Pg 81

. . . “Special Order, No. 430. “WAR DEPARTMENT,

“ADJUTANT GENERAL’S OFFICE, WASHINGTON, Dec. 3, 1864

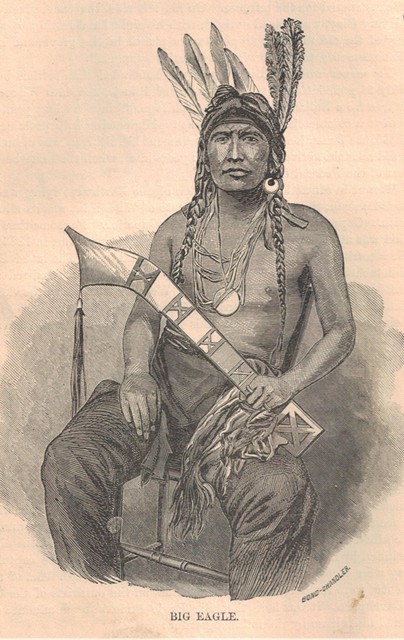

“Big Eagle, an Indian now in confinement at Davenport, Iowa, will, upon receipt of this order, be immediately released from confinement and set at liberty.

“By order of the President of the United States.

“Official: “E. D. TOWNSEND, Ass’t Adj’t Gen.

“CAPT. JAMES VANDERVENTER, Com’y Sub. Vols.

“Through Com’g Gen’l, Washington, D. C.”

Another Indian who figures more prominently than Big Eagle, and who was more cowardly in his nature, with his band of Modoc Indians, is noted in the annals of the New Northwest: we refer to Captain Jack. This distinguished Indian, noted for his cowardly murder of Gen. Canby, was a chief of Modoc tribe of Indians inhabiting the border lands between California and Oregon. This region of country comprises what is known as the “Lava Beds,” a tract of land described as utterly impenetrable, save by those savages who had made it their home.

The Modocs are known as an exceedingly fierce and treacherous race. They had, according to their own traditions, resided here for many generations, and at one time were exceedingly numerous and powerful. A famine carried off nearly half their numbers, and disease, indolence and the vices of the white man have reduced them to a poor, weak and insignificant tribe.

Soon after the settlement of California and Oregon, complaints began to be heard of massacres of emigrant trains passing through the Modoc country. In 1847, an emigrant train, comprising eighteen souls, was entirely destroyed at a place since known as “Bloody Point.” These occurrences caused the United States Government to appoint a peace commission, who, after repeated attempts, in 1864, made a treaty with the Modocs, Snakes and Klamaths, in which it was agreed on their part to remove to a reservation set apart for them in the southern part of Oregon.

With the exception of Captain Jack and a band of his followers, who remained at Clear Lake, about six miles from Klamath, all the Indians complied. The Modocs who went to the reservation were under chief Schonchin. Captain Jack remained at the lake without disturbance until 1869, when he was also induced to remove to the reservation. The Modocs and the Klamaths soon became involved in a quarrel, and Captain Jack and his band returned to the Lava Beds.

Several attempts were made by the Indian Commissioners to induce them to return to the reservation, and finally becoming involved in a . . .

Pg 82

. . . difficulty with the commissioner and his military escort, a fight ensued, in which the chief and his band were routed. They were greatly enraged, and on their retreat, before the day closed, killed eleven inoffensive whites.

The nation was aroused and immediate action demanded. A commission was at once appointed by the Government to see what could be done. It comprised the following persons: Gen. E. R. S. Canby, Rev. Dr. E. Thomas, a leading Methodist divine of California; Mr. A. B. Meacham, Judge Rosborough, of California, and a Mr. Dyer, of Oregon. After several interviews, in which the savages were always aggressive, often appearing with scalps in their belts, Bogus Charley came to the commission on the evening of April 10, 1873, and informed them that Capt. Jack and his band would have a “talk” to-morrow at a place near Clear Lake, about three miles distant. Here the Commissioners, accompanied by Charley, Riddle, the interpreter, and Boston Charley repaired. After the usual greeting the council proceedings commenced. On behalf of the Indians there were present: Capt. Jack, Black Jim, Schnac Nasty Jim, Ellen’s Man, and Hooker Jim. They had no guns, but carried pistols. After short speeches by Mr. Meacham, Gen. Canby and Dr. Thomas, Chief Schonchin arose to speak. He had scarcely proceeded when as if by preconcerted arrangement, Cap. Jack drew his pistol and shot Gen. Canby dead. In less than a minute a dozen shots were fired by the savages, and the massacre completed. Mr. Meacham was shot by Schonchin, and Dr. Thomas by Boston Charley. Mr. Dyer barely escaped, being fired at twice. Riddle, the interpreter, and his squaw escaped. The troops rushed to the spot where they found Gen. Canby and Dr. Thomas dead, and Mr. Meacham badly wounded. The savages had escaped to their impenetrable fastnesses and could not be pursued.

The whole country was aroused by this brutal massacre; but it was not until the following May that the murderers were brought to justice. At that time Boston Charley gave himself up, and offered to guide the troops to Capt. Jack’s stronghold. This led to the capture of his entire gang, a number of whom were murdered by Oregon volunteers while on their way to trial. The remaining Indians were held as prisoners until July when their trial occurred, which led to the conviction of Capt. Jack, Schonchin, Boston Charley, Hooker Jim, Broncho, alias One-Eyed Jim, and Slotuck, who were sentenced to be hanged. These sentences were approved by the President, save in the case of Slotuck and Broncho whose sentences were commuted to imprisonment for life. The others were executed at Fort Klamath, October 3, 1873.

These closed the Indian troubles for a time in the Northwest, and for several years the borders of civilization remained in peace. They were again involved in a conflict with the savages about the country of the . . .