BEEF SLOUGH

47

The Beef Slough Boom and Improvement

Company was organized in 1867, and

chartered by the state of Wisconsin to catch, sort, raft, and scale all logs

coming down the Chippewa. These were turned into Beef Slough by a sheer boom

at the head, and jam booms farther down were

uses for holding the run in high water. The company was allowed to charge

seventy-five cents per thousand feet for logs, and two cents each for

cross ties.

It was soon demonstrated that this was a great improvement over

separate

operations by individual owners, and when this company was taken

over by the Mississippi River Logging Company, in 1873, it was soon evident

that the sufficient capital and vigorous and intelligent management of

this

organization would take excellent care of the Chippewa outfit and keep

the large mills regularly supplied, as long as the timber supply held out.

Beef Slough is a branch mouth of the Chippewa river, leaving the

main

stream at Round Hill, and following down along the high Wisconsin bluffs

for about twelve miles, opening into the Mississippi just above the town of

Alma, Wisconsin.

By dredging and digging at its head, and removing obstructions in

its

course, the diversion was much increased into the slough, and then a long,

heavy sheer boom placed diagonally across the Chippewa, not only turned

all the logs into Beef Slough, but greatly accelerated the current and

gave good water to work on.

48

Thousands of piling were driven and many booms placed, and pockets

and

chutes arranged, so that the big crops of logs were saved. They were sorted,

rafted and scaled, with check works and guy line pins, all ready

for tow boats to hitch into, and were taken away and delivered to the mills

down river as fast as the seventy-five steamboats on the Upper Mississippi

could go up and down.

During the busy season, between 1200 and 1500 men were employed in

Beef Slough, and the work was handled with great system and energy.

While Mr. Weyerhaeuser was seldom seen at the Slough, his spirit

was

always evident. Mr. Irvine in the earlier years lived at Wabasha, and was at

the office nearly every day, with George Scott directly in charge. Other men

were E.Douglas, at the rafting works, D.J. McKenzie, head scaler, Kinney

McKenzie, in charge of the 'dropping', Duncan McGillivray as assignment and delivery clerk, and Pet Short handling the catch boom at the mouth.

The steamer 'Hartford' under Captain Henry Buisson, was busy

dropping

out half rafts to places of safety, where they would lay at owner's risk

until taken away by some other boat.

The steamer 'Jesse Bill,' under Captain Lew Martin, was doing all

kinds

of company work, while the 'Little Hoddie' was 'bowing out' and towing

batteaux crews back up to the works.

Twice a day the local steam packet 'Lion' passed through the lower

end of

the Slough, landing at the office to let off mail, passengers, and a

little freight, and then out through the 'cut off' on her way to Wabasha,

Minnesota

There was no railroad on the Wisconsin side, and …

49

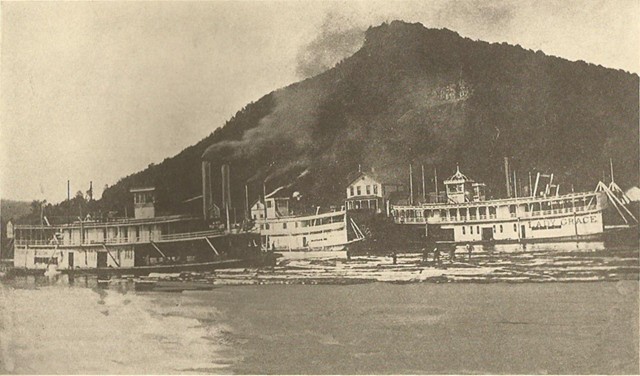

Picture: Steamers Stillwater and Lady Grace

The Robert Dodds shown in the foreground, is going out with one-half of her raft. The view shows a group of raft-boats at the office of the M. R. L. Co., in Beef Slough, which in 1884 turned-out 647,000,000 feet of logs and kept 75 rowboats busy. |

51

Captain H.C. Wilcox

had a nice trade between Alma, Wisconsin, and Wabasha, Minnesota, making two

round trips a day.

All the bosses and many of the men working in Beef Slough were

Scotch-

Canadians, who had been lumberjacks back home on the Ottawa or Saint

Maurice, and their quick, decisive speech with the burr on it, pleased me

very much. You could not throw a boom plug at any crew and not hit a

Macdonald, or a Mackenzie, and probably get one back from a Duncan.

Each raft was composed of two pieces (halves) of three brails each.

A brail of logs was six hundred feet long and forty-five feet wide. The rim was

made of the longest logs, fastened at the ends with about a thirty-inch lap,

by a short, heavy chain of three links. A two -inch hole was bored nine

inches deep in each log, and a two-inch oak or ironwood pin, with a head on

it was put through an end link of the chain , and driven hard into the

hole

in the boom log. These logs so fastened, made a strong boom or frame( with

just enough flexibility to suit the job) into which the loose logs were

carried by the current and skillfully placed endwise with the current, by

men, using pike poles and peavies. Then one-half-inch cross wires were placed

and tightened, to hold the boom and logs together

and prevent spreading.

When a brail was completed, two men with a double-headed skiff or

batteaux, would drop it down, by the current, one to three miles, and snub

it in, where later two more brails would be landed beside it. Then a fitting

crew would come a drop the three brails even at the stern, fasten them

together, build 'snubbing works' and other things necessary to complete

a 'piece' or 'half raft' all ready for a boat to hitch into.

52

When the tow-boat came to take these pieces away, she would move alongside

slowly, while the mate and his men threw off the cross lines, reaching across

the three brails, and the windlass poles, with which they were drawn up and

made taut.

Then they would turn the boat around (not by any means an east task

in such a close place), hitch her into the stern of the raft, with headlines

straight out to the check works to back on, and breast lines from her head to

the right and left, to keep her stem, or nose, on the butting block,

and guy lines out from the midship or after-nigger to the stern corners of

the raft, to hold the boat in any desired position.

The butting block was a big log securely fastened, by timber and

chains,

to the stern boom, to tow on.

Then part of the crew ran out the long A line, running diagonally

across

from the outside booms, crossing X like in the middle (these to keep her

straight and prevent buckling), and others put on the corner lines to prevent

the heavy strain on the guy lines from pulling the corners back. The mate

with one or two good men, put on and tightened a heavy monkey line, to help

the butting block. When this was done, she was all ready to back

out, with the 'Little Hoddie' hitched in across the bow, to back or come

ahead, moving the bow to right or left, to clear the other pieces on either

side of the channel, just wide enough in places to let the bow through,

sometimes the outside booms rubbing on each side. The mate a few men

watched close to loosen her up if she caught anywhere.

Sometimes she would catch and foul, and tear a brail loose, or make

a

drive. Then came the call 'tie up, the catch boom is closing,' and a general

tie-up of two to three hours would follow, till the loose logs

ahead were …

53

...secured.

Usually, though, all went off wonderfully well, and she soon passed the

closing boom and out of the Slough into the Mississippi. Soon they tied up

under a bar or on the foot of an island, while the boat went back to the

Slough and got her second piece.

When coupled up, these two pieces made a raft two hundred and

seventy-five

feet wide and six hundred feet long. They contained 800,000 to 1,000,000 feet

of logs, weighed 3,500 tons, and covered three acres.

The output from Beef Slough was 12,000,000 feet in 1867, 26,000

feet in 1869, and 10,000,000 feet in 1870.

From the time the Mississippi River Logging Company took control,

in 1871,

the annual output increased quite steadily, until it reached 535,000,000 feet

in 1885, 405,000,000 feet in 1887, and 542,000,000

feet in 1889.

In 1889, the operations were transferred from Beef Slough to West

Newton

Slough, a little below, on the opposite side. They were conducted

by a new company, but it was composed of the same stockholders, and headed by

the same officers.

Not only the logs belonging to the 'pool,' as it was called, but

all logs

coming down the Chippewa were handled and delivered to their owners in

regular raft shape, on the regular charges allowed by the state charter.

There were over 2,000 different marks on the logs scaled and passed

through the Slough. The way this was done was certainly a fine demonstration of efficiency and square business methods.

West Newton reached the peak of its business in 1892, when 632,

150,000

feet of logs were rafted.

Using west Newton as a base required the driving of the loose logs

out of

the main mouth of the Chip- …

54

...pewa

at Read's Landing, and down the Mississippi to the head of the West Newton

Slough, and to place a big, long sheer boom above the mouth of

Beef Slough, to throw the logs over toward and into the head of West Newton

Slough.

These loose logs between the sheer boom and Read's were often too

thick to

run through, especially when the Chippewa was rising, and it was common for

steam boats to have to tie up for a few hours until the heavy run was over.

>From 1892 the output decreased steadily until 1904 when the 'great game'

ended for good. This was because the supply of pine accessible to the Chippewa

and its tributaries was exhausted.

In 1909, the Mississippi River logging Company of Clinton, Iowa was

dissolved, after a most highly successful career, during which nearly every one

of its members became millionaires.

During the period of its greatest activity, the officers were: Fred

Weyerhauser, of Rock island, Illinois, president; Artemus Lamb, of Clinton,

Iowa, vice-president and Thomas Irvine, Secretary.

The principal members of the company were:

| Youmans Brothers and Hodgins | Winona, Minnesota |

| Laird, Norton and Company | Winona, Minnesota |

| Winoan Lumber Company | Winona, Minnesota |

| W.J. Young and Company | Clinton, Iowa |

| C. Lamb and Son | Clinton, Iowa |

| D. Joyce | Lyons, Iowa |

| Dimock Gould and Company | Moline, Illinois |

| Weyerhauser and Denkmann | Rock Island, Illinois |

| Rock Island Lumber and Mfg, Company | Rock Island, Illinois |

| Musser lumber Company | Muscatine, Iowa |

| Hershey Lumber Company | Muscatine, Iowa |

| Shulenburg and Boeckler | Saint Louis, Missouri |

HISTORY

HISTORY