Ray, Isaac

Co G, age 18, born in Iowa, residence Millville

08/15/62 enlisted

08/22/62 muster in Co. G

09/09/62 muster in Regiment

08/01/64 promoted to 8th Corporal

07/15/65 muster out Baton Rouge

This is from the R&R. I have not verified the

information

~*~*~

Reed,

William T.

Records are in conflict as to where William was

born. The Company Muster-in Roll says he was born

in Illinois, but his Descriptive Book says he was

born in Jackson County, Iowa. A book about La

Crosse, Wisconsin, says Iowa. Records also

conflict regarding the year of his birth which

was in:

-1831 or 1832 according to a medical report and

three affidavits signed by William,

-1832 or 1833 according to a medical report and

one affidavit signed by William,

-1833 or 1834 according to a medical report and

the Muster-in Roll, and

-1836 (approximately) according to the book about

La Crosse, Wisconsin.

William was working as a McGregor barber when, on

August 15, 1862, he enlisted as a Private in

Company G then being raised by the town's

thirty-two year old postmaster Willard Benton.

The company was mustered in on August 22, 1862,

with Benton as Captain. William's Descriptive

Book described him as being 5' 9¾'' tall,

"Eyes Dark; hair dark; Complexion

Dark." He was possibly the only man

apparently of mixed race who served in the

regiment; his wife, Amanda, was white. Bruce L.

Mouser, Professor Emeritus, University of

Wisconsin-La Crosse, Black La Crosse, Wisconsin,

1850-1906: Settlers, Entrepreneurs, &

Exodusers (La Crosse Historical Society, June

2002), page 33. Mr. Mouser can give no assurance

regarding William's race, but says "the only

conclusion one can make about the 'M’ in the

census and marriage record is the fact that the

census enumerator and the register of marriages

thought he was a mulatto."

Of the eighty-seven men on the rolls of Company G

when its ten companies were mustered in as the

state’s 21st regiment of volunteer infantry

on September 9, 1862, William was one of only

forty who served their entire terms and were

mustered out at Baton Rouge and one of the few

who were marked ''present" on every

bimonthly Company Muster Roll from the time of

their enlistments to their discharge almost three

years later.

Records conflict slightly regarding his rank. All

bimonthly Company Muster Rolls give his rank as

Private during his entire service, but

William’s Descriptive Book and the

Muster-out Roll say he was promoted to Corporal

on February 24, 1863 and reduced to the ranks on

March 19, 1863. On February 27th, one of his

comrades wrote a letter indicating that “G.

White, P. McEntire, Wm T Reed are

Corporals.” While that seems to confirm the

short-lived promotion, the February 28th Company

Muster Roll for the same time frame says William

was still a Private.

William's early service in Missouri went well and

he was with the regiment when it crossed the

Mississippi River to Bruinsburg, Mississippi, on

April 30, 1863, and started inland on the

Plantation Road with Companies A and B as

skirmishers. The skirmishers were pulled in after

dark while Lt. Col. Dunlap, four others and their

guide, a former slave, took the lead under

ominous orders to ''proceed without halting on

the main road to Port Gibson until they met the

enemy and were fired upon." About midnight,

enemy pickets fired. Ineffective shots were

exchanged in total darkness for almost two hours

until men rested and slept on their arms. The

day-long Battle of Port Gibson (also known as

Magnolia Hills and Magnolia Church) followed

after daylight on May 1st with William Reed

participating.

He was also present when the regiment was held in

reserve on May 16th during the battle on

Champion's Hill and he participated in the next

day's assault at the Big Black River when the

regiment suffered 7 killed in action, 18 fatally

wounded, and at least 38 wounded non-fatally. One

of the most seriously wounded was the

regiment’s colonel, McGregor resident Sam

Merrill, who fell on the field while leading the

charge. William also participated in the May 22nd

assault at Vicksburg when the regiment suffered

23 killed in action, 12 fatally wounded, and at

least 48 wounded non-fatally. He was with the

regiment during the siege of Vicksburg and in

November 1863 when it left New Orleans for Texas,

but there he had a problem.

On May 29, 1864, Frederick Richardson, Orderly

Sergeant from Millville, detailed William for

guard duty on Matagorda Island, but William

refused. He said he was sick but, when "sick

call'' was made, William did not appear. Sgt.

Richardson couldn’t find him, but walked

down to the landing and, on the way, met William

who "had apparently been down there"

without permission. The next morning, Sergeant

Richardson "detailed him for guard again and

asked him why he went to the landing" the

previous day. "I then told him he must

either report to the doctor or go on guard"

As near as Sergeant Richardson could remember,

William replied that Richardson could "suck

his arse."

At a court martial hearing later that day,

Richardson recounted the events, Private Obed

Harrison (Millville) testified that William had

said "he would just go wherever he had a

mind to," and Captain John Craig (Millville)

confirmed that he had not given William

permission, and William had not asked permission,

to go to the landing. William presented no

defense, was found guilty of "conduct

prejudicial to good order" and was sentenced

"to be confined in some government fort to

be designated by proper authority for the period

of thirty days with a ball & chain attached

to his left leg." The next day, Fort

Esperanza was designated as his place of

confinement.

William was released on June 26, 1864 and

completed his service without incident. He was

present during the regiment's participation in

the successful campaign against Mobile the

following April, its garrison duty processing

arms and prisoners in Arkansas, and its

mustering-out at Baton Rouge on July 15, 1865.

Postwar, he initially returned to McGregor but,

in the fall of 1866, moved to Lansing, Iowa for

"a short time," and then to La Crosse,

Wisconsin where he continued his prewar

occupation of barber for several years. From 1871

until October 1889 he moved about (“not

lived much in one place,” he said) and lived

in Eau Claire, Chippawa Falls, Menomonee and

River Falls. He then returned to La Crosse where

he joined the Wilson Cowell Post of the G.A.R.

By 1890 his health had declined to a degree that

made it difficult to continue earning a living by

manual labor. He applied for a pension and said

he had rheumatism, kidney problems and failing

eyesight. Friends and doctors confirmed his

condition and a $6.00 monthly pension was granted

in 1891 for “impaired vision,” an

amount raised to $8.00 in 1902. In April 1904 he

was living in Superior, Wisconsin, and said he

was "completely broken down" and

"totally disabled from any labor." He

was receiving an age-based $12.00 monthly pension

when he died in 1905. William is buried in

Superior's Greenwood Cemetery where he has a

standard issue military stone.

Except for a single reference regarding a

marriage to "Amanda,'' no information has

been found regarding his wife, parents, or any

siblings or children.

~*~*~

Reeves, Charles Henry

Charles Henry Reeves said he was born in

Bloomington, McLean County, Illinois, on April

22, 1842. Ann Elizabeth “Annie” Watson

was reportedly born in Prairie du Chien,

Wisconsin, on August 4, 1846. On July 4, 1861,

they were married in Prairie du Chien.

During the Civil War, Charles was enrolled on

August 11, 1862, at McGegor, Iowa, in a company

being raised by William Crooke. Charles’ age

was given as twenty-two (which doesn't correlate

with the date he said he was born), his

occupation as painter, and his description as

being 5' 8" tall with blue eyes, brown hair

and light complexion.

They were mustered in as Company B on August 18th

and as the 21st Regiment of Iowa's volunteer

infantry on September 9th. After brief training,

they left Dubuque on a rainy September 16, 1863,

on board the Henry Clay, spent one night

in St. Louis, and then traveled by rail to Rolla.

For the next several months their service was in

Missouri - Salem, Houston, Hartville, back to

Houston, and then south to West Plains. From

there they moved to the northeast - Eminence,

Ironton, Iron Mountain and Ste. Genevieve.

On April 1, 1863, they left Ste. Genevieve on the

Ocean Wave and several days later

reached Milliken's Bend, Louisiana, where General

Grant was organizing a massive army at the start

of what would be a successful Vicksburg Campaign.

They crossed to Bruinsburg, Mississippi, on April

30, 1863, and began a march inland.

Charles participated in the day-long battle of

Port Gibson on May 1st, was present during the

battle of Champion's Hill on May 16th when the

regiment was held in reserve by General

McClernand, participated in an assault at the Big

Black River on May 17th, and participated in an

assault at Vicksburg on May 22nd during which

Charles suffered a slight head wound. The ensuing

siege lasted until July 4, 1863, when the city

was surrendered. The next day, he was with the

regiment and other federal troops as they started

a pursuit of Confederate General Joe Johnston

east to Jackson.

Charles apparently had culinary skills, at least

those sufficient for the military. In July 1863,

after their return from Jackson, he was detailed

as a cook in a Vicksburg hospital, in August he

was a cook on the hospital boat Nashville, and

from September 28th to November 3rd, 1863, he was

a kitchen steward in a Vicksburg hospital. After

being relieved, he reached his regiment a week

later at Brashear City in Louisiana. He remained

with the regiment during its subsequent service

in Texas and, after returning to Louisiana, was

again detailed as a hospital cook, this time on

August 27, 1864 at Morganza.

During the regiment's 1865 campaign to occupy the

city of Mobile, Alabama, Charles became ill and,

on March 17th, was admitted to a hospital on

Dauphin Island where the remains of Fort Gaines

are still standing at the entrance to Mobile Bay.

Regimental muster rolls continued to report him

absent and sick on Dauphin Island for the

bimonthly periods ending April 30 and June 30,

1863, He was then transferred to a camp of

distribution (a camp for soldiers awaiting

reassignment) in New Orleans where he was treated

for intermittent fever.

In the meantime, his regiment had completed its

service and was camped in Baton Rouge while

muster-out rolls were prepared for 1,126 men

(those on the original rolls and those who

enlisted subsequently as new recruits). The war

was over and soldiers were anxious to go home. On

July 15, 1865, the regiment was mustered out and,

on the morning of the 16th, the men in Baton

Rouge started north on board the Lady Gay

- but Charles was still in New Orleans waiting

for orders.

On July 20th, the same day his regiment debarked

at Cairo, Illinois, Charles reached Baton Rouge.

With his regiment gone, he reported to the

Provost Marshal's office where the captain in

charge saw "no reason why the man should not

be furnished transportation to Davenport Iowa

where his Reg't was sent." Before the day

was out, an assistant adjutant general was able

to report "transportation furnished to Cairo

Ills." and Charles was on his way. His

Descriptive List and other papers had gone north

with the regiment but, by July 31st, he reached

Davenport where orders were received that

"this soldier will report without delay . .

. at Clinton for muster out of service. The AQM

will furnish transp. no papers."

Charles said he and Annie lived in McGregor for

about twenty years until they moved to

Cumberland, Wisconsin. That’s where they

were living when, in 1885, Charles applied for a

federal pension based on various ailments he said

were contracted during his service in Mississippi

and Texas. The Adjutant General’s office

verified some of the ailments and the slight head

wound, but the claim was still pending when

Charles moved to Idaho.

In February 1896, while living in Wallace, Idaho,

Charles reapplied for a pension, referenced some

of the same ailments mentioned earlier, and also

claimed to have received a wound from a shell

during the assault at the Big Black River. Again

his claims were investigated. In addition to the

ailments reported earlier, the Record and Pension

Office said he was treated for intermittent fever

(malaria) for six days in July 1865 while waiting

to be discharged. It found no record of a shell

wound, or any wound, received at the Big Black.

In June 1897, he was ordered to appear for a

routine examination before a board of pension

surgeons in Rathdrum, Idaho. In January 1898, Dr.

Frank Wenz advised the Pension Office that

Charles had failed to appear. That was about the

time he left Idaho and move eighty miles west to

Spokane, Washington. Another medical exam was

arranged for July 1898 in Spokane and this time

Charles appeared. He complained of the same

ailments referred to earlier, mentioned malarial

poisoning that the Record and Pension Office had

noted, and said he now also had “stiffness

of right hip,” but he made no reference to

any wounds. Witnesses said he was credible and

had good morals but, based on the surgeons’

certificate, a Medical Referee said Charles was

not ratably disabled.

In 1907, a new law authorized pensions based

solely on age provided the soldier had served at

least ninety days and received an honorable

discharge. Charles applied, but encountered a

difficulty when the Pension Office realized that,

while he consistently signed his name as

“Reeve” (eventually on eleven different

documents), he was listed as both

“Reeve” and “Reeves” in

military records. After inquiry, they agreed his

correct surname was “Reeve” and he was

granted a $12.00 monthly pension, payable

quarterly. New laws allowed for increases at

various ages (66, 70, 75), but Charles had

difficulty proving his age. The age given at

enlistment didn’t correlate with the claimed

birth date and, he said, the family Bible in

which records were kept had been lost in an 1857

fire. It took several more years and affidavits

from Annie and one of their daughters (both of

whom signed as “Reeve”) but,

eventually, Charles received increases to $24.00,

$30.00 and $72.00.

During his career in the west, Charles had worked

as a barber in Wallace, Idaho, joined the Reno

Post of the G.A.R., was active in various lodges,

enjoyed Honey Dip twist tobacco, become

interested in lead and silver mining activities

in the Coeur d'Alene area, and was one of the

early promoters and a part-owner of the Hercules

Mine in Burke, Idaho. As an obituary reported:

''The faith of Mr. Reeves

is believed to have been an important

influence in the mines' development, for when

one partner or another would despair of

success, his optimism in his barber shop at

Wallace, would encourage continued

work."

Although he sold most of his

holdings in the mine, he "retained enough to

secure a comparatively large fortune" and at

one time owned extensive property in Spokane.

In 1927 Charles and Annie celebrated their

sixty-fifth wedding anniversary. Later that year,

on December 27th, Annie, the "mother of 15

children," passed away at the family home,

1917 East Fifth Avenue, Spokane. She was buried

in the city's Riverside Park Cemetery (now

Riverside Memorial Park).

A certificate increasing Charles’ pension to

$90.00 was issued on May 7, 1928, but, on May

20th, Charles died, only five months after the

death of his wife. Several "old

soldiers" were present when he was buried

next to Annie in Riverside Memorial Park.

Despite the “Reeve” spelling they gave

in pension documents and when they signed their

names under oath before notaries, their surname

is given as “Reeves” in their

obituaries, on their gravestones, and elsewhere.

As indicated in Annie’s obituary and by

Charles in pension documents, they had fifteen

children. Six died before Charles, but he was

reportedly survived by five daughters, four sons

and sixteen grandchildren. The birth dates, and

even the given names, were sometimes inconsistent

but their fifteen children were Ella, Carrie, Ida

Mae, Jessie, Lemuel, Josephine, Mildred, Jay A.,

Roger, Frank, Reo, Arthur Earl, Sidroe (aka S.

D., Sydney and Sadie D.), Harry Harold, and

Elizabeth June “Bess” (aka B. E. and

Bessie).

~*~*~

Reynolds, Nelson R.

In the decade before the Civil War, immigration

to Iowa, especially from New York, Ohio,

Pennsylvania and the New England states was

extremely heavy, so heavy, said one article, that

in 1856 only 17% of Clayton County’s

residents had been born in Iowa. Nelson Reynolds

was one who emigrated from New York. The son of

Lester and Anna Reynolds, Nelson was born in the

town of Stuyvesant on March 25, 1842. By the time

the war started, he was living near McGregor and

working as a farmer.

Emigrating from Connecticut in 1855 was Rev.

Isaac Stoddard, his wife (Delia or Celia), son

(Benjamin) and daughter (Mary). The Stoddard

family settled in Clayton County and lived in

McGregor where another son (Isaac C.) was born.

In 1859 they moved to Grand Meadow Township.

On August 14, 1862, Nelson was enrolled by

McGregor postmaster Willard Benton in what would

be Company G of the 21st Iowa volunteer infantry.

The company’s Muster-In Roll said Nelson

enlisted at Millville, but he later said his

enlistment was at McGregor. He was described as

being 5' 9½” tall with grey eyes, brown

hair and a light complexion. Company G was

mustered into service on August 22nd at

Dubuque’s Camp Franklin. On September 9th,

ten companies were mustered in as a regiment.

Training was essential for men, mostly farmers,

who were unfamiliar with military discipline and

the ways of war, but the training was brief and

hampered by an outbreak of measles that spread

quickly in the close confines of the barracks. On

a rainy September 16th, those able to travel

marched through town and boarded the sidewheel

steamer Henry Clay and two barges tied

alongside. They arrived at Rock Island on the

17th and Montrose on the 18th. Due to low water,

they spent the 19th traveling by rail to Keokuk

where they boarded the Hawkeye State and

resumed their trip to St. Louis where they spent

the night of the 20th before boarding rail cars

on the 21st and heading west to Rolla.

They then camped southwest of Rolla for almost

four weeks. While there, Grand Meadow resident,

Jim Bethard, wrote home and told his wife that

“Wm Barber and Nelson Runels have had the

measles but are on the mend.” Three of their

comrades died from measles and at least another

three deaths were attributed to lung problems

following measles.

Company rolls were taken bimonthly and Nelson was

marked “present” on rolls taken October

31st at Salem, December 31st at Houston and

February 28th at Iron Mountain where Nelson was

detailed as a teamster. On March 11th, they

reached Ste. Genevieve on the Mississippi River

and camped on a ridge north of town until April

1st when they boarded several transports and went

downriver to Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana,

where General Grant was organizing a large army

to capture the Confederate stronghold of

Vicksburg.

On the 12th, Nelson was ill and left behind when

the regiment started south, walking along roads

and crossing bayous west of the river. On April

30th, they crossed from Disharoon’s

Plantation to the Bruinsburg Landing on the east

bank and, the next day, fought the daylong Battle

of Port Gibson. Nelson was not present, but

caught up on the 15th. On May 16th, the regiment

was held in reserve during the Battle of

Champion’s Hill. William Crooke, then

Captain of Company B, expressed the feelings of

many when he said, “those who stood there

that day will surely never forget the bands of

humiliation and shame which bound them to the

spot, while listening to the awful crashes of

musketry and thunders of cannon close by."

Two companies, A and B, engaged in light

skirmishing after the battle but, if allowed to

move two hours earlier, Crooke thought

Confederates under John Pemberton "would

have been compelled to surrender right there -

bag and baggage.”

Having not participated on the 16th, they were

rotated to the front on the 17th and, with the

23d Iowa, led an assault on entrenched

Confederates at the Big Black River. The assault

took only three minutes, but seven in the

regiment were killed, eighteen others had wounds

that would prove fatal and at least forty had

non-fatal wounds, some serious and others not.

They were allowed to rest and care for the dead

and wounded while the Confederates withdrew to

their base in Vicksburg and the Union army

followed.

Hoping to profit from what he thought was a

demoralized enemy, Grant ordered an assault for

the 19th that failed. With more troops and better

information, he ordered another assault for the

22nd. This time, the 21st Iowa was present and

joined in the attack, but this assault also

failed and the regiment suffered its heaviest

casualties of the war: 23 killed, 12 fatally

wounded and at least 40 with non-fatal wounds

some of which led to amputations of arms and

legs.

Many of the wounded lay on the field between the

lines. One was William Barber. It was two days

before a brief truce was called and Nelson helped

carry his friend to the surgeon’s tent. In a

postwar affidavit, Nelson described how “Dr

Orr administered cloform to him, while a surgeon

I did not know, dressed the wound by injecting a

preparation into the wound that caused large

quantity of maggots to come from the wound. The

surgeon probed for the bullet but could not

locate it. I remember that the surgeon said the

bullet was still in the hip but that he could not

at that time locate it. I was with the said

William C. Barber a part of each day for several

days after he was taken to the hospital and

helped to care for him and saw his wound dressed

a number of times.”

On June 20th, federal artillery pounded Vicksburg

and Isaac Stoddard’s wife died in Jesup,

Buchanan County. She is buried in the city’s

Cedar Crest Cemetery. The Vicksburg siege ended

on July 4th and, on the 13th, Jim Bethard wrote

home and told his wife he had received her recent

letter and “was sorry to hear the news of

Mrs Stoddards death I deeply sympathise with Mr

Stoddard for he has been bereft of a great

treasure.”

The regiment went into camp at Carrollton,

Louisiana, on August 15th and, two weeks later,

Nelson Reynolds was granted a sixty-day sick

furlough and headed north. Late returning, he was

briefly regarded as a deserter but rejoined the

regiment at Indianola, Texas, in late January and

was returned to duty without loss of pay. During

the next several months he spent part of the time

as a company cook and part as a guard at brigade

headquarters. On August 1, 1864, he was promoted

to 6th Corporal but, in October, became sick and

was admitted to the Washington U.S. Army General

Hospital in Memphis. While there, without

explanation, he was reportedly reduced to the

ranks. On June 2, 1865, with the war nearing an

end and still in the hospital, Nelson was

individually mustered out of the service.

In 1867 Rev. Stoddard bought 160 acres near

Jesup. Still living at home was his daughter,

Mary May Stoddard, who was born in Connecticut

(New Haven or Gales Ferry) on October 28, 1849.

On November 18, 1868, a month after her

nineteenth birthday, Mary and

twenty-five-year-old Nelson Reynolds were

married. They moved to Winthrop in 1869 and then

to Jesup and Parkersburg before settling in

Luverne, Minnesota in 1873. They had three

children - Clifford born in 1869, Hattie in 1871

and Clayton in 1877.

In 1891, Nelson applied for a pension indicating

that, at forty-nine-years of age, he was unable

to perform manual labor due to “Disease of

the Kidneys” that he attributed to a cold he

contracted twenty-nine years earlier in Rolla

while convalescing from measles. After two

medical examinations, the Bureau of Pensions

concluded he was not disabled “to a ratable

degree.” Nelson applied twice more and a

$6.00 monthly pension was finally granted in

1904. He applied several more times and received

gradual increases, ultimately being approved in

1917 for $30.00.

From Luverne, Nelson and Mary moved to California

where their son, Clayton, was living. Clayton

died in 1927. Five years later, giving their

residence as Arcadia, Mary wrote to the Director

of Pensions. Nelson was “under care”

and she asked for forms so she could request

another increase on his behalf. “Surely the

World is all O.K. and beautiful is it not? But

age comes finding myself 83 years. But desirous

of continued effort. When chance comes sickness

must be met. I married said veteran in 1868 - 64

years came. Was 18 [sic]. Long, long road, was it

not? Children in heaven, save one in

Honolulu.”

In 1934, Nelson was admitted on an emergency

basis to a Veterans Administration facility in

Los Angeles where he was eligible for hospital

and domiciliary care. A friend told the VA that

Mary had cared for Nelson for the last four or

five years “when he really, should have been

in the care of the Hospital and she is all worn

out” while Mary said she had gone

“nearly entirely without sleep or rest”

while caring for her husband. Nelson died on

September 20th of that year and was buried near

Clayton in San Gabriel Cemetery.

Mary, still living in Arcadia, wrote to the

Veterans Administration and applied for a

widow’s pension - “God bless our

America, loved loyal lands,” she said. Mary

was awarded $38.00 monthly. In 1941 she requested

an increase. She had recently had cataract

surgery on one eye, the first time in eight years

she “had even a speck of light” but,

with the help of a “glass” was able to

write her own letter. The increase was denied

since she had not been married to Nelson while he

was in the army. Mary died on June 2, 1944, and

was buried next to Nelson in San Gabriel

Cemetery.

~*~*~

Rice,

James Marshall

Emigration from Ohio to Iowa was very heavy in

the pre-war years. In 1853, Fortner Mather moved

from Union County, Ohio, to Clayton County to

become pastor of a Methodist Episcopal Church.

Four of his brothers - Darius, Sterling, Esquire

and John - followed as did their aunt and uncle,

Joel and Sarah Rice, with their six children -

George, James, Carolyn, Robert, Tero and

Marshall. Following the Rice family, or at least

Carolyn, was Jim Bethard. Carolyn and Jim were

married in 1858 and, on October 1, 1861, her

brother, Jim Rice, married Elizabeth

“Lib” Stevenson.

In the fall of 1862, with casualties from wounds

and illness mounting, President Lincoln called

for 300,000 volunteers. On August 11th, Jim Rice,

his cousin John Mather and his brother-in-law Jim

Bethard enlisted in the infantry at the Grand

Meadow depot (between Luana and Postville). With

three others, they called themselves “the

Roberts Creek crowd.” They were mustered in

as part of ninety-nine man Company B on August

18th and, on September 9th, ten companies were

mustered in as the 21st regiment of Iowa’s

volunteer infantry.

On a rainy September 16th, members of the

regiment walked from Dubuque’s Camp Franklin

to the levy at the foot of Jones Street where

they crowded on board the four-year-old steamer Henry

Clay and two barges tied alongside and

started south. After transferring to the Hawkeye

State, they reached St. Louis on September

20th and Rolla, by rail, on the 22nd. Jim Bethard

wrote weekly letters to Caroline

(“Cal”), always sharing news of her

brother and cousin so Cal could share the news

with Lib and other family members. From

Hartville, Missouri, on November 15th, he said

her brother “Jim and John and I have

discovered that it [tobacco] is a nautious weed

and therefore we abstain from the use of

it.” On December 13th they were in Houston

during a heavy rain when Jim wrote that

“there is no less than four writing in the

tent and Jim Rice is laying with his feet against

my back trying to sleep and every once in a while

he gives me a punch in the back with his

feet.”

From Houston they moved to Hartville, then back

to Houston, south to West Plains and northeast to

Ironton, Iron Mountain and Ste. Genevieve before

being transported downstream to Milliken’s

Bend where General Grant was organizing an army

to capture Vicksburg. Still west of the

Mississippi, they walked south on roads, across

plantations and through swamps and bayous. Along

the way, Jim Bethard became sick and was left

behind, but Jim Rice, John Mather and others able

for duty continued south and, on April 30, 1863,

crossed the river to Bruinsburg.

On May 1st they fought in the Battle of Port

Gibson and on the 17th participated in an assault

at the Big Black River. On May 22nd, Jim Rice,

but not John Mather, participated in an assault

at Vicksburg. Jim Bethard caught up with the

regiment on June 4th and told Cal her brother was

well. On the 15th, he wrote that “James Rice

has had rather a bad streak of luck having lost

his pocket book containing all his money which

was about $17.” On June 19th, John Mather

died from the debilitating effects of chronic

diarrhea.

The siege at Vicksburg ended with its surrender

on July 4, 1863. The regiment had suffered 31

killed in action, 34 who sustained fatal wounds

and at least 102 who received non-fatal wounds

during the campaign, but “the two Jims”

were well and participated in the regiment’s

next campaign, an expedition to and siege of the

capital at Jackson. They arrived back in

Vicksburg on July 23rd and, on the 26th, Jim Rice

was granted a thirty day furlough to go north. On

August 23rd, with the furlough nearing an end,

Jim Bethard wrote to Cal that “I suppose Jim

is beginning to think about packing his duds to

start back,” but that was not the case since

her brother had become ill. “I am sorry to

hear of Jims illness,” Jim Bethard wrote on

September 13th. “I think it is curious that

he has that diahrea so much at home after having

his health so well in the army it was lucky for

him that colonel Merrill was at McGregor to give

him leave to stay ten days longer.” The

furlough stretched beyond the ten days and it was

November 4th before Jim Rice reached the regiment

then at Camp Pratt in southwestern Louisiana. Jim

wrote to let Cal know her brother “was as

tickled as a stray dog that has just found his

master when he came to the company and the boys

were all equally as glad to see him.”

In late November they were transported across the

Gulf for service on the coast of Texas where

James Rice was promoted to 5th Corporal. He had

some minor health issues (“neuralga in the

head”) and was worried about “large

bills for house rent and meat,” a concern

made worse when others received two months’

pay but he didn’t. The money was due, but

there was an apparent problem with muster rolls

during his prolonged furlough months earlier. In

April, Jim told Cal that he and her brother were

healthy and “out on the beach last week as

far as we could get.” After returning to

Louisiana in June, 1864, they saw more service

west of the river and along the White River in

Arkansas where “Jim Rice traded some sugar

for two chickens.” Jim Bethard cooked the

chickens “and made some soup and dumplings

and we had a splendid dinner . . . Jim said it

tasted old fashioned.” They were both

“hearty as bucks” and “in high

spirits over the prospects of the election of Old

Abe.” The regiment’s final campaign was

in Alabama where they occupied the city of Mobile

and “took a stroll around the city.”

They were mustered out at Baton Rouge on July 15,

1865.

After being discharged at Clinton on the 24th,

Jim Bethard left for Sigourney where Cal had

moved with her parents, but Jim and Lib Rice had

other plans. In October they sold eighty acres

they owned in Clayton County and in the spring of

1867 moved to Wright County as two of its early

homesteaders. Unfortunately, “through some

oversight in the numbers of his land at the land

office, he settled on the wrong piece and had,

after building and making his improvements, to

remove the buildings to the proper location in

the section, all of which caused him considerable

loss of time and money. But with a true, stout

heart he went to work and commenced all over,

finally gaining for himself and family a

desirable home” in Vernon Township.

Three children were born after the move to Wright

County: Sarah Evelyn “Eva” Rice on June

23, 1867, Helen Isobel “Nellie” Rice on

July 8, 1871, and Lenora “Nora” Mae

Rice on November 10, 1875. On February 28, 1877,

from Dry Lake in Section 16, Lib wrote to

Jim’s parents in Sigourney. Jim “has

gone to the timber for a load of wood,” she

said, and the “ground is in good rig to put

in wheat & oats.” Eva (9) and Nellie (5)

were anxious for their grandparents to visit, but

“dont see why grandma wants to call Nora a

little stranger for that she aint a

stranger.” Jim, “dont calculate to do

any braking this summer he is going to put in a

lot of corn and stay at home and tend it.”

An Odd Fellows lodge was formed in Dows and Jim

was one of the members, but the following month,

on June 8, 1882, Lib died. She was buried a few

miles to the south in Blairsburg Cemetery. Eight

months later Nellie would be buried in the same

cemetery.

In February, 1883, forty-five-year old Jim

married Mary Ann Valley on the 15th and prepared

for spring work on their farm and apple orchard.

In September, the Monitor reported that

he “handed us samples of Duchess apples

grown in his orchard this season, and finer

looking or tasting fruit it would be difficult to

find in any locality. Mr. Rice tells us that he

will have thirty bushels of apples, about

one-fourth of the crop he would have had only for

the late frosts in the spring.”

Children born to Jim and Mary Ann were Pearl Rice

born November 11, 1883, Maud Rice born April 8,

1886, and Harry Rice born February 11, 1889. Jim

continued his Odd Fellows membership, joined the

Grand Army of the Republic and was still working

his farm when a fire destroyed the commercial

district of Dows in 1894. Like most veterans who

fought for the North, Jim applied for an invalid

pension, a pension granted at $12.00 per month.

Mary Ann died in 1915 and was buried in

Dows’ Fairview Cemetery. Jim applied for and

received periodic increases to his pension and

was receiving $40.00 when he died “on or

about” August 7, 1919. Jim was buried in

Fairview Cemetery.

~*~*~

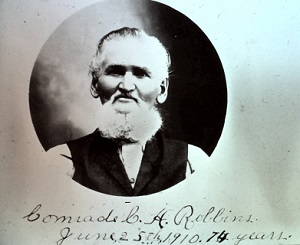

Robbins, Charles Henry -

'Charlie' or 'Fifer'

Comrade C.H. Robbins. June 25th, 1910. 74 years.

~photo contributed by Rita Knight Hill

The son of Henry and Relief

French Robbins, Charles Henry Robbins, was born

in what is now Ontario, Canada, on June 25, 1836,

the third of their children who were born in

Ontario. Six more children were born after they

moved to the United States.

On August 11, 1862, Charles ("Charlie"

to his friends; "Fifer" to his brother

William) enlisted in Company B of the 21st Iowa

Infantry, a regiment then being recruited in

Iowa's northeastern counties, its 3rd

Congressional District. He was described as being

a 5' 6¼'' tall painter (in a regiment where the

average height was about 5' 8½") with hazel

eyes, brown hair, and a dark complexion. Giving

his residence as Cox Creek (which could refer to

the township or to the Cox Creek post office in

the western part of the township), he was paid

$25.00 of the $100.00 federal enlistment bounty

and a $2.00 premium. The $75.00 balance of the

bounty would be paid on honorable discharge.

The Company was mustered in at Dubuque on August

18, 1862 with a total of 99 men (officers and

enlisted). Another 17 would enlist subsequently

as new "recruits." Initial officers

were Captain William Crooke, 1st Lieutenant

Charles Heath, and 2nd Lieutenant Henry Howard.

The regiment was mustered in on September 9, 1862

at Dubuque where they received brief training at

Camp Franklin (formerly Camp Union).

Leaving Dubuque on September 16th, they went

first to St. Louis where they spent one night at

Benton Barracks. On night of the 21st they were

loaded on rail cars and, about midnight, left the

station. They traveled on the Atlantic and

Pacific Railroad through the night and the next

morning disembarked and made camp in Rolla. With

little to do while awaiting orders, regimental

bands often serenaded each other and men played

ball and other games. On October 15th, Charles

sprained an ankle while engaged in a

“friendly wrestle” with another

soldier.

The ankle sprain was his worst injury of the war

although, like most others, he had occasional

bouts of sickness, one serious enough to require

hospitalization. During the Vicksburg Campaign,

he participated in the May 1, 1863 Battle of Port

Gibson and was present during the May 16, 1863

Battle of Champion's Hill when the regiment was

held in reserve, something that was hard on the

men who could hear the sounds of battle and of

comrades in other regiments being wounded and

killed. "Those who stood there that

day," said Captain William Crooke,

"will surely never forget the bands of

humiliation and shame which bound them to the

spot, while listening to the awful crashes of

musketry and thunders of cannon close by."

Having not participated in the battle on the

16th, they were rotated to the front on the 17th

when Charles participated in the regiment's

assault on entrenched Confederates at the Big

Black River and had "his whiskers shot

off." During the assault the regiment had

seven men killed in action, eighteen fatally

wounded, and at least thirty-eight whose wounds

were not fatal. Among them was the regiment's

Colonel, Sam Merrill, who was very seriously

wounded in both thighs and fell on the field

while leading the assault. Charles survived the

assault without injury and, on May 22, 1863

participated in an assault on Confederate lines

at Vicksburg. Again the regiment had heavy

casualties: twenty-three killed in action, twelve

fatally wounded, and at least forty-eight

non-fatally wounded. Charles continued with the

regiment throughout the ensuing siege, a

subsequent expedition to and siege of Jackson,

Mississippi, and on January 7, 1864 was promoted

from Private to 7th Corporal. On August 1, 1864,

he was promoted to 6th Corporal and he held that

position during the regiment's final campaign of

the war, a campaign that ended with the

occupation of the city of Mobile, Alabama.

On July 15, 1865, they were mustered out at Baton

Rouge, Louisiana and, the next morning, boarded

the Lady Gay and started the long trip

up the Mississippi. About 8:00 a.m. on the 20th,

they went ashore at Cairo and went to the

“soldiers rest where a dinner was

waiting.” They then boarded rail cars and,

about 2:00 p.m., continued their journey north.

They received their final pay and were discharged

at Clinton on July 24th.

On September 22, 1869, Charles married Hannah Ann

Galer. They were married in Prairie du Chien, but

made their home in Osborne, Iowa, about six miles

south of Elkader, where Charles owned "a

finely cultivated farm of 156 acres."

Charles and Hannah raised a family of seven

children: Mary (born September 27, 1871), Charles

(born April 21, 1873), Clara (born April 27,

1875), Rose (born August 15, 1878), Elsie (born

May 13, 1880), John (born April 26, 1882), and

Robert (born November 16, 1883).

In 1878, Company D held a reunion in Strawberry

Point and Charles elected to attend. In 1883 he

joined the Elisha Boardman Post, Post 184, of the

G.A.R. in Elkader, he attended the regiment's

1911 reunion in Central City, and he served one

year as a School Director, but declined other

offices.

His mother died on March 16, 1886, and his father

nine months later on December 21st. Both were

buried in the Mederville Cemetery, 31220

Evergreen Road, Elkader.

In the fall, Charles often worked with H. K.

Johnston during the threshing season, but a lame

back eventually forced him to quit. On April 3,

1924, at age eighty-seven, Charles died of renal

and cardiac complications. Two days later, he was

buried in Mederville Cemetery, only a few minutes

from his home in Osborne. The following year, on

August 28, 1925, Hannah died and was buried with

her husband.

~*~*~

Robbins, William

Henry and Relief (French) Robbins were born in

Canada, immigrated to the United States, lived in

Ohio and Illinois, and, on October 14, 1855,

arrived in Clayton County where they settled in

Cox Creek Township about half way between Elkader

and Strawberry Point.

Their nine children were Malisa (born August 25,

1832), Susan also shown as Susanna (born April

25, 1834), Charles Henry (born June 25, 1836),

John (born January 27, 1838), William (born March

28, 1840, in Cuyahoga County, Ohio), Rachel (born

August 25, 1842), Relief (born August 28, 1850,

in Illinois), Joseph Emery (born February 28,

1852) and Lucy E. (born February 20, 1858).

As a boy, William was troubled with joint pain.

Some called it “inflammatory

rheumatism.” William Abbott, later a barber

in Manchester, recalled that William was once

treated by having “his feet and legs wrapped

with cloths saturated with turpentine and he was

sitting by the fire and the cloths caught

fire.” A doctor treated him, but William

“would scream with pain when they would go

to lift him up or turn him in bed.”

Abbott’s grandfather “took two-tined

pitchforks and wrapped rags around between the

tines of the forks and made crutches for him to

walk with. I never knew him after that to

complain of any pain or soreness in his joints or

to walk stiff or lame.”

Guns fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and

a conflict no one expected was fast approaching.

The War Department asked Northern states to

provide infantry or riflemen for a maximum of

three months, but the war escalated quickly and,

a year later, on July 9, 1862, Iowa Governor

Kirkwood received a telegram asking him to raise

five regiments as part of the President’s

call for 300,000 three-year men.

By then, Charles Robbins was twenty-six, John was

twenty-four and William was twenty-two. George

Peck, a farmer near Osborne, recalled that John

enlisted “but not being well & his

father objecting William took his place.” On

August 11, 1862, William and Charles were

enlisted at Cox Creek by Strawberry Point dentist

Charles Heath in what would be Company B of the

21st regiment of Iowa’s volunteer infantry.

They were ordered into quarters at Camp Franklin

in Dubuque on August 16th, mustered in as a

ninety-nine man company on August 18th and, with

nine other companies, mustered in as a regiment

on September 9th.

Crowded on board the steamer Henry Clay,

most left Dubuque on September 16th, went

downstream to St. Louis and then, by rail,

traveled to Rolla where they spent the next month

of their service. From Rolla, they walked to

Salem, Houston, Hartville, back to Houston and

then south to West Plains where they arrived on

January 30, 1863, after a difficult march in the

mid-winter ice and snow. From there they moved to

the northeast, passed through Iron Mountain,

Ironton and Pilot Knob, and, on March 11th,

arrived in Ste. Genevieve where they camped on a

ridge north of town.

On April 1st, Companies B, C and G boarded the Ocean

Wave and started downstream. The other seven

companies traveled on different transports. The Ocean

Wave reached Memphis on April 3rd, laid over

for three days and resumed the trip on the 6th.

That evening the men debarked at Milliken’s

Bend where General Grant was assembling a large

army at the start of the North’s latest

campaign to capture Vicksburg. On the 12th, they

began what would be a difficult walk south,

sometimes on roads but other times struggling to

make their way through swamps and across bayous.

On April 30th they crossed the river to

Bruinsburg and on May 1, 1863, William

participated with his regiment in the Battle of

Port Gibson. He was present when they were held

in reserve during the Battle of Champion’s

Hill, and participated in a May 17th assault at

the Big Black River and a May 22nd assault on

Confederate lines at Vicksburg. General Grant

then decided on a siege with the 21st Infantry

stationed opposite the railroad redoubt, but the

arduous duty during the past two months had been

hard on William.

A robust, healthy, man before the war, he was now

exhausted. Christian Maxson (a postwar merchant

in Edgewood) recalled that during the siege

William “was on guard I went out to see him

and while I was standing talking to him his gun

fell out of his hand and he sat down and placed

his hand over his heart, and I asked him what was

the matter with him and it was quite a spell

before he answered me and then he said that there

was something the matter with his heart. He did

not say how it affected him only that he felt

smothering - could not get his breath.” In

June, Charles took his brother to the division

hospital where William was admitted. George Crop

(a postwar farmer near Sand Springs) was in the

hospital at the same time and recalled that one

day, William, “got up and started to walk

from his bunk and having taken two or three steps

he fell and I thought he was dead, but they

picked him up and he remained unconscious for as

much as fifteen minutes."

Abe Treadwell and Myron Knight (both farmers near

Edgewood) recalled that it was about this time

that William was “moon-struck” and

couldn’t see after dark. They called it

“moon-eyed.” Never one to shirk duty,

William traded with others so they did his duty

at night and he did their duty during the day.

Christian Maxson said that, during the Mobile

campaign in the spring of 1865, “I was on

guard at a house to keep the boys from tearing it

down when William Robbins came up to me to give

me some orders and he dropped right down on the

porch beside a post and placed his hand over his

heart and fell over backwards and seemed to lose

consciousness. I called for some water and

sprinkled in his face and he revived and I asked

him whether he was troubled a great deal with

those spells and he said he was but that that was

the hardest spell he had ever had. He said that

it would be the death of him yet.”

Despite his problems, William was never one to

complain. A private at enlistment, he was a 2nd

Corporal when he was mustered out with the other

original enlistees on July 15, 1865, at Baton

Rouge. On the 24th, they were discharged from the

military at Clinton. Charles recalled that,

“on the 26" day of July, 1865, at

Dubuque, Iowa, while on our way home about 4

o’c in the evening he and I went to the R.R.

depot to take train for Manchester Ia on our way

home and while at depot William Robbins suddenly

placed his hand upon his breast and said,

‘God Fifer, if this old thing sticks to me I

won’t have but a few days to stay after I

get home.’ I was often called fifer in the

army. I replied to him that we would have good

times yet and tried to get his mind off from his

malady. I remember this incident vividly for I

was startled at his action knowing that he was

liable to drop away suddenly. I remember this

date for we arrived home on the 27" day of

July 1865.”

Only a month later, William and his father were

busy harvesting. While others were “carrying

sheaves,” William “took the grain

cradle and cradled a short time and blistered his

hands and suddenly he dropped the cradle and

placed both hands to his breast.” Despite

their concerns, others tried to lighten the mood

by making fun of his blistered hands. The next

fall he worked for Henry Long, Henry Walker and

Dave Courtman on their farms, but often had to

“stop work for a few moments” to catch

his breath. William Abbott recalled that, one

time, “after we quit harvesting and while on

our way home and crossing a piece of new breaking

(being very rough) he was taken again and dropped

some thing he was taking home and put his hands

to his breast.” It happened again in the

fall of 1867 when he was “attempting to load

a rather heavy log;” the horse started,

William got angry and immediately “had a

spell.” True to form, he sought no medical

treatment and, unlike most others with

disabilities they attributed to their military

service, did not apply for an invalid pension.

On April 5, 1868, William married Nancy Scovel in

Littleport. For the next year and a half they

made their home near Osborne and William

continued working with others, traveling around

“threshing in all kinds of weather and

sleeping under the machine at night.”

William Carpenter had served with William and

recalled that, “about 5 years after our

discharge Wm. Robbins was threshing. I think at

my fathers place and I was helping father.

Robbins was oiling machine when suddenly he

stopped straightened up and threw his head and

shoulders back and gasped like. I asked him what

was the trouble and he leaned against machine and

said it seemed as though he would choke to death

and there was a bad feeling in his chest.”

A. W. Smith said William worked for him in 1876.

“In haying of that year I assisted Mr.

William Robbins in drawing hay. He was pitching

from load. I was mowing it away when suddenly

without saying a word he sat down upon the load

and appeared in distress I asked him what the

trouble was and he placed his hand upon his

breast and said he had trouble of the heart and

had such spells frequently. He was a person who

said but very little, was very quiet and of good

habits and good reputation.” Fred Peet said

he and William were pitching hay when William

“opened his shirt and showed me his chest

and I noticed his heart was throbbing for dear

life and I told him to quit work. I asked him how

long he had been troubled in that way and he said

ever since he had been in the army.”

William and Nancy had four children: Saphronia

born December 25, 1868, Effie May born June 9,

1870, William H. R. born July 14, 1872, and

Jennie born July 4, 1875. Edgewood’s Lewis

Blanchard was the family doctor, but said William

was “opposed to taking medicine or being

treated by a physician” and “was always

in a great hurry when at my office.” As

William continued grubbing, chopping wood,

breaking prairie, threshing and doing some

carpentry work, his attacks became more frequent.

He had trouble sleeping and often had to sit up

for most of the night.

On February 2, 1882, “he was away cutting

some brush and seemed to be unusually tired at

night and did not sleep any scarcely.” The

next morning he chopped wood and “after his

dinner was sitting at the table reading and

I,” said Nancy, “was sitting with my

back to him and after a time he asked me what

time it was and I said it was three o’clock.

He then said it was time for him to go to work.

That was the last he ever said.” Turning

around, Nancy saw William’s “head

leaning forward over his chest.”

Forty-one-year-old William was dead. He is buried

in Edgewood Cemetery where a G.A.R. marker stands

next to his government-issued stone.

Claiming that his death was service-related,

Nancy was working as a “washerwoman”

when she applied for a widow’s pension, but

proving her claim was difficult. William had been

hospitalized at Vicksburg, but there was no other

military record reflecting medical problems and

he had served without complaint for the full term

of his enlistment. Comrades and friends signed

affidavits attesting to his health before, during

and after the war, but the pension office

wasn’t convinced. Special examinations were

ordered and pension examiners took depositions in

Edgewood, Osborne, Manchester, Sand Springs,

Clarksville and Brush Creek and even in Stockton,

California; twenty-four depositions in all. It

took eight years, but a pension was finally

approved retroactive to the date of

William’s death.

William’s parents both died in 1886 and are

buried in Mederville Cemetery as is his brother,

Charles, who died in 1924. William’s

daughter, Saphronia, died in 1891 and was buried

near her father. Nancy Robbins continued to live

in Edgewood until her death on October 3, 1921.

She, like her husband and daughter, was buried in

Edgewood Cemetery. Effie married Christian Maxson

who had served with her father. She died in 1947

and also was buried in Edgewood Cemetery. Her

brother, William, died in 1933 and is buried in

Manchester’s Oakland Cemetery. Jennie was

the last of the Robbins’ children to die.

She had worked as a school teacher, cared for her

mother as Nancy got older, never married and

eventually moved to Los Angeles where she died on

December 22, 1953.

~*~*~

Robinson, David H.

David Robinson was born in Highgate, Vermont, in

1826 or 1827. More than 450 miles to the

southwest, Sarah (“Sally”) Howard was

born on June 1, 1835, near Mayville in Chautauqua

County, New York. They were married at the home

of David and Didama Wood in Chautauqua County on

July 1, 1852. A daughter, Viola Almira Robinson,

was born in 1853 in Pennsylvania and a son,

Charles A. Robinson, was born in 1855. By the

following year the family of four was living in

Highland Township, Clayton County, Iowa, where,

on January 25, 1862, a daughter, Carra May

(“Carrie”) Robinson, was born.

By then the Civil War was more than nine months

old and thousands of men had lost their lives. On

April 6, 1862, Union soldiers were surprised when

attacked in Tennessee. The two-day Battle of

Shiloh awakened those in the west to the severity

of the war as Iowa’s hospitals were soon

filled with the sick and wounded brought north on

hospital ships. On July 9th, President Lincoln

called for 300,000 more volunteers with Iowa to

raise five regiments. Despite the approaching

fall harvest, the volunteers came quickly. David

enlisted at Elkader on August 14th in what would

be Company D of the 21st Iowa Volunteer Infantry

with Sam Merrill, a McGregor banker and merchant,

as Colonel. David was described as being a

thirty-five-year-old farmer, 5' 6¼” tall

with brown hair and dark eyes.

Company D was ordered into quarters at

Dubuque’s Camp Franklin where they were

mustered into service on August 22, 1862. On

September 9th, ten companies were mustered in as

a regiment and on the 16th they left for war.

Crowded on board the Henry Clay and two barges

tied alongside, they went downstream and, after a

night on Rock Island, resumed their trip but had

to debark at Montrose due to low water levels.

From there they took a train to Keokuk, boarded

the Hawkeye State, reached St. Louis on the 20th,

left by rail the next day and arrived in Rolla,

Missouri, on the 22nd. Company Muster Rolls were

taken bimonthly and indicated the presence or

absence of the soldier as of the last day of the

period. David was “present” on October

31st at Salem, December 31st at Houston and

February 28th at Iron Mountain but, in each

instance, was marked “sick in

quarters.”

They reached the old French town of Ste.

Genevieve on the Mississippi River on March 11th

and made camp on a ridge north of town. By then,

General Grant was planning a campaign to capture

the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, a city

that, together with Port Hudson, kept that

segment of the river out of Union hands and

permitted Confederate soldiers and supplies to

cross unimpeded. The Ste. Genevieve regiments

were transported downstream to Milliken’s

Bend where Grant’s 30,000 man army was being

organized. Assigned to a corps under General John

McClernand, the regiment started a movement south

along the west side of the river - walking on

muddy roads, wading through swamps and being

transported over numerous bayous.

David Robinson was with the regiment as they

passed Richmond, Cholula and New Carthage and, on

April 23, 1863, when they camped on John

Perkins’ Somerset plantation. The

able-bodied continued their march, but the April

30th muster roll said David had been admitted to

a division hospital at Somerset. From there, he

was transported north for better treatment and

was hospitalized at Jefferson Barracks in St.

Louis when he died on August 4th from the

debilitating effects of chronic diarrhea. David

and several other members of the regiment are

buried in the National Cemetery at the barracks.

A week after her husband’s death, Sally

appointed attorney Thomas W. J. Long to go to St.

Louis to retrieve any personal effects and, on

the 19th, Thomas signed a receipt for a gold pen

and case, a wool blanket, a vest, a pair of

socks, a blouse, a hat, a jackknife, a pair of

boots, two pairs of pants and $29.05 cash.

The following month, on September 23, 1863, Sally

married thirty-year-old widower George Redhead at

the home of Jacob and Rohana Howard in Pony

Hollow near Elkader. George had been married to

Ann Rowe but, in 1861, in a span of fewer than

six months, Ann and both of their children

(one-year-old and two-month-old sons) died. All

three are buried in Garnavillo Cemetery.

Charles Robinson also died young, but Viola and

Carra, their mother and her new husband soon

“settled on a farm they had purchased two

miles south-west of Postville.” Due to her

remarriage, Sally was not eligible for a

widow’s pension but, on November 23, 1863,

she signed an affidavit requesting a pension for

“Viola and Carra May Robinson.” Her

request was supported by David’s captain,

Elisha Boardman (who recalled that David had

become sick due to exposure and hardships

“and never done duty afterwards”) and

by others who signed affidavits attesting to

Sally’s marriage to David and the birth of

Viola and Carra. A monthly pension of $8.00 was

granted retroactive to the day after their

father’s death. Two years later, saying she

was a resident of Grand Meadow Township in

Clayton County but with a post office address in

Postville, Sally applied for an increase which

was soon granted.

On October 5, 1864, George Redhead enlisted in

the military. He was mustered in as a new recruit

in Company C of the 13th Regiment of Iowa’s

volunteer infantry and, for a second time, Sally

“was put to the task of managing the farm

and caring for the home while awaiting the return

of her husband.” He was mustered out at

Louisville, Kentucky, on July 21, 1865, and

discharged at Davenport on the 29th.

George resumed his farming career, but needed

frequent medical treatment. Dr. B. H.

“Doc” Hinkly, a physician in Clermont,

recalled that he had first treated George on

August 9, 1865, only eleven days after his

discharge. George was then in a “very bad

condition being reduced very low & his mind

somewhat defective his Diorrhoea had reduced him

to the lowest.” Dr. William Lewis of

Clermont treated George in 1883 and “gave

him office advice for an attack of acute

albuminuria.” George’s “urgent

symptoms gave way readily, but convalescence was

slow, and he was in a debilitated

condition.” Dr. Luther Brown of Postville

also treated George and noted that “he

successfully conducts a large farm.” James

Roll who did George’s blacksmithing recalled

that George was “a very stout active

man” before enlisting, but was

“frequently confined to his bed” after

being discharged. H. D. Angell said George was

“not expected to live” when he first

came home.

Despite his health issues, it was not until

February 3, 1886, that George finally applied for

an invalid pension. Indicating he was a resident

of Grand Meadow Township, he said he was

suffering from chronic diarrhoea incurred in the

military. Government records confirmed his

service and illness, but did not reflect any

diagnosis or medical treatment. A Board of

Pension surgeons said he appeared well-nourished

and muscular and no pension was awarded. Like

most veterans, George persisted. There were more

affidavits and another examination and finally,

on April 18, 1887, a certificate was issued

providing for $8.00 per month.

In addition to the three children (Viola, Charles

and Carra) that she had with David, Sally had

another four (George Lincoln, Lillian B., Anna

and Sadie Grace) with George.

Carra married Hiram Booth on August 26, 1886, but

the next year became ill and Sally went to care

for her. Sally returned home on December 10th

thinking Carra was improving but, later that

month, Carra died and was buried as “Carrie

M. Booth.” Hiram then married her

half-sister, Lillian.

Sadie Grace Redhead died in 1912 and was buried

as “Sadie G. Eckard.” Her father,

George Redhead, died on January 3, 1914.

Sally’s oldest daughter, Viola, married

twice, died on February 16, 1926, and was buried

as “Viola A. deEnos.” Sally died on

December 12, 1928, while living with Anna at1461

West Lake Street, Minneapolis. Sally, Carra,

Viola, Sadie and George are all buried in

Postville Cemetery. Sally was survived by three

children from her second marriage - George

Lincoln Redhead, Lillian B. (Redhead) Booth and

Anna (Redhead) Spurling.

~*~*~

Robinson, John J.

John J. Robinson was born in Richland County in

upstate New York. By 1859 he was living in

Colesburg, Iowa. A year later he was in Buffalo

Grove. In January 1862 he moved to Strawberry

Point where, on August 13, 1862, he was enrolled

by William Grannis in what would be Company D of

the state's 21st regiment of volunteer infantry.

The Muster-in Roll said he was a

twenty-eight-year-old farmer with blue eyes,

black hair and a dark complexion.

On August 22nd, the company was mustered in at

Camp Franklin in Dubuque with a total complement

of ninety-seven men (officers and enlisted). On

September 9th, ten companies were mustered into

federal service as a regiment and, on a rainy

September 16th, those able to travel walked

through town and, at the foot of Jones Street,

boarded the sidewheel steamer Henry Clay

and two barges tied alongside and started south.

Downstream they transferred to the Hawkeye

State and, about 10:00 a.m. on the 20th,

they arrived in St. Louis where they spent one

night at Benton Barracks before traveling by rail

to Rolla. They camped most of the time a few

miles southwest of town where there was good

spring water, but on October 18th started the

first of many long marches. The next day they

arrived jn Salem where, on the 31st, John was

"sick in quarters." From Salem they

walked to Houston and then Hartville where they

were dependent on supplies brought by wagon train

from the railhead in Rolla.

On November 24th, teamsters and guards taking

supplies to Hartville camped for the night along

Beaver Creek. That evening, some were tending to

the horses, others were finishing dinner and some

were foraging in the nearby woods when they

were.attacked and quickly overwhelmed. One man

was shot in the chest and killed. Two others were

mortally wounded. Sixteen men, three of whom had

been wounded, were taken prisoner and paroled.

Among the wounded was John Robinson who was one

of the guards. John sustained a gunshot wound to

"the left side of the crown of the

head" (the "left parietal

eminence") and was "rendered

insensible." He was taken to the regimental

hospital in Hartville where, said Strawberry

Point's Joseph Baker, "I washed his wound

and did all I could for him."

John was with the regiment when it moved back to

the more secure confines of Houston, but was

still convalescing and remained behind when the

regiment started for West Plains on January 26th.

Several weeks later he caught up but was sick

"in quarters" at Iron Mountain and then

hospitalized for 'febris remittens"

(malaria) and pneumonia. He returned to duty on

July 19, 1863, duringthe brief siege at Jackson,

Mississippi, and was with the regiment when it

moved farther south and camped at Carrollton.

There, on September 5th, he was granted a

thirty-day medical furlough to go north. He

reached his Clayton County home on the 18th, but

was late returning to the regiment. "I left

home Feb 3d 1864 to report to my Company and

Reg't was detained at Dubuque Iowa five days

waiting transportation which I received from

Provost Marshal at Dubuque Iowa to report at

Davenport Iowa where I arrived about the 9th of

Feb 1864 and was detained there by order of

Surgeon in Charge until the 12th Clay of March

1864, I there received transportation and

reported to my Company March 26th 1864" at

Matagorda Island, Texas. He said he had, for a

long time, been "unable to travail and

regularly forwarded Surgeon's certificates

stating that such were the facts."

Lieutenant William Grannis confirmed receipt of

the certificates from Dr. Clark Rawson and John

was reinstated without loss of pay or allowances.

John was able to maintain his health during the

balance of the regiment's service on the Gulf

Coast of Texas and, subsequently, in southwestern

Louisiana, on the White River of Arkansas and in

Memphis. On January 17, 1865, the regiment was

camped near New Orleans on low ground at Oakland,

the Kenner family's old sugar plantation, when

George Brownell said he and John Robinson

"took a walk back acrost the plantation to

the woods distance two miles we got a lot of

boards together and built a little raft and run

it near camp and then got team to haul it up for

us. We gave our officers the moste of it to build

a flour up." On the 22nd, Emerson Reed

joined them when they "took a long walk in

the forenoon."

In February, they were transported down the

Mississippi and eastward across the Gulf to

Dauphin Island on the west side of the entrance

to Mobile Bay. On March 19th, after crossing to

Mobile Point, they started a very difficult

movement north along the east side of the bay

and, said Lieutenant Cooley, "the command

suffered terribly from exposure, rain and

mud." Already suffering from a "lame

back," John was among thousands of men

working, sometimes in torrential rain, to drag

trees and logs through swamps and marshes to make

many miles of corduroy roads. Often, said George

Crooke, "the first trains passing over would

bury the logs out of sight, and the process had

to be repeated two or three times." John

caught a severe cold and the hard work affected

his lungs, but he continued on duty throughout

the Mobile campaign and subsequent service along

the Red River in Louisiana where George Brownell

said he, John Robinson, Emerson Reed and Duane

Grannis "went hunting for bees but did not

have any luck."

They were mustered out of service at Baton Rouge

on July 15, 1865, and discharged at Clinton on

July 24th. Initially, John went to Brush Creek

and lived with John and Mary Carothers

"during the fall and winter and during the

year 1866" and the men worked together

"at the business of burning lime." John

also worked as a farmer but, in 1870, he, Frank

Billgham, and John and Mary Carothers moved to

the Dakota Territory where they lived near

Springfield.

On December 15, 1873, John applied for a

government pension. Pensions at that time

required a veteran to show he was, to some

extent, unable to perform manual labor due to a

service-related disability. Saying he was a

healthy man before the war, John referred to the

head wound he sustained eleven years earlier and

said he was now "frequently attacked with

vertigo & partial loss of vision." John

Carothers recalled that they had worked together

"wood choping shoveling dirt and in the

hearvest field" before the war, but now John

was "troubled with lame back and lung and

throat disease." Surgeons in West Union

found a scar and 'some indentation of the

bone" and felt John was entitled to a

pension.

In an April 1874 affidavit, John declared

"that he is married; that is wife's name was

Clarinda Smith, to whom he was married at

Taylorsville Iowa" and said he was now

"almost wholly disabled from obtaining his

subsistence from manual labor." In

subsequent affidavits (all signed by mark), he

said he also had a lame back and kidney problems

due to a cold Missouri winter during the first

year of his service. Several comrades signed

supportive affidavits and Gilbert Cooley, then

living in Strawberry Point, recalled the Beaver

Creek attack and that during the winter John

"became lame in his back with kidney

affection." The Pension Office investigated

the claim, but made no decision and, in July,

1877, John moved back to Brush Creek. In 1879, he

again applied for a pension and, this time, also

referred to the difficult Mobile campaign when he

said he "contracted lung and throat disease

from which he has never recovered. "In an

1881 affidavit, John's father, Thomas Robinson,

said John was healthy before the war

("always able to do any kind of hard labor:

such as choping wood, working in the hearvest

field, or working in the ground with a

shovel"), but not after being discharged

with a cough, shortness and lame back (when he

was unable "to do hard manual labor and more

than half the time has been unable to do any kind

of labor more than light chores").

Subsequent to his discharge, John said "that

he doctored himself, was poor, had no money to

pay doctor bills, that his mother was living

then, that she was a good nurse and made remedies

in the shape 'of salves and liniments, that he

used them for his lame back, cough, throat and

lungs." In the Dakota Territory he was

treated by Dr. Thomas Eagle and in Brush Creek by

Dr. T. M. Sabin. Dr. Sabin said he had become the

family physieian soon after John returned from

the Dakota Territory. Suffering from lumbago and

chronic bronchitis "which almost totally

disabled him," John was sometimes

"confined to the house for several

days." A certificate of October 11, 1880,

awarded $2.00 monthly, an amount later increased

to $8.00, $12.00 and finally to $30.00 he was

receiving when he died on January 18, 1904. John

Robinson is buried in Arlington Cemetery in

Fayette County as are John and Mary Carothers.

~*~*~

Rogers, Jabez S. 'Jabe'

Jabez S. Rogers was born in Preble County, Ohio,

in about 1830 and married Sarah J. Reeves (aka

Reeve) who had been born in Ohio in about 1839.

Internet sources indicate their first three

children, all born in Iowa, were Fremont (about

1859), Almina (about 1860) and Heenen born in

McGregor on September 9, 1861, when Iowa's 1st

Infantry was already in the field. With President

Lincoln having called for 300,000 more men to

fight an increasingly devastating war, thirty-two

year old Jabez, then working as a carpenter, was

one of many in Clayton County who answered the

call. On August 12, 1862, he was enrolled at