.

Mrs. Blane remembers the advent of the telephone and says the first poles were cut from burr and white oak. The phones cost $10 each, and $4 for switch fees.

The people on the line could listen in while someone played the organ or one of the new Edison phonographs that were becoming popular just then.

A man named George Brown,

whom the ladies say was "a

mechanical genius" kept the telephones in repair with help

from the other men in the community.

The fact that the Chicago Great Western Railroad built its tracks through Blockton instead of Platteville may have spelled the beginning of the end for the little community.

Gradually, most of the townspeople moved away, and the streets and buildings disappeared into the cornfields.

Today, Mrs. Blane and Mrs. Straight are two of the few descendants of the original settlers who remain.