11th Regiment Iowa Infantry, Company D

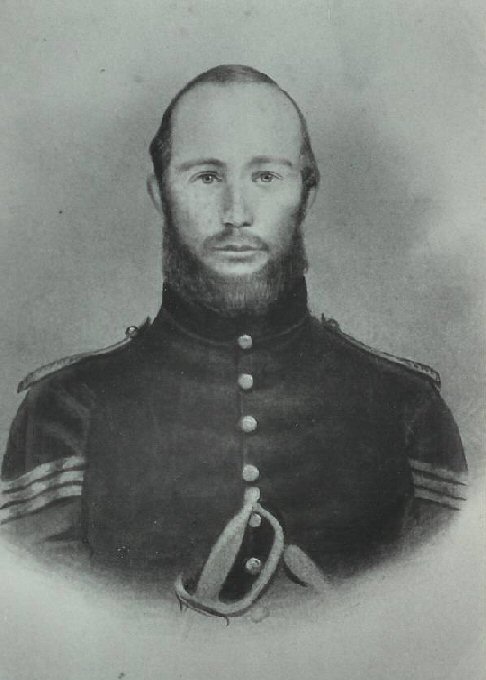

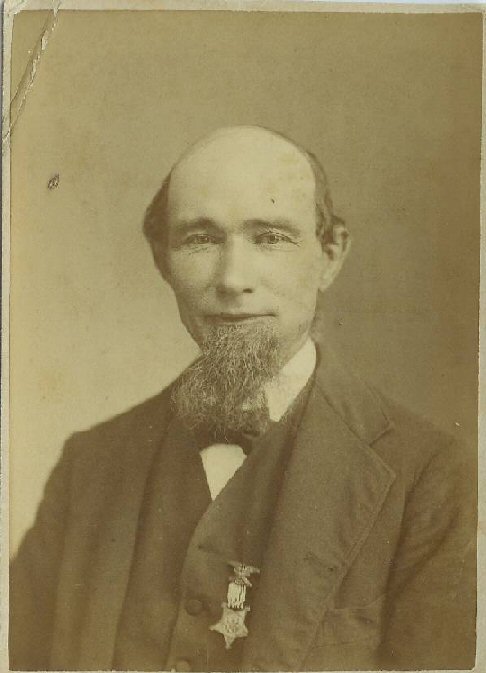

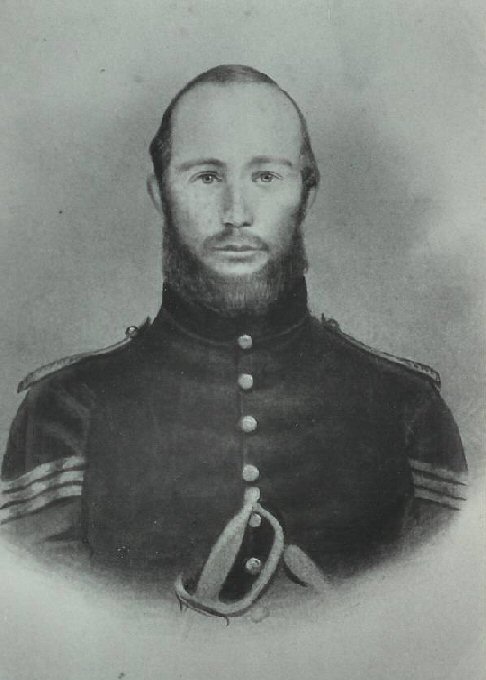

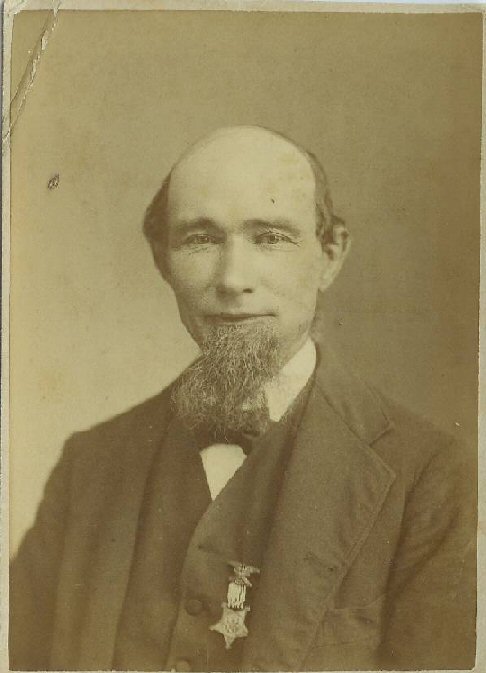

Civil War Photo Civil War Reunion Photo on right

|

THE LIFE OF ENOS BEECHER CHATFIELD

Enos Beecher Chatfield was born in Oxford, New Haven Co., CT on Mar 5, 1828. His father was Enos Chatfield and his mother was Roxy (Sperry) Chatfield. In all of the references to him in his adult life, and in his signatures, the Enos was dropped and he was referred to as Beecher Chatfield. In a letter to his father-in-law, he signed it B. Chatfield. Beecher, like his father, was a bricklayer and stone mason. He met Mary Elizabeth Seymour, and married her in Oxford, CT, on Sep 14, 1852. Beecher called her Lib. Mary Elizabeth was born in Massachusetts on Nov 14, 1833, but lived in Dubuque, Iowa at the time they married. Her father was William A. Seymour and her mother was Sarah Dunham. Her maternal grandmother was Lucy (Ariail) (Dunham) (Hart) Stearns (1781-1867), who lived in Oxford, New Haven Co., CT, and it is believed she was either living with Grandmother Lucy, or visiting her, when she met and married Beecher in Oxford, New Haven Co., CT Beecher and Lib were living in Seymour, CT, where their first child Frederick Seymour Chatfield was born on Dec 24, 1853. A second child, William Howard Chatfield was born on Oct 11, 1854, but he died on Jul 10, 1855. William Howard is buried in Wilton, IA. It is for certain that sometime between Dec 1853 and July 1855 Beecher and Lib removed from Connecticut to Iowa. On Jun 11, 1856, Beecher bought a piece of property from W. R. Newton in Wilton Junction, IA, now known as Wilton, IA. He paid $1 for Lot 2 of Block 7 of Peter Marolf's Addition to Wilton, IA. A daughter, Lucy Ariel Chatfield was born on Jul 27, 1856, in Wilton Junction, IA. Lucy was the first child born in Wilton Junction. A HISTORY OF WILTON JUNCTION, IOWA

It will always be remembered, with patriotic pride, that Wilton responded nobly. Two full companies were organized in Wilton of nearly two hundred men. The first was Company D, of the Eleventh Iowa Volunteer Infantry. The second was Company G, of the Thirty-Fifth Iowa Volunteer Infantry. The first Company (D) was organized in September, 1860, and was officered as follows: A.J. Shrope, Captain; B.F. Jackson, First Lieutenant; Andrew Walker, Second Lieutenant. They were a fine body of men and received their baptism of fire at the battles of Pittsburgh Landing and Shiloh, the killed and wounded being nearly one-third of the force of the Company. Appended is a list of those killed, and who died afterward of wounds received in those battles. Henry Seibert, Thomas J. Cory, Peter Craven, Wm. Leverich and Wm. White were killed, and John A. Hughes, George Miller, Beecher Chatfield and R. R. McRea were severely wounded at the battle of Shiloh, April 6th, 1862. Van V. Reeves was wounded at Lovejoy's Station, Georgia, and Perry Starrett at Kenasau (Kennesaw) Mountain. The Company "went veteran" at Vicksburg, in February, 1863, numbering thirty-six, under the following commissioned officers: Andrew J. Shrope, Captain, Augustus C. Blizzard, First Lieutenant, and James M. Kean, Second Lieutenant. In March, 1863 they came home under command of Lieutenant Kean, on furlough, and were joyfully received by friends and relatives. Speeches, dinners, and a good time generally was the order for the ensuing thirty days, at the end of which time they returned to the field where they joined Sherman's forces (then moving on Atlanta) at Ackworth, Georgia, and were under fire eighty-four days in succession.They continued with Sherman through Georgia and the Carolinas, and took part in the grand review at Washington, at the close of the war. In the year 1862, a draft was talked of, and a notice was given that every person between the ages of eighteen and forty-five years must report to the Medical Board, at Muscatine to be examined as to their ability to do military duty, and it was during this examination that the remarkable discovery was made that all but two, who were able-bodied men had enlisted. -Above from "History of Wilton, 1876"- Beecher enlisted in the 11th IA Infantry on Sep 14, 1861, and arrived at Camp McClellan, near Davenport, IA for muster on Oct 3, 1861. For readers that are not knowledgeable about the terms used for the opposing sides in the Civil War, Beecher was a northern soldier in the Union Army (USA), and would be called a Yankee by a Southerner. A southerner would be in the Confederate Army (CSA), and would be called a Rebel (or frequently called a Sesh, short for a secessionist). The 11th IA is a Regiment, it was composed of ten companies with each company having about 100 men. A Brigade consisted of several Regiments. A division consists of several Brigades, and several divisions would make a unit called an Army. The Army of Tennessee was the Union group that Beecher was in during the Battle of Shiloh, but the North also had the Army of Ohio, and the Army of the Potomac. Beecher left at home his 27 year old wife with 7 year old Freddy, 5 year old Lucy, and 3 year old Anna, and (probably unknown to him and Lib) an unborn child, Sarah Henrietta Chatfield who would be born on June 18, 1862. The 11th IA Regiment consisted of ten companies, and at the time of muster (organization) it consisted of 922 men. Beecher was made Third Sergeant of Company D. The 11th IA Infantry was the first regiment armed and equipped before leaving Iowa. Honoring the funeral of Lt. Colonel Wentz of the Seventh Iowa (killed in battle at Belmont, Missouri), it presented IA citizens their first view of a marching regiment in army blues. Abraham M. Hare, who had been a major of militia in Ohio, was the regiment's first colonel. Wounded at Shiloh, he resigned, and the regiment's history was largely made under Col. William Hall. Col. Hall was educated at Oberlin College and the Western Military Institute of Kentucky. He studied law at Harvard. In 1864, when Colonel Belknap was promoted ahead of him to General, he resigned in a huff. When during its days at the Davenport, IA camp, the regiment complained of having "nothing to eat" except baker's bread, fresh beef, vegetables, apples and cucumber pickles, the Muscatine women produced cake, fruit, roast turkey, chicken salad, boiled ham, tongue, and mince pie in such lavish amounts, the regiment's command almost passed to the medical officers. In the lean years ahead when the men were living off a country already stripped to the bone, they looked back with longing on the days of their "Iowa famine". The Muscatine newspaper editorialized about the barracks' leaky roofs and the lack of sanitation at the camp. While at Camp McClellan, Davenport, IA the regiment made some progress in drill (marching and handling of their rifles) and in learning the duties of the soldier. On Nov 16, 1861 the troops boarded the riverboat Jennie Whipple for St. Louis. Now their complaint was exposure to the cold and snow. On Nov 19, 1861 the regiment arrived at Camp Benton in St. Louis, Missouri. I n St. Louis, smallpox, measles, mumps and acute homesickness developed, the last more devastating than the others. On Nov 27th, 1861, while at Camp Benton, Beecher wrote the following letter to his father-in-law. Camp BentonDear Father I thought I would send you a few lines to inform you where I was and what I was about. I am a Soldier in defense of my Country at present at these Barracks. I enlisted last Sept the 14th. I have been at Camp McClellan in Davenport until about two weeks since we came down here. There is now about 30 thousand of us here in camp, including all there is about 6 Regiments from Iowa here. We expect to march from here soon for Columbus Kentucky or some other point we hardly know where. I left my family in Wilton and I should like it if you could manage to pay them a visit this winter some time and see how they are getting along. They would no doubt like to see you but they strictly forbid my writing to you about them when I left, but I thought best to write for your presents (presence) might cheer them up. Lib was rather opposed to my coming but I considered it my duty to come, whether it was or not I am not able to say, time will determine that. I am Sergent (Sergeant) of Cop. D of the 11th Regt. Col. A.M. Hair (Hare) of Muscatine, probably you know him, he that was Maj. Hair (Hare). If you get this letter you must answer it the next mail if you possibly can. Go down and see how the affairs are getting along at Wilton, it would give me a great deal of ease for you know nothing how it worries me a thinking about their welfare and cheer them up for I think the war will soon close or it will be hard on the south. Secesh (secessionists) is on all sides of us here. Gen. Fremont left here yesterday, God forbid that ever another as good man should leave under such circumstances as he did, the best commander that ever was west of the Mississippi. Gen. Halack (Halleck) is now under command. The IA 7th is in a bad condition, nearly all cut to pieces. There is not enough of it left to make a good company. The 12th is at your place yet I suppose. I left rather in confusion. There was at that time talk of drafts and I dreaded that. If you answer this I will write again soon and let you know how we prosper, but do go down and see how they get along. I am not concerned but what they will have enough to eat but to cheer them up and see to things. It is getting late and time to crawl (under) the covers. Yours truly B Chatfield

Note: The original letter contained no punctuation, which I added to make it more readable.

While at Camp Benton, the regiment received instruction in drill and camp duties, in which it became fairly proficient before taking the field for active service against the enemy. The regiment left St. Louis on Dec 9, 1861 and from that date was engaged in a winter campaign, and suffered much from hardship and exposure. It went first to Jefferson City, MO, and then went up the Missouri River to Boonville, from which point it sent out scouting parties, but only found small groups of the enemy. The enemy having horses and familiar with the country, scattered upon the approach of the Union infantry troops. The regiment soon returned to Jefferson City. On Dec 23rd, 1861, a detachment of five companies was sent by rail to California, MO, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Hall. The other five companies, under command of Colonel Hare, went to Fulton, Missouri. While the records do not show any official report of the operations of these two detachments during the remainder of the winter, and while no event of special importance seems to have transpired, the service performed was important, because of the fact that the presence of these Union troops insured protection to the lives and property of Union citizens. A large number of rebel soldiers had been raised in that state, and had joined the rebel army then in camp on its southwestern border, while small bands infested almost every county, and many depredations were committed notwithstanding the presence of Union troops. The Muscatine Journal said the greatest danger of the winter campaign occurred when five hundred green soldiers and a reckless crew rode a train loaded with 173 kegs of gunpowder which the cavalry captured at Boonville. SHILOH BEGINS TO UNFOLD One night in January, 1862, General Halleck chatted informally at his St. Louis headquarters with Brigadier Generals Cullum, his chief of staff, and William T. Sherman. The conversation turned to a discussion of where the Union army should attack the Confederate army. Halleck placed a large map in the table, took a pencil, and asked Cullum to draw a line across the map where the Confederate line lay. Cullum ran a pencil mark through Bowling Green, Forts Donelson and Henry, and on to Columbus, KY. "Now," Halleck asked, "where is the proper place to break it?" Both Sherman and Cullum were aware that others were urging a major campaign down the Mississippi River, yet they were equally aware of the Confederate strength at Columbus, Kentucky, where General Leonidas Polk (CSA) had fortified the river bluffs with tiers of heavy guns. After a moment's hesitation either Sherman or Cullum spoke up and said, "Naturally, the center." Halleck then drew a line perpendicular to the other, through the middle of Cullum's line. It ran almost parallel with the course of the Tennessee River. "That," he announced, "is the true line of operations." Early in March the two detachments of the Eleventh IA were ordered to St. Louis and, on March 10, 1862, the regiment was again united, and two days later was being transported by steamboat down the Mississippi to Cairo, and then up the Ohio and Tennessee rivers to Savannah, Tennessee, where it remained until Mar 23rd. On Mar 23rd, the 11th IA moved to Pittsburgh Landing, and became a part of the large army then being concentrated at that point and destined to soon be engaged in one of the greatest battles of the war. The 11th Iowa was assigned to the First Brigade of the First Division of the Army of the Tennessee. Maj. General Ulysses S. Grant was the commander of the Army. Maj. General John A. McClernand commanded the division, and Colonel A. M. Hare of the 11th IA was in command of the First Brigade. Colonel Hall took command of the 11th IA, since Colonel Hare was placed in command of the Brigade. For this battle, the Army of Tennessee consisted of six Divisions, and totaled 39,830 men. Near Pittsburgh Landing the land was spectacular. Deep ravines, often with small creeks rushing toward the Tennessee, cut through the rolling hillsides. Two large and swollen creeks, (Owl and Lick), dominate the region, creating in effect a rough triangle of campground that extended for three miles before being interrupted by a range of two-hundred-foot-high hills south of the landing. Lick Creek runs along the northern edge of these hills joining the Tennessee about two miles south of the landing. Since the Tennessee River at this point runs almost due north, it nearly parallels the high ground along the landing and forms the eastern side of the triangle. The area is often marshy in the spring. About a half-mile north of Pittsburgh Landing the second large creek, Snake Creek empties in to the Tennessee River. Although Snake Creek continued to the west, its course was directed away from the landing. A large Snake Creek tributary, Owl Creek, cuts across the rolling tableland from the southwest, however, forming the western boundary of Sherman's Pittsburgh Landing campground. Both Lick and Snake creeks were treacherously deep in the spring, under flood conditions Owl Creek might reach a depth of thirty feet, but four feet was more normal. Sherman saw this triangle of land as a strategic position and "an admirable camping ground." The terrain, although noted by Sherman to be of "easy defense by a small command," was not chosen for its defensive value. Foremost in Sherman's mind was the establishment of an offensive base of operations. "I ... acted on the supposition that we were an invading army," he wrote. "The position was naturally strong ... we could have rendered this position impregnable in one night, but ... we did not do it. ... To have erected fortification would have been evidence of weakness and would have invited an attack." Since Sherman's recommendation had led to the concentration at Pittsburgh Landing, he, more than any other officer, was responsible for the army's presence there. More importantly, as the unofficial camp commander he was in charge of the organization and defense of the camp. As the various divisions and regiments arrived, they were assigned sites throughout the triangle, most of the new units camping near the landing. The 11th Iowa's campsite was on Jones Field, near the west side of the Union camp. No fortifications were ordered built. Across the 3 1/2 mile southern base of the triangle, from Lick Creek to Owl Creek, only Sherman's division guarded the outer perimeter. Between Stuart's brigade and Sherman's main encampment at Shiloh Church a gap of more than a mile existed, to be filled by a yet unorganized division. On each side two swollen creeks barred passage. In the army's rear the broad Tennessee swirled wildly by, and rapid evacuation or reinforcement was hindered by the limited landing space below the buffs. At Corinth, MS, Twenty-two miles away, a large Confederate Army was quickly forming. Sherman, despite his calculating plans, had unknowingly placed the Federal army in a natural trap. To the men going ashore from the cramped confines of an Army transport the camp at Pittsburgh Landing was a welcome sight. The weather, which had been cold and rainy, briefly turned very warm toward the end of March. Most of the Federal soldiers found their regimental camps to be quite comfortable and well equipped. Each company was provided with five large Sibley tents, pitched close together in a row. For the officers a smaller square tent was erected at the head of each row. Ovens made of dried clay were set up to bake fresh bread. Hospital tents were erected, as was a quarter-master's tent for the storage of regimental supplies. Some regiments even had potbellied stoves made of sheet metal to heat their tents. Throughout the first week in camp most of the time was consumed in clearing campsites, bringing up supplies from the Landing, and improving the camps with such refinements as elevated bunks made from tree poles, so the men might sleep off of the ground. The job of unloading troops and their equipment and supplies at Pittsburgh Landing was more difficult than first planned. High water restricted the landing area so much that Sherman had to back his boats away in order to allow Hurlbut's troops to land on March 18, 1862. When other Federal troops arrived, they found the landing area hopelessly jammed. One commander observed that Pittsburgh Landing was "occupied with boats for its entire length, five deep." By the time C. F. Smith's division arrived the landing area was so congested that one of his brigade commanders, Brigadier General John McArthur, carved out a separate landing area and road in order to speed the unloading process. So many thousands of troops were found crowding about the landing that it was necessary for Sherman to move Buckland's and Hildebrand's brigades out to the Purdy road camps on Thursday, Mar 20. By the end of the week the tents of Sherman's division stretched for nearly a mile through the lightly timbered woods along the Purdy road. On their far right ran Owl Creek, rain-swollen and out of its banks, choking the adjacent ravines with backwater and ankle-deep mud. A long, dry ridge ran along the Purdy road before falling away into a lowland marsh near the Owl Creek bridge. A little more than a mile east of this bridge, in the midst of Sherman's camps, the main Pittsburgh-Corinth road intersected with the Purdy road. Nearby, on the main Corinth road, a small group of Southern Methodists had erected a one-room cabin of sturdy logs, "chinked and daubed." It was named Shiloh Meeting House, after Shiloh, "A Place of Peace," from the Bible, First Book of Samuel. For nearly ten years the local residents had gathered there to observe the Sabbath. Their little log chapel was built of oak with hewn walls and a clapboard roof, both of which had long since weathered and cracked. Several hundred yards behind the Meeting House, south of the crossroads, Sherman established his headquarters tent. Sherman called his camp "Camp Shiloh" and soon started a daily routine of drill, inspection, and reviews. Grant so far had relied on the judgment of Generals Smith and Sherman in organizing the camp at Pittsburgh Landing. On March 19, 1862, however, he steamed upriver to inspect the camps at Crump's and Pittsburgh Landings. Crump's Landing was a small camp that was organized shortly before Pittsburgh Landing, and was four miles north of the Pittsburgh Landing. Lew Wallace's units were at this camp. Returning that night to Savannah, Grant was satisfied and reported to his superior Gen. Halleck in St. Louis that the two sites were "the only ones where a landing can be well effected on the west bank ..." so far as was known. He was careful to add, however, that this only applied "to the present stage of water." Of greater importance to Grant was the dispatch from Halleck that was waiting for him upon his return. Halleck had received a telegram on the Mar 17 from General Buell (Commander of the Union's Army of Ohio) in Nashville in which Buell claimed to have "reliable" information that the Confederates, twenty-six thousand strong, were marching "to strike the river below Savannah, to cut off transportation." Halleck's deceptively ambiguous note to Grant said that if this was true, "General Smith should immediately destroy (the) railroad connection at Corinth." Grant realized that the flooded rivers prevented extensive enemy operations and dismissed the possibility of Confederate artillery getting close enough to annoy the river transports. He telegraphed Halleck, however, that "immediate preparations" would be made to advance on Corinth according to his instructions. Grant added that he would go in person, leaving McClernand in command at Savannah. When told the next morning that it would take another four or five days to land all of the troops at Pittsburgh Landing because of the restricted landing space, Grant estimated that he would be able to begin his advance by Mar 23 or Mar 24. In anticipation McClernand was ordered to send two of his brigades on to Pittsburgh Landing and to have the third follow as soon as a garrison could be organized at Savannah from the new arrivals. Several Confederate deserters had just been brought in, and from them Grant learned "that thirteen cars (had) arrived at Corinth on the nineteenth" (March 19) with enemy reinforcements. Noting as well that the roads were almost impassable for artillery and baggage wagons, Grant delayed his plans to advance. Yet the Confederate deserters convinced him that Rebel morale was poor and that when attacked, "Corinth will fall much more easily than Donelson did ...." Early on the morning of April 6, 1862, the camps of General John A. McClernand had bustled with the usual routine of Army life. Following breakfast, the men began preparing for inspection, tidying their tents and polishing their brass-adorned equipment with fine ashes. There was the prospect of a clear, balmy day, and many of the men were in a good mood. "It is good to be here," wrote an Iowa soldier, who considered "what money many would gladly spend to be able to witness the magnificent view our encampment present(s)." The surroundings seemed a little more pleasant on this morning. A number of visitors were in camp, including the wife of Colonel William Hall of the 11th Iowa. In an Illinois regiment the young son of a captain had just arrived for a visit. It seemed that the camp would spend a pleasant Sunday preparing for a future battle at Corinth. The calm was first broken by the sound of gunshots far in the distance. Soon began the "blood curdling sounds", so one soldier thought, of the "long roll." In a little while several cannon shots passed over the camps, followed by others that plowed up the ground and tore through the tents. Trees were splintered nearby, and a shell struck a horse in the hind leg, mangling it's hoof. Men scattered in all directions. Wagons and teams were seen hurrying to the rear. When a projectile from a rifled cannon whistled close above an Iowa volunteer, it seemed to warn of an impending disaster. McClernand's first reaction had been to send a courier to Sherman asking what all the firing was about. Then, as most of his division listened with growing concern to the roar of the guns, McClernand went to see for himself. Hare's brigades, which included Beecher's regiment, being camped farther to the rear, were at the time still formed on their parade grounds awaiting orders. Soon thereafter McClernand hurriedly sent orders for Hare's and Marsh's brigades to advance to the front. Marsh's brigade, being camped nearest to the front, was the first to advance, marching in direct support of Sherman. After approaching the right rear of Sherman's camps, they were halted, and orders soon came to countermarch. The men later learned that McClernand had belatedly decided to put his two brigades into line farther to the east, along the ridge that ran in front of his headquarters. Here the main Corinth road paralleled the ridge after making a sharp turn to the northeast about a quarter-mile north of Shiloh Church. A short distance south of the Corinth road lay an open field, used for reviews, spanning about twenty acres. Marsh's brigade had already taken its designated position along the road when Hare's men came up. Since McClernand wanted Hare formed on his left, his men had to pass behind the already deployed line to reach their destination. While the rest of Hare's Brigade was positioned to the east of Marsh's Brigade, the 11th Iowa was detached from the brigade at the very beginning of the battle and during both days received it's orders direct from Generals Sherman, McClernand, and Grant, and at no time was the regiment directly connected with any other unit during the battle, except Dresser's Artillery Battery. In front of McClernand's troops, including Hare's and Marsh's Brigades, Sherman and Prentiss's divisions met the charging enemy. McClernand, about a quarter-mile on the rear, was warned of the enemy's approach by Captain Warren Stewart of his staff, who had made a hasty reconnaissance and escaped under a heavy fire to deliver his report. Hare's brigade (without the 11th Iowa) was just then moving along the edge of the review field south of the Corinth road, coming up to take position on McClernand's left. As they filed along the skirt of woods, the Confederates, advancing along the opposite side of the field, opened fire. The range was considerable, about two hundred yards, but a few Federals were hit, including the two senior captains commanding the 18th Illinois. Quickly Hare's line was formed, the men standing in tense anticipation of an attack. Down the line to the right cannons were roaring, enveloping McClernand's battle line in smoke. Marsh's brigade was defending this sector, a 300 yard front bordering on the main Corinth Road. Here four regiments totaling 1,514 officers and men had deployed along a ridge, supported by three full batteries of field guns, the artillery forming the backbone of Marsh's line. Plugging the gap between Hare and Marsh stood McAllister's battery of four 24-pounder howitzers. Burrows's 14th Ohio Battery was ready near the center of Marsh's position, while Dresser's six-gun battery (and the 11th Iowa) protected Marsh's right. Another Illinois battery, Schwartz's, was firing from near the crossroads in support of Sherman's line. In appearance McClernand's line was formidable, but the men were nervous. The attack began at the strong point, on Marsh's front. "The enemy were seen approaching in large force and fine style, column after column moving on us with a steadiness and precision which I had hardly anticipated," wrote the breathless Marsh. The Confederate brigade of S.A.M. Wood (CSA), continuing its turning movement after the retreat of Prentiss, was first to appear despite the severe punishment it had taken in the advance toward this new Federal front. Although Raith's (USA) brigade had broken up at the approach of these heavy Confederate columns, including Weed's, A.P. Stewart's, and Shaver's troops, numerous tactical mishaps had already fragmentized the Confederate battle line. Following the accidental wounding of Wood (CSA) by his own men, his staff officers hastily attempted to re-form the brigade. Much of the trouble occurred on the brigade's left flank, where the Confederates were so disorganized that at least one regimental commander had his men fall down behind cover on the side fronting the enemy to avoid a fire from "friendly" troops in the rear. Although the left remained stalled, the Confederate right flank now began to press onward. Their attack was supported by several batteries, including Bankhead's Tennessee (CSA), firing opposite Burrow's position (USA). Not far from these cannons lay the 4th Tennessee of A.P. Stewart's (CSA) brigade, hugging the ground for protection. When their general came up, he was inspired. Stewart said he had just talked with one of Bragg's (CSA) staff officers, who pleaded that the battery in front must be taken. "I turned to the 4th (Tennessee); told them what was wanted; (and) asked if they would take the battery..." Stewart recalled with pride. Back came the reply, "Show us where it is; we will try." Going forward under the eye of Stewart (CSA), the 4th Tennessee (CSA) sprinted unsupported into the blasts of canister. Men fell right and left. According to their commander 31 men were killed and 160 wounded during this fateful charge. "If you ever heard the little yellow dogs (brass field guns) bark," said an excited Federal participant, "... (I) guess they did some of it there. The fire flew out of their mouths in clouds." Crossing from the open field into a growth of light timber to avoid this deadly fire, the 4th Tennessee approached the Federal line at the double-quick. "We were within 30 paces of the enemy's guns when we halted, fired one round, (and) rushed forward with a yell..." wrote an officer. Ahead, the 45th and 48th Illinois (USA) were inside the edge of the woods on Marsh's (USA) extreme left, supporting McAllister's (USA) battery. The men were standing in line, apparently unable to see very well through the billowing battle smoke, when the 4th Tennessee suddenly loomed in front. The enemy came nearer, but no one gave the order to shoot. "What does it mean? Why don't our officers give the command to fire?" stammered a private. With the two lines only pistol range part, the strain became unbearable. Several infantrymen raised their muskets and fired into the oncoming ranks. "Cease firing!" shouted an officer as he rushed along the line. "Those are our troops." Realizing that the flag of the Tennessee regiment had been mistaken for a Federal flag, some of the men pleaded with their officers that it was a mistake. The officers still insisted they were Federal troops. "The hell they are!" roared an excited private. "You will find out pretty damned soon...." By now it was too late. The Confederates were within a stone's throw, and they threw up their muskets and fired a point-blank volley. "Our men fell like autumn leaves," wrote an embittered Union private. Another eyewitness, a Federal colonel, later said this fire was so devastating he thought it unequaled during the entire battle for destructiveness. "During the first five minutes I lost more in killed and wounded than in all the other actions," commented a saddened Marsh (USA) in his official report. The 48th Illinois (USA) was the first to break. Both the colonel and lieutenant colonel were hit, and the entire regiment went to the rear in confusion. "In spite of my efforts to compel them to stand they fell back..." said Marsh, who became further alarmed when he saw that the panic was spreading to his remaining regiments. Other Confederate battle lines were now seen approaching in successive waves. Some of Wood's (CSA) troops, including the 16th Alabama and 27th Tennessee, began to head for Burrow's (USA) guns. The break up of the Federal line was spontaneous. McAllister's (USA) guns were exposed by the retreat of their supports, allowing the 4th Tennessee (CSA) to approach on their right flank. The Rebels were about to surround his battery when McAllister (USA) gave the order to prepare to retreat. Yet so many horses had already been killed that one gun had to be abandoned. McAllister (USA) took four slight wounds, but he got his three remaining howitzers rolling, just before the 4th Tennessee (CSA) swept through his battery. One 24-pounder howitzer and two soldiers, "who did not have time to escape nor courage to fight," said a Confederate officer, fell into the enemy's hands. Burrows's (USA) battery of 6 and 12 pounder Wiard rifles was next to take a pummeling. Their infantry supports also had become panic-stricken by the growing chaos and already had gone to the rear. Burrows's (USA) cannoneers were confronted by Wood's (CSA) troops, among them the 16th Alabama and 27th Tennessee, who raised a yell and charged for the guns. Seventy horses went down amid the battery. The underbrush and trees were chopped to pieces in front. McClernand (USA), who watched nearby, saw his orderly shot down. When Burrows (USA) and several of his officers fell, the battery became helpless and was captured in entirety. The last of Marsh's (USA) regiments, the 11th Illinois, had been fighting only ten minutes when they saw the sudden retreat taking place on their left. Immediately the 11th Illinois's line also disintegrated. "(They) fell back, I regret to add, without my order," wrote Colonel Thomas Ransom of the 11th Illinois. Nearby stood McClernand's (USA) third battery, Dresser's Battery D, 2d Illinois Light Artillery, commanded by Captain James P. Timony (USA). Their guns had been positioned by Major Taylor (USA) of Sherman's staff just to the east of a small pool known as Water Oaks Pond, with the 11th Iowa in close support. Their opponents proved to be several of Bushrod Johnson's (CSA) detached regiments, the 154th Tennessee and Blythe's Mississippi Regiment, coming up from the vicinity of Waterhouse's captured battery. The Tennessee regiment was directly in the 11th Iowa's front, moving at a measured pace. Here an Iowa sergeant watched wide-eyed as they approached. "The regiment that was advancing against us was evidently an A No. 1. One look at them was enough to convince a man that courage and discipline are virtues peculiar to neither North or South," said the sergeant. "Without a waver the long line of glittering steel moved steadily forward, while, over all, the silken folds of the Confederate flag floated gracefully on the morning air." The fighting opened with a roar from the artillery. Timony's (USA) guns were served so well that they later earned the praise of Sherman's chief of artillery. "(The fire here was) the most terrific... that occurred at any time during the fight," said Major Ezra Taylor (USA). Indeed, so many horses were shot in their harnesses that all the guns could not be moved in the emergency that followed. With a determined effort the Confederates forced their way among the battery, enduring terrific losses at every step. Several intact teams that had just been hitched to the guns now bounded off without their drivers, the frightened horses dashing through the lines of infantry and scattering the men. Nearby, the 11th Iowa's major had been shot in the head, and its commanding officer unhorsed. The Confederates were threatening to surround the regiment on the right when the 11th Iowa hastily scattered, three of its companies becoming separated in the chaos. Four guns of Timony's battery were overrun where they stood, completing the near destruction of McClernand's artillery. Beecher Chatfield received a severe wound to his right leg on this day, and this point of the battle was the worst that the 11th Iowa was involved in on April 6. While the 11th Iowa would join other units in a fierce battle about an hour later, the majority of the unit's casualties were injured during this exchange of gunfire. A great disaster now seemed in the offing. Marsh's (USA) brigade was a shambles. McClernand's (USA) line was pierced in the center, and his whole line had begun to break up. On Hare's (USA) front the Confederates had simultaneously advanced in a massed attack. The dapper, five-foot-one-inch-tall Hindman (CSA), inspired by Johnston's (CSA) promise of another star, had ordered an immediate advance when he came up and found the Federals posted along the ridge across Review field. Hindman led in person, at the head of Shaver's (CSA) brigade and one of Russell's (CSA) regiments, the 12th Tennessee. When some of Shaver's (CSA) men protested that nearly all of their ammunition had been expended during their recent fight with Prentiss (USA), Hindman stopped them short. "You have your bayonets," he said. The charge carried directly across the open field at Hare's (USA) troops, and the field was soon strewn with dead and wounded. Before Hindman's (CSA) men could close with Hare's (USA) infantry, this Federal line also began to crumble. "We gave them one round of musketry and (we) gave way," later wrote a Federal colonel. One of Hare's regiments fell back without firing a single volley. Even the 8th Illinois (USA), on Hare's extreme left, was thrown into disorder, caused by the stampede on their right. The brigade, already weakened by the detachment of the 11th Iowa, was further fragmentized during the retreat when the 8th Illinois fell back in a different direction. The situation by now was desperate, and only circumstance intervened to save McClernand's division. Following Sherman's (USA) urgent request for reinforcements about 7:30 a.m., Hurlbut (USA) had sent Colonel James C. Veatch (USA) with nearly three thousand infantry to go to Sherman's support. Veatch's brigade was soon started along the main Corinth road for the front, the men marching "with unusual briskness," wrote an officer. As they approached Review field shortly after 9 a.m., an officer rode up in great haste and directed them to move behind Marsh's (USA) brigade, already formed in the woods beyond the Corinth road. Veatch's (USA) men quickly moved behind the deployed line, supporting Burrows's (USA) battery from the rear. A few minutes later the enemy attacked, and Marsh's (USA) troops were routed. Burrows's battery was "belching like a volcano" noted an officer, who watched spellbound as a tall sergeant stood alone to double- shot a cannon and fire it into the faces of the onrushing enemy. Then the battery's loose horses and mules bolted to the rear, through Veatch's (USA) line, throwing the 14th Illinois (USA) into disorder. An officer of the regiment, Lieutenant Colonel William Camm (USA), looked up. "I could see the Johnnies (rebels) running from tree to tree, and popping away at us as they came," said Camm. Volleys crashed along the regiment's front, but the 14th Illinois's (USA) colonel thought he saw an approaching line of men dressed in blue uniforms. Fearing that they were his own men, he gave the order to cease firing. A moment later the mistake was recognized and the fighting resumed. "The enemy (was momentarily) checked but was very stubborn, and we murdered each other...at close range," Camm (USA) continued. "Our brigade commander, General Veatch, rode down the line and I asked him to turn us loose with the bayonet. "No, no," he said, "you would lose every man." My horse was struck behind the saddle and lunged among the men so that I let him go. Throwing myself in front of the colors, (I) tried to get the men to charge, but between us was a struggling mass of wild and wounded battery horses, many of them harnessed to the dead, and I could not get them started." A Confederate private who had participated in the Review field attack remembered this, his first battle, as a painful experience. The fighting, he thought, "was an awful thing.... It terrified my mind to hear the guns..." and he reflected that he had not words strong enough to describe the conflict. "Oh, God," was his prayer, "forever keep me out of such another fight." The private was not mistaken--the volume of Federal fire had been tremendous and the carnage dismaying. Wood's (CSA) brigade was inoperative following the charge. Its commander had been knocked senseless when dragged by his runaway horse through a captured camp. His staff attempted to handle the brigade in his absence, but the regiments were so wasted as to be unmanageable. The 27th Tennessee (CSA), near Wood's (CSA) right, had suffered as much as any regiment in the brigade. Its colonel had been shot in the chest and killed, just as some of his men were struck from behind by a volley fired by other attacking southern regiments. A captain was put in command, and when the casualties were counted, the losses amounted to half the regiment. The brigade was so scattered that when the 16th Alabama (CSA) advanced to the right to attack Veatch (USA) following the replenishment of their ammunition, they found no support and had to await the arrival of Shaver's (CSA) brigade. Most of the Confederate regiments led by Hindman had already been so bloodied that there was little further incentive to resume the advance until compelled to do so. About fifty minutes had been consumed by the attack, and it was now nearly eleven o'clock. Some of the Confederate regimental commanders, left to their own devices, ordered a halt and rested in the captured camps while "awaiting orders." One of Wood's (CSA) colonels reckoned that his men had been fighting for five hours, and he ordered them to rest. Others marched their men to the rear to find ammunition and stayed there until ordered back to the front. Even Shaver (CSA) regarded his men as too exhausted to continue. His ammunition was running low, and he received permission to fall back to Raith's (USA) captured camps, to "supply my men with ammunition, rest my men, and await further orders." Worse still, for a while no one seemed to be in command in this sector. Hardee (CSA) had been there, along with Bragg (CSA), but just before Hindman was disabled, Hardee had gone to the right, satisfied that Hindman was "conducting operations...to my satisfaction." Bragg (CSA) also had departed following Hindman's (CSA) attack on Veatch (USA), considering that the brigade could do no more. He already had told Polk (CSA) to take charge of "the center" and assumed Polk would press on, regarding the enemy resistance here "less strong" than toward the right. Polk (CSA) was dismayed to find only three brigades in position to fight following the impromptu transfer of command. Moreover the troops were so scattered that none of these brigades was intact, some being reduced to two regiments in line. The Federals had fled in several directions following the breakup of McClernand's line, complicating the tactical problem of pursuit. Moreover logistical problems continued to disrupt serious attempts to mount an attack. Not only was ammunition in short supply, but regiments such as the 4th Tennessee found their muskets so fouled by powder residue that they could not be loaded. The result was a disjoined, spasmodic effort on the part of some Confederate units to resume the offensive, while others went to the rear for a rest. A.P. Stewart (CSA) took two regiments, one of which belonged to another brigade, and swung to the northeast along the Corinth Road. Attacking Veatch's (USA) position soon thereafter, this weakened column was unable to make headway. Russell (CSA), too, found his troops badly scattered. With only two regiments he went in the opposite direction against Raith (USA), their path carrying them northwest toward the "crossroads." Here they joined a portion of Bushrod Johnson's (CSA) and Anderson's (CSA) brigade in a bloody struggle for the important intersection of the Hamburg-Purdy and Corinth roads. As soon as the fighting abated, entire regiments flung themselves down to rest or went to the rear seeking ammunition. As other troops began pillaging the nearby Federal camps, the entire battleground seemed to be in chaos. The surgeon of the 11th Louisiana (CSA) remembered with anger that "the sight of all these objects (trophies) lying about in such abundance was too much for our men." They were soon loaded down with "belts, sashes, swords, officer's uniforms, Yankee letters, (and) daguerreotypes of Yankee sweethearts..." while others were drunk on "Cincinnati whiskey" and "Philadelphia claret." Crippled by heavy losses and plagued by a breakdown in command and communications, the Confederate left wing was temporarily unable to resume the offensive. William Tecumseh Sherman (USA) had found little solace in the chaos existing amid McClernand's (USA) camps as he fell back about 11 a.m.. Two regiments, the 46th and 49th Illinois (USA), were observed in front, sniping at the enemy across Woolf field. But their position hindered the deployment of artillery, and they were soon ordered back. Once a fire zone had been cleared, Sherman began to pass among his men, reorganizing a battle line. Riding through the pall of smoke nearby was "Sam" Grant, resplendent in his major general's uniform. He soon found Sherman, and the two generals here met face to face for the first time on any battlefield. There was a marked contrast in their appearance. Sherman, his uniform torn and a bloody handkerchief wrapped tightly around his hand, was gaunt and disheveled. His wound was inflamed from constant riding, and the pain had begun to numb his fingers. The thought may have crossed Sherman's mind that Grant would be angry. He had predicted "no attack" at the very time when Grant was relying on him for the utmost vigilance. In consequence the army had been surprised, and presently was in danger of being destroyed. His own division, moreover, had been routed and his camps captured. Sherman, speaking first, mentioned that he had several horses killed under him, and he displayed his torn uniform rent by bullets. This attempt to sway Grant's opinion, if such, was unnecessary. Grant said he thought Sherman was doing well in stubbornly resisting the Confederate attack. Then, indicating that his presence was more needed on the Federal left, he departed following a brief chat. About all Sherman learned from the conversation was that Grant had ordered up a resupply of ammunition and that Lew Wallace (USA) was coming from Crump's Landing with his division. What Grant and Sherman did not know was, Lew Wallace was on the wrong road, and would not arrive at the battle until the next morning. Sherman's troops were slowly pushed back to a small area near the landing area, as were the units from the eastern portion of the battle. Destruction was imminent, but two events were to save the Federal army and prevent Beecher Chatfield from becoming a prisoner. A small group of Federal soldiers on the eastern part of the battle, would take cover on a sunken road. The depression of the road, combined with a rail fence and a long open area in front of them, allowed these brave soldiers to hold the Confederate troops on that half of the battlefield. The Confederates would bring together 62 cannons, the largest concentration of cannons ever seen in an American battle before, and using aerial bursts to kill the Union soldiers behind their protection, forced the survivors to surrender. The other event, thought to be the turning point of the war, was the death of Confederate General Albert S. Johnston. Johnston sent his personal physician to treat wounded Federal prisoners and Confederates. Shortly after, he was rallying his men to attack, when he slowly fell from his horse. His aides began searching him for a wound. He had several insignificant wounds, but the one they did not find was a wound to the back of his right knee. It is possible that Johnston did not even realize that he was wounded there. A modern pathologist reports that Johnston had probably been bleeding for a half hour before he fell from his horse, and a tourniquet applied even 15 minutes after that would have saved his life. Ironically the bullet is believed to have been fired from one of his own soldiers. His death affected the battle of Shiloh directly, in that his command was given to General Beauregard (of Fort Sumter fame), and some of his commanders were confused as to what they should do next. All of the Federal troops were pushed back to a crescent shaped defense line near the landing area. Historians believe that if Beauregard had continued his push, the outcome probably would have been the capture of Grant's entire army. Several things prevented Beauregard from continuing the assault; his troops were tired and began to drift back toward the south, and the sun was beginning to sink below the horizon. Beauregard (CSA), even though he had been warned that Federal General Buell was approaching Pittsburgh Landing with the Ohio Army, did not believe the rumors and thought that he could finish the attack in the morning. Even at that moment, Buell (USA) was at the Landing and his 18,000 troops had began to cross the Tennessee River. Lew Wallace's 7,500 troops also arrived during the night. These reinforcements gave Grant a 54,600 to 34,000 troop advantage for the next day's battle. As horrifying as the day's battles were, that night would in it's way would be worse. The only Federal hospital ship had made several trips to Savannah with wounded during the day, but that was only a small dent in the thousands of federal casualties. All of the transport ships were loaded with wounded soldiers laying side by side, every tent, wagon, or cover of any kind was filled with Union wounded. There was a small house near the landing that the surgeons used as a hospital, during the night the surgeons were busy with their saws and a ghastly pile of amputated limbs grew outside the house. The dead were stacked like firewood outside of this house and the other shelters that the wounded were taken to. Even General Grant could not find shelter during the night. Many of the wounded and dying from both sides could not make it to either army's lines and were left lying in the open. The cries and moans from the wounded in the Union camp and those left on the battlefield mixed as one long wailing that was only partially drowned out by the cold rain that began to fall at around midnight. Some of the Union officers were issued blankets, but no one ate that night. There were many cases of the wounded from both sides crawling into tents together during the night. The men who had been enemies during the day, would talk through the night as they died. Many of the survivors would keep promises made during the night, and deliver letters and messages to the widows of men that had tried to kill them during the day. The Federal gunboats fired their big cannons every 10 to 15 minutes into the Confederate camps. The effect was mostly psychological, and the shooting was intended to keep the Confederates from sleeping. The Federal soldiers who had survived the day, slept on top of their rifles. Their tents and blankets were still in their camps, which were occupied by the Rebels. The men were hungry and exhausted, but there would be no sleep as they lay in the mud and were soaked by a rain that was almost sleet. On April 7, the Federal troops forced the Confederates to retreat, and by early afternoon, the battle was over. THE BATTLE'S AFTERMATH The battle at Shiloh was the largest battle in American History up to that time. The North suffered 1,754 killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885 missing. The South had 1,723 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing. This total was more death and injury than the three previous American wars combined. The American Revolution produced 10,623 American casualties, the War of 1812 caused 6,765 American casualties, and the Mexican War inflicted 5,885 American casualties, adding up to 23,273 American casualties for all 3 previous wars. The Battle of Shiloh produced American casualties of 23,741, which was 24% of the men involved in the fight. Grant's army would move to Corinth, Mississippi and capture it after a much smaller battle. Americans on both sides changed their opinions that this war would be a short series of small battles. McClellan's war plans of small chess like movements and nearly bloodless battles was viewed as naive, and the Union Government supported Grant's conclusion, that the war would not be over until the South was literally destroyed. Beecher would be out of the war after Shiloh. Colonel Hare was also too injured to fight again. The 11th Iowa was placed under the command of Colonel Crocker, and became part of "Crocker's Brigade", one of the fiercest fighting units on either side of the war. The 11th Iowa went on to the Siege of Vicksburg under Grant, and was with Sherman during his "March to the Sea". On August 15, 1862, Beecher was discharged from the army at Keokuk, Iowa. On October 11, 1864, Beecher and Lib had another daughter, Mary Elizabeth Chatfield, but she died December 5, 1864. On January 8, 1866, they had another son, Edward Beecher Chatfield. Edward was born in Dubuque, Iowa. On July 18, 1871, they had another son, Charles Stanley Ross Chatfield. Charles was born in Wilton Junction, Iowa. On May 20, 1872, they had another daughter, Nellie Maud Chatfield. On April 19, 1874, they had another daughter, Emma Gertrude Chatfield. On March 1, 1877, they had a final child, a son they named Townsend. Townsend died in Wilton Junction, Iowa on April 13, 1878. On February 7, 1888, Sarah Henrietta Chatfield, died of Tuberculosis. On November 12, 1892, Beecher was admitted to the Iowa Soldier's Home in Marshalltown, Iowa. The admission form indicates that Beecher had been an Iowa resident for 38 years, had enlisted one time during the Civil War, that enlistment being in August of 1861 as a Sergeant in Company D of the 11th Iowa Infantry under Colonel Hare. The form also indicates that he was discharged in August of 1862 in Keokuk, Iowa and that the cause of his discharge was a gunshot in his right leg. He gave his age as 63, his place of birth as Connecticut, his occupation as Brick mason, his marital status as married, and his residency as Dubuque, Iowa. The examining surgeon stated that Beecher was disabled because of heart disease, and that he was able to care for himself, but was unable to do any manual labor. On January 24th, 1893, Beecher died at the Iowa Soldier's Home. The cause of death was listed as Bright's Disease. Bright's Disease is a disease of the kidneys usually associated with faulty Uric Acid elimination and is associated with high blood pressure. -Obituary notice- "Mr. Beecher Chatfield, a member of Hyde Clark Post, G.A.R., of this city, died yesterday at the Soldier's Home at Marshalltown. He was a member of Co. D, 11th Iowa, during the war and was in several battles." Beecher was buried in Asbury Cemetery, Asbury, Dubuque Co., Iowa. As an afternote: It has been rumored among the descendants of Enos Beecher Chatfield and Mary Elizabeth Seymour that Lib never forgave Beecher for enlisting in the Civil War. Although several children were born after his discharge, the rumor says that at some point they had divorced. This rumor does have some basis in fact as the pension papers for Beecher state his widow as "Olla Chatfield", and an "Olla Chatfield" shows in Dubuque, Iowa Census records as a widow. Again, there is basis in fact from the following newspaper article, no date is given, but it is presumably from the Newspaper in Dubuque, Iowa. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Newspaper Article, no date, no paper name: Probably Telegraph Herald, Dubuque, Iowa. AN AGED HERO MOSES CLEVELAND: A veteran of the War of 1812, who gave 6 sons to the Union. Moses Cleveland, an extremely old man who took part as a youth in the War of 1812, is here on a visit to his daughter, Mrs. B. Chatfield, wife of the well known stonemason. He is the son of Col. Augustus Cleveland of the same war, and furnished six sons to the late civil war. The old gentleman, though lately ill in Milwaukee, appears to be remarkably strong for his years, and may be seen in West Dubuque, where it is probable he will remain. The gentleman's visit was the occasion of a jolly time at Chatfield hall, West Dubuque, last evening, under the management of Mr. Hubert Guthrie and friends. Quinn's band enlivened the young and old with songs and music till daylight appeared. If you can help me identify "Olla Chatfield", I would appreciate your help. Cheryl E. (Chatfield) Thompson, great-great-great-granddaughter of Beecher and Lib 1300 North Church Street Belleville, Illinois, 62221 CharlieChatfield@aol.com |