Excerpts from An Illustrated History of Monroe County, Iowa - 1896

CHAPTER XX ~ THE MINING INDUSTRY.

At the present time [1896] Monroe County ranks third in the list of coal-producing counties in the State; but it is safe to venture the prediction that within the next five years she will occupy a place at the head of the list.

Mahaska County is at present the largest coal-producing county in the State, producing, in 1895, 902,430 tons of coal, valued at the mines at $1,209,256.

Appanoose County came next, with her 350,000 tons, valued at the mines at $420,000.

Monroe County followed, with 313,354 tons, valued at the mines at $391,692.

It should be here stated that the foregoing figures represent the condition of the coal industry at the period of the great financial panic of 1894 and 1895, when all industries, and notably that of mining, were completely paralyzed. During this memorable period of depression the coal industry suffered most of all. The railroads, having little or nothing to haul, did not need coal for steam purposes. The factories throughout the country ran on half or quarter time, and many completely shut their shops. From this source another portion of the coal demand was cut off. The winter was mild and not much coal was required as fuel. Then the coal-miners strike added to the depression and curtailed in a large measure the output in 1895. Hence it is that the figures given do not express the normal condition of the mining industry in Monroe County.

In 1893, just on the eve of the financial crisis, Monroe County produced 641,805 tons of coal.

In 1895 Mahaska County had 28 mines in operation, Appanoose had 72, while Monroe County had but 18, and 6 of this number are but "slopes," or country banks, some employing but one or two men during the winter months.

The State Mine Inspector divides Iowa into three mining districts, and the First District comprises the counties Adams, Appanoose, Davis, Lucas, Monroe, Page, Taylor, Wapello, Warren, and Wayne. Of these, Monroe, Lucas, Wapello, and a part of Davis are the only counties within the First District which yield any coal from the lower coal seam. The others named work a 3-foot vein, with an interval of about 8 inches of fire-clay in the middle of the seam. This 3-foot vein also occurs in Monroe County, but the coal at present is not mined for shipping purposes, and is worked only in country banks, for local consumption as fuel.

In no locality in the mining districts of Iowa is the product of this thin coal vein very suitable for steam purposes. It is lighter, and while it is superior for fuel purposes to that of the lower coal lying at a greater depth, it does not find a market as steam producing coal. Its quality in Monroe County is not quite so good as in Appanoose County, yet this, however, may be due to the fact that up to the present no tests of its quality have been very extensively made in Monroe County, in regions overlaid by a thick rock roof. Where entries have been driven to any considerable distance from surface exposure and beneath thick superincumbent strata of rock or slate, the quality of the coal is perceptibly improved. This coal seam is unvarying in thickness throughout the county, and crops out along all the principal streams. It is preferred for fuel purposes to the lower coal, even in Monroe County, and no doubt it will command a good commercial value in the future, when there is a greater demand for it than now.

About 50 feet below this seam there is another one, about 16 inches in thickness, which is usually from 100 to 150 feet above the lower coal seam. Another seam of about the same thickness occurs above the 3-foot vein in localities within the county.

Monroe County, like Mahaska, occupies the center of the great coal-bearing district of Iowa, which, beginning at Webster County, parallels the Des Moines River on either side, as far down as Van Buren County. This area is classed by geologists as the "lower coal measures." The thickness of these coal measures in Monroe County is variously estimated at from 200 to 400 feet, and contains, as already stated, several seams of coal of varying thickness, from 8 feet down to as many inches.

The lowest stratum of coal is by far the most important commercially, as the vein is of the greatest thickness, and also superior in quality for steam purposes. It does not lie in a continuous or persistent stratum extending over any considerable areas, but occurs in lenticular basins or pockets some of which are of large extent. These pockets doubtless represent the inequalities of surface of the earth, during the glacial period, when the mass of vegetable matter drifted in and formed beds of coal.

When it is remembered that the coal-fields of Monroe County are practically in an undeveloped state at the present time, it is reasonable to conclude that she will soon overtake and outrank Mahaska County as the banner coal county of the State. Much of the available coal supply in Mahaska County has already been mined, and with the present number in mining operations in the county, her output is destined soon to diminish with the exhaustion of her present already thoroughly worked mining camps. A large amount of Monroe County coal lands are held in reserve in anticipation of an early advance in prices incident on the diminution of the coal supply in neighboring localities.

For purposes of State inspection, the coal-producing area of Iowa is divided into three mine-inspection districts. Each of these is under the supervision of a Mine Inspector appointed by the Governor. The First District comprises the counties of Adams, Appanoose, Davis, Lucas, Monroe, Taylor, Wapello, Warren, and Wayne.

The counties of Appanoose, Monroe and Wapello are the only three counties of the district which are of an importance as coal producing counties.

The three named, together with Mahaska County, of the Second District, are the mining centers of the State.

The Second Inspection District of Iowa comprises the counties of Jasper, Jefferson, Keokuk, Mahaska, Scott, and Van Buren, and the Third is made up of the counties of Adair, Boone, Dallas, Greene, Guthrie, Marion, Polk, Story and Webster.

For organization and various other purposes, the mining districts of Iowa, irrespective of the mine-inspection district division, are divided into the Northern, Des Moines, Central, and Southern districts. Some of these districts are known as "low coal" districts, the term "low coal," in mining parlance, meaning coal occurring in shallow seams—the 3-foot vein, for instance, of Appanoose, of the Southern District, or of Boone and Webster of the Northern District.

This "low coal" is distinguished as "mining coal," or coal to mine which the miner has to use his shovel and pick alone. He merely digs the fire-clay from the seam, and wedges or pries the coal out, without resorting to "shooting" or blasting. This coal readily separates from the shale or slate roof, and as it rests on a bed of fire-clay, it freely separates from the latter. In order, however, to mine such coal, the miner has to remove a portion of the upper or lower, or sometimes both upper and lower, adjacent strata, in order to get sufficient height in his room for operating purposes and for the passage of mules drawing the cars. Owing to this extra amount of labor which the miner has to perform, he receives a higher price per ton for the amount of coal mined than if the coal was "higher."

The price per ton for coal mined is fixed by common agreement between operators and miners throughout the coal-mining districts of the United States. This schedule of prices for Iowa was fixed in 1893; and since then occasional violations of that basis led to one of the most extensive strikes or suspensions of labor in the mines that the mining industry in the West has ever experienced. The history of that strike may not be fairly well understood by those not immediately interested, as the causes that led to it were not altogether local in character.

During the eight-hour strike movement of 1890, when most of the various organized labor organizations throughout the United States struck for eight hours of labor instead of ten hours, the United Mine-Workers of America were drawn into the strike movement. The miners did not demand of the operators ten hours' pay for eight hours' work, since the miner is paid by the ton for his labor; but the theory was, that by reducing the number of hours for each day's labor more men could be provided with work in getting out a required amount of coal.

In obedience to an order from the national organization, the Monroe County miners struck; they held out for several weeks, but at some of the mines their demands were not acceded to by the operators, and the strike was abandoned. The movement was not well generated, and, one after another, the camps resumed work without having achieved any advantage.

At the termination of this strike, the Iowa miners withdrew from the national organization, owing to a lack of support, and in 1893 a State organization was perfected, which took the name of the Iowa Miner's Association, with its headquarters at Foster, Iowa. J. T. Clarkson was chosen president of the organization, and Richard Williams, also of Foster, was secretary and treasurer.

That year brought the forerunner of the great financial distress of the country. All departments of trade became stagnated, the arteries of commerce became clogged, and money ceased to circulate freely. Every kind of business succumbed to the general distress. The farmer could not get anything for his products. Transportation shrunk to a minimum, and factories curtailed their output. This, of course, affected the coal trade in a large degree. The operators of mines could not find a market for all their output at former prices. They found that they could not pay operating expenses by paying the schedule rate per ton for mining the coal, and most of the operators began to cut below the schedule rate, which had been fixed in 1893 and which is known as "the 1893 basis." This rate was as follows: For mining coal in the Southern District, comprising the counties of Appanoose and Wayne, $1.00 per ton; Central District, comprising Monroe, Marion, Mahaska, Keokuk, and Wapello counties, 75 cents per ton; Des Moines District, $1.00 per ton; Northern District, comprising Boone and Webster counties, $1.00 per ton.

At the time the general strike or "suspension" was ordered in 1894, by the National United Mine-Workers of America, the Iowa miners were not members of that organization, and were really not parties to the calling of the strike at that time. The order was given to strike on the 21st of April, 1894, and after many urgent appeals from the national officials and from miners within the State, the President of the Iowa Miners' Association issued a call for a miners' convention to meet at Albia on May 3d, for the purpose of considering the appeals from the national organization, for coöperation. After hearing reports from every mining camp within the State, it was found that about two-thirds of the delegates were opposed to a strike or to participating in the "national suspension."

A report was submitted by each delegate, which showed that a reduction had been made, of 20 cents per ton on coal mined in the Southern District, where "low coal" is mined; 25 cents per ton reduction in the Des Moines District, and 20 cents per ton in the Northern field. This reduction affected about 65 per cent of the mines in the State, not including What Cheer and other eastern mines. Several of the Monroe County mines, however, did not make any reduction, among which was the Deep Vein Coal Company at Foster. Yet, notwithstanding, the strike went into effect at that place, the same as if the company had violated the 1893 compact.

In the convention, a motion to suspend work was voted down by one majority. The next day a motion was carried to reconsider the vote, and, when acted on, it was carried by a majority of eleven votes, that, in view of the reductions made in the State, which were threatening to produce a uniform reduction of 20 cents per ton, over the State, by reason of competition compelling the operators who had not so reduced the price per ton for mining to meet the operators in the market who had made the reduction, it was resolved that the president issue a call for all miners in the State to stop work; which was done, and the miners were idle until June 11, 1894, when [an] agreement was entered into by the parties to the contract. . .

Thus ended one of the most extensive and far-reaching strikes that this country has ever seen. It affected at one time fourteen thousand mine employees.

At the convention at Albia, which ordered the Iowa miners to strike, J. T. Clarkson resigned his office of president of the Iowa Miners' Association, but occupied the position of secretary at the time he attended the National Executive Board meeting at Columbus, Ohio, June 4, 1894, when it formally voted to declare the "national suspension" off, and to permit every mining district to make any kind of arrangements they chose between the miners and the operators.

Mr. Clarkson was opposed to the strike from first to last; but, under the overwhelming pressure brought to bear on the Iowa miners, and the persistent entreaties of the miners themselves, he yielded to their wishes, and called the convention. Later he accepted the office of vice-president of the Iowa Miners' Association, but resigned in 1895, and has since then devoted his talent and energy to the practice of law.

Whether this great strike resulted in any material advantage to the miners of Iowa is a matter of doubt. The Deep Vein Coal Company, of Foster, Iowa, refused to enter the agreement, and the strike was prolonged at the place for some weeks. That company had never violated the '93 schedule, and had paid its employees promptly every two weeks. Moreover, it had to face the competition of other mines which operated on a reduced scale for mining, but it gave its men work (though not on full time), as long as they wished to work. Mr. Foster, president of the company, took exceptions to one clause of the agreement requiring his company, on request of the miners, to become their agent in collection of certain dues or "relief funds." The miners at Foster at length signified their willingness to resume work without having secured any concessions from the company, but their action cost the company the loss of some valuable coal contracts, which, on account of its inability to fill them at the time of the strike, were placed with other companies which had already gone to work.

During the strike many of the miners and their families were reduced almost to destitution. The relief fund was inadequate, and the appeals sent out to the farming community for donations fell on unsympathizing ears. The farmers would not contribute to their support, and met the solicitors with the retort: "Why don't you go to work if you are starving? We have to work for whatever we can get, in order to keep the wolf from the door." The farmers could not see the wisdom of a strike at a time when all business was already paralyzed by a financial panic. They felt that they themselves were in the same boat, and refused both material and moral support to the strike movement. Their aid was not withheld through a lack of charity, for they felt that it would be fostering a social evil to encourage men in idleness.

Probably a majority of the sober reflecting miners were opposed to the strike; but in a mining community there are ruling spirits, whose counsels are listened to and heeded by the rank and file. Sometimes these bosses are unscrupulous men, who go by the name of "agitators." There are a few of them in every mining camp, and they are a source of mischief to both operators and miners. In all treaties with operators they are careful to have the latter agree to a clause which binds the operator to not make any discrimination against them and their active followers for having abetted the strike. Notwithstanding the enactment of a statute in the laws of the State, forbidding this discrimination, the "agitator" soon finds himself out of employment in the mines. He goes from mining camp to mining camp seeking work, and is told his services are not desired. He usually goes to work with the rest of the miners, but he invariably lands in some part of the mine where there is bad air, "low coal," or a treacherous roof. He is not a favorite with the "pit-boss," and is assigned by him to the least desirable part of the mine, where he cannot earn a living by his labor.

The scale of wages for mining coal, as agreed to by the joint convention at Oskaloosa, June 9, 1894, which scale was a continuation of the 1893 scale, and was to be in force until April 1, 1895, was not strictly observed by the parties to the contract, and in the spring of 1895 the operators and miners met in convention at Ottumwa, March 29th. In this convention an agreement was entered into, which is known as the "Ottumwa Agreement," and in which it was agreed that the '93 scale would be observed from April 1, 1895, to April 1, 1896. It seems the operators entering into this compact found themselves unable to carry out its provisions, and a reduction was made, which precipitated another strike, by the operators in the Northern, Southern and Des Moines districts refusing to sign or abide by the agreement.

In the Southern District nearly all the men went out on account of a reduction of from 10 to 15 cents per ton. A levy of $1.00 per head was placed on every miner working throughout the districts, but this aid was soon exhausted, and the striking miners were advised by the State organization to temporarily resume work at the reduced schedule price. This advice was given out in a circular signed by J. T. Clarkson, as president pro tem., and Julius Fraum, secretary and treasurer of the Iowa Miners' Association.

In Monroe County the fixed schedule for mining coal has for several years been the same of Mahaska County — viz., 70 cents per ton for summer and 80 cents for winter, or 75 cents on an average. The writer has no knowledge of any rate in Monroe County lower than 70 cents.

State Mine Inspector Report, Monroe County ~ 1895.

| Company/Firm | Superintendent | Post-Office | Type | Plan of Mine | Ventilation | Power | Shipping or Local |

| Wapello Coal Co. | P. H. Walterman | Hiteman | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Smoky Hollow Coal Co. #1 | F. Hynes | Avery | Slope | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Smoky Hollow Coal Co. #2 | F. Hynes | Avery | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Steam | Shipping |

| Deep Vein Coal Co. | C. H. Fugle | Foster | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

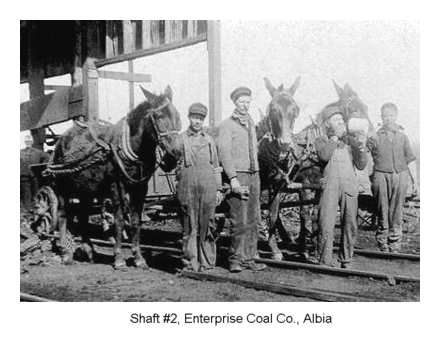

| Enterprise Coal Co. | Thos. Lewis | Albia | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Chicago & Iowa Coal Co. | W. G. Richardson | Cedar M. | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Iowa & Wisconsin Coal Co. | D. H. McMillan | Albia | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| White-breast Fuel Co. #10 | T. J. Phillips | Ottumwa | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Diamond Coal Co. #1 | A. B. Little | Coalfield | Slope | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Diamond Coal Co. #2 | A. B. Little | Coalfield | Shaft | Room & Pillar | Fan | Steam | Shipping |

| Fredrick Coal Co. | Clarence Akers | Fredric | Shaft | Long Wall | Furnace | Steam | Shipping |

| Wilson Coal Co. | P. F. Jackson | Fredric | Shaft | Long Wall | Furnace | Horse | Shipping |

| Remey Bros. | Wm. Remey | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

| W. D. Russell | W. D. Russell | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

| Smiley Bros. | Smiley Bros. | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

| Hartyer Bros. | Hartyer Bros. | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

| John K. Manley | John K. Manley | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

| Geo. Combs | Geo Combs | Albia | Slope | Room & Pillar | Furnace | Horse | Local |

[T]wo more companies have organized and begun operations since 1895 — viz., the Hilton Coal Company, of Hilton, Monroe County, and the Central Coal Company, near Avery.

Few of the mining concerns within [Monroe] county have achieved much success financially within recent years. Labor disturbances have been one cause, and a sharp competition in the coal markets another.

The expense of mining in some of the localities is much greater than elsewhere, owing to unsatisfactory roofing, "faults" in the coal, hilly or uneven condition of the inner surface of the mine, and a variety of other hindrances.

In many cases the railroads themselves have discriminated against certain coal operators, the roads being more or less identified with coal enterprises themselves. Those coal companies which are accorded the special favoritism or patronage of the railroads are successfully operated and those concerned make money.

The fifty days' strike of 1894 was certainly an ill-advised move on the part of the miners of Iowa. They had no local grievances to set right; they struck out of sympathy for a horde of turbulent foreigners working in the mines of the Eastern States—a population consisting largely of Slavs, Huns, and other European nationalities, little governed by civilization or the requirements of good citizenship. The loss to the miners themselves, entailed by the strike of 1894, amounted, in the First District, to 299,584 tons of coal, and $399,226 in earnings, or a decrease of 18.5 per cent of earnings.

Following is a list of accidents occurring in the mines of Monroe County for the two years ending June 30, 1895:

| Date | Name | Cause of Casuality | Company or Firm | Post Office |

| 06 Nov 1893 | Koehler, Julius | Killed by fall of slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 29 Dec 1893 | Kelly, John | Killed by fall of slate | Enterprise Coal Co. | Albia |

| 08 Mar 1894 | Roberts, Robert | Killed by fall of slate | White-breast Fuel Co. | Chisholm |

| 10 May 1894 | McManamon, Thos. | Killed by fall of slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 12 May 1894 | Wignall, John | Fell into shaft, killed | Smoky Hollow Coal Co. | Avery |

| 20 Nov 1894 | Ricker, Chas. | Killed between cars | Smoky Hollow Coal Co. | Avery |

| 27 Nov 1894 | Jones, John A. | Killed by shot | Iowa & Wisc. Coal Co. | Albia |

| 22 Dec 1894 | Bennett, Frank | Killed by powder explosion | Deep Vein Coal Co. | Foster |

| 25 Aug 1893 | Ades, E. T. | Bruised by slate | Deep Vein Coal Co. | Foster |

| 23 Dec 1893 | Wilson, James | Leg broken by fall of rock | Iowa & Wisc. Coal Co. | Albia |

| 16 Feb 1894 | Gustafson, John | Spine injured by slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 17 Feb 1894 | Adolphson, Frank | Leg broken, fall of slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 16 Jul 1894 | Bedman, W. A. | Burned by blown-out shot | White-breast Fuel Co. | Chisholm |

| 16 Jul 1894 | Thomas, Ben | Burned by blown-out shot | White-breast Fuel Co. | Chisholm |

| 18 Jul 1894 | Fleming, Aug. | Right leg broken by slate | Enterprise Coal Co. | Albia |

| 13 Aug 1894 | Kirk, Chas. V. | Back hurt by fall of coal | Enterprise Coal Co. | Albia |

| 16 Oct 1894 | Nicholson, Barry | Burned by pipe igniting powder | Enterprise Coal Co. | Albia |

| 31 Oct 1894 | McKinny, Wm. | Strained hip from fall of coal | Iowa & Wisc. Coal Co. | Albia |

| 31 Oct 1894 | Dyson, James | Burned by blown-out shot | Iowa & Wisc. Coal Co. | Albia |

| 27 Nov 1894 | Taylor, Geo. | Burned by blown-out shot | Iowa & Wisc. Coal Co. | Albia |

| 22 Dec 1894 | Johnson, Victor | Burned by explosion of powder | Deep Vein Coal Co. | Foster |

| 21 Jan 1895 | Polander, O. | Right leg broken by fall of slate | Wapellow Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 04 Feb 1895 | Nelson, Swan | Left leg broken by fall of slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

| 13 Feb 1895 | Bagnell, John | Bruised by fall of slate | Wapello Coal Co. | Hiteman |

At half past 8 o'clock on the morning of November, 1894, a tremendous explosion occurred in the mines of the Iowa and Wisconsin Coal Company, two miles west of Albia. It occurred in what was known as the back entry of the main South. It had been allowed to fall in some time previous, and was now being opened up again by taking a "skip" off the rib. The work had proceeded in this way till at the time of the occurrence it was twenty feet ahead of the last break-through where the air was traveling, and 1,250 feet from the bottom of the shaft.

The explosion was caused primarily by a shot having been fired. The hole for the shot was a 2 1/2 inch hole, and it contained four and one-half common charges of powder. The hole was 6 feet deep, and was 12 inches out of perpendicular. The shot was fired by a squib. Four men sat near the shot, inside the break-through and in the main entry. Two other men were 90 feet distant. These men were burned worse than those in close proximity to the shot. The shot spent its force in the air, blowing out the tamping without breaking up the coal. The flame from the shot seemed to ignite in the air of the entry either an accumulation of gas or "dust."

In this explosion John A. Jones was killed and James Dyson and George Taylor were severely burned and maimed for life.

The exact cause of the explosion was somewhat of a mystery to mining experts.

Click on "back button" to return to this webpage.

Wapello Coal Works, Albia |

Wapello Coal Co., Hiteman |

#18, Buxton |

Deep Vein Coal Co., Foster |

Coal Mine, Monroe Co. |

Shaft #10, Buxton, 1908 |

Transcriptions by Sharon R. Becker, September of 2010