Excerpts from An Illustrated History of Monroe County, Iowa - 1896

CHAPTER XIII ~ EARLY JOYS and SORROWS.

While the early settlers had to encounter many hardships, there were still a few threads of gold running in the woof and warp of their pioneer lives. Their cheeks were aglow with health, their hopes were strong, and their hearts were light.

There were no social barriers excluding the poor from the rich; all were poor in this world's goods, yet all enjoyed a wealth of honor, social equality, and contentment. Sometimes the meal-chest became empty, and before Haymaker's mill had been built on Cedar Creek, a domestic strait of this kind entailed considerable inconvenience on the settler. A milling trip required from a week's to three week's time. Sometimes the settler had to "wait his turn" for several days. When this was the case, he slept in the mill at night, or used his own wagon as a sleeping apartment. He also took along provisions for several days, and if these became exhausted, he had his rifle and fishing tackle with which to solve the dilemma. The mills were located at Bentonsport, Keosauqua, or sometimes the settler had to go as far as Burlington.

When there were deep snows or impassable roads, everybody ran out of bread-stuff and had to either live on boiled corn or else take their corn to the home of the writer's grandfather, Thomas Hickenlooper, who lived where the town of Foster now stands, and grind their grist on a hand-mill something similar to the spice-mills now seen in grocery stores. It was operated by a crank, and contained a fly-wheel about two feet in diameter. Grinding on this mill was laborious work, and, like the mills of the gods, ground slowly; but not exceedingly fine, like the latter, for the buhrs were dull. The remains of the old mill are still lying about the old Hickenlooper homestead.

It may seem strange to state that during the first few years of the county's settlement water was scarce. The settlers either did not know where to dig for or else there was none on the flat, high, prairie regions. Old settlers still claim that there was but little living water in the ground until after the soil had been broken and cultivated for several seasons. It all drained off into streams, the virgin sod shedding it without absorbing it. Nobody ever thought of constructing ponds or reservoirs.

The prairie-itch was another pioneer luxury which the people of the present generation do not enjoy. It usually entered on a seven-years lease with the latter, but at the end of that period the lessee was seldom evicted from the premises. It ran through families, and many well regulated families were never without it. It was a sort of heirloom in those families. It is generally understood that the itch is fostered by habits of filth and unwholesome neglect of the bodily condition, thus inviting a small animal parasite to burrow near the surface of the skin, subsisting on the impurities of the blood. It is hard, however, to account for the greater prevalence of the disease in early days unless it may be referred to the fact that in those days of scarcity of clothing many people were obliged to wear a single suit for a great length of time without change or washing. This, of course, rendered the skin impure, and made it possible for the parasite to seize a foothold.

The Charivari.

In 1847 there were but four families in the village of Albia. Two of these families occupied the little log courthouse — viz., the Flints and the Marcks. Dr. Flint had two charming daughters — Amy and Nancy. Jonas Wescoatt won the heart of Amy, and Robert Meek, who for many years since was one of the proprietors of the well-known woolen mills of Bonaparte, Iowa, wooed the equally charming Nancy. The wedding was to be a double affair, and special efforts were taken by the contracting parties to evade the inevitable charivari.

On the 10th of October the wedding day was arranged, and Mr. Meek drove over in a spring-wagon, and the plan was to drive to Eddyville immediately after the ceremony and escape the serenading crowd. During the evening of the 9th the boys "got wind" of the affair on the morrow, and of the plans to escape; so they took off one of the wagon wheels and concealed it. No trace of the wheel could be found, and the bridal parties were thrown into great consternation. When the hour fixed for the marriage arrived, the justice made his appearance on time, but the bridal quartet was conspicuously absent. The assembled crowd of boys grew uproarious in their glee, for the thought the wedding had been postponed. The justice, however, had been notified to return home and reappear in the evening and tie the knot secretly. He did so, and the newly coupled quartet repaired to the cottage of Mr. Wescoatt to spend the night.

In the meantime, however, when Mr. Michael Lower, the justice, reappeared, he was followed by a spy, who saw the nuptial proceedings and communicated the fact to the crowd. Late at night they stormed the Wescoatt stronghold and forced the garrison to capitulate. The charivari was a great success, and each bride was compelled to present herself to receive the blessing of the crowd.

In the morning the missing wheel was found by the side of the wagon.

An Interesting Find.

One fall, in the '50s, Dr. Gutch, then a young medical student, was teaching school near where Maxon now stands. One day, during the noon hour, he and the school-boys were out on the hillsides, gathering hazel-nuts. They saw a strange object some distance away, near the roadside. Some thought it a deer, others a mad dog having a fit. They crept cautiously up to it to investigate, and they finally discovered that it was a man. They approached the apparently lifeless form, and discovered it to be that of Joe McMullen. Gutch examined his pulse, and then remarked: "Damned if he ain't alive!" They carried him to a hay-stack near by, and in due time he became conscious, and returned home. He had just made a horse-trade with Jesse Snodgrass, and had gotten $15 to boot. He had considered it a good trade; and to get the better of Jesse Snodgrass, in a horse-trade was an achievement worthy of celebrating by taking a drink at Harrow's grocery. He had taken a little too much, and on his return home had become "becalmed."

Bee-Hunting.

The early settlers found the forests alive with wild honey-bees. Almost anyone could find a bee-tree by strolling through the woods and examining every knot-hole in the trees; but the professional bee-hunter had a more methodical way of locating the hive. The honey-bee, as everyone knows, flies straight, or in a "bee-line," to its home, when laden with honey, and in order to get the exact bearings of the bee-tree, the hunter took the "course" of the homing-bee. There were several ways of securing these observations. One way was for the hunter to lie down flat on the ground in the midst of a growth of wild flowers, and as the bee which came to work on the blossoms took its departure, the falcon-eyed bee-hunter got its "course" and followed it up. Sometimes the distance would be a mile or more.

It is said that when the bee-hunter became old and dim of eyesight, he seized the bee, and, removing its sting, thrust in its place a tiny white feather, and then released the insect. In its flight homeward he could follow with his eye the white feather for a long distance. This, however, is perhaps a popular vagarism.

Another method was to attract the bee to a certain locality by means of "bait." This bait consisted of a pair of corn-cobs placed in a fruit can and saturated with a saline fluid always available. The bees would gather in large numbers, and the hunter, lying on his stomach underneath the suspended "bait," got his "courses."

Another method was to go into the forest and burn honeycomb, when the scent of the burning would attract the bees.

Sometimes a bee-tree would yield as high as several hundred pounds of honey, and the hunter's accumulation of sweets was usually stored in "dug-outs," or large troughs made of cottonwood logs.

Among the writer's earliest recollections are several of these old "dug-outs" stored in his grandfather's smoke-house. They had at first been used to hold honey, then, later, as receptacles for containing pork; and, within the writer's recollection, held soft soap. Barrels were not so plentiful as now, and it was an easy task to hollow out a large log of soft wood to take their place.

Bee-trees are still frequently found in the woods, but the hives do not thrive, and seldom live through the winter. The bees are from tame colonies, and they do not seem to adapt themselves to habitations in trees.

The Log-Cabin.

The nearest approach to a "house not made with hands" was the log-shanty of the "squatter." The logs did not so much as have the bark removed, and the floor, at least, was made by the Supreme Architect of the universe, for it consisted of the bare ground. The chimney was made of sticks and mud, and the roof was formed of clapboards, or, not unfrequently, of layers of slough-grass.

This dwelling was but a temporary structure, and as soon as the "squatter" made up his mind to take a claim, he set about to erect a more elaborate building. He cut the finest white oak logs which he could find in the forest, hewed them perfectly square and smooth, and with his ox-team hauled them to his building-site. Then he invited the entire community to the "house-raising." This was a tremendous social affair. The neighboring housewives, for a radius of ten or twelve miles, came in and helped bake pumpkin pie, or brought them with other victuals already cooked. The young ladies came too, but, as they were "dressed up" in their "hoops," they merely "set around," or helped wait on the tables.

In the crowd there were always men who were locally famous as good "cornermen" — i.e., men who could carry up the corner of a log-house with more skill than others. One of these was selected for each of the four corners, and, as might be supposed, each vied with the other in a contest of skill. When the writer's grandfather's house was erected, the prospective occupant of the structure offered a premium of a bushel of potatoes to the "cornermen" doing the best job. Allan White bore off the prize, though Lewis Arnold came in as a close second.

This house was built in 1848 or 1850, and was a large two-story. It was then sided with lumber hauled form "the river" and was skirted with two verandas and all painted white. It was one of the largest edifices in the neighborhood, and its owner, in consequence of a kind of baronial homage, accorded to him by his neighbors through a veneration for the size of the house and the number of chimneys, elected him "squire," and his son Charles constable, which emoluments they shared for several years. The house is still standing, and when remodeled, a few months ago, the hugh square logs were found to be as firm and solid as when they were placed in position nearly forty years ago; but the "cornermen" are all long since dead.

When a house was raised, and the "puncheon" floor laid, the festivities were concluded by a big dance, or "ball," as the eminently respectable tone of the pioneer dance was entitled to be termed. It was a thoroughly cultivated and respectable affair, and was very different from many of the public dances of the present day.

The "Hoedown."

Such is the name commonly applied to the free-for-all public dance. While those who participate in the "hoe-down" are by no means rude or scantily civilized, yet at the public dance-house they come in contact, and for the time being, at least, are placed on the same social level, with persons of both sexes whom they would not recognize on the street or in the home.

At the common "hoedown" those French terms used by the man who "calls off" are Anglicized into plain English; for instance, the caller will shout the familiar term "Chassez partners!" but in the "hoedown" whirl it s translated into:

"Swing your taw,

Everybody dance to please Grandpa!"

Another term is indicated thus:

"Crow hop out and bird hop in,

All fine flippers and swing 'em agin!"

Or, if the gentleman is directed to swing to the right and the lady to the left, the man who "calls off" shouts from his elevated position on the inverted barrel:

"Jay-bird to the right, yellow-hammer to the left!"

Taken as a whole, the "hoedown" has its legitimate place in society, and ought not to be too harshly criticized.

Camp-Meetings and Water-Melons.

Unhappily, the old-fashioned Methodist camp-meeting is a joy of the past. The church edifice has long since gathered the people away from "God's first temples" and encompassed them by frescoed walls and vaulted ceilings. Instead of "Coronation," "Antioch," and "Old Hundred" rolling out upon the assemblage of rich and poor alike in a flood of harmony, awakening a spiritual warmth in every heart, the fashionable church walls re-echo the superb strains of some lofty anthem, which, while sung by a trained choir, accompanied by violin, cornet, and pipe organ, yet fails to find a responsive chord in every heart.

The aged sister, old-fashioned in both her ways and her garb, likes to go where she can try to sing, even though she cannot "carry a tune." At the old-time camp-meeting she could both exercise her discordant voice and wear her plain bonnet and calico gown without being stared at.

The meeting was conducted under the foliage of some grove, or sometimes beneath a great tent. Those who attended from a distance lived in tents pitched on the grounds, where they cooked their meals and slept at night on straw-beds. The camp-meeting was usually held in September, and the water-melon was the fruit offering and the fried chickens the burnt offering at this sacred tabernacle.

Of later years, the modern "holiness" offshoot of the United Brethren Church, and a kindred organization splitting off from the Methodist and other churches, and taking the name of "Friends," have each revived the old-time camp-meeting to some extent. They hold periodical sessions in camps, and in their devotional practices are distinguished by a fervor in some cases amounting to a frenzy. At times the subject lies in a cataleptic state for hours, unconscious of surroundings.

The "Hardshell" or Missionary Baptist preachers of early days approached nearest to the ideal conception of John the Baptist of any of the champions of Christ. While they did not subsist on locusts, they may have begirted themselves with leathern girdles. At any rate, they were usually of a migratory species of divine, ranging up and down the streams and holding revivals in the little school-houses. They scorned to preach for money and always guaranteed salvation "without money and without price-ah." They affixed the syllable "ah" to the end of every sentence as a sort of declamatory balance-wheel to regulate the inflections of their voices. They were good men in any capacity, but they had a particular aversion to high-toned churches, and to preachers who wore "biled" shirts and paper collars.

The writer remembers old Brother Jackson, who used to "labor" down on Soap Creek. "Brethren and sisturn," he used to say, "I ain't one of them big guns who preaches in the great cities like Centerville and Moravia and Albia and Ottumwa-ah, but hit's always been my lot to preach in the dark corners of the earth-ah, whar the pot biles the slowest and the purse is the lightest-ah!"

Brother Jackson's dramatic illustration of the sinner's imminent danger of hell-fire was clothed in all the fervent imagery of Dante's "Inferno." "And now, dyin' sinner-ah, you are hangin' by a cord to a limb that bends over the lake of fire and brimestone-ah. The blue blazes of etarnal hell-fire have about burned the limb in two. It bends, it crackles as its wood is roasted, and your body settles further down into the lake! Then the cord takes fire, and is burnin' in two-ah, and that is how you are hangin' to-night-ah. Your thread of life is about burned in two, and your soul is settin' down in the lake of unquenchable fire-ah."

Jim Pollard, when at the flood-tide of his spiritual zeal, was a power in the land. When he ascended the pulpit, he invariably removed his coat, and later on, as he warmed up, threw off his vest, and by this time the sermon began to assume a funnel-shaped form, and those of the congregation nearest the pulpit began to scamper for back seats.

One Sunday morning, while mowing slough-grass in the Soap Creek bottom, the Lord came to him in a vision and recommended that he mend his ways. [Jim] said: "As I swung the scythe to and fro, the stubbles would strike against it, and the scythe would say: 'Go to meetin', Jim! go to meetin', Jim!' Then when I would whet the blade, the scythe-stone would say, as it struck it on either side: 'Go quick, go long! go quick, go long!' "

On another occasion Brother Pollard called at the home of Dr. Arnold in Urbana Township, while the family were at breakfast. They had boiled cabbage, and Jim was specially fond of boiled cabbage. "Won't you sit up and take breakfast with us?" asked Mrs. Arnold. "Ah, no!" was his reply, as he looked wistfully at the dish of cabbage; "I am too full of the love of God to hold cabbage!" He had just returned from a revival.

On another occasion he had just returned from a preaching tour in Missouri, and had received a call to preach at the school-house at Albany. He began his discourse with this exordium: "Brethren and sisters, Jonah was puked out of the whale to go and preach to the people of Ninevah, and I have just been puked out of Missouri to preach to you-uns!"

Embryo Villages.

There are numerous sites of former villages in Monroe County, which, like Goldsmith's "Sweet Auburn," have vanished, save now and then a garden flower to mark the spot "where once the garden smiled." In the spring and summer of 1856 immigration was at its flood-tide. In every neighborhood a village was laid out, the interests of which were boomed by the projector of the town. There were no railroads in the county at that time, and no one locality had any advantage over its rival in the matter of location. In time, however, most of these hamlets died down from the effect of the natural law of a survival of the fittest.

In the summer of 1856 the village of Fairview, or Cuba, as it was subsequently named, was laid out in Mantua Township. The place exists to-day only in name, and is a few miles east of the town of Avery. At one time it was a promising village, but the CB & Q Railroad passed north of it, and the town of Avery killed it.

Eldorado, in Cedar Township, was also started and looked promising on paper. It boasted two houses.

Smithsfield and Hollidaysburg were also candidates for municipial (sic) greatness, but soon shared a like fate.

Pleasant Corners, in Pleasant Township, situated about a mile north of the present village of Frederic, was once a lively village. It had a store, blacksmith shop, and a "Seceder" church. To-day it is one of the loveliest spots in the county, but it has ceased to be a village.

Urbana City was started about the same time. It was once a flourishing village, and was the seat of Soap Creek civilization and commerce. It contained a flouring mill, school-house, blacksmith shop, two stores, a shingle-splitter, and a saloon. To-day it is a corn-field.

Along about the year 1890, Frank Fritchle laid out the town of Minerstown, a half-mile west of the present town of Foster, in Monroe Township. The town was regularly surveyed and platted, and was intended as a rival of Foster, just starting. There was but one house erected in the town, but the streets and avenues remain on paper, and are well preserved.

Selection is a post-office five miles south of Albia on the Centerville, Moravia & Albia Railway. Some years ago it boasted of a water-tank and general store, but it never grew, and while there is still a store at the place, the tank has been removed, and the railway station building has been locked up for years, there being no agent at the place.

The "Water-Witch."

Necessity is said to be the mother of invention, and as water is one of the necessities of life, it may also be stated that it is the maternal relative to the "water-witch." If this mystical personage may also be permitted to claim a paternal progenitor, we will say that Ignorance is the father of the "water-witch." When the country was new, water, as we have already stated, was often scarce, or difficult to locate in veins in the earth. Then, like a Moses smiting the rock with his rod, the "water-witch" arose with his "divining-rod," to tell people where to dig. Professors of this occult science usually selected some fruit-bearing twig—a forked switch, each prong a foot or more in length. He grasped each prong in the hand and walked around with the switch pointing in front. In passing immediately over a spring in the earth the stick would point downward, according to popular belief. The switch, in the hands of a right good "witch," would be so persistent in its efforts to point downward that it is claimed that in grasping it tightly the "witch's" grip would sometimes rub off the bark from the twig, or even break it. A good "witch" could always tell how far down the water might be found. The "divining-rod" was a little capricious in its action. It would not point down if actually held over a pond of water, or water in plain view. It was a way it had of doing, and the witch did not make any efforts to explain the seeming contradictory phenomenon.

Schools and School-Teachers.

The first school-house erected in the county was built in Pleasant Township in 1844. It was known as the Pleasant School, and later, the surrounding township was named Pleasant Township in honor of the little school-house. It stood on the Gray farm, and Lorania Adams, of Blakesburg, was the first teacher. Dudley C. Barber was the next teacher, and taught the winter term of 1844.

In the early '50s Hon. T. B. Perry, our present State senator, taught a school in the village of Albia. At that time there was no school-building and the school was conducted in the little frame M. E. Church building. Some years later, Mrs. M. A. R. Cousins taught a select school in Albia. Mr. March was also a successful teacher in the early days of Albia, but these private schools of course afforded but meager facilities for educating the children, and Professor George instituted the Albia High School, which he conducted for a long time.

In 1863 the population of the Albia School district became so large that the Christian and Baptist church was rented

for school purposes. The next year the School Board levied a 5-mill tax and bought the dwelling-house of W. C. Hatton,

which faces the Commercial Hotel on the west, and which is now occupied by Mr. Wm. Peppers.

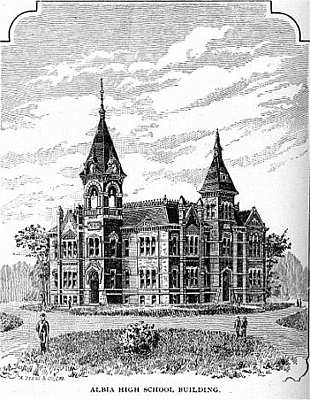

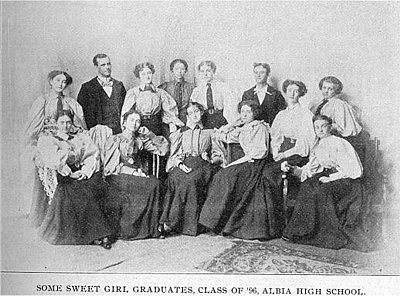

In 1868 the independent district of Albia erected a three-story brick building on the site where the magnificent High School building of to-day stands. It cost $28,000, but in 1878 it was destroyed by fire. The present structure was built in 1879 at a cost of about $30,000, which price is remarkably low for the dimensions and character of the edifice. It is one of the best school edifices in southern Iowa, and the Albia High School ranks among the first of any in the State for educational success. Its graduates are eligible to entrance into the State University.

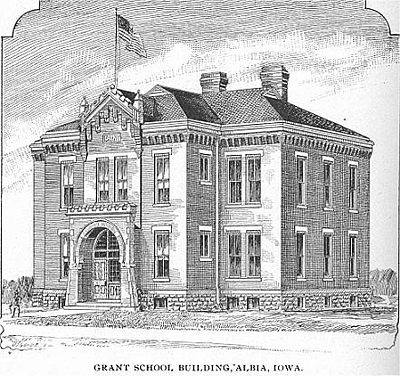

In 1894 the Grant School building was erected in the South Park addition to Albia. It is a handsome three-story brick, designed to accommodate the lower grades of the High School. It cost $10,000.

The principal of the High School holds his term of office for three years. Professor Hollingsworth is the present incumbent. His staff of assistants for the school-term just closed consists of Miss Martha McQuade, 1st assistant; Mrs. L. B. Carlisle, 2nd assistant; Mrs. H. G. Hickenlooper, 8th grade; Mr. Albert Ewers, 7th grade; Miss Alice White, 6th grade, Miss Myrtle Harlow, 5th grade, consolidated; Miss Maggie Harlow, 4th grade; Miss Orphia Rigdon, 3rd grade; Mrs. O'Bryan, 2nd grade and primary grade. Miss Myrtle Harlow's department was transferred to the Grant School.

The teachers of the Grant School were: Mr. L. Bay, 7th and 8th grades; Miss Myrtle Harlow, 5th and 6th grades; Miss Laura Dashiell, 4th and 5th grades; Miss Daisy Sales, primary grade.

The old-time pedagogue is a creature of the past. He is a genus now well-nigh extinct, and the very agent which it was his mission to promote has tended to his own extinction. He was a creature of meager education and not unfrequently of a low order of intellect. In some cases, however, the old-fashioned school-master was fairly educated for the times, and he was usually the best informed man in the neighborhood. He could read, write and "cipher," and that was about the whole range of learning in those days. If the pupil passed beyond these, he was looked upon with suspicion. He was acquiring too much "book-larnin," which, in the estimation of the pioneer "fogy," was a certain precursor of moral ruin. The schoolmaster's local reputation of being a savant rested on his profound knowledge of mathematics, and whenever two farmers got into a dispute as to whether a hilly row of corn contained more corn-hills than a level one, reasoning from the analogous assumption that a serpentine line, if drawn taut, would thereby be increased in length, they referred the problem to the school-master, from whose unbiased and dispassionate decision there was no appeal.

Algebra was not taught in the common branches at that day, but there was rule in arithmetic, known as "Position," which in some measure supplied the place of an algebraic equation, in certain problems. The rule consisted in assuming any number as a basis of calculation, and then, as one would be found to exceed the number to be ascertained, and the other less than that number, their relative relation to the given number would be noted and the required number found. The rule was, as the total errors are to the given sum, so is the supposed number to the true one required. There was "Single Position" and "Double Position." The rule for "Double Position" was to place each error against its respective position, multiply them cross-wise, and if the errors were alike—that is, both greater or less than the given number—divide the difference of the products by the difference of the errors, and the quotient was the answer; but if the errors were unlike, the sum of the products should be divided by the sum of the errors.

But the "Rule of Three" was the repository of the school-master's mathematical genius. There was the "Rule of Three Direct" and the "Rule of Three Inverse," the "Single Rule of Three" and the "Double Rule of Three." This rule and that of "Position" were obsolete, however, within the history of Monroe County.

Then came "Vulgar Fractions," and then "Exchange," which latter was very voluminous.

In later years, when Joseph Ray introduced his mathematics in text form, his "Third Part" was the arithmetic in which the student found himself hopelessly engulfed in the intricacies of mathematics. The first snag he ran up against was a "sum" called "John Jones' Estate." Here he usually turned back to "review"; but if he succeeded in crossing this mathematical Rubicon, he forged on until he ran head-long into the "dirty page." The "dirty page" contained some miscellaneous problems which were intended to be solved by analysis. This page wore out long before the other pages, notwithstanding the constant use of the "thumb-paper." It was called the "dirty page" because it was soiled by long occupancy by the student.

The student, when he reached about his nineteenth year, quit school; but he usually discontinued school in summer several years earlier.

In the primitive school-houses the writing-desk was the most conspicuous fixture next to the "master" himself. this desk was arranged all around one side of the room, and was constructed of planks about a foot in width. This desk the boys industriously carved with their jack-knives until every inch of the surface bore the handiwork of some youngster who afterwards carved his name in the roster of citizenship, if not in the niche of fame.

The "master" set the copies for the pupils, writing with a pen made from a goose-quill. There was no system of penmanship then in vogue, and the pupil merely imitated the handwriting of the "master," whether it was good or bad. If it was not quite "Spencerian" in elegance or legibility, it usually inculcated a moral precept, such as "A studious boy will learn his lessons well," or "Moments of time are like grains of gold," etc. The boy squared his elbows, grasped his pen with the firm grip of a mariner upon his oar when pulling his surf-boat through a heavy sea, then he lowered his head until his eye was on a level with his desk, and, glancing alternately at the copy and the point of his pen, proceeded to imitate the handwriting, using his tongue as a sort of lever to regulate the strokes of the pen. After constructing a few words of the copy, he would prod his neighbor with the point of his pen, or carve a few cuneiform characters on the desk with his knife, as an abstraction from the strain on his mental powers.

Grammar was also taught, but with indifferent success.

Spelling was the chief occupation of the school-room, and the pupil learned to spell by conning over long columns of words in Webster's blue-backed speller. This speller contained two illustrated narratives, which were intended to convey to the youthful mind an indelible example of honesty. The tragic fate of old dog Tray was set forth as a warning to those who go in bad company. There was also a picture of the bad boy up the farmer's apple-tree. The farmer first asked him in a gentlemanly way to come down; he declined, and then the farmer began to pelt him with turf; still he staid (sic) up the tree; then the farmer, seeing that kind words and turf were useless arguments, concluded to see what virtue there was in stones. Another episode, involving the principle of equity, was that of the farmer's bull that gored his neighbor's ox.

After Webster's speller came McGuffey's spelling book. It contained a more thorough treatise on the science of orthography, and had "dictation exercises," showing the application of synonyms of the English language. Its main feature, however, was its long columns of words.

The writer at one time enjoyed the distinction of being one of the "crack" spellers of the district. At this time the spelling-school was at the zenith of its popularity. The spelling-school would be announced about a week before the night set. Then a challenge would be sent to a neighboring district. The recipient of the challenge would marshal the best spellers of the school, and all would be on hand at the appointed place. Two persons—usually a young man and his best girl—would "choose up." Then, after the seats had all been arranged around the walls, the teacher or person whose duty it was to "give out" would have the two choosing parties "guess the page," and that one making the closest guess would have the first choice of spellers in the crowd; the other party then made the second choice, and the "choosing" went on alternately until all were selected on the two sides. The next thing to decide was whether to "stand up and spell down" or to "send runners." One plan was usually adopted before recess and the other after. Invariably the former plan was adopted after recess, and then came the tug of war, when all had "missed" words and taken their seats except the champion spellers. They held their ground for a long time, but one by one would go down, usually on some trifling word "missed" by mere inattention on the part of the student "missing" it. Then the teacher would turn back to "chamois"; "chamois" was at the head of a long column of words of mixed phonetic character, and the whole page was considered the hardest of any spell in the book. When "chamois" would be "given out," the partisans of the respective sides would cheer, and listen with bated breath when the teacher got down to "daguerreotype," because this word was one of the hardest to spell of all. Finally all would go down except two, representing the rival schools. They would hold the floor sometimes for an hour, and sometimes it would result in a drawn battle, neither party missing a word.

Of late years a radical change in the method of teaching orthography has been adopted, and the dear old spelling-school of hallowed school-days memory has become an institution of the past. Even to this day, the recollection of the spelling-school somewhat softens the harsh outlines of our otherwise austere disposition, as the vision arises of the freckle-nosed school-girl with whom we used to "choose up." Her flaxen hair was split at the ends, and stood out behind her ears like a ram's horns, and yet we felt, when sitting by her side, a good deal like one is supposed to feel when sitting beside the throne of grace. She could not spell "putty," yet we always chose her first, so we could sit next to her and whisper to her how to spell her words. The spelling-school was one of the redeeming features of an otherwise imperfect system of instruction, and since it has grown obsolete, the general knowledge of correct spelling has suffered materially.

The popular school-games were "black-man" and "town-ball." "Black-man was played by both girls and boys. Some one would be "black-man" bases would be planted a few rods apart, and the "black-man" would charge down on the school, who would make a run for the opposite base. If the "black-man" succeeded in catching anyone, the latter would become one of the "black-man's" imps, and would help catch the others, until all were caught but the big, rough, overgrown school-boy; to take him was a difficult task, as not more than one could succeed in getting hold of him at one time. It was a delicious experience to have one's school-mate sweetheart catch him; then the youth would struggle, seemingly to free himself, but really to necessitate the girl putting her arms around him to hold him, and expedient which she invariably found highly necessary. She, in turn, would seldom make much effort to escape her "black-man" beau. It was a great game for the promotion of school-day courtship, or "puppy-love"—a malady with which we have all been afflicted at some time or other.

"Town-ball" was the antecedent of the modern popular ply of "base-ball." "Two-corned cat" was another game of ball, in which but four boys participated in a game.

The teacher in those days usually "boarded round," and it was the custom on the arrival of Christmas to bar out the teacher. On the day before Christmas the teacher would arrive at the school-house in the morning to find the door and windows barricaded. The big boys would be inside, and "terms of surrender" would be written on a piece of paper and slipped out to the teacher. This document usually specified a treat of a bushel of apples, candy, or, in the ruder settlements, whisky. The teacher invariably demurred, and stormed and railed in sometimes real and sometimes affected rage, and if he did not supply the treat, or make a promise to do so, he was often seized by the crowd and carried bodily to some neighboring creek and threatened with a "ducking" through a hole cut in the ice. Sometimes the teacher climbed to the roof and placed a board over the chimney, forcing the smoke into the room filled with pupils. Then the boys would have to drown out the fire if they had water, and if not, their victory was lost.

In the year 1847 or 1848 a tall, lank Yankee came into a district in Urbana Township. He was from away down east, and was well dressed, and "put on airs." His style of dress so astonished the peaceable denizens of Soap Creek that the new-comer not only became an object of curiosity, but of unenviable criticism as well. One day he went to the local "swimmin'-hole" on Soap Creek to wash. Some mischievous boys stole his clothes and the young man was in desperate straits. He crept through the forest, until he arrived near a dwelling, when he called for the men folks to bring him some clothing. The men were not at home, but four big hounds responded, and, seeing the fugitive naked, mistook him for some big game, and gave chase. The young man climbed a tree, and as the hounds bayed "treed," two young ladies heard the well-known notes of the hounds and hastened to ascertain what they had "treed." After discovering the game, they beat a hasty retreat and apprised the men folks of the situation, when the latter brought some clothing and released the young man, who soon left the country, overcome with mortification.

Soap Creek Jurisprudence.

The region drained by the classical Soap Creek was always a fruitful locality for the lawyer. These barristers of bygone days were not as profound in legal lore as some of the expounders of Blackstone of to-day, but they were usually equal to any occasion on which their talent and oratory might be called into requisition.

Every time the stream itself would overflow its banks, a half-dozen law-suits would be among the evil results of the flood. One settler's fence-rails would be swept away and be lodged on the land of his neighbor farther down the steam. The latter would seize them and claim them as his own. If the dispute could not be settled by the amicable arbitament of a big fight, a law-suit was the inevitable result. Innumerable important rulings have been made from time to time by "his Honor," the justice of the peace, involving the rights of property, and the views taken by the various justices in summing up the evidence in the matter concerning the ownership of the rails have bee rather kaleidoscopic.

Our old friend, Samuel G. Finney, who resides near Blakesburg for some years past, has usually been retained in cases of a civil nature; and R. B. Arnold is usually on one side or the other, also.

If it is a criminal case, Bill Kinser is much sought for by the defense, and usually brings his client out unscathed. His manner before the magistrate or jury is vehement, and if his case is a hopeless one in which ordinary construction of the law would be unavailing, he usually succeeds in impressing the court by means of superabundance of stupendous oratory. He would not hesitate to engage in a legal duel with the Chief Justice of the United States on a disputed legal point, and if before a court of his own vicinity, would carry off the prize.

Bill Knapp and Levi Woods are another strong brace of local attorneys. Knapp's legal success is somewhat hampered by conscientious scruples, as he is of a religious turn, and preaches occasionally. Wood's efforts in the legal profession are unfettered by influences of a similar nature, and his opportunities have full swing.

Adam Hopkins settled on Soap Creek in about the year 1845. He could read and write, and served as justice of the peace for a number of years. His son Perry was usually elected constable. Uncle Adam knew very little about the law, but he had one special merit; he carried out the interpretation of it to the letter. In one of his law-books — a sort of "Justice's Guide" — was a blank form for rendering judgments, and, as an example, the costs were inserted in the proper space as $3.50. So whenever it became his duty to issue judgment, he always made the cost $3.50, as if this amount were a fixed sum prescribed by the law, like a marriage license fee or a poll-tax. This was, of course, divided between himself and son Perry. When witnesses demanded their fees, Hopkins informed them that $3.50 was the maximum limit of costs allowed by law, and that if they expected fees, they would have to look to the party who had them subpœnaed.

Hopkins always fined a man for fighting, but occasionally indulged in the same diversion himself. He and Eleven Dean got into a fight, and Dean was getting the better of him, when Hopkin's son Perry, by virtue of his official capacity as constable, rushed in and struck Dean a blow over the head with a billet of wood, at the same time exclaiming in a loud and official tone of voice: "I command the peace in the name of the State of Iowa." Hopkins regained his feet, and, seizing a club, dared Dean or any of his friends to "come on." Dr. Udell sewed up the opened scalps, and peace once more brooded over the temple of Justice.

In 1850, during the horse-thief period, Squire Harris was justice of the peace. One day a stranger rode up and swore out a warrant for a man who, he alleged, had stolen a horse. Wile Harris was issuing the warrant, another stranger rode up to the cabin, and arrested the first man. The latter was riding a stolen horse, and was attempting to work a "blind," to shield himself.

Some Pioneer Episodes.

In early times, the forests, as we have stated already, swarmed with wild bees, and whenever the hunter found a "bee-tree," he carved his initials on the tree, which evidence of ownership was universally recognized and respected.

Old Ben Ashbury, who ran the blacksmith shop in Urbana Township, accused Newt Van Cleve of cutting a marked bee-tree, and, as it was looked upon as a most heinous offense, Newt very naturally resented the charge. Bad blood sprang up between the two, and as old Ben had the reputation of being a "good man," and as young Van Cleve had his honor to vindicate, it was looked upon as inevitable result that the two would be bound to meet, and that when this inevitable result occurred, it would be as the meeting of two fierce tides—Greek would meet Greek, when the conflict came. One day Van Cleve was passing the blacksmith shop. Old Ben came to the door, evidently spoiling for a fight. He accosted Newt with mock suavity. With an affected softness of manner, indicated by a courtly bow and swing of the hand, he addressed him: "How do you do, Newton, and how are you prospering in the beautiful land of milk and honey?" The allusion to honey seemed to have a sting in it, and Newt told him it was none of his "d—d business." Then they went at it. Newt, like young David of old, carried a stone, and with it struck the Goliath-like Ben on the head, knocking him senseless. He thought he had killed him. He raised his head and wet his face with water from the slack-tub, and then, procuring some help, carried his victim into the house, where he attended him with the utmost care until he revived. When Ben returned to consciousness and found the young man attending him, it challenged his admiration and gratitude, and ever after they were warm friends.

Ashbury is said to have been a man of many good traits and good intelligence, but he had a violent temper and loved to fight. On another occasion he and a man named Meeks struck up a fight in Blakesburg over politics. Meeks was a Southern sympathizer, or, at least, a Buchanan Democrat. Ashbury was an abolitionist, and struck Meeks with a handsaw, and came near cutting his throat. He then got Meeks down and pulled his hair.

On still another occasion some wild boys, in passing his house, annoyed him by calling out: "Hello, old Bogus! come out here!" [Bogus was the name the boys gave him.] Some days later, on meeting the boys, old Ben reproved a young Grimes for his conduct. Grimes denied having been one of the disturbing party, and Ben struck him with a carpenter's square, which came near killing him. Ashbury was arrested and taken before Squire Hiram Hough. Hough had just been elected justice, and was not familiar with the wording of an action for assault and battery; so, after making several efforts, he gave up the attempt with the excuse that he wished to go to mill. The case was then taken before Thomas Hickenlooper. The aborted information drawn by Hough showed that the defendant had been brought before him on a charge of "psalt and battery." It was a great day in Squire Hickenlooper's court. The whole country gathered in, and took both dinner and supper with the unfortunate justice and family, whose pantry stores were depleted thereby. The jury retired to the corn-crib to weigh the evidence and bring in a verdict, and the crowd waited in the yard. Old Ben had a peculiar habit of thinking out loud, and while moving about in the throng, oblivious to all, he soliloquized on the shortcomings of some of the witnesses who had testified against him, to the great amusement of the listening crowd. "There's old 'Batterhead'; he always was a liar, and they say that back where he came from nobody believed him on oath. Ant the T—s ain't much better; old 'Crane-neck' says that she can recollect when —— used to go without soles to his shoes, back in Indiana, and his own mother says that he used to be accused of stealin' sheep."

Old Ben is still alive, and is 91 years of age. He lives at Tingley, Iowa, but is nearing his end rapidly.

Pioneer Fogyism.

While the world is full of superstition, even at the present day, much of the old-time rot and rubbish growing out of an intermingling of ignorance and superstition has been swept away by the advance of education and a higher plane of intelligence. While superstition itself may not find as ready lodgement in the mind at the present day, there are yet thousands who do not or cannot eradicate their vagarisms and absurd fancies by philosophical inquiry or rational analysis.

Many farmers, even at the present day, will not plant potatoes or garden truck except during certain phases of the moon.

If he administers veterinary treatment to his pigs, calves, or other live stock, it must be when the "sign is right," or the animals will surely die. The "sign" which he consults is nothing more or less than the signs of the zodiac. For instance, if the sign is in the heart, the pig will surely die; at this fatal period the earth is passing through the constellation Leo. When the sign is in the neck, it is not quite so bad; this is when the earth is in the constellation Taurus. When the sign is in the feet, it is still better, since the sign is "going down," and the inflammation can with greater facility take its departure at the ends of the toes.

Another popular fallacy was that if a board were placed on the grass at a certain period of the moon's age, the grass would grow underneath it; but if placed there at another phase of the moon, the grass would not grow.

The housewife, when she saw a spider descending its web from the ceiling, knew that she would receive a visitor that day.

The young man or young lady who had warts rubbed them with an onion and then buried it beneath the window, and the warts were supposed to disappear.

The quack doctor and many of the old women of pioneer days incorporated these pernicious fancies in their medical practice. The midwife invariably recommended a rabbit-skin as a soothing application for the "weed." "Sheep-nannie tea" was good for measles.

A friend of the writer, residing in Blakesburg, and who is himself a physician, relates an episode and vouches for its truthfulness. Dr. Prather was a quack doctor and a "Hardshell" Baptist preacher combined; he assisted people in coming into the world, and also prepared them for their advent into the next. Brother Prather was called to the bedside of a Mrs. Jones, who was suffering intense pain; and, after making a thorough examination of the patient, he announced: "Yes, I see what the trouble is; I have been troubled in the same way myself." One of the old women present, who knew more about the patient's condition than the doctor did, disputed with him, explaining that it was impossible for a person of his sex to be similarly afflicted. The doctor and the woman finally agreed in a diagnosis of the case, and the physician stated that he must have the skin of a black cat to lay upon the patient's stomach. "It must be a very black one, and better send the boys out to hunt one while we pray." A crowd joined in the chase, and several black cats were brought in, including one polecat. The poor woman died during the night. Brother Prather said that if he had arrived a little sooner, he could have saved her; but when he preached her funeral sermon, he stated that "her time had come — the Lord had seen fit to take her to his own." The "Hardshell" Baptist believed more in the skin of a black cat than he did in foreordination and predestination, in the case of his patient, for he still insisted that he could have saved her if the cat-skin had been applied soon enough.

Our medical friend relates another story of Dr. Prather, and if the reader doubts his veracity, further substantiation of the tale may be added by the fact that there are to this day many living descendants of the yellow dog in the case. Bob Martin broke a leg, and Prather was sent for. Prather prescribed the skin of a yellow dog in which to bind the fractured limb. One was killed, and the skin promptly applied. The patient recovered, but the leg was crooked Prather explained that defect by saying that the dog had a few white spots on its belly, which had been overlooked.

The fumes from burning chicken feathers were considered a powerful remedy in alleviating the pains of childbirth.

The lack of intelligent and skilled medical practitioners in early days added most of the hardships of the early settler. However, they were mostly of robust constitutions and were seldom sick.

They Killed the Family Pig.

In about the year 1850, Wareham G. Clark and James Tracy started to Burlington with a load of wheat to have it ground into flour. While en route, a heavy snow fell and buried up the grass upon which the farmers were dependent for feed for their oxen. They were compelled to feed their oxen wheat along the road, and as they were five weeks making the trip, it took most of the wheat to feed the team. In their absence, their wives ran short of breadstuffs. The ladies were near neighbors, so they concluded to butcher a hog. They called it up out of the woods. One seized it by the hind legs, and the other knocked it in the head with an ax. They then scalded and dressed it, and on hog and hominy they lived until the return of their lords.

Transcriptions by Sharon R. Becker, September of 2010