| |

|

|

PIONEER HISTORY OF DAVIS COUNTY, IA -

1924

Dear Ladies of the Federation of Women's

clubs:-

Having heard through an

old friend that you are collecting data of the pioneers of Davis

County I am sending you herewith a contribution.

My father, David

Creighton, with my mother, my brother two and one-half years old, and

myself six months old, moved from Pittsburgh, PA., in the fall of

1843, and settled in Salt Creek Township, Davis County, two miles from

the Des Moines river. My earliest recollections are of living in a

hickory log cabin, having a chimney built of sticks and mud. My father

who was a carpenter, built the first log school house on the land of

my uncle, William Davison. He built a hewed log house 11/2 stories,

with stairs. Neighbors used ladders. He built a mill and dwellings for

A J DAVIS, who afterwards went to the mines and become a millionaire.

In 1850, during the gold excitement, father drove oxen attached to a

covered wagon, across the plains to California. He would not remain in

Calif., because he was unable to hear from the family at home. The

indians had captured and destroyed the pony express. So the following

year, 1851, he set sail from San Francisco and returned to New York by

the way of Cape Horn. During the voyage he was becalmed 2 weeks on the

coast of South America. After landing he visited his mother in

Pittsburg, enroute to Iowa. In 1853, we moved to Troy, Iowa, to obtain

better opportunities in education. There we children attended Troy

Academy.

My father traded his

farm to Dr MILLER for a half interest in the saw mill, which long ago

disappeared. Judge EARHART owned the other half. Father developed the

saw mill still further and added burrs for grinding flour. He also

burned two brick kilns and one lime kiln ["fired" - to

make bricks for the new house] out on the farm before going

to Troy. The Civil War ruined father's business so he returned to

California by way of Panama in 1862. The family followed in 63' by

covered wagon. The journey required four months on the road from Iowa

to California. In Calif., my father engaged in fruit growing.

He lived to be 88 years

old. My mother, whose health was not good in Iowa, improved in the

milder California climate and lived to be 80. The family of 7 children

are now all gone except one sister, 75, who is blind, and myself, 82,

hale and hearty and still in possesion of my faculties, so the

children say. Mrs Nellie

CREIGHTON-Farmer, Schnectady, N Y

Early Days as Told Me by My Mother

Recollections

of Eleanor Creighton Farmer at 86

(With notes by Josephine Farmer Albrecht)

My forebears came from the British Isles—my

grandfather, Samuel CREIGHTON, from Scotland, grandmother from Wales.

She had a very sweet singing voice. My maternal great-grandfather came

from Ireland.

My

mother’s father died when she was six months old and she lost her

mother when she was twelve. She was the youngest of four children:

William, Sarah, Alexander and Jane [Gray]. William was a farmer and was

in the Civil War. He drove a team, being too old for the ranks. Sarah

married William DAVISON and they came to Salt Creek Township, Iowa, in

1845. He had a soldier’s suit and a cocked hat with a long white plume

on it. My cousin used to open the old haircloth trunk and let me gaze at

it. Said it was used for “muster day” in Pennsylvania. [This uncle

built an outdoor oven in Iowa like the ones he knew in Pennsylvania.]

Their children were: Robert, Elizabeth, Mary Martha, Ann, Eliza Ann,

William A., and Amanda. “Billy” is the only one alive and lives in

Fairfield.

My

grandfather [mother’s father, Samuel GRAY] died young. He came from

Ohio to Pennsylvania. My parents were married in Sharpsburg, Dec. 28,

1838. I was born in Alleghany City Feb. 8, 1843 in a snowstorm. My

brother (Sam) was two years older than I.

David’s

brother Sam did not like school so he worked on the farm when they lived

nine miles out of Pittsburgh. John, the eldest son of Samuel Creighton

and brother to David, left Pennsylvania and went to Canada. He was

careless about writing and was lost track of. James, third son of

Samuel, went to Oregon and settled there. John, James and William had a

taste for liquor, but Alex, Sam, and David were teetotalers.

At

the time I was six months, my parents concluded to go west. My father,

being a carpenter and cabinet maker, filled all available space and tool

chest with groceries, he having gone to Davis County, Iowa, previously

and secured two eighties adjoining [at $1.25 an acre] and begun the

erection of a hickory log cabin four logs high. [A man working alone

could not raise big logs higher. The cabin had a peaked roof that made a

porch in front. JFA]

We

went down the Ohio in a flatboat. My mother said an old gentleman came

near sitting down on me, I was so small. While waiting to cross over to

Keokuk, Iowa, some “Latter Day Saints” were trying to carry off my

father’s precious tool chest.

We

drove the thirty miles in an ox wagon to find our house was as

[unfinished as] my father had left it. As it was warm, we slept outside.

Richard RAMSEY, being a kind but slow young neighbor, was quite sorry

[he probably had promised to work on the house during David’s absence-JFA],

and made haste to “hope” [help] father to make clapboard and cover

the cabin. They later built a lean-to with a mud-and-stick chimney to a

large fireplace, the door being in the end. [Nellie said they lived in a

lean-to at first, but that probably wasn’t the structure she means

here. JFA]

They have told me the

first New Year’s Day they sat outdoors, the weather was so mild, but

not so now. The floor to the lean-to was mother earth, packed down and

swept clean. There was two steps up into the main cabin where we slept,

and father’s workbench occupied one side where he made windows and

doors. He had match(ed) planes to tongue-and-groove and make sash. He

built most of the houses as well as the log schoolhouse in the little

town of Blackhawk, where the old Indian chief for whom it was named was

buried. Some rails marked his grave. The town (Blackhawk) was two miles

from our home on the Des Moines River. Father built A. J. Davis’s mill

that stored his High wines [high alcohol content or distilled like

brandy?] that afterward, taken out to the mines in Montana in which he

invested, made him a millionair(e), something he had always longed for.

But for the long hours

that constituted a day in those early times, Father could have walked

from home as he liked walking. As it was, he came home only on weekends.

Working by the river, he acquired malaria. [His diary records repeated

severe attacks in 1898. JFA]

One night, hearing a

commotion and people moving about in the room, I got out of bed to see

what the trouble was. My father caught me in his arms and put me back in

bed and in the morning I was shown a little baby sister named Isabell

JONES for my father’s mother. There was a girl in the kitchen getting

the breakfast. Her name was Melvina DODSON. My brother named Samuel (for

two grandfathers and an uncle) and I took a dislike to her for an act of

cruelty to our pet kitten. She had placed a pan of bread to rise under

the stove with a tablecloth over it. Kitty, seeking a warm place, was

found sleeping on top. No harm done, but she, in a bad temper, said she

would kill it. So when we could not find our pet we feared the worst. My

Mother asked us to go round the pasture fence and find where the geese

got out. There, hanging to the stake-and-rider fence was our little gray

kitten. We wept bitterly and told mother, who reproved her for such

cruelty.

Later in the fall when it

began to be chilly nights, my mother went to get the broom behind the

door. She found a snake coiled around the handle—a

house snake, and harmless. One cold night, fearing the little

young calf would freeze, my mother took a woolen quilt and covered it.

In the morning we found the corner chewed off.

My

father was much from home—having such long hours for a day, he could

only come Saturday evening. My father built a log schoolhouse on Uncle

Davison’s land. There were sliding windows on two sides, a door in the

front side, and a large fireplace occupied the remaining side. He made

all the desks and benches. As Sam was six, he was sent to school. The

way was long and lonely, being a cowpath through the woods two miles. He

would coax me to go for company altho’ I was but four. When I would

cry for mother, the teacher, Daniel MILLER, would take me on his knee

and promise to give me a “ticket” when I went home, and lay me on

the bench to sleep. One evening Father came and carried me home on his

shoulder. It had been raining long and hard, and the wet branches struck

me. I had on a new indigo-blue apron and my hands and dress were

streaked with blue, also my face where I had tried to protect it with my

sleeve. They had a good laugh at my expense.

My

Father got ague [malaria], working on the river [did not know about

mosquitoes]. He had it for two years, then took a trip to see his Mother

in Pittsburg(h) Pennsylvania, which cured him. He brought back presents

for us: bright dress material and picture books and news from the home

folks.

We

had a quarter section of good land all paid for, horses, cows, and two

houses: a hickory cabin four logs high and a hewed log house

one-and-a-half stories high with a stairway. My (Davison) cousins

climbed a ladder.

Now

it is not clear to me if there was likely to be trouble about our being

able to hold the other forty (acres). Father built on it a

story-and-a-half house of hued [hewed] logs with staircase. All the

other children had to climb a ladder. Father, having found lime and clay

suitable, had a limekiln burned, also two kilns of brick, and we had a

good brick chimney and shingled roof. The cabin [their first log house]

had a roof of clapboards that were split and shaved with a drawknife.

Our neighbor Adam ROWE built his family a brick house as they had a

large family (Dan, William, Polly, Sally, Burnettie, Delany, Felix,

Elisabeth, Catherine). They had lived in a double log cabin [See

Weslager: “The Log Cabin in America”—a double log cabin was two

separate cabins joined by one roof and a “dog trot.” JFA]

One

day after moving to our new house, my brother was allowed to ride Old

Sal. She was so gentle that I was allowed to ride behind him. All went

well until we got to the old cabin where weeds were grown up around the

porch [which was an extension of the roof]. Sam ducked, but I was

scraped off down into the weeds that were so large they scratched me.

[Evidently the old cabin was no longer in use after they moved to the

hewed log house on the other “forty.” JFA] I cried lustily but Sam

only laughed. He thought it was a good joke.

Our

family had been increased by a little curly-headed baby girl named

Sarah-Jane (Sade), called for my Mother Jane and her only sister (Sarah

Davison), whose family came out from Pennsylvania in 1845 [two years

after the Creightons] and lived two miles from us. We all got (w)hooping

cough, and Sade, being only three months old, Mother had to keep near

the cradle to keep her from choking. We older ones would lie down across

the chairs to keep from falling. Then we had to wear asafedita around

our necks to prevent getting other contagious diseases [See tiny

embroidered asafoetida bag with string in my collection. JFA]

One

day my father found us playing hide-and-seek in the tall wheat almost

ready to be cradled, and reproved us. [He was evidently a mild man! JFA]

My father was one of the best cradlers in Davis County, Iowa. The

sheaves of wheat were taken to a smooth piece of hard ground and beaten

with flails (two pieces of wood fastened together by a leather strap).

Later, horses were used to tread it out. This was in the late forties.

(Some difference from the present day combined harvester that puts it in

the sack! ECF) While harvesting was going on, my brother went over to

the field around the cabin to see the men work. As he jumped down from

the fence a rattlesnake struck him on the great toe. Mr. Rowe picked him

up in his arms, and being an old frontiersman, knew what to do: ran down

to the little stream that ran nearby, washed and squeezed it to make it

bleed, then took tobacco from his pocket and bound it on. My Father came

along on horseback from town, took him over home, and went for a doctor.

Meanwhile Mr. Rowe went to the little prairie, got button snakeroot and

steeped it to give him with whiskey to counteract one poison with

another. His leg swelled up to his body and turned spotted but his life

was saved by the prompt action. A little girl was bitten while picking

blackberries, ran all the way home, which accelerated her circulation.

She lost her life.

A

large limb from an oak tree in the yard was broken off by the wind. My

brother was chopping it into firewood. I went with my basket to get some

chips for Mother. He was swinging the axe around as he saw men do, and

as I stooped behind him he struck my forehead, and when I came to I was

surprised to know how I got in the house. My father said it was well it

was not he that was chopping or I would have been killed. I was

surprised at the cloth around my head and the smell of camphor and why I

was in bed. In a few days I was all right and able to go to school

again.

Our

new house was quite comfortable. I was seven, brother nine. The gold

discovery in California excited my father. California had long been an

interesting place to do better than Iowa. The winters were so cold in

Iowa while [although] the soil was rich.

The

preparation proceeded for my Father’s trip to California. Mr. Rowe and

his son William and my Father had one wagon, a yoke of oxen and a yoke

of cows. We had a large red cow we called Pink; their cow went dry. They

went through to California.

Father

“put in” a barrel of flower [flour, for extra provision—JFA]. Corn

was our bread, usually baked in a Dutch oven by the fireplace. My Uncle

Davison built an outside oven, such as they had in Pennsylvania, for his

family. He agreed on providing wood in return for one of our cows. We

had two cows. He took the big red one we called “Pink” and left the

spotted one for us. We had a log barn behind the house for old Sal [the

horse] and her colt, a dapple-gray we called Dandy. Mr. Rowe and his son

William took the coffee mill as there was none in cans at that time. The

green [coffee] beans we had to brown. [I believe she means that when the

father left for California, the Rowes took their coffee mill in return

for provisions for the trip or aid to the family remaining behind. Later

the Rowes went West in the same wagon train. There is a later reference

about having sold the stove which they had brought from Pennsylvania,

all in preparation for the planned move.

JFA]

There

were other men and wagons. Father and Mother took us in the farm wagon

with Old Sal and Dandy hitched to it. Mother kept her shawl around her

shoulders. I wondered why, as the April morning was warm. (It somewhat

concealed her condition as she soon was to become a mother again. ECF)

She wept bitterly, not knowing what might happen to him going through

the unsettled country where the Indians felt the white man was

encroaching on their hunting grounds, shoving them back across the

Mississippi River. Aunty Davison gave them a coffee mill as there was no

canned goods to be had at that early day. [Must have been their previous

mill, which the Creighton family’s mill later replaced.] So the wagons

drive out on the road and were soon lost to view. [David drove one ox

team. JFA] Brother was 9, I was 7, Bell 5, Sade 2½. We children only

knew the want of a mother as our Father worked on the river and came

home only on Saturday nights. Mother loaded her brood into the wagon and

went home. They had an agreement to quit the use of tobacco, but Mother

kept her pipe until he came home a year later.

In

California things were very expensive: onions $1.00 a pound. They were

in the Mariposa mines and they had to have vegetables to prevent scurvy

(this was in 1850. ECF). San Francisco was principally sand dunes with a

few shacks along the waterfront. As there was no law in the mines, they

were a law unto themselves. The thief found stealing while the miner was

away at work was made to run the gauntlet: each man struck him as he ran

between the lines, with the admonition never to return to their camp or

he was liable to be shot. [David owned a sword-cane for protection in

San Francisco which Herbert Farmer had, but lost in his many moves. JFA]

This

was a hard year for my mother. In July Martha Elisabeth (Matt) was born.

Help was poor but the neighbors were kind as they are in pioneer times

and help each other. All had large families that had to help in field

and garden to raise sufficient to carry them through the winter.

Mother had to get on a horse and go to the Joneses to get their men to

shear our sheep as they were losing their wool going through the brush.

The baby was entrusted to my care.

There came up a dreadful

storm; the wind was so strong we feared the house would blow over. We

had one loose plank in the floor, so we shut the door, raised the plank

[as close to getting under the house as possible], and all knelt along

by it, said our prayers, and waited till the storm abated and Mother

came home. We had quite a story to tell. Children like to be reporters

of the latest news.

When Mother came in the

cabin, Baby Matt had been afraid of her after she had been gone for so

long because she was dressed in a pretty pink-and-green “shally”

[challis] dress she had brought from Pittsburg(h); Matt cried and

thought her a stranger but was so hungry that soon she did not mind the

dress.

Naturally Mother also had

to relate her experience. The former rains had raised the creek, so she

had to tie her horse to a tree and walk across on a fallen tree, she was

so anxious about her children alone at home. Coming back, Will Jones

helped her across the log as the water was so near it, it made her

dizzy. There was her horse, but the saddle was gone! Will suspected Jack

RUTHERFORD. They were a drinking, thieving bad lot. He went to the

house. Jack denied knowing anything about it. Will being grown and Jack

only a boy, Will threatened him and Jack went to the stable and showed

Will where he had hidden it. So Will saddled her horse and helped her

on, promising to come and shear the sheep.

We

ran out of stock feed during severe winter weather while father was

gone, so my brother took me on Old Sal behind him and went to the field

by the old cabin. We pulled the corn out of the snow-covered shock and

filled the sack for the horses and cows. We did not have mittens. Later

we ran out of both flour and cornmeal. Brother on Old Sal started for

the water mill but found the recent rains had raised the creek so he

could not cross, so he came back home. My Mother parched some of the

corn, ground it in the coffee mill, and cooked it for our supper. She

made mush and milk and we thought we had something new. [This must have

been before the Rowes got the coffee mill. JFA]

Our

wood gave out but a neighbor came with his ox team and long whip. His

overcoat was ragged. He was a drunkard; had a long beard and a big

muffler around his throat. Our old dog Tope would not let him come in.

He called to Mother and she told him to drop the whip. Then he came in

with the wood. The Des Moines River was out of its banks with the spring

rains.

My

Mother’s two brothers, William and Alexander GRAY, came to see her in

1851 while my Father was in California. I was seven. My brother

Sam hitched up Old Sal and Dandy to the farm wagon and put in chairs for

Mother and her two city brothers, and they drove to Uncle Davison’s

for a visit. Aunt Sarah had a new baby, a boy, Willie, and five other

children. They were older, she having lost two in Pennsylvania before

coming out to Iowa.

This

is my remembrance of Uncle William: he said of himself “a poor man for

dogs and children.” Uncle Alexander was very different. Mother loved

him. He gave us little books. Mine I read until I could recite it. Had

it in my hand reading while I held baby Matt (Martha) on the other arm.

She struggled to get down. She crept to the teapot on the hearth, turned

it over, and scalded herself. She recovered, while a little neighbor

baby who ran into a brush fire died. Matt scalded herself very

bad(ly) on her arms and stomach. Mother took the scissors and cut off

her clothes. Then there was long weeks caring for her. Neighbors came

and kindly helped. Our baby got well, and she is the only sister I at 86

have alive. She is blind but takes great comfort in her religion; she is

a Methodist.

I had a gathering in my

head. They put everything they could think of on it but nothing seemed

to do any good, until it broke. Then for a time I was deaf. During this

time Davy T. Davis’ little boy ran into a bonfire the children had

made, and he died.

My

mother suffered with bad teeth, there being no dentist. [In those days,

the saying went that a woman lost a tooth for every child. JAN] To

deaden the pain she took laudanum [tincture of opium]. One night we

children were gone to bed and she, feeling so drowsy, feared she had

taken too much. She made a cup of strong coffee and drank it to

counteract the effect of the laudanum or we might have awakened to find

we had no mother.

Poor

health as she had, she was always there to tell us what and how to do

things. Her rheumatism got so bad she couldn’t dress herself, so she

gave Cousin Libbie her pretty “shally” [challis] dress for a brown

flannel that buttoned up the back. She told me how to make the cornbread

and bake it in the dutch oven at the fireplace, as they had sold the

small cookstove they brought from Pennsylvania. [No doubt it was too

heavy to take West. JFA]

One summer day my mother

said I might go to Mr. Rowe’s,

about three miles. I walked along quite spry until the road forked and I

could not decide which was the right road. In fear of getting lost, I

turned back with my mother’s message not delivered.

One

day the cows had wandered far and we three oldest were sent to hunt for

them. We took our dog Tope with us. We had crossed the creek and were

going down the other side, stopping to listen for the bell. Tope ran on

ahead and was barking at the end of a hollow log. Sam said he had treed

a rabbit, so he placed me at the small end with a stick to tap on the

log to scare it down to the open end where, if Tope failed to catch it,

he stood ready with a stick to strike it. [Rabbit stew would have been a

good meal. JFA]

Well,

Tope got it—a skunk! —and he was a sorry dog. He ran down to the

creek, rolled in the sand, vomited, washed his mouth, and tried to get

rid of the smell. We did not want him near us and that troubled him as

we were always kind to him. We had spent so much time that we were late

bringing the cows home. We were very tired, but Mother told me if I

would hold Mattie while she milked, I might sleep with her. This was a

great inducement so I stayed up. Mattie was fretting with her teeth.

Another

evening the horses had wandered far. Sister Bell and I went with Sam who

heard the bell and told us to stay on the path while he went into the

brush and got Old Sal and we would ride home. He came back with the bell

and said it was not on our horse. It was quite dark when we got home and

Mother was troubled lest the bell was not ours. While we were eating our

supper, Old Sal whinneyed at the gate. Sam was glad as she had no bell

on and it proved he was right. Of course it was Jack Rutherford, the one

bad boy of the neighborhood.

Snow

came, and we were barefooted at school, but we ran fast and did not mind

the cold.

[After

13 months in the California mines, not having received any of the

family’s letters due to Indian attacks on the Pony Express, David

returned to Iowa in 1852. Having been becalmed for two weeks in the

doldrums along the coast of South America, he landed in New York, going

west again to Iowa by stage and river boat. He remained in Iowa with the

family until the spring of 1862, when he started again for California,

going via Pittsburgh, where he saw his mother for the last time, thence

to New York, and across the Isthmus of Panama (the Isthmus railway

opened in 1855), and on to San Francisco, then inland to Vacaville,

where he worked at his trade by day and planted an orchard by moonlight.

He left his carpenter tools in Iowa because of the weight, so he must

have bought new ones in California. JFA]

In

the fall of 1853 we moved to Troy, Iowa, where my father bought a

sawmill, to which he added a grist mill and one for carding wool. The

object of this move was to provide better schooling for the children at

the Troy Academy.

Herbert

P. Creighton, the youngest son of Samuel, Jr., was in the

Spanish-American War. His ship was run on the rocks in the Philippines,

where Bert lost all his belongings, including his savings.

After

David had moved to California, about 1880 Samuel, who had been living in

Ohio and was just recovering from a serious illness, was sent by his

folks to California. He stopped at Eleanor Creighton (Nellie) Farmer’s

house in Elmira near Vallejo, and she drove him to his brother David’s

fruit farm just outside of Vacaville. At Samuel’s request, Eleanor

stopped at a neighbor’s house (the Allisons) while Samuel went ahead

on foot to see if his brother, whom he had not seen in 37 years, would

recognize him. He was to play the part of a book agent, for Nellie knew

that a book agent was persona non grata with her father, but she did not reveal this to

her uncle.

A

most remarkable occurrence took place. As Samuel walked down the long

lane, which was flanked by a wealth of flowers, he was seen approaching

by his sister-in-law, Jane Gray Creighton, and she remarked to her

husband: “If Sam Creighton were in this part of the country, I should

say that was he by his walk.” Her suggestion “spilled the beans”

to David, and Samuel’s joke was spoiled. Samuel did not limp or have

any peculiarity of gait that anyone else noticed, but Jane Creighton had

a peculiar memory for strides.

|

|

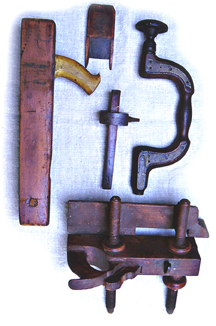

David Creighton's Tools

. Nellie

Creighton

|