EARLY DAYS OF THE REGIMENT

The 36th Iowa Infantry

Regiment, US Volunteers, was one of several Midwestern volunteer

regiments raised in Iowa, Illinois and Wisconsin in the late winter,

spring and summer of 1862 by Illinois Congressman (Lincoln friend and

later General) John McLernand. Companies A and K consisted of men from

Monroe County, while Companies B, C, D, E, F G, H and I were made up of

men from Appanoose and Wapella Counties. The first recruits were

mustered into state service in February 1862. The ranks were filled out

with additional recruits by early September, and the regiment was

officially designated the 36th Iowa Infantry Regiment.

Colonel Charles W. Kittredge of Ottumwa Iowa was placed in command.

Colonel Kittredge had previously served as a Captain with the 7th

Iowa Infantry Regiment in Missouri during the first year of the war and

was an experienced combat veteran.

All companies rendezvoused

at Camp Lincoln, Keokuk Iowa where, on 4 October 1862, they were sworn

into United States service for a term of three years. The men were first

issued old Austrian and Belgian smoothbore muskets with "sword"

bayonets, but these antiques were eventually replaced with more

effective Enfield rifled muskets. Following four weeks of basic training

at Camp Lincoln, the regiment departed Keokuk on 1 November 1862 aboard

two steamboats for St. Louis to await corps and division assignment and

to continue training.

ST. LOUIS, MEMPHIS AND HELENA

At St. Louis, the

regiment went into garrison at Benton Barracks. The 36th was attached to

the 13th Corps, Army of Tennessee, and commenced drill by brigade and

division. On 20 December 1862 they embarked by steamer for the federal

garrison at Helena, Arkansas. The vessel halted at Memphis when the

local citizens hailed it from shore with an alarming report that

Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest and his cavalry were in the

neighborhood and were preparing an attack on the city. That night the

men of the 36th slept with their arms stacked nearby in Jackson Square.

The regiment eventually moved to some old vacated mule-sheds and

remained in Memphis performing guard duty at Fort Pickering until 1

January 1863, when it resumed its movement to Helena.

At Helena, the regiment

became part of the 1st Brigade, 13th Division, 13th Corps under General

Benjamin Prentiss. The regiment was initially quartered in tents but

later moved into winter quarters at Fort Curtis in semi-permanent

“half-cabins” consisting of log walls with canvas ceilings and dirt

floors. These billets had formerly been occupied by the 47th Indiana

Infantry. According to Captain Seth Swiggett of Company B, the

ex-Postmaster at Blakesburg, Iowa, the Iowans devised an efficient

central heating system in these cabins by burying a length of stovepipe

beneath the dirt floor and running it the length of the cabin from a

small tin stove on one end to an exhaust pipe on the opposite end. With

5 to 8 men occupying each cabin, the regiment passed the month of

January 1863 in as comfortable a manner as could be expected under the

circumstances.

THE YAZOO PASS EXPEDITION AND FIRST ACTION AT SHELL

MOUND, MISSISSIPPI

In February 1863, the 36th

Iowa, 600 strong, embarked with other elements of the 13th Corps for

Mississippi to take part in the Yazoo Pass, or Fort Pemberton

Expedition. This operation was conceived by General Grant and entailed

blowing an opening through the east bank of the Mississippi River near

Moon Lake below Helena to open a channel connecting with an inland water

route that would enable Grant to encircle the Confederate stronghold at

Vicksburg from the north. Sergeant Michael Hittle of Company A, a

21-year-old farm boy from Lovilia, Monroe County, recalled years later

that during this expedition the regiment had to wade in ice-cold water

waste-deep. The regiment saw its first action at Shell Mound,

Mississippi where, after witnessing a fierce artillery dual between

federal and rebel batteries, Captain Swiggett noted that the 36th Iowa

had a "sharp exchange" with the rebels.

The regiment was engaged on

this march for 40 days. They found no unguarded route to Vicksburg and

the expedition was abandoned. The men suffered greatly because of

almost continuous exposure to the elements on this campaign, including

freezing rain and high winds that blew their tents down. The constant

cold and dampness thus took a heavy toll with dozens of soldiers brought

down by cold, flu and fever.

THE BATTLE OF HELENA

Returning to Helena, the

36th commenced a physically demanding daily regimen of drill and

building fortifications in anticipation of a Confederate attack expected

with the arrival of spring weather. The 36th Regiment was assigned to

build breast works and trenches in support of Battery A at Fort Curtis,

on the northern most end of the Union defenses. The federal line ran in

a semi-circle around the town with the Mississippi River being their

east flank.

On July 4, 1863, a

Confederate force under General Holmes estimated at between 8,000 and

10,000 attacked Helena. With devastating artillery fire and additional

fire support from the U.S. Navy gunboat Tyler anchored in the

river offshore, the Union positions repulsed the assault in a savage,

bloody all-day slugfest under a burning hot sun. The Confederates

nearly captured some of the federal redoubts where the fighting devolved

into gory hand-to-hand combat. Confederate losses were estimated at

2,000-3,000. The next day the 36th Iowa and its sister units celebrated

Independence Day a day late by collecting and burying rebel corpses.

Vicksburg also surrendered

to Grant on 4 July. These two victories ended further serious

Confederate threats to federal operations along the Mississippi River

and essentially cut off regular lines of communication and supply

between rebel forces on opposite sides of the Mississippi for the

remainder of the war. With New Orleans, Vicksburg, Helena, Memphis and

St. Louis all in federal hands, the Mississippi became the unfettered

transportation and supply nexus of the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army.

Meanwhile, the Army of the Potomac under General George Meade celebrated

a grand if bloody victory at Gettysburg Pennsylvania on the Fourth of

July-- a battle that marked the high tide of the Confederacy in the

eastern theater.

DUVALL'S BLUFF, PINE BLUFF AND THE CAPTURE OF LITTLE

ROCK

Following the battle at

Helena, the 36th became part of the 7th Corps under command of Major

General Frederick Steele and was sent into garrison duty at the federal

supply base at DuVall's Bluff, Arkansas, on the White River. In July

and August, the regiment was sent on a guard assignment to Pine Bluff,

Arkansas. In early September 1863, Steele's corps, including the 36th,

launched its attack up the Arkansas River, converging on Little Rock

and, after a running battle with Confederate troops, captured that city

on 10 September 1863. The 36th Iowa Infantry Regiment went into bivouac

on the grounds of the Arkansas state capital and endured a bitterly cold

winter there. Meanwhile the Arkansas state officials had moved their

capital to the county courthouse at Washington, Arkansas nearer to the

Texas-Louisiana border.

THE CAMDEN EXPEDITION OF THE RED RIVER CAMPAIGN

In March 1864, General

Steele received orders to move his 7th Corps through southern Arkansas

and proceed to attack Shreveport, Louisiana to link up with Union forces

under command of General Nathaniel Banks. Banks had already commenced a

campaign up the Red River of Louisiana aimed at capturing Alexandria,

converging upon Shreveport and, after linking up with Steele, the

combined Union force would push into Texas. It was hoped that Steele's

southward thrust from Little Rock would catch Confederate Commander E.

Kirby Smith in a pincer movement, force Smith to fight a two-front

action and thus divert precious Confederate resources from the main line

of battle on the Red River.

Departing Little Rock on 23

March, Steele's Corps of about 20,000 troops, including the 36th Iowa

Infantry Regiment, immediately encountered rebel resistance in the form

of skirmishers along the line of March. The first major engagement took

place as Steele’s column was crossing the Little Missouri River. The

Confederates had burned the only bridge across the swollen river, so

federal scouts had located the only passable crossing in the vicinity at

Elkin’s Ford. The rebels lay in ambush at the ford and viciously

attacked as the federals made their crossing. A sharp infantry and

artillery exchange ensued in which the 36th played a key

role. After an all-day fight, the rebels abandoned their effort and

withdrew. The federal column continued to be harassed as it proceeded

slowly to the southwest. The Confederates again attacked in force as

the federals emerged into open country on the Prairie D'Ane near

present-day Prescott, Arkansas. As before, the Confederates harassed

and then retreated into the forests and rugged Ouchita Mountains.

These attacks slowed

Steele's progress and the Corps managed to move only 82 miles in 10

days. Facing the unexpected resistance, and growing dangerously short on

supplies, Steele placed all troops on half-rations and decided to divert

his force to Camden, with the hope of resupplying his Corps from local

granaries and mills.

MASSACRE AT POISON SPRINGS

Steele moved into Camden on

15 April with almost no resistance and, discovering that the rebels had

destroyed all the steam gristmills near Camden except Britton's Mill a

few miles south of town, Steele ordered the 36th Iowa Infantry Regiment

to seize the mill. The men of the 36th spent the next several days

engaged in a critical task of protecting the mill and grinding corn meal

for the army.

Steele meanwhile had sent

scouts foraging for other sources of grain and food, and word soon

reached his headquarters that a large cache of corn had been discovered

northwest of Camden on the upper Washington Road near Poison Springs. On

17 April, Steele ordered the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment,

elements of three Kansas cavalry regiments, a section of light artillery

and 198 wagons there to collect the grain. The next day as the loaded

federal wagons were getting underway for the return to Camden, the

escort was ambushed, encircled, cut-off and virtually wiped out. The

federals suffered more than 300 casualties, including 204 wounded. True

to the threats of Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Government, Negro

troops received no quarter in this battle. Most of the enlisted men of

the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry were shot down after they had already

surrendered. General E. Kirby Smith, who had arrived in Arkansas on 19

April witnessed the collection of prisoners and later admitted in his

after-action report that, "not more than 2 were Negroes." Such was the

savagery found in the western theater of operations during the Civil

War.

Steele meanwhile received

news that Banks' force was now in full retreat along the Red River in

Louisiana. The implication was obvious: with Banks withdrawing rapidly,

Kirby Smith could turn the full force of his Confederate Army northward

to attack Steele's smaller 7th Corps as it lay-- completely cut off from

supplies and reinforcements-- miles inside the snake-infested swamps and

pine forests of southern Arkansas. Steele knew that his position at

Camden was tenuous at best. He would certainly receive no reinforcement

from Banks, who was in full retreat in Louisiana, and he would have to

fight his way out of Camden to re-occupy Little Rock or face starvation

and annihilation by the Confederates. Steele decided to save his army.

The odds were completely

against him. While Steele's Corps consisted of 20,000 battle-hardened

veterans, they were now down to just half-rations of hard tack,

quarter-rations of salt-pork and coffee. Furthermore, the disaster at

Poison Springs had resulted in the loss of nearly 200 supply wagons and

the mules to pull them, exacerbating further resupply and foraging

efforts. To make matters worse, after dispatching Banks on the Red

River, Kirby Smith had transferred his command rapidly into Arkansas,

bringing additional infantry regiments with him from Louisiana and

raising some newly recruited units along the way. Smith also had some of

the Confederacy's most creative general officers in the Arkansas

Theater, including the talented Sterling Price, John Marmaduke, Samuel

Maxey, cavalry commander James Fagan and his bold and aggressive

division commanders-- Joe Shelby and William Cabell.

DISASTER AT MARK'S MILLS

A 200-wagon supply train

arrived at Camden from the federal base at Pine Bluff on 20 April, but

it only carried half-rations for ten days. With supplies short, Steele

ordered Lt. Colonel Francis Drake, Commanding Officer of the 36th Iowa,

to take temporary command of the 2nd brigade to escort these wagons back

to Pine Bluff. At Pine Bluff, Drake was to refill the wagons and escort

the train back to Camden.

The train would be heavily

escorted by the 36th Iowa, Major A.H. Hamilton in temporary command, the

1st Indiana Cavalry and elements of the 5th Missouri Cavalry, the 43rd

Indiana and 77th Ohio Infantry Regiments and a four-gun light battery

from Captain Peetz's 2nd Missouri Light Artillery. The 1st Iowa Cavalry

Regiment, which had served its 3 years and was on its way home on

furlough and for re-enlistment, was scheduled to follow and catch up

with Drake's train. The brigade also included a section of 75 civilian

Negro pioneer laborers whose job it was to move ahead of the train,

felling trees and laying them down to build corduroy roads over the

muddy, difficult route. The train with escort left Camden on Friday, 22

April and Drake soon found that an additional entourage of some 50-75

civilian wagons carrying teamsters, sutlers, cotton speculators, about

300 Negro refugees and other assorted camp followers had joined the

expedition. Due to very muddy road conditions, progress was slow and

according to Company B's Captain Seth Swiggett, the column was harassed

by rebel skirmishers and snipers throughout Saturday and Sunday. By

mid-afternoon Sunday, Drake's column had reached the western approach to

the Moro River —essentially a large creek that habitually went out of

its banks in a wide swath during spring rains. Swiggett recounted in his

memoirs that, while no surface water could be discerned in the Moro

Bottom, the ground was so saturated by the recent rains that anyone or

anything attempting to cross it would become hopelessly buried deep in

mud and muck.

Steele had ordered Drake

not to attempt to cross the Moro Bottom after dark, and additionally,

the civilian teamsters were starting to get out of hand, complaining to

Drake about the rigors of the pace, according to Swiggett. Rather than

proceed, therefore, Drake halted the column on the west bank of the Moro

Bottom. In his official after-action report, Drake stated that he

stopped the column that Sunday “evening.” The timing is very much in

dispute, for Captain Swiggett later noted in his memoirs that the column

halted long before nightfall and in fact had gone into camp on the west

bank at 2 pm Sunday. Captain Swiggett opined that, had Drake exhibited

more backbone by insisting on moving across Moro Bottom Sunday

afternoon, the entire train could have crossed safely before nightfall,

would have been well on its way to Pine Bluff, and would have avoided

the tragedy to come. Although Drake could perhaps claim later that he

was technically following Steele's orders by going into bivouac when he

did, Swiggett noted that there was a strong sense of gloom and

foreboding in the federal camp as they lay there immobile on Sunday

afternoon. As it was, Drake posted cavalry squads of 25 troopers each 2

miles to his front and 5 miles to his rear on Sunday, with orders for

them to scout all roads for 5 miles in all directions at daybreak on

Monday.

Sunday night passed without

incident and, having received no reports of the enemy from his scouts on

Monday morning, Drake ordered the march resumed. The 43rd Indiana

Infantry Regiment was deployed to lead the way, while the 36th Iowa

marched on the flank of the wagons. Drake ordered the 77th Ohio to form

the rear-guard and that regiment lagged almost 3 miles to the rear. As

the column crossed the Moro Bottom with difficulty and headed to higher

ground, federal scouts informed Colonel Norris in command of the 43rd

Indiana that they had discovered signs of large, hastily abandoned

cavalry encampments to their immediate front. Norris sent that report

back to Drake, who dismissed it rather curtly and sent forward orders

for the 43rd to pick up the pace. A short distance further,

in a clearing at a fork in the road occupied by a few log cabins, the

43rd Indiana was fired on by dismounted rebel cavalry from General

Fagan's command. Fagan had evaded Union scouts the previous night by

crossing the Ouchita River below Camden and making a forced march of 52

miles to get into position ahead of Drake’s train between the Moro and

Pine Bluff. That morning they were lying in ambush near the crossroad

clearing, known locally as Mark's Mills, just east of present-day

Fordyce in Cleveland County.

Forming line of battle, the

43rd's Norris ordered his command to charge Fagan's dismounted cavalry.

As the charge commenced, Confederate General William Cabell's mounted

cavalry revealed itself from concealed positions in the trees on the

south, or right flank. What began as a skirmish at around 8:30 am

quickly developed into a very hot firefight with the federals firing in

two directions to beat off the assault. The well-aimed fire from the

veteran federal infantry was devastatingly effective and temporarily

slowed Fagan’s advance. Drake ordered the train to pull off the road

into an empty field and then ordered Major Hamilton to deploy the first

battalion of the 36th Iowa Infantry up and onto the firing line on the

43rd Indiana’s left flank. Just as Companies A, B and C came on line,

the Confederates charged the center and took another devastating musket

volley from the federals. Drake then ordered up Peetz's 2nd Missouri

Battery at the double-quick. As Peetz’s gun crews swung their cannon

into position, the federal infantry was ordered to move to both flanks

to open a hole in the center. This was done with alacrity and Peetz's

gun crews opened fire on the rebels with grapeshot at less than 200

yards. This stunned the Confederates, resulting in a momentary lull in

the battle, but musket fire quickly resumed. As the Iowa and Indiana

infantrymen were concentrating on the rebels to their front and right

flank. General Joe Shelby's cavalry brigade swooped down on them from

the left flank. Three companies of the 36th Iowa, the entire 43rd

Indiana and Peetz’s battery were now pressed on three sides and were in

danger of being encircled. Drake ordered the remainder of the 36th Iowa

Infantry, still positioned near the wagons, to charge into Cabell's

troopers on the right to push them back, prevent encirclement and

attempt a link-up with the 77th Ohio, which was now moving forward to

join the battle. Before this charge could be accomplished however, the

rebels closed the trap. As the federal troops were surrounded, it

quickly became a confused entanglement of small units fighting small

units and then it became, according to Captain Seth Swiggett, "Every man

for himself."

The federals fought bravely

but were now surrounded and receiving fire from all sides. The fight was

hotly contested and veterans reported that it lasted fully 5 hours.

Some men of the 36th

Iowa’s first battalion took cover in the log cabins and kept up a

withering and deadly fire, holding out from those protected positions

until long after the others had surrendered, and until they exhausted

their ammunition. When the insurgents threatened to burn the cabins

down, the Iowans surrendered. In his after-action report, Cabell stated

that 17 prisoners were taken from the larger of the two cabins.

According to Captain Swiggett, when capture became certain, most of the

Iowa men smashed their rifles against trees rather than hand them over

to their captors.

As the men of the 36th and

43rd Indiana were being rounded up and dis-armed, a last ditch effort to

break into the Confederate ring by some brave federal cavalrymen created

enough confusion and a diversion for some of the Iowa soldiers to bolt.

Several disappeared into the nearby woods and a few headed to the rear

to warn the 77th Ohio of the overwhelming size of the enemy force to the

front. Reaching the 77th a mile to the rear, the 36th Iowa men were

accused of being deserters and their report was not believed. The

Commanding Officer of the 77th ordered his regiment forward

at the double quick into the melee and soon that regiment was also

overwhelmed by the three rebel cavalry divisions and surrendered.

The men who escaped,

including Third Sergeant Michael Hittle of Company A, evaded re-capture

by moving across country, carefully avoiding rebel patrols. Half

starved, exhausted and unarmed, some reached the safety of Union lines

at Pine Bluff, while others managed to reach Little Rock. There they

reported the news of what had befallen their comrades at Mark's Mills.

Colonel Powell Clayton, the federal commander at Pine Bluff, reported to

General Sherman a few days after the battle that 186 Union cavalry and

about 90 federal infantrymen had managed to escape and report in at Pine

Bluff and at Little Rock. The 36th Iowa Infantry had ceased

to exist by 3 pm on April 25, 1864.

THE BATTLE OF JENKINS' FERRY

Learning of the disaster at

Mark's Mills, Steele immediately put the 7th Corps in motion

from Camden on the morning of the 26 April with the object of crossing

the Saline River at Jenkins’ Ferry and retiring to Little Rock. The

corps made a forced march northeastward to the Saline, where high water

necessitated the installation of a rubber pontoon bridge. Steele then

moved his army across the swollen river, one wagon at a time, one gun

limber at a time, and had three quarters of his trains and artillery on

the opposite bank when his rear-guard regiments were strongly attacked

by the pursuing Confederates. In a savage battle that ranged through

plowed fields on the south bank of the Saline, Steele's troops poured

volley after volley into the pursuing insurgents, first stalling their

attack, and then turning it and buying time for the lead elements of the

column to cross the pontoon bridge. Union infantry then made their

crossing and took up guard from the opposite bank. Steele ordered the

pontoon bridge to remain in place two more hours to enable wounded men

and stragglers to be rescued. Then the bridge was destroyed in place,

and allowed to sink into the river. While Steele's Corps got bogged

down on muddy roads north of the Saline, it managed to make a safe

withdrawal to Little Rock.

While the majority of 36th

Iowa Infantry troops were captured at the Battle of Mark's Mills, some

men of the 2nd Brigade-- including 36th Iowa men who had been left

behind sick in quarters at Camden-- were not present with the regiment

at Mark's Mills. When Steele abandoned Camden therefore, these 36th Iowa

remnants were assigned to a Casual Detachment under the command of

Captain Marmaduke Darnall of the 43rd Indiana, and these men fought

bravely with the Casual Detachment in the Battle of Jenkins' Ferry.

PRISONERS OF WAR AT CAMP FORD

Fully three fourths of the

36th Iowa Infantry Regiment was captured or killed at the Battle of

Mark's Mills. The survivors were robbed of every valuable item they

possessed, including, in some cases, the clothes on their backs and the

shoes on their feet. Overall, they were very roughly handled by their

captors, according to Captain Swiggett. They were force-marched to the

rebel prison at Camp Ford in Tyler Texas where dozens of them perished

from disease and malnutrition over the next 12 months. A number of the

36th Iowa's officers escaped. Captain Swiggett twice escaped but was

re-captured on both occasions and was rewarded for his bad behavior by

being one of the last prisoners exchanged.

Those who survived the

horrors of Camp Ford were repatriated in April 1865 and these survivors

returned to DuVall's Bluff. There, along with the handful of men who

had escaped capture the year before, the 36th Iowa Infantry Regiment was

re-constituted. The regiment saw no further combat action and completed

its service guarding the depot at DuVall’s Bluff.

The regiment was mustered

out of federal service at DuVall's Bluff 24 August 1865. The veterans

returned north to Davenport, Iowa where they received their final Army

pay before dispersing to their respective home counties.

POST-SCRIPT

The Union Army never

controlled the territory of Southern Arkansas, but it occupied the

capital and effectively took the state out of the war for all practical

purposes and contained the threat to Missouri from Shelby and other

Confederate raiders in the final two years of the war.

Lieutenant Colonel Francis

Drake, whose bad judgment and weakness in command led to the disaster at

Mark's Mills, was wounded by a musket ball to the hip and captured

there. As senior Union officer in command, the rebels exchanged Drake a

few weeks after his capture. He returned to Iowa to a hero's welcome and

he subsequently used that as political capital to win election as

Governor of Iowa. Contemporaries from his service days, including

officers and men alike from the regiment and from other regiments

engaged at Mark's Mills were far less complimentary toward their former

acting brigade commander. Men of the 43rd Indiana Infantry Regiment, in

particular, held Francis Drake in contempt for his actions at Mark's

Mills, accusing him of leading them straight into ambush by his

dithering indecisiveness in failing to cross the Moro Bottom on the

afternoon of 24 April.

The official 7th Army Corps

report for the battle of Mark's Mills listed the 36th Iowa Infantry

Regiment's casualties as 18 men killed or wounded and 371 captured.

According to Company K’s Sergeant Josiah Young's history of the

regiment, however, 49 men were either killed outright or subsequently

died of wounds suffered at Mark's Mills.

Confederate General William

Cabell perhaps spoke the greatest compliment to the men of the 36th Iowa

Infantry Regiment when he noted in his official after-action report

that, ''The killed and wounded of Cabell's Brigade show how stubborn

the enemy was and how reluctantly they gave up the train. [My] men never

fought better. They whipped the best infantry regiments that the enemy

had...old Veterans as they were called."

The regimental colors of

the 36th Iowa Infantry are on display in the rotunda of the

Iowa State Capital in Des Moines.

APPENDIX I

OFFICERS OF THE 36TH IOWA INFANTRY AT MARK'S MILLS, 25 APRIL 1864

LIEUTENANT COLONEL FRANCIS

M. DRAKE, ACTING COMMANDER, 2nd BRIGADE *

MAJOR A.H. HAMILTON, ACTING

COMMANDING OFFICER, 36th IOWA INFANTRY REGIMENT *

MAJOR COLIN M. STRONG,

SURGEON *

MAJOR STEVEN K. MAHON,

ADJUTANT *

MICHAEL H. HARE, CHAPLAIN *

CAPTAIN JOHN M. PORTER -

COMPANY A *

CAPTAIN SETH A. SWIGGETT -

COMPANY B *

CAPTAIN ALLEN H. MILLER -

COMPANY C *

CAPTAIN THOMAS B. HALE -

COMPANY D *

FIRST SERGEANT HENRY SLAGLE

- COMPANY E *

CAPTAIN WILLIAM F.

VERMILLION - COMPANY F *

CAPTAIN THOMAS M. FEE -

COMPANY G *

LIEUTENANT JAMES W.

THOMPSON - COMPANY H *

CAPTAIN JOSEPH B. GEDNEY -

COMPANY I *

CAPTAIN JOHN LAMBERT -

COMPANY K *

* CAPTURED AT MARK'S MILLS

25 APRIL 1864

APPENDIX II

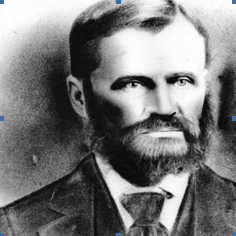

A BIOGRAPHY OF SERGEANT

MICHAEL HITTLE

COMPANY A

36th IOWA

INFANTRY REGIMENT, USV

Sergeant Michael Hittle was

born April 4, 1841 in rural Rush County, Indiana, the first-born of

Jacob and Huldah Jane (Ambers) Hittle. Between the age of five and

seven years Michael relocated with his parents to the new community of

Bremen (later changed to Lovilia), in Kishkekosh (later Monroe) County,

Iowa. Mr. Hittle’s grandfather, also named Michael, had purchased

government-owned homestead parcels in Monroe and other eastern Iowa

counties since 1845, and the extended Hittle family including Mr.

Hittle’s grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles were among the first

settlers to arrive in Monroe County from Indiana and Illinois between

1846-1848.

Michael Hittle received

only about 3 months’ of schooling in one-room schools houses on the

Indiana and Iowa prairie. On December 29, 1860, he married Miss Deborah

Barnard, a native of Putnam County, Indiana at Lovilia.

On September 7, 1862, Mr.

Hittle was mustered in as 4th Corporal of Company A of the 36th

Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment at Albia Iowa, alongside his father,

Jacob, also a volunteer.

Sergeant Hittle rose

through the non-commissioned officer ranks and was discharged as 3rd

Sergeant of Company A on August 24 1865 at DuVall’s Bluff, Arkansas.

He was engaged in all of the marches, expeditions and combat actions of

the regiment, with the exception of Jenkins’ Ferry. This was due to the

fact that he had been taken prisoner five days earlier at the battle of

Mark’s Mills but was one of the fortunate 90 infantrymen who escaped and

made their way to Union lines which, in Sergeant Hittle’s case, was

Little Rock. Thus he was not present with the remnants of the 36th

Iowa who were part of Captain Darnall’s Casual Detachment that fought at

Jenkins’ Ferry on April 30 1864.

Following his discharge

from the Army, Sergeant Hittle returned to Monroe County and resumed his

occupation of farming, working leased ground in and around the community

of Lovilia for the next 14 years. In 1879, he made a three-month trip

through Western Iowa, Kansas and Colorado to examine homestead land,

eventually deciding to settle in Monona County, Iowa. In 1880, he

purchased 240 acres northwest of Castana, in Kennebec Township. He

eventually increased his holdings to 306 acres on which he was actively

engaged in stock raising. He was a member of the Christian Church and

belonged to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) veterans’ posts at

Lovilia and Castana. He and his spouse had eight children of whom four

grew to maturity—Thomas Jefferson Hittle, Andrew Michael Hittle, Newton

Albert Hittle and Clara Ann Hittle (McGee). In 1885, his mother and

father came to live with him in Monona County.

On March 21 1900, Mr.

Hittle collapsed unexpectedly, the victim of an apparent heart attack.

He was 58 years of age. He is buried in Lot 1, Block 3 of Grant

Cemetery, Grant Township, Monona County, Iowa.

Sergeant Michael Hittle

1841-1900

APPENDIX III

A BIOGRAPHY OF CORPORAL

JACOB HITTLE

COMPANY A

36th IOWA

INFANTRY REGIMENT, USV

Corporal Jacob Hittle was

born in Greene County, Ohio on June 6, 1820, the seventh child of

Michael Hittle and Lydia (Yeapel) Hittle who originally hailed from

Columbia County, Pennsylvania. Jacob Hittle was the grandson of Michael

Hittel Senior of Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, and he was a great

grandson of Jurg Michael Hittel, a native of the German Rhineland who

immigrated to Northampton County Pennsylvania in 1738. Jacob’s great

grandfather, Michael Hittel Senior, was a veteran of the Revolutionary

War, having served on campaigns in Captain John Santee’s 8th

Company, Fifth Battalion, Northampton County Pennsylvania Militia in

1778 and 1780. Mr. Hittle’s uncle, George Hittle, was the first White

pioneer to settle on Sugar Creek in Tazewell County Illinois, founding

the community of Hittle’s Grove and Hittle Township, in 1826.

At two years of age, Jacob

Hittle relocated with his parents from Ohio to rural Rush County,

Indiana, where he grew to manhood. On June 1, 1840, Mr. Hittle married

Miss Huldah Jane Ambers, daughter of Kentucky natives William and Sara

Groves Ambers, at Rush County. Between 1846 and 1848 Mr. Hittle and

his wife relocated to Iowa to join his father, mother and brothers and

their families and were among the earliest settlers in the town of

Bremen (later renamed Lovilia), Kishkekosh (later Monroe) County, Iowa.

Mr. Hittle was a carpenter by occupation, a Mason, and a member of the

Christian Church. He is believed to have been involved in constructing

many of the buildings of the new community at Bremen-Lovilia.

On September 7, 1862, Mr.

Hittle was mustered in as 6th Corporal of Company A, 36th

Iowa Volunteer Infantry, along with his son Michael Hittle. Corporal

Hittle rose steadily in the non-commissioned officer ranks, being

promoted 5th Corporal on September 1, 1863, to 3rd Corporal

on August 11, 1864, to 2nd Corporal on November 16, 1864 and

to 1st Corporal on June 10, 1865. He was discharged from the

regiment along with his son on August 24, 1865. Corporal Hittle was

engaged in all of the marches, expeditions and combat actions of the 36th

Iowa Infantry Regiment with the exception of the Yazoo Pass expedition,

when he remained in quarters at Helena due to illness, and the action at

Mark’s Mills, when again he had been left sick in quarters in Camden.

Having thus avoided the

disaster that had befallen the 36th Iowa at Mark’s Mills,

however, Corporal Hittle did take part in the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry

on April 30th 1864 as a member of Captain Darnall’s

provisional Casual Detachment, which played a prominent role in that

engagement.

Corporal Hittle returned to

Lovilia after the war. He and his spouse had nine children of whom six

were raised to maturity: Michael Hittle, from whom the author is

descended, Sarah Ann Hittle (Ross), George Levago Hittle, Philip Hartzel

Hittle, Mary Survilla Hittle (Egbert), and Silas M. Hittle.

In 1885, Mr. Hittle and his

wife moved to their son Michael’s holding near Castana, Monona County,

Iowa, where Jacob died in 1905. He had been a member of the Grand Army

of the Republic (GAR) veteran’s posts in Lovilia and Castana, Iowa. He

is buried next to his son, Sergeant Michael Hittle in Lot 1, Block 3,

Grant Cemetery, Grant Township, Monona County, Iowa.

Corporal Jacob Hittle

1820 - 1905

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| 1. |

Bearss,

Edward., Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’

Ferry. (Little Rock: Pioneer Press, 1961). |

| 2. |

Christ,

Mark, ed., Rugged and Sublime, The Civil War In Arkansas. (Fayettville:

The University of Arkansas Press, 1994). |

| 3. |

Swiggett, Seth. The Bright Side of Prison Life. (Baltimore:

Fleet, McGinley & Co., 1897). |

| 4. |

US

Government Printing Office. The Official Record of the War of the

Rebellion (OR), Series I, Vol. XXXIV, Part 1, Official Reports,

pp. 665 - 713. |

| 5. |

“Biographical Sketch of Michael Hittle,” in A History of Monona

County, Iowa. (Chicago: National Publishing Company, 1890). |

| 6. |

Army

Pension Record of Jacob Hittle. File Number: SC 634.135,

National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| 7. |

Army

Pension Record of Michael Hittle. File Number: WC 533.587,

National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| 8. |

Young,

Josiah T., Sergeant, “History of the Thirty-sixth Iowa Infantry,” in

An Illustrated History Of Monroe County, Iowa. (Chicago:

Western Historical Company, 1896). |

AUTHOR NOTE

Jon B. Hittle is

originally from Woodbury County Iowa. He received a B.A. in History

from Briar Cliff College in 1973 and an M.A. in Modern European History

from Louisiana State University in 1976. He has a dozen direct-line

ancestors who served in Iowa and Illinois regiments during the Civil War

and he has been conducting research on those regiments for the past 25

years. He was a Military Intelligence Officer working out of

Washington, D.C. for 30 years before retiring in May 2009. His

military service consists of 6 years of active and reserve duty in the

US Coast Guard