BEGINNINGS OF THE RAFTING INDUSTRY

33

The first lumber run from Lake Saint Croix was from marine Mills, in 1839;

the first logs from Stillwater to Saint Louis by S.B. Hanks, 1843;

The last, a lumber raft in Augusta, 1915, to Fort Madison, Iowa, by the

Steamer 'Ottumwa Belle', W.L. Hunter, pilot.

The Mississippi River Logging Company began operations on the

Chippewa

river, and took over the work begun by the Beef Slough Boom Company, in

1871, and increased the output steadily, reaching its maximum about 1892,

when over 600,000,000 feet passed through its booms in a season.

In 1889-1890, the works were moved to West Newton , from which

three hundred million to six hundred million feet were turned out annually,

until 1909, when the exhaustion of the timber supply caused a final shutdown.

The first lumber was rafted down the Chippewa river in 1831, and

from a

small beginning the industry developed rapidly.

The following large companies were engaged in sawing pine lumber

and

sending it down the Chippewa and Mississippi rivers:

The Badger State Lumber Company

The Eau Claire Lumber Company

The Daniel Shaw Lumber Company

The Lafayette Lumber Company

The Northwestern Lumber Company

The Union Lumber Company

34

The Valley Lumber Company

The Dells Lumber Company

The Sherman Lumber Company

Also Ingram, Kennedy and Company; the great Knapp Stout and Company

which

cut two billion feet of lumber in sixty years, from 1836 to 1896, and the

Chippewa Lumber & Boom Company, which cut 325, 000 feet a day, with 75,ooo

lath on the side.

There was lively work bringing this down the Chippewa to Read's

Landing,

where small rafts or pieces were made up into a large Mississippi

raft for downriver.

Sawed lumber and timber were fitted at the rear of the mill into a

frame

or heavy crate sixteen feet wide, thirty two feet long and twelve to

twenty inches deep made of grub plank two inches by twelve inches, held

together by heavy two-inch pins of hickory or oak, holding top and

bottom sides and end all solid together. This made a 'crib', the unit which

was built on a moveable platform that, when tilted, would let the crib, slide

down, into the river.

A number of these cribs, fastened in regular strings by strong

couplings

of planks fore and aft and also crosswise, would make a raft of perhaps

twenty- four cribs for the Chippewa, and from one hundred and twenty to

one hundred and sixty cribs for the Mississippi.

Until the middles sixties, all rafts of both logs and lumber, were

floated down by the current and kept in the channel and clear of sand bars,

heads of islands, bridge piers and other besetting dangers, by a crew of

strong, lusty men, who used large oars or sweeps on the bow and stern.

There was an oar at each end of every string of cribs, so that a raft of ten

strings had had a bow crew of the ten best men, and the other ten pulled on ...

35

... the stern. All were under the direction of the pilot who hired and paid

them off and usually had fair control of them.

The first trace of rafting on Black river was in 1844,

when Myrick and

Miller sent some logs to Saint Louis, but about two years before this, the

Mormons had got out some timber for their buildings at Nauvoo.

This timber was sawed in the mill of Jacob Spaulding at Black River

Falls.

The mill, built in 1839, seems to have been the first to begin cutting on

Black river. The greatest output was in 1881- 250,000,000 feet.

Governor C.C. Washburn, prominent in lumbering on Black river, had

his

home in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, and organized the LaCrosse Lumber Company,

in 1871. He was born in Maine, taught in a private school in Davenport in

1839, and in 1840 was elected county surveyor of Rock Island County.

John Paul, C.L. Colman, N.B. Holway, W.H. Polleys, G.C. Hixon, Abner

Gile, Oran and Levi Withee, Sawyer and Austin, A.W. Pettibone, P.S. Davidson, G.B. Trow and McDonald Brothers, were all engaged in extensive logging

and lumber operations.

The earliest lumbering was probably on the Wisconsin river. Pierre

Grignon

had a sawmill operating in 1822, and possibly earlier, on Dutchman's creek.

Some of the product was floated out and down the Mississippi, but records are

very meager. By treaty with the Indians in

1830, Governor Henry Dodge secured the rights for lumbering, and by 1840 many

mills were located, and some in operation.

The first raft taken through to Saint Louis of which we have

reliable

record, was run by Honorable Henry Merrill, who took charge of it at Portage,

Wisconsin, ...

36

... rebuilt and refitted it at the mouth of the Wisconsin river, and delivered it

in Saint Louis, in 1839.The early saw mills in Galena and Dubuque were

supplied with logs prior to this long trip to Saint Louis.

In 1857, three thousand men were engaged in lumbering on the Wisconsin,

and the value of the log crop was estimated at $4,000,000.00.

As all the lumber had to be floated out of the Wisconsin and down the

Mississippi, rafting grew into a great business, and was handled quite

systematically, by a hardy, rough, but industrious and reliable lot of men,

working under such floating-raft pilots as Dave Philomalee, Bill Skinner,

Bill Simmons, Wild Penney Joe Blow, and Sandy McPhail.

Some went through direct to Saint Louis, others peddled by string

or crib

to dealers in the towns along the way, and the trips would often end

at Davenport, Muscatine, or Quincy. Then the crew would take passage on a

steamboat going north to start another trip down. They had no work to do

going up river, and usually made it one long carousal, so that by the time

they reached the mouth of the 'Wisconsin' or Black river they were broke

and glad to go to work again.

Some of the pilots worked by the month, others by the season or

trip,

the 'company' paying all expenses and taking all the chances; but a few had

their own kits and ran the rafts under contract-so much per thousand feet, or

so much a string.

From 1870 to 1875, I had considerable acquaintance with these

raftsmen, on

account of my father's lumber yard at Princeton, Iowa,

which received all its supply from floating rafts, mainly from the Wisconsin.

Daniel Stanchfield cut the first logs on the Upper Mississippi,

above

Saint Anthony's Falls, in 1848.

37

These logs were sawed into lumber by the first mill in Minneapolis, owned by

Franklin Steele and others. It began sawing in September, 1848, by

water power.

The business increased rapidly, and settles and immigrants poured

into

Saint Paul and Minneapolis. In 1856, the surveyor-general reported scaling

6,000,000 feet of logs for Borup and Oakes alone. These logs were run over

the falls to be caught in the Saint Paul boom, where they were rafted

and floated down river to other sawmills, a large number going to Saint

Louis.

Rum river was cleared of obstructions in 1850, and logging on this

tributary increased from 6,000,000 feet in 1850, to 32,000,000

feet in 1854.

The output of the Upper Mississippi above Saint Anthony's Falls

rose to

678,000,000 feet in 1899, and totaled 11,000,000,000 feet for the

fifty-two years from 1848 to 1899 inclusive.

From 1869 to 1887 very few if any logs passed over Saint Anthony's

Falls for down-river mills, as the many large mills in Minneapolis sawed

all

that came down from the Upper Mississippi and its tributaries within the

site of Minnesota.

In 1888 the Saint Paul boom was opened, and rafting logs for

down-river

mills was carried on here quite successful. When it finally closed, in1913,

the surveyor's record showed an output of 1,555,854,900 feet during the

twenty-four years.

Some pilots took pride in their work and the appearance and good

performance of the crew, and made few changes during the season. There was

marked difference piloting even a floating raft. A bright, sober,

intelligent pilot, who learned the drafts or water at different stages,

would make better time and give the …

38

... men less work in bucking the oars. Such pilots could always get rafts to

run

and men to run them.

On lumber rafts, the crew usually had a board shanty where the cooking was

done, and little dog houses, improvised to sleep in. On long trips, such as

from Stillwater or Read's Landing, Minnesota to Saint Louis, they would fix

up comfortable bunks, as they had all kinds of lumber to use and a

good floor to start on. On log rafts they usually depended on flimsy tents

provided by the pilot, and the conveniences of life were very meager, but

the work was healthful, and the life, and excitement, in the open pure air,

gave them good appetites and excellent digestion. They usually had plenty of

good, plain food, and strong coffee. They seldom had any ice, in the hottest

weather, or any milk. Sometimes delayed on a long hard trip, when

the pilot's money or credit gave out, these men were just as resourceful as

any of General Sherman's soldiers, on their March to the Sea.

The country above Dubuque was very sparsely settled, and the little

towns

far apart, but it is pleasant to reflect that that there is no record

of a raftman dying of hunger. An anger farmer, who missed a fat two-year

old heifer one morning after a raft had passed down, overtook the raft by

a long, hard row in a heavy skiff. The dressed carcass lay on the logs near

the center of the raft, covered with a piece of white canvas. The crew was

divided and crouched at the corners of the raft, while the old French pilot

sat alone with his head down when the farmer appeared and questioned him. Old

George said, "My friend, I'm glad to see you. I'm in

big trouble. My crew are all afraid of me." "How so? You

see." he replied,

"that white ting down …

39

... there? - small pox, one of my best men, the cook. I stay and work with him all night

but taint no use. Now, my friend, you look like brave man. I want you to

help me take the cook ashore and bury him." But the farmer was gone; nearly

fell in the river in his excitement and hurry to get away.

On reaching a raft's destination - Dubuque, Burlington Iowa,

Hannibal

Missouri, Saint Louis or elsewhere- the pilot would ship his kit and provide

deck passage on a northbound steamboat back up the river. The pilot, of

course, took cabin passage. These returning had no work to do going back

up river. There were often several raft crew on each steamer. Having been

paid at the down trip, all had money. Every boat had a bar, and 'red liquor'

was in demand. The fighting was confined to the lower or main deck, where it

annoyed only the boat's crew and other deck passengers. On one occasion,

though, these orgies developed into a riot, on the steamer

'Dubuque', and several were killed or driven overboard and drowned.

The rioters then took charge of the boat for a few hours, and cabin passengers were in terror, until officers intercepted the 'Dubuque' at the

Clinton, Iowa bridge, arrested the rioters and took them ashore for trial.

There has been much noise made about the "riot on the steamer

'Dubuque'" in

books and magazines, especially in recent years.

The trouble started easily through the mistake or oversight of the

captain

or mate in placing a negro at the head of the main stairway forward to

keep

Irish raftmen from entering the cabin to get their

'Mornings or 'Eye-Opener'.

There was a bar on the 'Dubuque' in

the front end …

40

... of the cabin and 'lower-deck' passengers were welcome patrons as rule.

These raftman had been patronizing the bar quite liberally all the way up but

the bartender accustomed to handling them kept them in good humor

and within a safe limit; but while lying at Rock Island and Davenport some

of them drank a lot up-town after the boat's bar was closed for the night.

She left early in the morning and when these men woke up after the

night's

debauch they wanted whisky and wanted it bad.

The officer in charge should have been prepared to take care of

this

matter. It was an awful mistake to put a negro there to meet the situation.

Deck passengers were not allowed to eat in the cabin at all; they

got grub

from the kitchen down on the main deck. It was whiskey they wanted,

not breakfast, and it was no place for a in front to turn them back

from the bar.

I don't know what river these raftmen came from but think they were

from the Wisconsin, as the majority of them were Irish; while on the

Black, Chippewa and Saint Croix rivers, the Canadians and Scandinavians

were the most numerous.

I never heard raftmen from Black river spoken of as more belligerent

than

others; nor did I ever learn of a single instance of a real raftman

assaulting injuring a woman or a child. They would fight when in liquor,

and this was not unusual on shore in those days.

When a boy I saw more fighting and more blood shed on one Saturday

night

in the little town of Princeton than I saw among raftman during my

twenty years among them.

The riot on the 'Dubuque' was the only affair of the kind that

happened

during the seventy-five years of the …

41

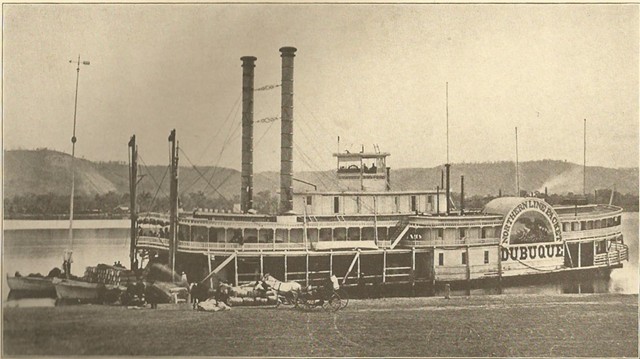

Picture of the Steamboat Dubuque

This successful steamer, owned by the Northern Line, was built at Pittsburg, Pa., in 1867. She was 233 feet long, 36-foot beam, and 62 feet wide, over all. The "riot" occurred on her at Hampton, Ill., July, 1869. She burned in Alton Slough, March, 1879. From photograph taken at Winnona, Minn.

|

43

... rafting period. Because it was so unusual, much was made of it.

While clerk on the 'Silver Wave' late in the fall of 1879 we had a

husky crew of real raftmen which included 'Ole' a big Swede and Tom

Cleeland an Irishman of good size and build, who was called one of the

best men 'in the woods'.

We had to lay over night at LeClaire on one way down. All the cabin

crew

(captain, pilot, mate, engineers and cooks) lived in LeClaire, our home port,

and all of them had gone home for the night leaving me in charge.

Before leaving, the mate reminded me not to let the deck crew have

much

money; so when they were free to go up-town all came up together

and I handed one or two dollars each and told them that was all they could

have -'mates orders.' All O.K.

At 10:30 P.M. five or six of them came back for more money. I tried

to

persuade them not to go up-town again- to go down and turn in for a little

sleep before four o'clock but they were insistent. So I gave in gracefully,

saying, "Boys, you know this is my first season on this boat

and I don't like to break orders, but you fellows have always treated me

nice, so here's a dollar apiece; spend that and come back and turn in for

the for the mate will be after you at four o'clock, remember." "Oh das

alright." "You been dam good feller" said "Ole', and of they

went and I

thought I was done with them.

Just before midnight I heard them come on. After some noisy talk

back

in the deck room, four of them, including Ole and Tom came up-stairs and

into the cabin and demanded more money.

I was stirring up the fire with a big poker of three- …

44

... quarter-inch iron. I swung the door shut with the poker stuck down in the

down in the fire and the other end out.

I told them the safe was locked and I was going to

bed, "No more money

tonight, Olie."Big Olie answered, "Yas; das all right," and went

out.

The two smaller men again demanded more money-all their money. I opened the

front door and succeeded in persuading one to go out and down but I

had to use force on his partner, but got him out and closed the door. Then

Tom Cleeland lit his pipe and remarked "That is a rough way to put a man

out".

"Well," said I, "he wouldn't go out when I told him

to- I had to put him

out , I'm running this place, ain't I, Tom?"

Tom smilled and said, "Well you can't put me out that

way."

"No Tom, I know that, you're too big for me and I hear you're

a hard man

to handle. But Tom, I'm in charge her and when I start to put you out, I'm

going to do it."

"The hell you will. Just try it." said Tom. By this time

with my old

gloves on I grabbed the end of the log poker, jerked it out of the fire,

about eighteen inches of it red hot, and made for him, and in full tones

told him to fly or I would mark him for life. He caught my idea instantly and

acted on my advice. I had no trouble after that- we got along fine until the

season closed.

Carrying these raft crews and their kits back up river, while

sometimes

not a pleasant business, was always a profitable one, adding a large amount

to the earnings of the packet companies, with very little …

45

... added expense. Naturally the packet companies were against the use of

towboats helping these rafts down river and carrying back the crew.

One of the Northern Line packets, going up river in the night, ran

into a

raft, under way, and did it considerable damage. George Tromley, the

pilot of the raft, made a claim on the Packet Company, when he delivered

his raft to Saint Louis. He was told to leave his bill and they would submit

it to Captain Hill when the steamer 'Dubuque' returned. Captain Hill refused

to o.k. the bill and Captain Tromley's lawyer libeled the steamer

'Dubuque' in United States District court. The bill was then promptly paid,

with costs.

Some time later, Mr. Tromley, with his crew, were in Saint Louis to

go

back up river on the first, which happened to be the 'Dubuque.' Not long

after starting, Captain Hill met Mr. Tromley near the office and bar, and

began raking him for making such a big noise to the company and libeling the

boat. Mr. Tromley, in his pleasing manner and rich Canadian dialect,

said," Well, Captain Hill, I bring my crew and your boat today, don't I

?"

" Yes." "I pay my way for all my people, ain't that so, Mr.

Clerk?" "Yes, that's true, Mr. Tromley." "I ride on your boat before, ain't I,

wit my crew

and kit?" "Oh, yes, Mr. Tromley, you have traveled with us many times.

You are a good customer." "Always pay my way, don't I, Mr. Clerk?"

"Yes,indeed, Mr.Tromley." "Then" turning to Captain Hill

with his peculiar

smile, he said, "Now Captain, you hear what the clerk say, and and these

gentlemen (passengers) they all here too. Now when you come and bring your

boat and crew and take ride on my raft, don't you think it only fair you pay

your fare same as I ?"

46

Captain Hill was glad to call all hands to 'splice the main brace'

before

supper, and all trouble was over. Mr. Tromley was in many ways the

brightest and most interesting character I met in forty years on the river,

three of which were spent under his tutorship in learning the river.

Some years later Pilot Tromley was running on the rafter 'Silver

Crescent.'

Captain Mitchell, a much younger man, was very excited and one

day after striking the LaCrosse bridge he got terribly worked up. Mr. Tromley took charge of the affair and in a few hours the crew had the raft in

good shape again and the 'Silver Crescent' shoving at full head towards its

destination.

After clearing up, Captain Mitchell went up to the pilot-house and

sat

down quietly holding his face in his hand, for several minutes.

Then, rousing he said, "Mr. Tromley, I believe I'm going

crazy."

Mr. Tromley turned around and with a merry twinkle in his eyes and

in the

kindest manner said, " Why my dear friend! Are you just finding that

out? There's many people on this boat could told you dat good while ago.

"Now captain let me tell you something! It ain't no use

to get so dam

excite. I have been on this river long time; more than you have; and have had

all kinds of trouble raf's broke up, raf's ground on san bar, hit bridges,

caught in fog or storm but I never yet heard of a saw log come up in

pilot-house and kill a pilot." The captain laughed heartily and it

really

helped him.

HISTORY

HISTORY