Maloney,

Jerry

Jerry Maloney was born in County Cork, Ireland,

emigrated to the United States and, on July 25,

1856, married Mary Hennessy in Little Falls,

Herkimer County, New York. During the next

several years, tensions escalated over the

“slavery question,” John Brown attacked

the armory at Harpers Ferry, and Southern militia

fired on Fort Sumter. Before long, the country

was embroiled in war. On July 9, 1862, with the

war escalating, Governor Kirkwood received a

telegram asking him to raise five regiments as

part of the President’s call for 300,000

three-year men. If the state’s quota

wasn’t raised by August 15th, it "would

be made up by draft." Jerry Maloney was one

who answered the call.

On August 7, 1862, Jerry was a forty-year-old

farmer when he enlisted at Strawberry Point in

what would be Company B of the state’s 21st

regiment of volunteer infantry. The company was

mustered into service on August 18th and the

regiment on September 9th, both at Camp Franklin

in Dubuque. A “Book of Irish Americans”

by William D. Griffin says 144,221 men of Irish

birth served in the Union Army, with 1,436

enlisting from Iowa. In the 21st Infantry, Jerry

Maloney was one of at least forty-five men

mustered in on the 9th who gave Ireland as their

place of birth.

Jerry was described as being five feet, five

inches, tall with blue eyes, brown hair, and a

light complexion. Crowded on board the Henry

Clay, a sidewheel steamer with two barges

lashed to its side, they left Dubuque on a rainy

September 16th.

Muster rolls were taken bimonthly and Jerry was

reported “present” on all initial rolls

as they saw service in Missouri - Rolla, Salem,

Houston, Hartville, West Plains, Ironton, Iron

Mountain, and Ste. Genevieve. At Ste. Genevieve

they boarded the Ocean Wave on April 1,

1863, and started downstream to Milliken’s

Bend where General Grant was organizing a massive

army with a goal of capturing the Confederate

stronghold at Vicksburg. Assigned to the 13th

Corps under General John McClernand, they left

the Bend on April 12, 1863, and started a slow

movement south through swamps and bayous on the

west side of the Mississippi River.

On April 30, 1863, the army started to cross the

river from Disharoon’s Plantation on the

west bank to the Buinsburg landing on the east

bank. Soon after going ashore, the 21st Iowa,

guided by a former slave, became the point

regiment for the entire army as they headed

inland on a dirt road. On May 1, 1863, Jerry

Maloney participated with his regiment in the

Battle of Port Gibson in which the regiment had

three men fatally wounded and thirteen wounded

less severely. He also was with the regiment

during the Battle of Champion’s Hill on May

16th when they were held in reserve by General

McClernand. .

Having not participated in the battle on the

16th, they were rotated to the front on the 17th

and, with the 23rd Iowa, led an assault on a

Confederate force hoping to keep the railroad

bridge over the Big Black River open. The

three-minute bayonet charge was successful, but

seven members of the regiment were killed in the

charge, eighteen were fatally wounded, and

thirty-eight were wounded non-fatally. Among the

most seriously wounded was the regiment’s

Colonel, Sam Merrill, who suffered serious wounds

to both thighs and fell on the field, but later

became a post-war Governor of Iowa.

Five days later, Jerry Maloney participated with

the regiment in an assault on the Confederate

lines at Vicksburg when the regiment suffered its

heaviest casualties of the war: twenty-three

killed in action, twelve more with fatal wounds,

forty-eight with non-fatal wounds, and four

captured. This assault was unsuccessful and a

lengthy siege followed. Jerry was present the

entire time, but the siege took its toll. On

August 14, 1863 he was granted a furlough on a

Surgeon’s Certificate, although Jim Bethard,

a comrade in Company B, wrote that Jerry had

actually left for home the previous week. After

receiving a thirty-day extension, Jerry started

back to the regiment, reported in at Cairo on

October 9th, and reached the regiment at Camp

Pratt near New Iberia, Louisiana, on November 4,

1863.

His health restored, Jerry was marked

“present” for two months of service in

southwestern Louisiana, and during its extended

service from November 1863 to June 1864 along the

Gulf Coast of Texas. After returning from Texas,

the regiment was stationed at Morganza,

Louisiana, performed service along the White

River of Arkansas and, about daylight on the 28th

of November, arrived in Memphis. Again, Jerry was

not well. Suffering from chronic diarrhea, he was

admitted to the city’s Overton U.S.A.

General Hospital on December 15, 1864. Diarrhea

plagued men and women on both sides, "and

every day takes a greater number to the hospitals

than are returned," said one. Men tried to

clean cooking utensils and wash away dirt, but

water was rarely hot. Drinking water was often

contaminated and food fried in heavy grease

caused one surgeon to complain of “death

from the frying pan.” Intestinal infections

were rampant, led to malnutrition, anemia and

increased susceptibility to other diseases

resulting in extreme dehydration, up to fifty

percent weight loss, and an estimated 50,000

deaths in the Union army, at least sixty-five in

the 21st Iowa. Medical treatment included Epsom

salts, castor oil and opium. Some doctors thought

quinine or calomel would help and all recommended

fruits and vegetables if available. After

hospital treatment in Memphis, Jerry was able to

rejoin the regiment at Spring Hill, Alabama, on

April 19, 1865, and was present when they were

mustered out at Baton Rouge on July 15.

After the war, he worked as a laborer at a

variety of jobs including the rail line near

Winthrop, Buchanan co., but his war-related

illness continued and gradually grew worse.

Finally, on March 19, 1874, giving his age as

forty-nine and signing with an “X,” he

applied for an invalid pension. By then, he said,

he was a resident of Alden in Hardin County and

felt he was “totally disabled from obtaining

his subsistence from manual labor.” With

many thousands of veterans seeking federal

pensions, applications took a long time for

claimants to prove and the government to

investigate. Jerry secured affidavits from

friends who knew him before and after the war,

from doctors who had examined him, and from Salue

Van Anda, the regiment’s former Lieutenant

Colonel. Eventually on June 12, 1878 a

certificate was issued entitling Jerry to $6.00

monthly, paid quarterly.

Five months later, he applied for an increase.

His health, he said, had worsened since he first

applied more than five and a half years earlier.

He was examined by doctors in Eldora, they

submitted their report, and Jerry’s pension

was increased to $8.00. Eventually, Jerry

returned to New York where he had married his

wife so many years earlier. He was living in The

New York State Soldiers & Sailors Home in

Bath, New York, when he died on October 17, 1892.

He is buried in the Bath National Cemetery.

~*~*~

Mather, Darius

The first of five sons born to Southworth and

Philena (Rice) Mather, Darius was born on

December 15, 1831, in Union County, Ohio. On

March 24, 1853, in the town of Dover, Darius and

his cousin, Amanda H. Mather, were married. Their

children included Florence born in 1856, Francis

in 1857, Delmer in 1859 and Abbie in November1860

when that fall’s election campaigns were

well underway.

By then they were living in Iowa and only a month

earlier South Carolina’s governor had said

his state would secede if Lincoln were elected

but the Clayton County Journal discounted

the threat as one routinely made every four

years. “This cry was invented only to

frighten the people into voting for the

Democratic candidate” it said, but Lincoln

was elected and South Carolina did secede. Still,

the Journal wasn’t worried. “We hope

however our readers will not become too excited

over this, because it is not worth while. There

are men enough in Pennsylvania alone to subdue

South Carolina without the aid of Iowa

volunteers.” On April 12, 1861, General

Beauregard’s cannon fired on Fort Sumter.

By the fall of 1862, with thousands of men having

died, President Lincoln called for another

300,000 volunteers with Iowa given a quota of

five new regiments. If not met by August 15th,

the difference would be made up by a draft.

Governor Kirkwood was concerned. The war was more

serious than anticipated, initial military

enthusiasm had subsided and disloyal sentiment

was strong in some parts of the state but he

assured the President "the State of Iowa in

the future as in the past, will be prompt and

ready to do her duty to the country in the time

of sore trial. Our harvest is just upon us, and

we have now scarcely men enough to save our

crops, but if need be our women can help."

Darius was a thirty-year-old carpenter when he

was enrolled in Grand Meadow Township on August

14, 1862, in what would be Company E of the 27th

Iowa Infantry. Two weeks later he was appointed

Fife Major. The regiment was mustered into

service on October 3rd at Dubuque’s Camp

Franklin and on the 11th was ordered to Minnesota

where six companies saw brief service while the

other four went south to Cairo where all ten

companies were later reunited. On November 20th

they left for Memphis.

Darius was reported present on the December 31st

muster roll at Lexington, Tennessee, and the

February 28, 1863, roll at Jackson, Tennessee,

but on April 20th was sick and did not rejoin the

regiment until May 3rd. He was then reported

present on the bimonthly roll for the period

ending June 30th but on July 29th was granted a

furlough. He was still shown as absent on the

August 31st roll but was present on the October

31st and December 31st rolls when the regiment

saw service at Devall’s Bluff, Arkansas, and

along the White River before moving to Memphis.

On January 28, 1864, they were ordered to

Meridian, Mississippi, but Darius was ill with

erysipelas, a bacterial infection that caused

many deaths during the war but was treatable with

proper medication. On February 9th, Edward

Wilhelm, a hospital steward in a convalescent

camp, asked that Darius be admitted to a general

hospital due to the camp “not being supplied

with medicines to treat such cases.” The

steward’s request was granted and Darius was

admitted to General Hospital No. 3 at Vicksburg

on March 8th. He was still there on the 30th when

the illness caused his death. His clothing and

other personal items including a silver watch and

gold chain were stored at the hospital for

disposal by a Council of Administration.

Of four Mather brothers who served in the war,

Darius was the third to die. Esquire had died of

chronic diarrhea while home on furlough in 1863

and is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Lansing. John

had also died of chronic diarrhea in 1863. He and

Darius are buried not far from each other in

Vicksburg National Cemetery. Their younger

brother, Sterling, would die in 1866, less than a

year after being discharged from the military.

On August 9, 1864, while living in Clermont,

Amanda signed an application for a pension for

herself and her four children then aged three,

five, seven and eight with William Cowles of West

Union as her attorney but no apparent action was

taken. Nine months later, on May 15, 1865, still

living in Clermont and still with William Cowles

as her attorney, Amanda signed another

application seeking a pension for herself and her

four children. The application was received by

the pension office on May 20th and a month later

was approved retroactive to the day after

Darius’ death at $8.00 monthly for Amanda

and an additional $2.00 monthly for each of her

children that would continue until their

sixteenth birthdays.

On April 23, 1866, Amanda filed a petition with

the Clayton County circuit court asking that she

be appointed as guardian at law for three of her

children. Francis was not mentioned and may have

died after the original application was filed.

The petition was supported by Dr. H. B. Hinkly

who signed an affidavit confirming the names and

birth dates of the children and indicating

“that he was the attending physician”

for all of their births.

On September 5, 1868, in West Union, Amanda

married Jabez Carpenter Rounds, a widower whose

first wife had died in 1864. Due to her marriage,

Amanda was no longer entitled to a widow’s

pension but the children’s pensions would

continue.

Amanda died on June 22, 1874 and Jabez on

February 6, 1892. They’re buried in Eno

Cemetery, Clayton County.

~*~*~

Mather, John H.

During the 1850s, several families, many related,

emigrated from Ohio’s Union County to

Clayton County. Among them were Joel and Sarah

Rice and their children - James, Caroline,

Robert, George, Marshal and Tero. Also emigrating

were Southworth and Philena (Rice) Mather who had

twelve children - three boys who died in infancy,

three girls and six more boys (Fortner, Daniel,

Darius, John H., Esquire aka

"Squire"and John Sterling aka

"Sterling"). Moving by himself was Jim

Bethard who left his father's home near Dover to

follow - and marry - Caroline (he called her

“Cal”) Rice in Clayton County.

Of these, the Rev. Fortner C. Mather was the

first to move when, in 1853, he became pastor of

a Methodist Episcopal Church in Clayton County.

During the Civil War, Jim Rice, John Mather and

Jim Bethard were among more than 140 enlistees in

Iowa’s 21st Infantry who gave Ohio as the

place of their birth. Darius Mather joined the

27th Infantry while Squire and Sterling Mather

joined the 9th Infantry. Robert Rice joined the

9th Cavalry and George Rice the 9th Infantry. As

a result, Caroline had a husband, three brothers

and at least three cousins serving with the Union

Army.

John H. Mather was born near Marysville, Ohio on

April 17, 1841 and accompanied his parents and

siblings to Iowa. After Southworth's death in

Castalia on March 30, 1861, his sons took

responsibility for Philena's well-being but, when

the President called for 300,000 more volunteers,

Squire, Sterling, John and Darius answered the

call.

John, Jim Rice and Jim Bethard enlisted together

on August 11, 1862, giving Grand Meadow as their

residence. On 18th they were mustered into

Company B and on September 19th into Iowa’s

21st regiment of volunteer infantry. All three

were farmers, unfamiliar with the military. On

September 16th, after brief training at

Dubuque’s Camp Franklin, they boarded the

181' long sidewheel steamer Henry Clay

and climbed to the hurricane (top) deck while

others crowded together on the lower decks and

two barges tied alongside. The big wheel began to

turn and they left for war while friends and

relatives waved and cheered.

Jim Bethard wrote often to Cal and usually

mentioned her brother James and cousin John:

09/16/1862 From Rock Island, Illinois. "Jim

and John and I slept on the hericane deck last

night.”

10/15/1862 From Rolla, Missouri. "John

Mather got a letter from Squire and Sterling a

few days ago.”

11/15/1862 From Hartville, Missouri. "John

Mather received a letter this evening. from

Sterling . . . . Jim and John and I have

discovered that it [tobacco] is a nautious weed

and we therefore abstain from the use of

it."

12/07 /1862 From Houston, Missouri. “John

Mather has had a spell of the yellow jaundice but

is about well now . . . . As I have nothing of

importance to write I will give way to our friend

John."

When they left Iowa, the daughter of Jim and Cal

was three months old. As Jim said in his letter

of December 7th, he gave way to a jovial John who

added a personal note to Cal:

Dear Cousin I take this

present opportunity to address you Well Cal

how-de-do how are thee and thy little Babe I

am well all tho I had the yuller gandice

purty bad but have ... well I guess that is a

nough of that last night James B & I

slept together and we had a good old sleep we

got us a pair of blankets & we had a pair

before we have 4 blankets between us we sleep

very warm in our little tents

well Cal I have good old times with your Jim

& I hope we may still have we often talk

of the nights we past last winter playing

Chicken & we hope we may spend more such

he is a sitting on the flore on the ground

mending his pants write me a letter &

stick it in with Jims

from your affectionate cousin John H Mather

& Co

Jim’s letters continued:

12/13/1862 From Houston, Missouri. "the

mails has just come and brought ... a letter for

John. from Squire and Sterling."

12/28/1862 From Houston, Missouri. "John

Mather and I wrote to Squire and George a few

days ago."

On January 11, 1863, Jim Bethard was one of

twenty-five volunteers from Company B who

participated in the one-day battle at Hartville,

Missouri. In his next letter he explained to Cal

why her brother and cousin didn't participate:

01/22/1863 From Houston, Missouri. “I

believe I forgot to tell you in my last why Jim

and John were not with us in the fight . . . .

they were out on a four day forrage expedition

and had not got back to camp when we started we

met them on the way but they were too near worn

out to turn back."

03/01/1863 From Iron Mountain, Missouri.

"James and John and Frank Farrand and I were

on the highest pinacle of the little mountain

called Pilot knob from whence we could see in all

directions."

03/02/1863 From Iron Mountain, Missouri.

"John Mather is verry well liked by the

majority of the company."

03/21/1863 From Ste. Genevieve, Missouri.

"John Mather received a letter from his

mother yesterday evening."

From Ste. Genevieve, the regiment was transported

down the Mississippi to Milliken’s Bend

where General Grant was organizing a massive

three-corps army to capture the Confederate

stronghold at Vicksburg. To avoid its guns, they

walked and waded south through farms, swamps and

bayous on the west side of the river. On April

30, 1863 they crossed to the Bruinsburg landing

on the east bank. As the point regiment for the

entire army and led by a former slave, they

started inland. About midnight they drew brief

fire from enemy pickets, but both sides then

rested on their arms. The next day, John

participated with his regiment in the day-long

Battle of Port Gibson.

On May 16, 1863 he was present at the Battle of

Champion's Hill although their commanding

general, John McClernand, held them in reserve

throughout the battle and their involvement was

limited to guarding prisoners, gathering arms,

and engaging in some light skirmishing after the

battle.

On May 17th, the 21st and 23d Iowa infantries led

an assault on entrenched Confederates at the Big

Black River Bridge and, again, John participated.

Regimental casualties were seven killed in

action, eighteen mortally wounded, and forty

wounded less severely. Among the most seriously

wounded was Colonel Merrill who fell on the field

with wounds to both thighs.

Jim Bethard had become ill and was left behind

west of the river and was still there when he

wrote his next letter:

05/18/1863 From Ashwood Landing, Louisiana.

"I suppose you received a letter from John

Mather written when I was in the hospital stating

that we had been paid off and that I had sent you

$40 . . . . as I was quite sick Mr Lyons came to

the hospital . . . . so I gave him the money and

he said he would attend to it and get John Mather

to write to you."

Jim caught up with his regiment on the siege line

at the rear of Vicksburg. While Jim had recovered

his health, John had become ill:

06/04/1863 From Vicksburg, Mississippi.

"John Mather is quite sick I believe his

complaint is chronic diehrea he is in the

hospital and I have not seen him since I came

here I intend to go up to the hospital to day to

see him but it is doubtful whether I get to see

him or not when I go for Jim says he has been

several times and could not find him."

06/07/1863 From Vicksburg, Mississippi. "I

was up and seen John Mather the day that I wrote

to you before he was up and around and mending

slowly he looks verry slim but is doing well at

present I have not seen him since that day but I

hear from him every day . . . . Cal I am not at

all surprised that you have not received my dress

coat . . . . John Mather came and got mine but

for some reason they did not go and mine came

back home."

06/15/1863 From Vicksburg, Mississippi.

"John Mather has been on the decline for the

last three days he left the hospital about a week

ago he told me this morning that he was going

back today."

Four days later, on June 19, 1863, John Mather

died from congestive chills and chronic diarrhea.

Some records erroneously report that John died on

June 10th, but it was clear from Jim’s

letter that John was still alive on June 15th.

The Company Muster Roll, an Inventory of

John’s personal effects signed by Captain

William Crooke, a Casualty Sheet, a report from

War Department, and a report from the Surgeon

General's Office all confirm the death was on

June 19th. John was buried in an apple orchard on

the Ferguson farm, about two miles to the rear.

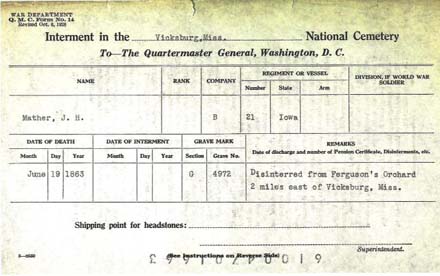

After the war he was reburied in the National

Cemetery at Vicksburg, Section G, Grave 4972.

Reinterment document ...from Ferguson's Orchard

to Vicksburg National cemetery ... courtesy of

Cherie Valentine, a Mather descendant.

Jim wrote again:

06/21/1863 From Vicksburg, Mississippi.

"James Rice has written of John Mathers

death to his [Jim Rice’s] wife and I wrote

to [your] Aunt Philena [John’s mother]

yesterday It will be a great shock for her I feel

sorry for her but it is the fortune of war John

was a good and brave soldier but he now fills a

soldiers grave he has done his duty and gone to

his rest."

On September 26, 1863, John Mather's brother,

Squire, died of chronic diarrhea in Lansing,

Iowa, while at home on furlough. On March 30,

1864, Darius, died of erysipelas at Vicksburg.

Like John, he is buried in the city's National

Cemetery. The names of the three brothers appear

on a memorial marker in Postville Cemetery.

The fourth brother, John Sterling Mather,

survived the war, moved west and died on January

8, 1908. He is buried in Woodland Cemetery,

Woodland, California.

Philena Mather's husband had died in 1861. Three

of her children died in infancy and she had now

lost three of her sons to war. She married

William Bishop in 1863 but, eight months later,

he too died. Philena applied for a widow's

pension from the federal government, but her

application was never acted upon and the date of

her death is unknown.

~*~*~

Maxson, Christian Smith

Records indicate David Maxon was born in Ohio in

1830, Prudence Maxson in Ohio in 1835, and

Christian Maxson in Indiana on October 18, 1842.

All three, siblings, moved to Iowa prior to the

Civil War. David and Christian would serve in

Company B of the 21st Regiment of the Iowa

Volunteer Infantry, as would Prudence's husband,

Seymour Chipman.

The regiment was raised in the state's

northeastern counties, primarily Clayton and

Dubuque. Christian enlisted in Lodomillo Township

on August 6, 1862, the company was mustered into

service on August 18, 1862, and the regiment was

mustered in on September 9, 1862. Christian was

described as being 5' 3¾” tall with blue

eyes, auburn hair and a light complexion. Like

others, he was paid $25.00 of the government's

enlistment bounty (the $75.00 balance being due

on completion of service) and a $2.00 premium.

Most in the company were farmers who, said their

captain, William Crooke, had to learn "the

process of getting used to restraints of freedom,

to inclemencies of weather, to hard beds, and new

forms of food, sometimes not well cooked. ...

habits of obedience had to be formed."

Further advice came from the Wapello

Republican that said: "the Horrors of

War can be greatly mitigated by that sovereign

remedy, Holloway's Ointment, as it will cure any

wound, however desperate, if it be well rubbed

around the wounded parts, and they be kept

thoroughly covered with it. A Pot of ointment

should be in every man's knapsack."

Training was at Camp Franklin, "on a sandy

plateau on the bank of the Mississippi" a

mile or two above Dubuque. Its ten buildings were

each twenty by sixty feet and "arranged to

accommodate one hundred men each." On

September 16th, they left for war.

For the first year Christian maintained his

health well and, on January 11, 1863, he was one

of twenty-five volunteers from Company B who

participated in the daylong Battle of Hartville

in Missouri. Casualties were light, but the

physical strains of hurrying to Hartville and,

after the battle, returning to their base in

Houston, during a harsh winter, were hard on

everyone. Some had to be discharged and many

others would suffer the rest of their lives.

Christian continued with the regiment during the

1863 Vicksburg Campaign during which he

participated in the May 1st Battle of Port

Gibson, was present during the Battle of

Champion's Hill on May 16th when the regiment was

held in reserve during the battle (although he

may have been one of he few men allowed to engage

in post-battle skirmishing), participated in the

May 17th assault at the Big Black River, and

participated in the May 22nd assault at

Vicksburg. After the surrender of the city, he

participated in the expedition to and siege of

the capital at Jackson.

By then, however, his health had declined and he

was "sent to Hospl at Keokuk Iowa July 14,

1863." Muster rolls for the Keokuk U.S. Army

General Hospital indicate he was admitted as a

patient in late August and, except for an

intervening 20-day furlough, remained in the

hospital until May 13, 1864 when he was released

and transferred back to the regiment.

During his absence, the regiment had served seven

months on the Gulf Coast of Texas. Ordered to

Louisiana, the right wing arrived on June 14th

and the left wing on June 18th and there they

were joined by Christian Maxson. Christian

remained with the regiment as it was stationed at

the Terrebonne Station west of the river,

Algiers, Morganza Bend, at various locations

along the White River in Arkansas, Memphis, and

then for a month in Kennerville, Louisiana.

On August 5th, when Iowa’s 21st Infantry was

at Morganza Bend, Admiral Farragut had a

memorable battle at the entrance to Mobile Bay

and federal infantry occupied forts guarding the

entrance to the bay, but the city of Mobile was

still in the hands of the Confederacy. On

February 5, 1865, the regiment boarded the George

Peabody at New Orleans. Two days later they

went ashore on Dauphin Island where they camped

near Fort Gaines. On March 17th, they crossed the

bay’s entrance to Mobile Point and then

participated in a movement north along the east

side of the bay. The enemy abandoned the city

before the regiment’s arrival on April 12th.

After occupying the city, they camped in nearby

Spring Hill and visited the Jesuit College of St.

Joseph founded thirty-three years earlier by

Michale Portier, first Bishop of Mobile.

On May 26th, said Strawberry Point’s Myron

Knight, "we received orders right after

reveille to pack up and get ready to move."

Leaving Spring Hill about 6:00 a.m., they reached

Mobile four hours later. They then spent most of

the day resting in the shade until 5:00 p.m. when

they boarded the river steamer Mustang

and started a return to New Orleans. On arrival

Christian Maxson was admitted to the Marine

U.S.A. General Hospital. Still there with the war

coming to an end, there was no need for him to

remain in the military and he was discharged on

June 4, 1865. His regiment would be discharged

the following month at Baton Rouge.

Christian was married three times. He married

Clarrissa (also shown as Clarissa) Fisher on

October 27, 1865. She died on November 4, 1872,

and was buried in Gantz Cemetery in Abingdon,

Iowa. He then married Lorana (Bush) Newman on

October 13, 1877. She died on December 28, 1887,

and was buried in Edgewood Cemetery. His final

marriage was to Effie (also shown as Effa) May

Robbins on September 1, 1888.

Effie was almost twenty-eight years younger than

Christian and four years younger than Mary, one

of his daughters. Effie joined the Woman's Relief

Corps, an allied order of the Grand Army of the

Republic, and helped organize the Hiram Steele

Relief Corps of the WRC. The following year she

was an organizer and officer of Purity Temple No.

4, a local chapter of the Pythian Sisters, a

female auxiliary of the Knights of Pythias. Effie

and Christian would have two children, Mary

Matilda and Irma V. Maxson.

Christian worked as a merchant in Edgewood, Iowa,

where, on December 26, 1928, he died. Effie died

on November 22, 1947. They're buried in Edgewood

Cemetery

~*~*~

Maxson,

David John

Ephraim and Mary (Smith) Maxson reportedly had

ten children. Among them were Sarah born February

8, 1824, in Ohio, David born in Ohio in 1830, and

Prudence who was born January 12, 1835, in Ohio

or Michigan. For numerous reasons, Ohio seems

much more likely. From Ohio, the family moved to

Indiana where Christian was born on October 18,

1842. They then moved to Michigan and in 1852 to

Iowa. Sarah was married to Andrew Marshall and,

on August 24, 1853, in Strawberry Point, Prudence

married Seymour Chipman.

On December 24, 1856, David and Harriet Ann

Stevens were “duly joined in marriage by

Andrew Marshall a Justice of the Peace” in

Elkader (possibly the same Andrew Marshall who

was married to Sarah). A daughter, Jane Ellen

“Ellie” Maxson, was born in Elkader on

September 22, 1857.

On April 12, 1861, Southern guns fired on Fort

Sumter. President Lincoln called on the

“militia of the several states of the Union

to the aggregate number of 75,000 in order to

suppress said combinations and to cause the laws

to be duly executed." The War Department

asked Northern states to provide infantry or

riflemen for a maximum of three months "to

suppress insurrection.” Three months seemed

plenty of time, but "the gravity of the

revolt" and the "power and will of the

Slave States" were, said Walt Whitman,

"not at all realized at the North, except by

a few."

As the war progressed into a second year, more

volunteers were needed. On July 9, 1862, Iowa

Governor Kirkwood was asked to raise five

regiments and, despite the imminent fall harvest,

the state responded. David Maxson enlisted on

August 5th, Christian on the 6th and their

brother-in-law, Seymour Chipman, on the 11th. On

August 18th, they were among ninety-nine men

mustered in as Company B with David Maxson as 7th

Corporal. On September 9th, at Camp Franklin in

Dubuque, ten companies were mustered in as the

21st regiment of Iowa’s volunteer infantry

with McGregor banker Samuel Merrill as Colonel.

On September 16, 1862, they left for war on board

the Henry Clay and two barges lashed to

its side. The first seven months of their service

were spent in Missouri. After spending one night

in St. Louis, they traveled by rail to Rolla and,

from there, marched to Salem, Houston, Hartville,

back to Houston, south to West Plains, and then

northeast to Thomasville, Iron Mountain, Ironton

and finally, on March 11th, into the old French

town of Ste. Genevieve.

By then regimental strength had dropped from 985

at muster to only 882. Due to the vacancies that

had been created in some of the officer ranks,

David Maxson received incremental promotions to

6th Corporal, 5th Corporal, 4th Corporal and 3rd

Corporal. On March 19th, still at Ste. Genevieve,

David and several others were granted furloughs.

While they were gone more vacancies occurred and,

effective April 1, 1863, David was promoted to

1st Corporal.

David was still on furlough when the regiment was

taken down-river to Milliken’s Bend where

General Grant was organizing a massive army for

the purpose of capturing the Confederate

stronghold at Vicksburg. On a rainy April 12th,

they moved to Richmond, Louisiana, where they

were detailed to improve roads and work on a

levee and that’s where they were on April

14th when Company B’s Myron Knight wrote in

his diary: “did not feel very well - was

detailed to watch guns while the rest were to

work on the road - finished the work about noon

and came back to camp. Saw Wm. Lebert - belongs

to the battery. Three of the furloughed men came

back W. W. Lyons, D. Maxson and John

Carpenter.”

From Richmond they continued south over roads,

across bayous and through swamps on the west side

of the Mississippi River until camping on the

Disharoon plantation. On April 30th, they crossed

to the east bank and the 21st Iowa Infantry had

the honor of being the point regiment at the

front of the Union army as it started a slow

movement inland. About midnight, near the Abram

Shaifer house, shots were fired by Confederate

pickets. Union soldiers responded but, unable to

see each other in the darkness, both sides soon

rested. On May 1, 1863, David participated with

his regiment in what the North called the Battle

of Port Gibson. On the 16th they were present,

but held in reserve during the Battle of

Champion’s Hill, although Companies A and B

were allowed, late in the day, to help guard

prisoners and gather abandoned weapons.

On the 17th, they were in the lead with a

four-regiment brigade led by Michael Lawler. As

they approached the railroad bridge over the Big

Black River, they encountered entrenched

Confederates who were hoping to keep the bridge

open long enough for troops they thought were

still withdrawing from Champion’s Hill to

cross the river. Union officers conferred, an

assault was ordered and, in three minutes, it was

over. The Confederates had been routed, but

regimental casualties were heavy. Seven men were

dead, eighteen had wounds that would prove fatal,

and at least forty suffered less serious wounds.

Among them was David Maxson who, a report said,

was “wounded in side ball lodging near the

spine between the shoulder.”

Grant’s army continued to the rear of

Vicksburg, but regiments that participated in the

assault remained behind to bury their dead and

treat the wounded. Eventually, when safe access

was gained to the Mississippi River, many were

moved elsewhere so they could get better

treatment. Colonel Merrill, who had given the

order to charge, was seriously wounded while

leading the assault and was one of many taken to

Iowa. Others were sent to hospitals in St. Louis

and Memphis while David, on August 11th, was

taken on board the Charles McDougall

hospital boat where he was treated for his wound

and for “febris intermittens,” a term

most often applied to malaria. David’s

treatment continued as he was transported

upstream and, on August 18th, he was admitted to

the general hospital at St. Louis’ Benton

Barracks. In the meantime, effective July 3,

1863, David was promoted to 5th Sergeant.

On October 12, 1863, he rejoined his regiment,

then stationed at Vermilion Bayou in Louisiana

and he remained present through the end of the

year. Earlier that year the War Department had

created an Invalid Corps for men unable to

perform regular field duty, but still capable of

light work (e.g. serving as hospital nurses,

guarding prisoners, cooking and working as

orderlies). The 20th Regiment of the corps was

organized on January 12, 1864. The following

month David was found unfit for field service but

still able to perform light duties and, on

February 29th, he was transferred to the 20th

Regiment then stationed in Maryland.

His sister, Sarah, died on March 15, 1864, and

was buried in Noble Cemetery, Yankee Settlement

(Edgewood), while David continued his service in

Maryland. The name of the corps was changed to

Veteran Reserve Corps and David was still with it

when, on July 25, 1864, he died from malaria

(also shown as “congestive intermittent

fever”) at Point Lookout, site of the

largest Union prison camp for Confederates. A

military stone, with an adjacent GAR marker*, in

Noble Cemetery indicates his body was sent home

for burial.

Harriet was twenty-seven years old when her

husband died and, on August 10th, she signed an

application for a widow’s pension with

support from Elkader judge Alvah Rogers who

attested to her marriage to David. The Adjutant

General’s Office verified David’s

service and, on February 24, 1865, Harriet was

awarded an $8.00 monthly pension retroactive to

David’s death.

Harriet also requested a pension for her

daughter. Margaret Hughes and Jane Stevens signed

a joint affidavit saying “we were present at

the time Jane Ellen Maxson was born,” she

was the only child of the marriage, and she was

born on “the 22nd day of September A.D.

1857.” On April 1, 1867, a certificate was

issued authorizing an additional $2.00 monthly

that would continue until Jane’s sixteenth

birthday.

On September 9, 1869, at Delhi, Harriet married

John N. Steele. In November she signed an

affidavit notifying the Pension Office of her

marriage and surrendering her certificate, but

said she had been appointed Guardian for her

now-twelve-year-old daughter. A monthly pension

of $8.00 was granted and a certificate was issued

March 28, 1870. The certificate was later lost,

but a new claim was approved and, on January 10,

1874, a new certificate was issued. By then Jane

was sixteen, but accrued amounts would still be

paid

Sarah and David had died in 1864. In 1927

Prudence died in Corvallis, Oregon, and in 1928

Christian died in Edgewood.

_____ _____

*note from Clayton co. coordinator - many

times a GAR marker is placed next to a CW

veteran's gravestone to denote that they did

serve during the CW. Not all CW soldiers were

members of the GAR, which was started after

the War...sgf

~*~*~

McCafferty, Hugh H.

Hugh McCafferty was born in Philadelphia but the

year of his birth is uncertain. In military

documents his age was listed as 18 when he

enlisted (indicating a birth year of 1843 or

1844), but in postwar pension documents the age

he listed indicated a birth year of 1847 or 1848

possibly indicating he may have been underage and

made a “patriotic fib” when he

enlisted.

On August 12, 1862, Hugh and several others were

enrolled at Elkader, Iowa, by Elisha Boardman in

what would be Company D of the 21st Iowa

volunteer infantry. The company was mustered in

on August 22nd and the regiment on September 9th,

both at Camp Franklin on Eagle Point in Dubuque

although Hugh “was absent when the company

was mustered in” and, as a result, did not

receive the $25.00 advance on the enlistment

bounty, nor the $2.00 premium, nor the $13.00

advance monthly salary until much later.

On September 16th, from the levee at the foot of

Jones Street, they boarded the sidewheel

four-year-old steamer Henry Clay (an “old

tub” according to some) and two barges tied

alongside and left for war. Their early service

was in Missouri where, on October 20th at Salem,

Hugh was detailed as a teamster. Two months later

they were in Houston where Hugh was fined $13.00

for unspecified “misconduct.” Some

members of the regiment engaged in a battle at

Hartville in January before the regiment moved

south to West Plains and then northeast through

Thomasville, Ironton and Iron Mountain before

reaching Ste. Genevieve on March 11, 1863. From

there, in April, they were transported south to

Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, where General

Grant was assembling a large three-corps army at

the start of his successful Vicksburg campaign.

Serving under General John McClernand, the

regiment started south along the west side of the

river on April 12th, the same day Hugh was

detached and detailed to the 1st Iowa Battery of

light artillery. The following month he was

detailed to Battery A of the 2nd Illinois light

artillery (also known as the Peoria Battery) and

from there he was ordered back to his own

regiment but due to illness was admitted to the

division hospital. The siege of Vicksburg ended

with the city’s surrender on July 4th and

the regiment then participated in an expedition

to and siege of Jackson before returning to

Vicksburg and then being transported south to

Carrollton, Louisiana, where it arrived on August

15th - but Hugh was still in Mississippi.

On August 19, 1863, he was arrested near Redbone

Church and, on the 20th, the colonel of the 2nd

Wisconsin Cavalry wrote to an assistant adjutant

general that, “I forward to you under guard

Private H. McCaverty 21st Iowa Vol Infty who has

been going around the country at the head of a

band of armed Negroes. I also send one of the

band Daniel White (colored). They were taken by

one of my scouting parties last evening”.

The Provost Marshal in Vicksburg then wrote to

General McPherson that “the Prisoner

McCafferty states that you sent him out as a

Guard at a House beyond the lines, and that when

taken he was in pursuit of a party of Rebels that

had seized two Govt. wagons.” McPherson

disagreed saying, “I am inclined to think

that this Private McCafferty is a bad man. I

never sent him out as guard, but briefly gave him

a pass to return to the house at which he had

been staying.” Hugh was ordered to report to

his commanding officer since the regiment was

about to move but “this he seems not to have

done and he deserves some punishment.”

Unlike Hugh’s earlier problem when he was

fined $13.00, military records have no record of

him being punished after returning to his

regiment and later that month he was detailed as

a teamster and ordered to report to a U.S.

Constable at Carrollton.

While there he became sick and was sent to a

convalescent camp on November 5th so he could

regain his health while his regiment saw service

in southwestern Louisiana. He was still there on

November 23rd when his regiment boarded

transports and left for the gulf coast of Texas.

By then, the three-year commitments for men who

had enlisted early in the war were nearing an end

and, hoping to maintain the strength of the army,

the War Department offered a $400 bounty and a

thirty-day furlough to men willing to reenlist.

The inducement proved to be a strong lure not

only for men nearing the end of their commitments

but also for Hugh McCafferty. On his release from

the convalescent camp in January, 1864, he and

fifteen of his comrades enlisted in the 1st

Indiana artillery as veteran volunteers where

they were examined by a surgeon and mustered into

the regiment. When it was discovered that they

were still on the rolls of the 21st Infantry and

their terms had not expired, they were ordered

returned to their regiment. As Gilbert Cooley

noted, “Hugh McCaffery returned to the

regiment and was put under arrest and charges

preferred” for having enlisted in the 1st

Indiana. A court martial was convened and, on

July 9th, Hugh was found guilty of having

enlisted in the Indiana artillery without being

discharged from his own regiment and for

disobeying an order to report to his regiment

after being discharged from the convalescent

camp. He was sentenced to lose five months’

pay but Elisha Boardman wrote on Hugh’s

behalf that he “was no more guilty of

improper conduct than the rest of these men”

and he should not be penalized. The commanding

general agreed, Hugh’s sentence was remitted

and he was returned to the regiment without

penalty.

Hugh was present on the August 31st muster roll

at Morganza, Louisiana but, on September 9th from

the mouth of the White River, he was sent to

Memphis where he was admitted to the Overton

General Hospital for anemia. Three days later he

was released and rejoined the regiment which had

also moved to Memphis. In December, Hugh was

again sick and, according to Cooley, Hugh

“was left Sick in Camp on Dec. 21st 1864

while the Regiment went on what was known as

Grierson Raid from Memphis from which the Regt

returned Dec 27th.” On the 31st, Cooley

wrote again and again said Hugh was sick.

On January 5, 1865, the regiment arrived in New

Orleans and made camp in Kennerville. To men

aware they would soon be leaving on an expedition

to Alabama, the “good times” of New

Orleans proved to be a strong attraction, an

attraction too strong for Hugh who visited the

city without leave on January 21st and did not

rejoin his regiment until ten days later.

On February 5th they boarded the George Peabody

and, on the 6th, left for Alabama where they

arrived on the 7th and bivouacked near Fort

Gaines on Dauphin Island. A court martial was

convened the next day and Hugh admitted his

guilt. He had earlier been fined one month’s

pay for “misconduct,” he had been

arrested but suffered no penalty after leading

the band of armed Negroes in Mississippi and his

sentence for improperly joining the 1st Indiana

Artillery had been remitted, but this time he was

not so lucky and was sentenced “to be

confined in some Government fort to be designated

by proper authority for the period of Twenty days

with a ball and chain attached to left leg.”

He was imprisoned in Fort Morgan on Mobile Point

until returning to duty on March 8th.

He then participated in the campaign to occupy

the city of Mobile, served as a teamster at

Spring Hill, Alabama, and was with the regiment

on July 15, 1865, when it was mustered out at

Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They started north the

next morning and were discharged from the

military at Clinton on July 24th.

With the war over, Hugh married Elizabeth James

and they had one child, John A. McCafferty, on

September 8, 1877. Two years later, in October of

1879, while living in Missouri, he had an

accident going from Omaha, Nebraska, to Ozark,

Missouri, and my “team run away with me and

broke my hip.” His leg was fractured, the

fibula was dislocated and his injuries

didn’t heal well resulting in his right leg

being an inch and a half shorter than his left. A

few years later, in Vernon County, Elizabeth

died.

On March 23, 1884, Hugh married

twenty-seven-year-old Rhoda F. Coose in the town

of Everton. They had two children - Alice Delilah

on July 9, 1885, and Rosa “Rose” A. on

January 20, 1893.

Like many Union veterans, Hugh applied for a

postwar invalid pension. He first applied on

March 31, 1887, when the law required a

war-related illness or injury. Hugh said he was

thirty-nine years old and during the siege of

Vicksburg had “contracted piles caused by

exposure and hard marching from the effects of

which he has never recovered.” Government

records confirmed his treatment at the Overton

General Hospital but showed no other medical

problems. In September, a board of pension

surgeons in Springfield, after confirming the

seriousness of his hemorrhoids, recommended a

6/8th pension rating and numerous friends

submitted affidavits on his behalf but no pension

was granted.

He applied again in 1890 after a new act required

a disability that hindered the applicant’s

ability to do manual labor but did not require

that the disability be war-related. This time he

referred not only to the piles, but also to his

leg injury. A board of surgeons confirmed both

conditions and again recommended a pension be

granted but the application lingered until 1902

when the Commissioner raised questions about his

age at enlistment. By then Hugh was living in

Tecumseh, Oklahoma. On July 13, 1906, nineteen

years after he first applied, Hugh was approved

for $12.00 monthly pension. He died on July 28,

1908, and is buried in Tecumseh Cemetery.

Three days after his death, Rhoda, now fifty-one,

applied for a widow’s pension. She was

approved at $12.00 monthly with another $2.00 for

Rosa until her sixteenth birthday. As new laws

were enacted, Rhoda’s pension was gradually

increased to the $40.00 she was receiving when

she died on December 15, 1943. Rhoda, like Hugh,

is buried in Tecumseh Cemetery.

~*~*~

McGrady, James

Born on July 12, 1827, in Grand Isle County,

Vermont, James McGrady was one of two sons born

to Irish immigrants James and Laura

“Lucy” (White) McGrady. On August 31,

1854, in Clayton County, Iowa, James and Laura L.

Wallace were married. They would have ten

children, three before James’ military

service and seven after.

On April 1, 1861, Confederate General Beauregard

demanded the surrender of Fort Sumter and at 4:30

a. m. the next morning he opened fire. Union

troops under Major Robert Anderson evacuated the

fort on the 14th and on the 15th, with a regular

army of only 16,000, President Lincoln called for

volunteers. The war that followed quickly

escalated, thousands died and on July 9, 1862,

Iowa Governor Kirkwood received a telegram asking

him to raise five regiments as part of the

President’s call for 300,000 three-year men.

On August 11, 1862, at Farmersburg, James McGrady

enlisted in what would be Company E of the 27th

regiment of Iowa’s volunteer infantry. When

mustered in on October 3rd he was described as

being a 5' 7½” farmer with

“grayish” eyes, light brown hair and a

dark complexion. On the 11th the regiment was

ordered to report to Major General John Pope in

Minnesota where four branches of the Santee Sioux

(the Dakota) had led an uprising. The regiment

camped near Fort Snelling and a few days later

six of the ten companies were ordered to Mille

Lacs. When their services were no longer needed

in Minnesota they started south and all ten

companies were united at Cairo, Illinois. From

there they were transported to Memphis where they

joined an army led by William Sherman to

reinforce Ulysses Grant. They then performed

guard duty on the Mississippi Central Railroad

until late in the year.

Unknown to the federal army, Confederate General

Earl Van Dorn left Grenada, Mississippi, with

3,500 men on December 17th. On the 18th he was

sighted by Union cavalry but it was more than

twenty-four hours before Grant was alerted to the

threat. Late on the 19th he sent a warning to

Colonel Murphy at the Union supply depot in Holly

Springs. Early the next morning Van Dorn attacked

the depot and captured 1,500 prisoners and tons

of medical, quartermaster, ordnance and

commissary supplies before heading away to the

north.

Meanwhile Union forces to the south had been put

on the alert and James’ regiment was

guarding a rail line over the Tallahatchie River.

James later explained that, under instructions

from 1st Sergeant Garner Williams, they rushed to

try to find one of James’ comrades who been

serving as a sentinel but was thought to be

missing (“gobbled up” according to

Jonathan Smith). While hastily crossing a

railroad trestle, James slipped, fell and landed

hard straddling a railroad tie and severely

injuring his back and testicles. On December 31st

the regiment was taken by rail to Jackson,

Tennessee, where James was treated in a field

hospital. When the regiment was ordered to

Corinth on April 20, 1863, James remained at Camp

Read in Jackson until rejoining the regiment on

May 30th.

In June they went by rail to Grand Junction and

then La Grange, Tennessee, and from there they

walked to Moscow where they guarded the line of

the Mississippi Central Railroad. In August they

moved to Memphis before being transported to

Helena, Arkansas. James remained present as they

saw service along the White River, but on January

2, 1864, was granted a furlough “for 30 days

on account of sickness in his family and his own

disability.” He was transported to Cairo and

from there went to Prairie du Chien before being

admitted to a general hospital in Davenport where

an August 15, 1864, Certificate of Disability for

Discharge said James was “incapable of

performing the duties of a soldier because of

Chronic Diarrhoea of one years duration chronic

Bronchitis Emaciation & general

debility.” On October 4th he was discharged

from the military with mail to be forwarded to

him in Farmersburg. About eight years later, he

moved to Clear Lake, Iowa.

Pension laws then in effect for Northern soldiers

required at least ninety days’ service, an

honorable discharge and a service-related

disability. If granted, pension amounts were

based on the degree to which the veteran was

disabled from performing manual labor. When James

signed an application on June 29, 1879, he based

his claim on the fall he had taken from the

railroad trestle and said “he is now fully

2/3rd disabled from obtaining his subsistence by

manual labor.” A supportive affidavit from

Jonathan Smith said James was bedridden for six

months after he “fell straddle of a tie on

said Tresle work & Bruised the

Testicles.” When files of the Adjutant

General’s Office and Surgeon General’s

Office were searched, there was no record of

either the injury or the hospitalization.

Another Company E comrade, Samuel Benjamin,

signed an affidavit on October 16, 1880, and

agreed that “as he fell he struck the saddle

of a stick of timber striking on his testicles

and injuring the small of his back or spine and

rendering him insensible for a time” and

“was operated on in the field hospital by

having his back lanced.” Two days later, in

Clear Lake, James was examined by Dr. McDowell

who signed a certificate saying James had pain

and tenderness on the left side of the spine and

“he has trouble of the scrotum and testicles

every month he has a crop of vesicular or

eczematous eruption come out on the scrotum . . .

and about half of the time he is unable to walk

about on account of the inflammation of the

parts.” In the doctor’s opinion, James

was entitled to a pension of “1/2 total for

spinal irritation 1/2 Total for chronic

eczema.” On March 4, 1882, the regimental

surgeon, Dr. John Sanborn, said he had an

“indistinct recollection” of treating

James “at or about the time of the rebel

raid on Holly Springs, Miss. for an injury to

spine and testicles, and that he was probably

disabled for some months.” More affidavits

from James, Samuel Benjamin and Jonathan Smith

followed and on February 7, 1883, Dr. McDowell,

who had known James for twelve years, conducted

another medical exam, this time saying James

could no longer control his bladder, had a

“constant desire to make water” and

“it is my opinion that he will not live very

long.” In March, almost four years after the

claim was submitted, it was rejected by medical

officers in the pension office for “failing

to satisfactorily show the origin of the alleged

disability in the service & line of

duty.”

James continued to pursue his claim. Samuel

Benjamin signed three more affidavits, Jonathan

Smith signed two, Dr. McDowell conducted another

examination, a neighbor who saw James

“nearly every day” said James was

“troubled with his Back & his urinary

organs” and Henry Holm (husband of

James’ daughter, Cynthia) said James

“could not make an average more than 1/4 of

a hand he never did any work at all that required

any great muscular exertion,” “his Back

would give out” and “his testicles were

Badly desordered” and sometimes greatly

swollen. Arza Taylor signed an affidavit saying

he and James “were bunkmates at the time he

got hurt . . . by falling straddle of a tie while

patroling the railroad about 5 days before we

went up to Jackson Ten.” Dr. McDowell wrote

on August 28, 1886, that James was confined to

his bed, “nothing but a skeleton” and

“liable to die any day.” On September

15th, Dr. McDowell and Dr. Irish examined James

in Mason City and said there were scars on each

side of the spine “as if they had been done

by a lance” (as Samuel Benjamin had

testified six years earlier). On October 18th,

James was again examined by Dr. McDowell who said

there were four or more scars on each side of the

spine and James had “the appearance that he

would not live six weeks.”

Finally, more than seven years after James

applied, his claim was approved and on November

23, 1886, a certificate was mailed that reflected

a monthly pension of $4.00 from the day after his

discharge and an increase to $8.00 from the date

of Dr. McDowell’s 1883 medical examination.

When it was realized that the 1886 examination

had not been taken into consideration, the amount

was increased to $24.00 from the date of the

examination and a new certificate was mailed on

June 1, 1887. On August 7, 1887, James died. He

was buried in Clear Lake Cemetery.

On August 26th Laura signed an application

seeking that portion of the pension that had

accrued but not yet been paid when her husband

died and on November 2nd she signed an

application requesting a widow’s pension and

a pension for their three children who were still

under sixteen. Her applications were approved on

April 18, 1888, at $12.00 monthly for her and

$2.00 monthly for each of the children. Laura

died on July 5, 1904, and, like James, is buried

in Clear Lake Cemetery.

~*~*~

McIntyre, Peter

Peter Mcintyre (also spelled "Mclntier"

and "McAntier" in military records) was

born in Ireland. His age was listed as

twenty-four when he was enrolled at McGregor for

three years by Willard Benton on August 15, 1862.

Peter was described as being a 5 feet 9½ inch

farmer with hazel eyes, black hair and a dark

complexion. On August 22nd, they were mustered in

as Company G and, on September 9th, they were

mustered into service as the state's 21st

Infantry with each volunteer paid $25.00 of the

$100.00 enlistment bounty and a $2.00 premium.

After brief training of minimal value at Camp

Franklin in Dubuque, they walked through town on

a rainy September 16, 1862, crowded on board the

paddlewheel steamer Henry Clay and two

barges tied to its side, and started south. After

an overnight stay at Benton Barracks in St.

Louis, they boarded railroad cars and traveled

through the night to Rolla.

For many months they saw service in southern

Missouri - Rolla, Salem, Houston, Hartville, West

Plains, Ironton, Ste. Genevieve - before going to

Milliken's Bend, Louisiana, where they became

part of a massive army being organized by General

Grant to occupy the Confederate stronghold at

Vicksburg.

Each Company was led by a Captain, 1st

Lieutenant, 2nd Lieutenant, five ranks of

Sergeant and eight ranks of Corporal. Records for

Peter are somewhat conflicting with one saying,

on February 24, 1863, he was promoted from

Private to 7th Corporal and another saying it was

to 5th Corporal. Subsequent promotions were to

4th Corporal on May 31, 1863, 3rd Corporal on

September 18, 1863, 2nd Corporal on April 1,

1864, and 1st Corporal on August 1, 1864.

Company muster rolls were prepared on a bimonthly

basis and reflected the presence or absence of

the soldier as of the last day of the period.

Peter was marked ''present" on every roll

until being mustered out with the rest of the

regiment at Baton Rouge on July 15, 1865.

On April 5, 1864, Colonel Merrill signed an order

providing that "Corporal P. Macintire Co G

is hereby detailed a corporal of the color guard

and will report forthwith for duty,"

although it's not clear how long he served in

that capacity.

During his service he participated in the Battle

of Port Gibson, Mississippi, on May 1, 1863, was

present while the regiment was held in reserve

during the Battle of Champion's Hill on May 16,

1863, and participated in the assaults at the Big

Black River Bridge on May 17, 1863 and at

Vicksburg on May 22, 1863. He was present for the

duration of the siege of Vicksburg, accompanied

the regiment during a pursuit of Confederate

General Joe Johnston to Jackson, Mississippi, and

was with the regiment during its service in

Texas, and the campaign that resulted in the

occupation of Mobile, Alabama, on April 12, 1865.

With the war at an end, the government had no

need for the hundreds of thousands of muskets,

other arms and accouterments then in the hands of

the military. The War Department's General Order

No. 101 permitted men to keep their muskets and

accouterments for $6.00, money a cash-strapped

government could use. Like many others in the

regiment, Peter elected to keep his musket and

accouterments when they were mustered out on July

15, 1865 at Baton Rouge. From there they went

north by river transport as far as Cairo where

they debarked and traveled the rest of the way by

rail. On July 24, 1865 they were discharged from

the military at Clinton.

~*~*~

McKinnie, Linus P. 'Line'

Linus P. McKinnie was born in Ohio and was a

thirty-one year old Clayton County farmer when,

on August 14, 1862, he was enrolled at McGregor

by postmaster Willard Benton for three years

"or the war." While soldiers in current

wars have "dog tags" for

identification, soldiers in the Civil War had a

hand-written Company Descriptive Book that gave

the soldier's physical description and other

information from his Muster-in Roll that was then

augmented during his service. Linus was described

as being 5' 7¼'' tall with dark eyes, brown hair

and a dark complexion.

Each infantry company had eight ranks of Corporal

and Linus started his military career as a 6th

Corporal in Company G that was mustered in on

August 22, 1862. When all ten companies were of

acceptable strength, they were mustered in at

Dubuque’s Camp Franklin on September 9th as

the 21st Regiment of Iowa's Volunteer Infantry.

They started south on September 16th on board the

sidewheel steamer Henry Clay and two

attached barges and, the next month, possibly due

to his age and a better than average education,

Linus was given the responsibility of Company

Clerk. The following month he was detailed as an

Orderly for Colonel Merrill, but on December

12th, Merrill ordered that Linus be "reduced

to the ranks at his own request and this to take

effect from Dec. 1, 1862. Maple Moody appointed

in his stead."

The first several months involved a lot of

walking, but was relatively uneventful except for

the evening of November 24, 1862 when a wagon

train carrying supplies from the railhead in

Rolla, Missouri, to the regiment then stationed

in Hartville was attacked and three men were

killed. This brought a hard dose of reality to

their mission and it was a shock for many when

they viewed the bodies of their dead comrades. On

January 11, 1863, Linus was one of 25 volunteers

from Company G (262 men from the regiment) who

participated in the daylong Battle of Hartville

resulting in three killed in action, one fatally

wounded, and thirteen non-fatally wounded.

The regiment concluded its service in Missouri by

walking from Houston to West Plains, Thomasville,

Ironton, Iron Mountain and Ste. Genevieve. From

there they were transported downstream to

Milliken’s Bend where General Grant was

organizing a large army to capture Vicksburg.

Assigned to a corps led by John McClernand, they

walked and waded south along the west side of the

Mississippi until April 30, 1863 when they

crossed to the Bruinsburg landing on the east

bank.

Linus, nicknamed “Line,” was again

serving as Orderly for Colonel Merrill, and then

for Lieutenant Colonel Dunlap, as they started

inland. On May 16th Linus was present during a

battle at Champion’s Hill when the regiment

was held in reserve, but the following day

participated in an assault over open ground at

Confederates entrenched along the Big Black

River. After taking their place on the line

around the rear of Vicksburg, they participated

in an assault on May 22nd and in the ensuing

siege.

During the balance of 1863, Linus served as a

guard, a company cook and a clerk, and word of

his clerical skills apparently spread. On

February 29, 1864, he was detailed for two weeks'

duty as a clerk at brigade headquarters. On March

24, 1864 the regiment was on Matagorda Island in

Texas when Linus was granted a 60-day furlough,

the unusual length possibly due to the long

distance he would have to travel. Leaving the

same day, he reached home three weeks later. Due

back on May 24th, he was still in Iowa when, on

June 6th, Samuel Murdock, a McGregor judge, wrote

to Adjutant General Nathaniel Baker: "to

introduce to your favourable notice Mr Linus

McKinnie of our County. Mr McKinnie has

faithfully served in the 21st Iowa and is now on

his way to his Regiment. From his experience and

expertness and ability you would find him a

valuable help in organizing the New Regiments and

if you have a place for him you will confer on

him and his friends here a great favor by

assisting him to it."

By then, due to wounds received at the Big Black,

Colonel Merrill had resigned and returned to

civilian life as President of McGregor's First

National Bank. On June 7th he signed a letter to

a friend and explained that "L. McKinney the

bearer is a soldier & has been a good &

faithful soldier & was promised as was

supposed a 2d Lieut. in 5th Cav. but for some

reason it don't come." A second letter was

addressed to Adjutant General N. B. Baker

explaining: "the bearer L. McKinney of the

21st Iowa has remained here for 6 or 8 days

expecting a commission of 2d Lieut in the 5th

Cavalry. Maj. Call said Gov. Stone told him he

would coms. McKinney on my recommendation. I gave

my recommendation. McK. is entitled to a

promotion. He has been a good soldier for two

years nearly. If you can put him on the track I

wish you would do so & oblige me. "

Knowing Linus would be late rejoining the

regiment, Colonel Merrill gave him a letter

explaining he had ordered Linus "to remain a

few days for the commission. For some reason

through the absence of the Governor the

commission has not arrived and I have recommended

him to wait no longer but to proceed to his

regiment by way of Davenport. I would say that

his overstay of five days on his furlough is not

his fault." On Linus' return an inquiry was

held, Linus presented Colonel Merrill's letter

and theorized that Merrill had merely been in

error about the number of days Linus would be

late. He was restored to duty without penalty.

On June 26, 1864, they were at Terrebonne Station

(now Schriever) when Linus was again detailed for

work as a clerk, this time for 1st Lieutenant

George Mayers, then serving as an Assistant

Adjutant General. On July 7th, he was relieved as

clerk but, on the 17th, he was again assigned,

this time as Clerk at the headquarters of General

George McGinnis. This proved to be an interesting

assignment.

Washington had finally decided it was time to pay

attention to the city of Mobile and Mobile Bay,

the underbelly of the southeastern Confederacy. A

two-pronged approach would involve both navy and

army. Linus was with the infantry on July 29,

1864, when they left Algiers on the St.

Charles. On the 30th they were underway

pursuant to sealed orders. On August 3rd, Gordon

Granger wired that the St. Charles and

four other transports were anchored off Petite

Bois Island with about 1,700 men and that

afternoon he would start to disembark troops

about ten miles east of the western extremity of

Dauphin Island. Linus wrote that steamers ran

“as close to shore as possible.” Some

men jumped overboard and waded ashore while

others took small boats. By daylight on the 4th

the “heavy siege pieces” were on shore.

On the morning of the 5th, “a day ever to be

remembered,” said Linus: “could be seen

steaming up the bay Farragut and his fleet . . .

the grandeur of which will fill many pages of our

future history, and in less than twenty minutes

from the time of their opening fire the deafening

roar of cannon, with the bursting of shell,

outbattled anything of the present war, and I

doubt if history can produce the equal. The fight

with the rebel ram Tennessee was a thing of no

mean proportions”

Linus, due to his detachment from his own

regiment, had been able to witness the Battle of

Mobile Bay that did, indeed, “fill many

pages” of our history. Fort Powell was

occupied on the 6th and Fort Gaines on the 8th

and, said Linus, “the old Starry Banner was

flying from the ramparts as in days gone

by.”

On the 10th, General McGinnis was ordered to New

Orleans to resume command of his old Division.

Linus went with him and, on August 30th, rejoined

his regiment. The following day, when Judson

Hamilton was reduced to the ranks at his request,

Linus was appointed Quartermaster Sergeant, a

position he held until February 4, 1865, when he

too was reduced to the ranks at his own request.

On the 10th another order was issued, this time

detailing Linus as a clerk at headquarters of the

1st Brigade of a Reserve Corps.

That spring his regiment sailed from New Orleans

as Linus had done many months earlier. They went

ashore at Dauphin Island and camped near Fort

Gaines whose occupation Linus had witnessed the

previous fall. The bimonthly Company Muster Rolls

say Private McKinnie was present with Company G

on February 28th at Dauphin Island, April 30th at

Spring Hill, and June 30 at Baton Rouge (although

there’s a conflicting note that he was

detached in February and not returned until June

5th). On June 23, 1865 he was with the regiment

when it arrived at Baton Rouge. There, on July

15th, they were mustered out. The next day they

boarded the Lady Gay and started north

to rejoin their friends and families.

~*~*~

McLane, James Alfred

Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860 and General

Beauregard’s cannon fired on Fort Sumter on

April 12th of the following year. War followed

and thousands of men died from wounds or disease

and thousands more had to be discharged. In the

summer of 1862, President Lincoln called for

another 300,000 volunteers to fill the depleted

ranks and Iowa was given a quota of five new

regiments. If not raised by the middle of August,

a draft was likely. With the fall harvest

approaching, Governor Kirkwood was concerned but,

if necessary, he said, “the women can

help.” Answering the President’s call,

the quota was met. The 21st Regiment of the

state’s volunteer infantry was mustered into

service at Camp Franklin in Dubuque on September

9, 1862, with a total of 985 men including 84 who

had enlisted early in the year for the 18th

Regiment but, when it was over-subscribed, were

transferred to the 21st.

On a rainy September 16th, they boarded the

sidewheel steamer Henry Clay and two

barges tied alongside and started downriver where

they would serve six months in Missouri before

participating in the Vicksburg Campaign. By then

James McLane, born in Illinois on May 9, 1841,

was twenty-two years old and Mary Elizabeth Pugh,

born on June 29, 1847, also in Illinois was

sixteen. On July 2, 1863, they were married and

two days later Vicksburg surrendered to General

Grant’s Northern army.

As the war continued, the 21st Iowa saw service

in Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas and Tennessee

before moving to Kennerville, Louisiana, in

January 1865 while recruiting efforts continued