P. 23

ARMY LIFE

CHAPTER TWO

Conditions of the war when I enlisted----Taking the Oath — Leaving Home—Guarding Indians at Camp McClellan—FromCairo to Vicksburg—Meeting my regiment at Memphis---Joining the Battalion and Guard Duty at Vicksburg—From Vicksburg to Clifton, Tennessee—First marching—Joining my regiment at Huntsville, Ala.—Sherman concentrating his forces for the Atlanta campaign–March to Rome—First line of battle at Kenesaw mountain—Siege of Atlanta—Battle July 21st-22nd –capture of 16th Iowa —Guarding prisoners—Casualties—of battle–Chasing Hood–Camp at Marietta—My first vote–Detailed as provost guard—Destroying railroads—March to the sea–Advance on Savannah–Seven days without rations–Capture of Savannah—Boat trip to Louisville, Ky–Accident to boat–Discharge and muster out.

As nearly fifty years have passed since the close of the great Civil War, it will hardly be expected that I can give in detail all the exciting scenes and incidents that occurred, even in that part of the army to which I belonged. Neither do I expect to describe them as others saw them, as no two persons see exciting scenes alike. In writing this part of my story I shall not rely entirely upon memory, but will be aided in part, by a small pocket diary I kept at the time. I shall not attempt to write a history of the war, but will only undertake to relate, briefly, the part I took in it. The war had been going on nearly three years when I enlisted. Some of its greatest battles had been fought. I believe it is generally conceded, that the defeat of the Confederate forces under Gen. Robert E. Lee at Gettys-

P. 24

burg, July 3, 1863, was the turning point in favor of the Union forces. Up to that time, the battles between the forces were about a draw. In the summer of 1913, during the reunion of the “Blue and the Gray” at Gettysburg, I visited the battlefield and went over the ground where the Union and Confederate forces were engaged the last day of the fight. On the Union line near little Round Top, I saw a stone tablet on which was inscribed “The high tide of the Rebellion reached here.” It was at this point, during the battle, where Gen. Pickett’s division of the Rebel army made the famous charge and was defeated. The next day, July 4th, the Confederate Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to Gen. U.S. Grant. The fall of Vicksburg practically cut the seceded states in two and opened communication to the gulf. Bands of Rebel guerillas infested the banks of the river, lurking behind trees and stumps and firing at our steamboats as they passed, but the Union gunboats soon cleared the river of all these annoyances. Simultaneously, with the fall of Vicksburg, Grant sent Gen. Sherman with a large force to find and disperse the Rebel army under Gen. Joe Johnston. The Rebel general made a feeble attempt to make a stand at Jackson, Mississippi, but soon abandoned the position and made a retreat to the east, leaving the Capital of Mississippi once more in the hands of Union forces. Gen. Grant’s army, at this time, was made up mostly of western men, who had enlisted for three years or during the war. The time of many of them would expire within the next twelve months, and there was little prospect of the war being over in that time. As an inducement for men to re-enlist the government offered a bounty of $#400, and a thirty days’ furlough home. Many of the men re-enlisted and came home during the winter of 186304. They usually came to the states by regiments. Those who did not re-enlisted were called “non-veterans” and were formed into battalions, and retained in the field for guard duty. When I enlisted, Crockers’ Iowa Brigade composed o the 11th, 13th, 15th and 16th regiments was at Vicksburg. My two older brothers, Elijah and Mifflin, volunteered in Company C, of the 11th Iowa, which was organized at Columbus City, and went to the front in September, ‘61. Elijah died at Vicksburg soon after its surrender. At the time of his death, Mifflin was with his regiment in a raid on Meridian,

P. 25

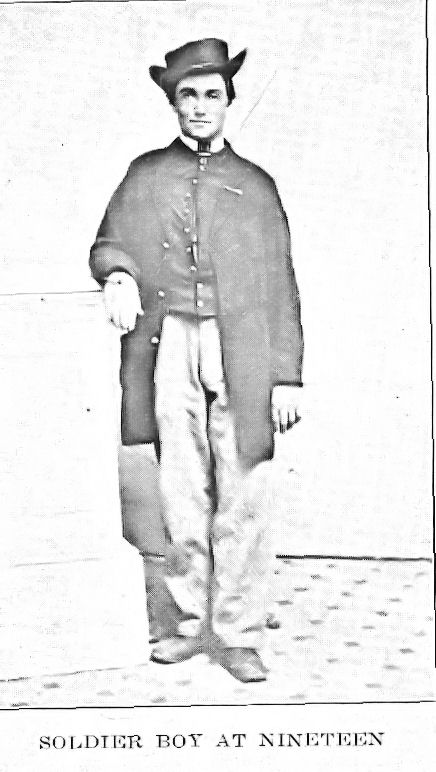

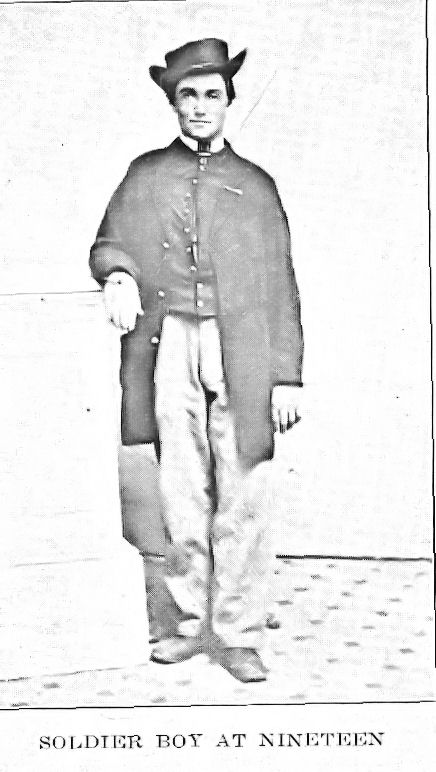

Miss. He re-enlisted about the first of January ‘64. On Sunday my 19th birthday I happened to be at one of our near neighbors and met Jacob M. Ashford, whom for convenience I will call Jake.

He had three brothers in the army who belonged to the same company Mifflin did. During our call the war question naturally came up and Jake bantered me to volunteer, said “he would enlist if I would” After talking the matter over for some time we arranged to go the next day and be sworn in. It stormed Monday so we did not go until Tuesday. Arriving at a county justice of the peace, who lived about a mile from our place, we informed him what we wanted. The justice got his statutes, and began looking for the oath to administer to us, but not finding it, finally said “Boys, hold up your hands.” He mumbled over some words that we did not understand, then said, “You do solemnly swear that you will be good soldiers, won’t you, boys,” and stopped. But that was good enough for us. We remained at home about three weeks. In the meantime, there were many young men in our county enlisting. Most of them were going as recruits for the 11th Iowa. About the 10th of March we got notice to appear at Clifton, a railroad station about eight miles from my home, on a certain day to leave for the front. The day came and I bid goodbye to home folks, to my mother and youngest sister for the last time. Father took me to the station. Arriving there I met Jake and about two hundred other recruits. We took the train and were sent to Davenport, Iowa; then placed in Camp McClellan, about two miles from the city. Next day after our arrival we were put in a room, stripped naked, and examined by an Army surgeon. Jake and I passed and were then regularly sworn into the U. S. Service for three years, or during the war. We drew suits of government clothing and were paid $300 state bounty. We took up daily drill and life in the barracks. At that time there were some two or three hundred Indians held there in a stockade as prisoners, who had taken part in that terrible massacre in Minnesota. At times we were detailed to carry them wood to keep fires. We would carry the wood to the gate in the the stockade and throw it in; ofttimes trying to strike them, but usually they were too quick for us and would

P. 26

dodge it. March 12th, we left camp McClellan, and were put on a Rock Island train and sent to LaSalle, Illinois. Here were changed to the Illinois Central road, put in box cars, so close that we had no room to lie down, and sent to Cairo, Ills. In the evening of the second day after we got to Cairo, Jake and I were down at the wharf when a large boat, “The Mississippi” heavily loaded with soldiers going home on a furlough, landed. The first officer to come ashore was Gen. U.S. Grant. That was my first sight of him. The boat was unloaded, then re-loaded with all kinds of army supplies including wagons, harness, horses, mules, cattle and feed. Jake and I had to help load the boat. We went abroad with about five hundred recruits going to join their regiments. The boat was very heavily loaded, for the water came near to the top of the guards and I was somewhat scared for fear it would sink. It was the largest boat I had ever been on. The boat finally pulled off from shore and headed for Vicksburg. At Memphis we met the 11th Iowa, on their way home on furlough. I met brother Mifflin here. All recruits on our boat went on to Vicksburg. Before we got to Lake Providence, a strong wind came up, driving the water clear across the deck, thru the engine room of the boat, and was nearly knee deep for the stock. It became so violent that we had to land and dip the water out of the boat, and place boards long side. Without further trouble we landed at Vicksburg, March 19th. Jake and I soon found the Iowa battalion, then commanded by Colonel Pomoutz, of the 15th Iowa. We were placed in a company made up of non-veterans of the 11th. While here we did daily drill work and guard duty. My first experience on picket was at an old fort on a hill just outside Vicksburg, on the road leading to Black River.

On March 30th, the battalion left Vicksburg by boat for Cairo, Ill. On our way one afternoon when a short distance below Lake Providence our boat was signaled by some contrabands on shore to land. We were just passing a short bend in the river when the Captain of the boat ordered the pilot to land. When nearing the bank, he reversed his engine, and the lever broke, letting the boat strike the slightly slanting bank with such force as to break the side walls just back of the engine. At the time I was standing on the top deck holding to the flag

P. 27

mast. When the boat struck the bank, the check was so sudden that it came near to throwing me over in front of the boat. At this time there were many guerrilla bands along the river and frequently decoyed boats to land, then pillaged them. Jake and I with others were put on picket while the boat was being repaired to watch for them. In about three hours we proceeded on our trip. April 3rd we landed at Cairo. The boat was unloaded and the battalion marched to near Mound City, but a few miles, where we camped. T he next day Jake and I went to the soldiers’ hospital in the city, and found his brother William. He was badly wounded at Yazoo City, shortly after the surrender of Vicksburg, and sent to Mound City. We remained in camp here nearly a month, drilling most every day. The day before we left, our regiment returned from furlough to Cairo, and Mifflin came to see us. April 28th our battalion was loaded on the boat “Collesus” and that night we pulled off for Clifton, Tenn. The second morning when we got up there were eight boats to be seen in the fleet. We arrived at Clifton, about eight miles below Shiloh, on the 31st and proceeded to unload our. While unloading an amusing incident occurred. Some wagons had been taken ashore and set up, when four mules were hitched to one of them. The mules were restless and finally pulled the wagon past the boat along the river bank before we got the box on. The driver tried t back the mules and in the mix-up they backed the wagon off the bank, and the whole outfit went into t he river out of sight. Shortly the mules came up, snorting and puffing for breath. We got some long poles, pushed them round in front of the boat and rescued them and the wagon. May 5th the battalion left Clifton for Huntsville, Alabama. We started about 4 p.m. and marched five miles before we halted for camp. The day was very warm and it was our first experience marching with our army equipment. Most all the recruits had more baggage than a Jew peddler would pack. Jake and I had drawn a full outfit of government clothing and still had the clothing we had brot from home. We also had our knapsack, guns, cartridge box, forty rounds of ammunition and five days rations to carry, besides many relics we had picked up from the battlefield around Vicksburg, that were intending to take home. But when morning came, we made a general cleaning out of

P. 28

knapsacks. Clothing of every description and war relics were left in camp and scattered along the line of march most all day. Jake and I held to our overcoats until noon, then left t hem. By night I only had a knapsack and a change of shirts, a wool and gum blanket left. The next day I had to abandon my knapsack as the strap across my shoulders would stop circulation in my arms, so that I could not hold my gun. Form that time on I carried all my extra clothing, which was very little, rolled up in my blanket with the ends tied together and thrown over my shoulder. The battalion arrived at Huntsville, May 20th. I did my first foraging while on this trip. A few days after we left Clifton we camped one night a little before dark. So Jake and I went foraging. We were not allowed to take our guns outside camp. I had an old pepperbox revolver. We went out about a mile and found some young calves in a pasture. We got them in a fence corner and I bean shooting at one but couldn’t knock it down. Finally Jake caught it and we got a quarter of veal and struck for camp unmolested. May 22nd our brigade arrived. The battalion was then disbanded and its members sent to the company and regiment to which they belonged. Our (Crocker’s) brigade was then placed in the 17th army corps, that time commanded by Gen. Frank P. Blair. From that time until the war closed my postoffice address was Company C, 11th Iowa Infantry, 3rd Brigade, 4th Division, 17th Army Corps. Early in April 1864, General Sherman was at Chattanooga, Tennessee, when he received orders from his commander in chief, Gen Grant, then in command of the Army of the Potomac, to make immediate preparations for a campaign thru Georgia. Sherman at once set about the task. Rapidly gathering his soldier s from far and near all thru Kentucky and Tennessee. The veterans who had fought with Buell and Rosecrans the fall before, were scattered in small detachments protecting railroads and garrisoning forts. These were summoned to the front, together with the veteran troops that were home on furlough during the winter of 63-4. By the 6th of May these armies were assembled at their appointed places; Gen. Thomas at Ringold, Gen McPherson at Gordon’s Mill, Gen. Schofield at red Clay near the Georgia state line, a little north of Dalton. The combined force numbered about 98,000 men and 250 cannon.

P.29

The Confederate army of about 60,000 men, including a very superior force of cavalry, was also in three divisions under Generals Hardee, Hood and Polk. The whole force being under the supreme command of Gen. Joseph Johnston. They were strongly fortified in and around Dalton. The first object of the campaign was to secure Atlanta, one of the most important towns in Georgia. Here railroads from every direction centered. Immense manufactures of war materials were established here. The path to Atlanta lay thru Dalton. The country full of ravines, forests and interlacing rivers, was peculiarly adapted for defensive warfare. The army fighting on the defense always has greatly the advantage in selecting its position for battle. The roads from Ringold and Red Clay met at Dalton, a strongly fortified town. The Confederates had prepared to defend this place to the utmost. It was very essential to Sherman that it should be taken. The town is on the East Tennessee & Georgia railroad, one hundred miles northwest of Atlanta and thirty eight miles from Chattanooga.

On the morning of May 7th, Gen Sherman ordered the three divisions to move forward with center on Dalton. The reader will understand that these divisions moved forward on parallel roads, at times several miles apart. The country between these moving columns was covered by cavalry. When the rebel pickets were confronted they were driven back within their lines, oftimes (sic) with considerable loss of life. When the rebel works were found too strong for our forces to assault, without endangering great loss of life, Sherman would apply strategy, and order one of his generals commanding a division or corps to flank the works to right or left. The rebels would then fall back to another position and fortify it, if it was not already fortified. In this way the two armies fought over nearly every foot of ground several miles in width from Dalton to Atlanta. When Sherman was nearing Dalton, a small stream swollen by recent rains, was to be crossed about two miles west of the town, and the rebels had destroyed the bridge. Sherman, in his characteristic manner, asked the superintendent of a construction train “How long will it take to throw another bridge across that stream?” “It can be done in four days”, was the reply. “ I will give you forty-eight hors or a position in the front ranks be-

P. 30

fore the enemy.” It is said the bridge was finished in the specified time.

It is said the bridge was finished in the specified time by May 20th. Most of the 17th corps returned from furlough. General Sherman ordered Blair to leave Huntsville with his corps for the front. In connection with the corps Blair had a brigade of cavalry, a battery of eight guns, the ammunition wagons, ambulances, and a pioneer Corps assisted in making bridges, blazing the way through the timber, where there was no road, for the troops to follow. Throwing up fortifications and etc. we left Huntsville, crossing the Tennessee River at Decatur, and marched west and south of Chattanooga and Atlanta Railroad, arriving at Rome, Georgia May 5th. My diary says “ having marched 174 miles in 11 days”.

The Union General Jefferson C. Davis, whose patriotism redeemed the name had seized Rome on the 16th of May. There were many buildings there for the manufacture of articles of war. For the first time we were now within hearing of cannonading at Allatoona Pass about 20 miles away. From Rome, we proceeded to follow the railroad to Kingston where it connects with the Chattanooga and Atlanta road and down the railroad through Allatoona Pass and Ackworth too. Big Shanty Station near Kennesaw Mountain. Here we threw out our skirmish line and joined in line of battle to the right of the railroad. We advanced forward through heavy woods and underbrush. We had gone but a little over a mile until our picket line came to the rebel pickets. After some skirmishing with the rebels we were halted and threw up our breastworks. This was usually done by digging a trench about 2 feet wide and same depth in putting the dirt on logs and rails placed lengthwise along it. At this time our corps had joined Sherman’s main army and placed with the 15th corps which was known as the Department of Tennessee and commanded by Gen. George B. McPherson. Sherman’s main line now encircled Kennesaw Mountain extending from the railroad on the north to new Hope Church on the south about 15 miles. We continued driving the rebels back most every day until 14th of June when we got to within about a mile of the base of the mountain. Here we threw up strong fortifications and prepared for a siege. On June 17th, there was a general demonstration made along our lines; threatening a charge

P. 31

on the rebel works. The troops under General’s Thomas and Scofield that lay to our right charged and captured Lost Mountain with considerable loss. Our brigade did not leave the works. Our Captain Joseph Neil was slightly wounded in the shoulder by a rebel sharpshooter and several men in our regiment were wounded on a skirmish line. This was my first sight of a real battle June 20th our brigade was moved to the left across the road about a mile and took a position on little Kennesaw Mountain. Here we again threw up works. A few days afterward a battery was placed in position just behind our company and began shelling the rebel picket line. It had fired but a few times when a shell burst just as it came from the muzzle of the gun several pieces struck the head log of our works near where I was sitting and threw several splinters in my neck wounding a comrade who sat near me in the hand with a piece of the shell. At times our picket posts and the rebels were so close to avoid being killed or wounded, the sentinels were relieved at night. Imminent danger did not stop the comrades from playing pranks upon each other. One night six of us were detailed on picket when morning came we were in plain sight of the rebel post not over 300 yards distant. Before noon we got into a lively skirmish. Their bullets came thick and fast and often dangerously near while Comrade Flack, the oldest man in our company and others were busily engaged returning the fire, a mischievous comrade cut a bullet in small pieces and when a high musket ball whizzed close to Flack’s head, he threw the lead in Flack’s hair just back of the ear. Flack dropped his gun, threw up his hands and began hollering my God boys, I’m shot, I’m shot. Then all in the post had a hearty laugh.

On the night of July 2nd, the battery wheels were muffled by wrapping them with gunnysack and with our brigade we left the works at that point moving to the right in the rear of our mainline marching all night. When morning came, we could see the stars and stripes on Kennesaw Mountain the rebels evacuated it that night. We continued marching to the right occasionally skirmishing with rebel pickets that finally drove them back across Nick Ajack Creek the evening of the fifth of July. Colonel Hall, commending our brigade, wanted to charge

P. 32

the rebel works. Some of the officers of the brigade thought the works too strong to attack. Hall was riding up and down the line saying “The Iowa brigade could take hell.” A consultation of the officers commanding the regiment was held and it was decided to send an orderly and have General Giles A. Smith commanding the division, come and view the situation. In a short time he arrived and with the aid of field glasses viewed the rebel works on the opposite bank of the Creek. He finally ordered a battery up and it was placed in position near our regiment. A few shots were fired at an old cotton gin, that stood on the opposite side of the creek. We soon saw the “Johnnies” running from the building. The rebel bands were concealed behind their works. Soon one of their batteries opened fire on our gun, and the first shot tore a wheel off, wounding three men and killing one horse. Our battery was silenced. The charge was abandoned and we were ordered to throw up works. But little firing was done that night, or the next day, except on the picket line. Our batteries replaced on the hill on our rear. The next day they fired a shot occasionally at the rebels. About 5 o’clock in the evening, the rebel guns opened fire on our batteries and for about half an hour there was the liveliest cannonading that I heard during the war. A rebel’s shell shot through our works, near our company, until we could see the point between the rails. We lost no time in getting out of the works, although the shell did not explode, and no one was hurt. The rebels evacuated their works at night. The next day we moved forward, driving them across the Chattahoochee River. Our line was then established on one side the river and theirs on the other. For several days we put in the time exchanging shots. It was here that we learned to dodge a bullet, when fired from the opposite side of the river. Some may doubt this statement, but from experiments we made, I believe it possible, under right conditions, for one to dodge an old Army musket ball at a distance of 400 yards. Go with him to vote with the improved guns and smokeless powder, I wouldn’t advise anyone to try the experiment. July 17th our corps was ordered to move to the left of the entire army. At that time the entire rebel force had fallen back across the Chattahoochee. We took up our line of march in the rear of our mainline, passing through Marietta, near Kennesaw Mountain, and twenty-

P. 33

four miles from Atlanta. Marietta is one of the nicest little towns I saw in the South. We continued our march, crossing the Chattahoochee at Roswell, and camped for the night on Peachtree Creek. Next-day we passed through Decatur, a small town on the railroad six miles northeast of Atlanta. From here we moved south about 2 miles, where we formed in line of battle and our corps joining with the main line. We advanced a short distance, halted, and stacked arms for a little rest. We were eating blackberries when a rebel battery, secreted in a clump of trees at a short distance from us, opened a raking fire on our line, knocking our guns in every direction. We were “to arms” in a moment ready for action. The battery only fired one shot, then left. Here we threw up works and remained for the night. Most of our company was detailed on picket. We were close to the rebel picket line and made good stockades. About 3 a.m. July 21st, I was on duty and heard the rebel drum beating, and soon heard the command “fall in, forward march”. Every man on our post was up in a moment. We could plainly hear the marching. In a few moments the command “halt, stack arms” was given, and the sound of the ax relieved our fears. The rebels were strengthening their works by felling trees. All their forts and fortifications around the Atlanta were well protected in front, and by felling trees, massing the limbs and sharpening them. Sometimes logs with holes bored through and long pins driven in and sharpened, were used for abatis. When daylight came here, we could see two men chopping at a tree, about 400 yards distant. Brother Mifflin and I shot several times at them, but they continued chopping. Finally we’d doubled our cartridges and fired. When the smoke had cleared the way the tree was standing but the men were missing. That morning about sunrise Sergeant Moor of our company was coming from another post are to ours and when near our post was shot and mortally wounded. He died next day. When he fell brother Mifflin and Comrade Dodds of our company ran out and carried him into our post. A shower of rebel bullets came through the rails of the post as they ran in. About noon that day a charge on the rebel works was ordered. I had taken several canteens and gone to the rear to a little branch to fill them. When the charge was ordered our company deployed as skirmishers and went forward

P.34

but the regiment for some cause do not leave the works. The 13th Iowa charged across an open cornfield. It lost 90 men killed and wounded in about 20 minutes. Our company lost some wounded and missing. The rebels repulsed our men and they had to fall back to their lines. When the charge was ordered I was about halfway between our mainline and our picket line. I took shelter behind a small tree, lying close to the ground. Some shot and shell from the rebel guns threw dirt over my legs, but I came out without a scratch.

On the night of the 21st our brigade was relieved by other troops and we moved about a mile to the left and joined with other troops. Our brigade was then on the extreme left of Sherman’s line in front of Atlanta. The 16th Iowa being the last regiment with the 11th, next a battery of four guns placed in a road between the regiments. Here we threw up strong works. Morning came and everything was quiet in our front, scarcely was the sound of a gun heard. Some troops were sent out to reconnoiter in front. Brother Mifflin and Jake were with them bringing some green apples. We had cooked them and were eating dinner when we heard musketry firing in our rear. It increased very rapidly. In a few moments the command was given “fall in”. Soon the firing began on our picket line in front. In a very short time our pickets came running into the works. The firing was increasing in our rear. In a few moments we could see the rebel battle line coming out of the woods charging across an open cornfield in front of us. Then the command was given us “to move by the right flank double-quick”. That meant run to the right along our line of works. I started running and Comrade Stobber, in the file just ahead of me was shot from the rear and fell dead in the trench. I jumped over him and continued running. When I got to where the head of our company had been, Comrade Washburn and some others were sitting down with their backs to the works. Washburn said “Jennings lie down, you’ll get shot.” “I’m going while there is a chance” I said. He was taken prisoner and sent to Andersonville. We ran up the line of works two or three hundred yards, then were ordered over the works. From this position we could see the rebel troops closing in around the 16th Iowa.

p.35

Some of our men wanted to shoot, but the officers wouldn’t let them for fear of killing our own men. In a few moments we saw the rebel column coming out of the woods across an open cornfield toward us. Then the command was given retreat. Away we went pell-mell through the woods for about a quarter of a mile to another line of works. Here the officers were trying to reorganize their men, when General Smith, commanding the division rode up and ordered Colonel Belknap to try and recapture the 16th. “Who will lead the charge” asked Smith. “I will” said Captain Cadle of our regiment, and putting spurs to his horse jumped him over the works and withdrawing sward shouted. “come on boys”. With a yell and flags flying, amidst the roar of the cannon, the shrieking of the shells and the whizzing of the bullets, over the works after him we went. We charged through the woods about 200 yards when Cadle saw a rebel column moving rapidly to our left in rear. He halted and ordered us to fall back to the works. Captain Cadle was a brave young officer. At the time he was aide-de-camp to General Smith. At the Battle of Shiloh he had half of one ear shot off. The rebels came rapidly forward and charged our work several times, but were repulsed and driven back. During their last charge the color bearer and kernel of the 45th Mississippi got clear on our works. The colonel having his sword drawn was in the act of striking Belknap when he was shot to the shoulder by one of our men. He fell forward and Belknap caught him by the coat collar and drew him in the works when he surrendered. The pan is yet to be made that can truly tell of the bravery that triumphs over fear in men at such a time.

Several flags and 150 prisoners were taken by our brigade. Many of the man got so close to our works that they could not get away without danger of being killed, threw down their guns and surrendered. History says in substance, that on the night of July 21st, the Confederate Gen. Hood, quietly withdrew a large part of his army from in front of Atlanta, moved down to Sherman’s left wing, and about noon on the 22nd, surprised General Blair by making a desperate attack on the rear and front of Smith’s division, which was crushed back. Eight guns were taken and the 16th Iowa captured. Hood was finally driven back within his lines, having lost at least 2200 killed. His wounded

P.36

and missing swelling his loss to at least 8000. The 11th Iowa bore the brunt of the fight in Smith’s division. About the time the battle began, General McPherson ordered Logan, commanding the 15th corps, to move rapidly for ward and join his corps on the left of the 17th. Macpherson rode forward to see if the corps were joined, and when near the 16th Iowa corps, ran into the rebel pickets and was shot from his horse. When McPherson fell, Logan, the greatest volunteer soldier of the war, was placed in command of the Department of the Tennessee. I was detailed to help guard the prisoners, to the rear, that we had taken. We were just leaving the field when Logan came riding along our line, on his fine black horse covered with foam, far in advance of his aides, holding his hat and rein with one hand, and waving his sword is the other, urging the men, at the top of his voice to stand firm to the works and avenge McPherson. We had proceeded but a short distance with our prisoners when we overtook the other prisoners, under guard. Among them was a rebel captain that had on General McPherson’s hat. Soon afterwards an ambulance containing the body of McPherson, with some of his staff officers guarding it, came along. One of the officers noticing McPherson’s hat on the rebel captain, rushed his horse in among the prisoners and grabbed the hat off his head, at the same time using language not fit to be heard in Sunday school. We continued our march with the prisoners to the rear until near Decatur, where we camp for the night. Next morning I was relieved and returned for my regiment, then on the battle line, near where I left it. On my way back I stopped at our field hospital, for there were many dead and wounded. The Army surgeons were busy caring for the wounded. They had arranged temporary tables, made out of rough boards, on which wounded were placed to amputate their links. At the end of those tables I saw piles of legs and arms two to three feet high. Arriving at my company I found brother Mifflin and my friend Jake, Mifflin was wounded in the hand the day before, with the end of his ramrod, while trying to dislodge a bullet fast in his gun. Nearby the company lay two of our company who were killed the day before, not yet buried. From my diary I quoted the casualties of our company, on the 21st and 22nd of July: “Killed, eight, in-

P. 37

cluding two orderly sergeants; one lieutenant, and Captain Neil. Wounded and missing nineteen.”

The 16th Iowa were mostly taken prisoners early in the flight on the 22nd, by General Govan, commanding a division in the rebel General Hardy’s corps. They were exchanged shortly afterward and returned to our brigade. When surrounded by the rebels, Colonel Saunders, commanding the 16th, surrendered the regiment, with its flag, to Govan, who afterward sent the flag to his sweetheart at Little Rock, Arkansas. In the fall of 1884, our brigade held a reunion at Cedar Rapids, Iowa. General Beltnap, President of the Association, and invited Gen. Govan to attend the reunion, which he did. The second night of our campfire, held in a large opera house, before a large audience, Govan in a nice little speech, delivered the regimental flag of the 16th, back to Colonel Saunders from whom he took 20 years before. I was present at the time. It was a scene long to be remembered.

July 26th our brigade and corps left their works and marching in the rear and to the right of the main line, coming in and forming on the extreme right of the whole army near Ezra Chapel about six miles southwest of Atlanta. While our lines were being established here the rebels attacked the 13th Iowa, killing one man and wounding three.

Here we threw up strong works and remained about two weeks. No general advance was made by either side. We were daily under fire in the main works from rebel sharpshooters, with a gentle reminder every few hours that we were within range of a very large gun in a rebel fort near Atlanta. The large balls would come whizzing through the woods, occasionally knocking the lambs off trees. We could hear them coming a mile away. Brother Mifflin and I were both quite unwell but remained with the company until the 14th of August. Then we were sent to the division hospital, established in the field. We remained there but a short time when we were loaded in wagons with other sick and went back to Marietta, to the General Hospital, which was established in a college building. Mifflin remained at the hospital until the eighth of September. I stayed until the 15th. On returning to my company I founded in camp about 4 miles southeast of Atlanta. While I was in the hospital Sherman wasP. 38

constantly tightening his lines around Atlanta and destroying roads on which it depended for supplies.

The Confederate General Hood, sought to avert the final blow by sending Wheeler’s cavalry to operate in Sherman’s rear. But Sherman sent General Kilpatrick with his cavalry, at once, to break up the West Point and Macon railroad. Then he abandoned the siege of Atlanta, and sending his sick with the surplus wagons to the Chattahoochee, he put his whole army in motion, and before Hood penetrated his design, he was behind Atlanta, destroying the railroads on which Hood depended. That General now divided his Army. Hardy with one portion advanced to Jonesboro. Here on the 31st of August, he came upon General Howard, with the 15th and 17th corps, Howard was strongly entrenched behind works, and calmly awaited attack. It was made with great courage and skill, but after two hours of terrible struggle, Hardy retreated leaving his dead and wounded. Sherman then came up with Thomas and Schofield, who had been breaking up the railroads, and by a vigorous attack carried Confederate lines at Jonesboro, capturing General Govan, who captured the 16th Iowa, July 22nd, with his brigade and batteries. Hardy retreated in haste. Hood, cut off from all supplies, with his army scattered and beaten, blew up his magazines, destroyed his stores, evacuated Atlanta and fled on the night of August 31st.

General Sherman, with the brilliant cavalcade entered the city. The stars and stripes were unfurled from every spire and over every rampart. He telegraphed to Washington “Atlanta is ours and fairly won”. Without making any attempt to pursue and capture any of the scattered divisions of Hood’s Army. Sherman concentrated his whole force at Atlanta.

While Hood’s cavalry was riding into Tennessee, Hardy had affected a junction with Hood near Jonesboro, and the defeated army was reinforced, and visited by Jefferson Davis, who sought to arouse the enthusiasm of the rebel soldiers in the gloomy days that had befallen them. He urged that Atlanta should be retaken. Hood then crossed the Chattahoochee River about 25 mile below Atlanta and came in on the railroad near Big Shanty station and commenced tearing it up. In the meantime, General Sherman dispatched General Thomas with the 20th corps to Nashville, to check any Confederate movements in that state,

P. 39

and now he started in pursuit of Hood. On the morning of October 4th our corps took up the line of march for Marietta. The day was very warm. It rained the night before and the roads were very muddy. As we had done but little marching for over a month, the men and teams were in no condition for a forced march. But everything was on the rush that day. I saw many horses and mules give out. They would drop in the road, their harness was removed and were left lying alive, for other teams and wagons to run over. We got within about 4 miles of Marietta and stopped for camp, with but few men in the company to stack arms. I could not keep up with the company, but got to camp about an hour after the first troops did. The next day our brigade made a tour south about 15 miles and camped near Powder Springs I was on picket that night. An amusing incident occurred about one o’clock, that I will never forget. I thought I heard a man walking in the leaves through the timber. My first thought was a rebel picket advancing. Soon I heard the comrade on post next to me calling halt, at the same time the sharp crack of a gun sounded, an old hound dog went yelling through the woods. I quit shaking then. The next day we returned to Marietta, over much of the road we traveled the day before. We marched about two miles beyond Marietta and found our division in camp. The next day our brigade lay in camp. I was sent out with the party of foragers. We had got about 10 miles from Camp, but found little to eat, when a messenger came from Camp with orders for us to return at once, as our brigade had orders to move. So we returned. At eight o’clock that night we left camp, following the railroad, leading to Big Shanty Station. We passed Big Shanty during the night and when morning came we were nearing Ackworth Station. Here the rebels had burned several carloads of our cattle. When near Ackworth we could hear heavy cannonading at Altoona Pass, for Gen. Corse was being attacked by the rebels. About this time General Sherman was on Kenesaw Mountain signaling to Corse those memorable words that have gone into sacred stone to “Hold the fort for I am coming.” Corse held the fort, and defeated the rebels, with heavy loss. Our brigade was pushed rapidly forward passing through Allatoona about two o’clock in the afternoon.

P.40Here we saw many dead and wounded rebel soldiers lying around in front of the fort and breastworks.

We continued our march to Kingston. Here we stopped for a few hours and got mail, the first we had received for over two months. Brother Mifflin received a letter from home giving the sad news of the death of our mother. We did not know that she was sick. From here we marched parallel with the railroad leading to Rome. When within about six miles of Rome we camped at 1:00 a.m. Our camp was on the farm of the Confederate General Pemberton, who surrendered to Grant at Vicksburg. We lay in camp that day until about eight o’clock that night when our brigade was ordered to Resaca. The rebels had made an attack there and our troops were needing reinforcements. General Belknap and his staff, leaving their horses and securing an old colored man for a guide, started marching through the woods and over the hills, until we reached Millwood, a station on the Chattanooga and Atlanta railroad. Here we were put on stock cars and run about 20 miles, reaching Resaca about daylight. That night I expected our train would be ditched, as there were no guards along the road. I was on top the car, and fearing that I might go to sleep and slide off, I fastened my gun strap to the run board on top the car, then tied it to my wrist. The next day our corps came up. We stayed there two days. Leaving Resaca we moved west a few miles and met the rear guard of Hood’s army, well fortified at Snake Creek gap, a narrow passage to the mountains. The rebels had felled trees across a road for several miles that took our troops all day to remove. There were several rebels killed and wounded near the mouth of the gap. The leaves in the woods took fire and I saw several rebels, with their clothing all burned off but their shoes. We continued our pursuit of Hood’s army, until we reached Galesville Alabama, October 26th. This was as far north as Sherman followed Hood. Here our non-veterans, whose time had been out for over a month, left for home. On October 29th, we started on our return, going by way of Rome, fans to near Marietta, for we went into camp, having marched much of the same country over three times during the summer.

Since leaving Huntsville in May, our brigade had been on the march or in the rifle pits most of the time from the 14th of

P.41

June to the first of September. There was scarcely a day during that time that we were not under fire of rebel bullets many of our comrades were killed and wounded during this time of which I have no account. While in camp at Marietta we were paid off, the first time in three months.

It was here that I cast my first vote, in my 20th year, for Abraham Lincoln for president. The laws of Iowa at that time, permitted all soldiers to vote, regardless of age. Here I was detailed his provost guard at General Belknap’s headquarters. After that I had nothing to carry when on the march but my gun. I left my company and was not with it, for duty, any more during the war. While serving as provost guard I took my turn guarding brigade headquarters when in camp, and at night while on the march; also had to carry ammunition in case of battle and help carry the wounded from the field. Before leaving Atlanta, Sherman withdrew all his men stationed along the rail road leading to to Chattanooga and from the roads entering Atlanta, and destroyed the roads. The most effectual method of destroying a railroad was to burn the bridges, pry the iron rails loose from the ties, piled with ties and large heaps and set them on fire, then place the rails across the fire near the center, when the iron was red hot the rails would bend olong you are not out yet that what every three or so are a youth is he in his youth and that the matter is that I read r being and will work well on ist out of shape. Sometimes the real got red hot the center to me and would grant each and then run around a large tree in Sabeans meant I’ve seen rails piled up in this way until the tree was burned down.

General Sherman now had under his immediate command the 15th, 16th, 17th, and 23rd corps, comprising about 60,000 man and some 200 pieces of artillery with the regular ammunition and supply trucks. These Corps traveled on parallel roads, as near as possible, about 15 miles apart. The cavalry and foragers covering the country between them. On the morning of November 13, Sherman ordered a general move and we started for the “sea”. About the time the troops began their march all the public property in Atlanta, Rome, Kingston and Marietta, such as arsenals and factories which could serve the rebel armies were consigned to the flames. On this March we met but little opposition, mostly home guards in state militia until we got near Savannah. While on the march our boys lived well ----sweet potatoes and chickens were ripe. Our Corps

P 42

passed through Milledgeville, the capital of the state. I quote from my diary December 6, ‘64: . Near here our advanced guard encountered a heavy rebel picket line that detained us for some time. We camped near Oliver Station on the Savanna and Atlanta railroad, 40 miles from Savanna. General Sherman’s headquarters are about 100 yards from ours”. As we drew near of the doomed metropolis our march was impeded by a shameful and cowardly mode of warfare, introduced by the rebels and worthy only of Savages. Torpedoes were buried in the road near all springs of water, which exploded beneath the pressure of the foot scattered mutilation and death around. Many soldiers were killed and wounded in this infamous way. General Sherman adopted the severe but just precaution of compelling the rebel prisoners of war to go in advance and remove the deathtraps

We continued to press forward slowly until our advance m met a strong rebel force, well fortified behind breastworks near Fort McAllister, which stood near the mouth of the Ogeehee River. The Confederate guns and the forks could prevent our boats coming up the river with supplies, which we were very much in need of. Sherman now established his mainline from Fort McAllister, extending north to the Savanna River, and about 3 miles from the city. November 13th, just one month from the time we left Atlanta, Hazen’s invasion of the 15th corps in a brilliant charge, captured Fort McAllister, with several guns and a large number of prisoners. Our boats with supplies failed to arrive for several days. We were out of rations for nearly a week, had little or nothing to eat, except rice in the sheaf, bound in bundles, like oats. We had to pound the berries out with our bayonets. In the meantime we had a few ears of corn to eat. I remember standing guard over our horses while they eat their corn to prevent the Negroes, who had followed us from getting it. Sherman continued to close in his lines around Savanna. General Hardee, then in command of the Confederate forces in Savanna, seeing that further resistance was hopeless and that his army was in danger of being surrounded evacuated the city on the night of the 24th, crossed the Savanna River with his army, into South Carolina. Christmas day, General Sherman, riding at the head of his triumphant columns rode through the broad, quiet avenues of Savanna. On the 26th Sherman sent the

P. 43

following telegram to President Lincoln: “I beg to present to you as a Christmas gift, the city of Savanna, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, also about 25,000 bales of cotton.” Thus, Sherman’s army had swept the state of Georgia from “Atlanta to the sea” for a width of 60 miles and history says “with no loss of life, but that of 63 men killed and 245 wounded.” The main part of Sherman’s army remained in Savanna about a month. About the 25th of January ‘65, the 17th corps was sent to Beaufort South Carolina to seize a point of the Charleston railroad near Pocotaligo Creek. Our brigade was sent by boat down the Savanna River and around on the Atlantic to Beaufort. The voyage was very rough. Most all our boys grudgingly gave up their hidden rations, but freely pitched them overboard to the fish and alligators. Sherman left Savanna with his main force about the first of February, heading for Columbia South Carolina. About the same time our corps left Beaufort. We encountered the rebel forces at Pocotaligo Creek, where they made a stubborn resistance, but were finally routed. We had several wounded in our brigade and one captain in the 15th Iowa killed. Near here I was appointed orderly for Captain Kepler, an aide on General Belknap’s staff. Then I had a better horse to ride. It was my duty to carry any orders that Kepler wanted to send to any other officer of the brigade and while on the march to care for his horse when he left it. When in camp a colored man cared for the horses. A short time after I was appointed orderly, or foragers brought in a little iron gray pony, with shaved mane and tail, that they found shut in a corn crip, to hide it. I got the pony and wrote up from there to Washington, D.C. Our army traveled through the Carolinas in about the same positions as through Georgia. Leaving Pocotaligo our corps push slowly forward through miry swamps and muddy roads, some days not marching more than five or six miles. Our next encounter with the rebels was at Saltkahatchie Swamp. This swamp in many places is over a mile wide and covered with small timber and heavy underbrush, with water running all through it from six inches to four feet deep. At the point where we struck it, it is so miry that horse cannot pass through it only on the made road, and it’s almost impassable for a man. We found the rebels strongly entrenched on the opposite side of the swamp, having

P. 44

placed a sentry in position to make a raking fire on the road. Our battery was soon placed in position and began shelling the rebel works. The firing was kept up most all day. In the meantime our officers were hunting for an opening through the swamp, where they might effect a crossing. Finally an old colored man was found, who told them that there was a path through the swamp about 2 miles below where we were, that people sometimes crossed on foot. Our brigade was selected to make the effort to cross the swamps. Leaving everything behind but the man and guns and ammunition. Our brigade led by General Belknap and his staff and the old colored man marched down the swamp to the place where the path led through. The men placing their cartridge boxes around their shoulders, then preceded to wade. After several hours of hard struggling we reached the opposite side, wet to the hide, from our shoulders to our feet. At once our picket line was thrown out and the brigade formed in a half circle, each end resting on the swamp; then we threw up works. We had been there but a short time when the rebel cavalry attacked our pickets. But they were soon repulsed.

We built fires and dried our clothing as best they could, and remained there for the night. When morning came the rebels had evacuated their fort at the road crossing the swamp, and none were to be seen. Our boys found an old white mule and saddle and tied some chickens to it, and General Belknap rode it to our command. While on our way back to the command, Jake and I made a little detour, trying to find something to eat. We came to a log cabin with a smoke house nearby. And looking through the smokehouse we found some honey and some flour in a barrel, but we couldn’t find anything to carry the flour in. Finally Jake said let’s go to the house. You talk to the women and I’ll try and find something to carry the flour in. At the house we found an old white woman in two grown girls. I entered into conversation with them asking them where their men folks were? They replied, “away at Richmond in the Army” I asked how far it was to Richmond. They said they didn’t know. I asked how far it was to the United States. They replied as they had never heard of it before, that it must be a long ways. In a short time, Jake pulled out a bureau drawer and got hold of one of the girls extra shirts, and was

P.45

just in the act of putting it under his shirt when one of the girls saw him. She grabbed the shirt got hold at one end and Jake the other, then she commenced begging. She said “it was the last one she had”. She pulled and Jake pulled. Then I began to wilt and finally said to Jake that “I wouldn’t take it”, but Jake said “God ding it, we got to have something to carry the flour in common” and jerked it out both the girl’s hand. We tied a string around the top, took some flour and honey to camp and had “slapjacks” for dinner. I know that was the meanest thing Jake and I ever engaged in while in the Army. I have often wished sense that I knew that girls address; I would gladly send her a dollar. Whenever I tell that story on Jake and he is present, he tries to even up with me by telling that I kept the garment. I never was very good at foraging. But my friend Jake was considered one of the best foragers in our regiment. If there was anything in the country to eat he could find it. I believe the nearest I came to being captured was on our march through Georgia. One day I went out with some foragers and rode an old white mule. Soon after leaving camp I found a rebel cavalry man’s Navy revolver and belt lying in the road. There were no cartridges in the gun. I buckled it on and rode ahead. During the day we captured an old mule cart, and secured a fine lot of forage, consisting principally of sugar, sweet potatoes, flour, meal, chickens, ham and bacon. On our way to camp, while passing a house I saw a girl at a window crying. I rode through the yard gate around back of the house and dismounted. Entering the house I found two of our man carrying up things generally. They left at once. I went in the room where the girl was crying. Here I found her mother crying, both badly frightened. I was talking with them win one of our men rode up in seeing me called out. “The rebels are coming.” I lost no time getting out. Mounting my mule I rode round the house, where I saw several rebel cavalrymen coming down the road not over 400 yards away. I had no gun, only the one I found that morning. Heading my mule down the road toward camp, I turned about half way round, and while watching the move of the rebels applied begun on the mule, and finally made my way safely within our lines. Leaving Saltkahatshie and pushing our way slowly north, with but little opposition, we reached the West Bank of the Congaree

P.46

River, opposite Colombia, the 16th day of February, 1865. Here we found a bridge across the river burned. General Logan, commanding the 15th core, was in advance. It was said of him that when he rode up to the river and saw the Bridge was burned he said, “Hail Columbia, happy land. If you don’t burn then I’ll be d__.” The Salusa and Broad rivers for a Junction near Columbia; then it is called the Congaree. Sherman’s next move was to affect the crossing of the river. Wade Hampton, Confederate general, was still in Columbia, holding the city with a body of cavalry. Late in the evening of the 16th, Logan affected our crossing of the Saluda river. Jake and I went over among the first of Logan’s man. We went to a house that was about a quarter of a mile from where we crossed the river. In the front yard lay a rebel cavalryman’s horse with saddle and bridle on it; it had been killed by Logan’s advanced skirmishers.

That night Hampton evacuated Colombia, leaving a strong guard in his rear. At the time we arrived our batteries were placed in position and began shelling the city. An old mill stood on the opposite bank of the river, in which some rebel guards were placed. The shots from our guns were directed on the mill. In a short time the rebels were seen skedaddling from the mill. When the morning of the 17th came, some 20 men and three officers of our brigade were detailed to try and effect a crossing of the river. Securing an old leaky ferryboat and after considerable caulking, the party started across the river under cover of the old Mill, while our batteries kept firing their guns over the mill into the city. The boat was safely landed and the men deployed as skirmishers to await reinforcements. The boat was safely landed and another detail made. I got permission to go with them. We were soon in the boat, dipping water to keep it from sinking while crossing the river. On landing our company was deployed as skirmishers and joined the other squad. Then all started for the State house. In the meantime, the rebel rearguard was leaving the city, some seem being seen by us at a distance. Reaching the Statehouse, one of our officers ascended to the roof and took down the Confederate flag and put up the stars and stripes. History gives a Crocker Iowa Brigade credit of being the first Union troops to enter Colombia. I

P. 47

went through the Capitol building, hunting what I might find. On the second floor I noticed in a room at table with some drawers. Pulling out one of the drawers I found about a hundred medical medals about the size of a silver dollar. On one side are the letters state agricultural Society at South Carolina. Also a cut of the Palmetto tree, a beehive, sheaf of rice, plow, spade, hand rake and sickle. On the other side are the letters “animus opibusque, Pasrati, Dum Spiro Spere.” I presume these were used for prizes in their agricultural society. I took one and afterword had my name, company and regiment and the date I got it, inscribed on it. I still carry it as a war relic. It is my desire that when I’m through with this relic, to have it and the Maryland dollar that my uncle Henry gave me, placed in the State historical Society of Nebraska. In the afternoon of the 17th, our corps moved from north of the city, crossed the river and entered the city with other troops. At that time there was a loud large amount of cotton stored in Columbia, which the rebel rearguard set fire when they were leaving the city. There was a strong wind and the fire spread rapidly, burning a large part of the city, and the Union army with blame for it by the Southern people. But in th suit years afterwards, before the British claims commission, held at Washington, D. C., it was proved that the rebels fired the cotton. It has been well said that “no other state or section, has in modern times, been so thoroughly devastated in a single campaign, signalized by as little fighting as was South Carolina by Sherman’s march..”

The day we left Columbia, our captain (Clark) had charge of a forging squad, and when a few miles from the city, he was captured by the rebels. We did not see him again until we got to Louisville, Kentucky on our way home. Foraging was a dangerous business in South Carolina. Many of our men were horribly murdered. The Southern people were very ingenious in burying their treasures. Our bummers were equally as shrewd in finding them. At Camden, near Columbia, our bummers unearthed in a newly made grave, a coffin containing $6,000 in specie. I remember seeing two newly made graves near Rome, Georgia with the name, company and regiment of two rebels and Kurd marked on the board. Our boys unearthed these graves and found boxes containing Amsden bacon. A very common place

p. 48

of hiding valuables was under the floor of Negro shanties and smoke houses. I have seen boxes taken from under such force containing all kinds of glass, China and silverware and cutlery. I now have a silver teaspoon which I picked up off the floor of a Negro Shanty near Beaufort, S. C.

Household goods were frequently hit in the timber or in the swamps. I recall while riding along the road one day near a swamp of noticing a widening track leading into the swamp. Another orderly and I followed the track, riding through the swamp, at times with water to the horses bellies. Some five or 600 yards we came to a large pile of household goods on the little mole. Some “bummer” had been there and set them on fire. I never did such work as that.

On the morning of the 18th our corps left Columbia, with the third brigade in advance. We traveled nearly due east, crossing the Catawhbwa River about 18 miles from Columbia. Shortly after crossing the river we came to three fine empty carriages just standing at the side of the road in the timber. We marched about 2 miles farther and camped near a road crossing, where there was a blacksmith shop, post office and two large plantations nearby, with fine large buildings. General Belknap made his headquarters at one of these houses. At this house there were 10 or a dozen women who had recently occupied the empty carriages we had passed. I suppose they were the elite of Columbia. Thinking to avoid Sherman’ s army, they had taken this route and were overtaken by the rebels, who took their horses. The next morning when our troops were moving out from camp, General Belknap told me to stay and guard the premises until all our men had gone. The women were very friendly to me. No doubt they thought as long as I remained they would not be threatened by our soldiers. I stayed until nearly noon. They wanted me to stay longer. But I was afraid I might be overtaken by the rebels and adjudged a forager, and that often meant death in South Carolina. About this time a correspondent of the New York Herald wrote, “On the line of our march we found eighteen of our foragers murdered. Seven of them were placed in a row, side by side, with a piece of paper panned to the closing of each, upon which was written in pencil this is the way we treat Kilpatrick’s thieves.” Others were found

P. 49

By the roadside with their throats cut from ear to ear. Placed to these was a placard upon which was written, “South Carolina’s greeting to Yankee Vandals.”

It was a rainy day and the roads very muddy. I did not reach camp until dark. I had just got in and was caring for my horse when I heard General Belknap call “Sergeant Wilkinson.” he had charge of provost guards, “has Jennings got in yet.” “No,” the sergeant replied. “When he comes, tell him to come up here.” said the general. Then I called out, “I’m here.” I went to headquarters. The general was sitting by a pine knot fire in front of his tant. With a twinkle in his eye, he said “Where the devil have you been all day?” I replied that I’d stayed at the house where he left me in the morning until nearly noon, and the women wanted me to stay longer. “Well, why the devil didn’t you stay? It was a good place to stay, was it not?” he said.”That’s all right, Jennings. I just wanted to know you had gotten in.” This shows the general was interested in the welfare of his man.

Our command was now moving toward Raleigh, North Carolina. For many days there was incessant rain, streams were swollen, bridges swept away, greatly impeding our progress. After many days of tireless marching the 17th Corps arrived in Cheraw on the third day of March. The rebels retreated again across Pedee River, burning the bridge behind them. After destroying the military stores found here, we took up the march for Fayetteville, N. C. Where we arrived March 11th. Here we destroyed a vast amount of machinery which the rebels had stolen from the United States arsenal, at Harpers Ferry. At that time the Confederate General, Joe Johnston, was concentrating all his forces at Raleigh. On the 15th our corps moved out of Fayetteville, crossing the Cape Fear River. While our battery was the crossing the pontoon bridge here, an unusual accident occurred. For safety on the bridges, guns were kept quite a distance apart. A gun drawn by four horses was driven on the bridge and stopped near the river bank, which is very steep. Then a wagon loaded with pioneer tools and drawn by six mules was driven down the bank, the gun still standing. There not being room for the mules, the force of the wagon pushed them off the bridge, drowning the whole outfit, except the driver.

P. 50

On April 12 about noon, while we were marching for Raleigh, we received the glad news that Gen. Lee had surrendered his entire army to Gen. Grant. On receipt of this news there was an exciting time among our soldiers. Regimental flags and banners were waved in hats thrown in the air, while cheer after cheer was given. On the morning of the 14th our brigade entered Raleigh. As the Union troops drew near the city, Gen. Johnston, with his army, retired, and a deputation of citizens came out to meet Gen. Sherman and tendered him the surrender of the city without firing a hostile shot, and the Union troops marching to the tap of the drum, entered the capital of North Carolina. Raleigh was a beautiful city and suffered far less than any other place our troops occupied during the war.

The Confederate Gen. Johnston retreated to Bentonville some 10 miles distant, and here threw up a strong line of works. Sherman scarcely halting at Raleigh, moved his men forward in and our guard was soon attacking the rebels. They were promptly driven back to Bentonville, where our troops encountered a dismal swamp, with the rebels entrenched behind strong works on the other side. Our line was halted in order to throw up works. Our brigade headquarters was established about a quarter of a mile in the rear of the brigade.

The next day about one o’clock in the afternoon, heavy firing commenced along one picket line. As soon as the firing was heard at headquarters Gen. Belknap ordered his horse, and taking me as his orderly, we rode rapidly to our lines. Arriving there the general ordered the brigade to move forward, in the line of battle, at once, through the swamp, and dismounting his horse, left me to hold it. The brigade had advanced but a short distance, when the rebel bullets came flying past me thick and fast. In a short time a soldier came back and told me that the general said for me to move the horses over the ill out of range of the bullets. I felt somewhat relieved, then, and moved at once. The rebels were driven out of Bentonville without any loss to our company. That was our last battle and I have the distinction, if any, as serving as orderly for Gen. Belknap in our last engagement.

A few days later and armistice between Sherman and Johnston was agreed upon and on the 26th day of April 1865, John-

P. 51

ston made a final surrender of his army to Sherman. Lee having made a final surrender a short time before, the war was practically over. Pending the armistice between Sherman and Johnston, we received the sad news of the assassination of our loved and lamented President Lincoln; this caused a deep gloom to fall on all our troops. Many threats were made by the soldiers, that if the war continued, no prisoners would be taken alive. The soldiers generally believed that the main leaders in the rebellion had some knowledge of Lincoln’s assassination.

The war being over, the most important matter demanding the attention of the government was to lessen the expense by reducing the number of soldiers in the field. On the last day of April, Gen. Sherman with the 14th 15th 17th and 23rd corps which had marched with him from Atlanta through Georgia and the Carolinas to Raleigh, set out for Washington D. C. The corps marching on parallel roads in much the same position they did on the campaign. It was always a mystery to me, and many other soldiers, why the march was made so rapidly, unless it was rivalry among the corps officers to see which could out March the other. The Corps generally made from 20 to 25 miles a day. April 29 our corps left camp near Bentonville, marched about 10 miles, crossing the Neuse River to the east side and camped over Sunday. Monday morning, May 2nd, we started on the March for Washington. On the way we crossed over several battle fields in Virginia, where we saw the bones of legs and arms of the dead, protruding from the ground. There was an offensive odor from the field. On the march we had strict orders not to forage, and guards replaced at all houses near where we camped. One day we camped a little before sunset. I rode out about a mile from camp and came to a house where a guard was stationed. I rode along the road past the house some distance, then returned to camp. I noticed in passing the House some old-fashioned bee gums, made out of hollow linn logs sitting along an old rail fence, just back of the house, on the bank of a ravine. The thought struck me that there was a good chance to get some honey. When it became dark I got two of the boys in camp and we went out to the place where I had seen the bee gums. Arriving at or near the house we followed the ravine to keep outside of the guard,

P. 52

in front of the house, until we came to the bee gums. Then one of the boys and I climbed over the fence and grabbed up one of the gums and set it on the top rail of fans, when suddenly the rail broke and jarred the bees, so they fell down on our hands, and began stinging us, but we held onto the gum and climbed over the fence and carried it quite a ways down the ravine, then took what honey we wanted and returned to camp. My hands were severely stung and greatly swollen. The next day while riding along Gen. Beltnap happened to notice my hands and then he said, “ Jennings what’s the matter with your hands?” I replied that “by some means I got them poisoned last night.” “Yes” he said, “I think I know the kind of poison vine you were in.”Passing through Richmond, Virginia, we saw many of the old forts and strong lines of rebel works behind which Lee’s army had been sheltered for four years. May 21st we arrived on the hills of the Potomac, south of and near Alexandria, Virginia, about 8 miles from Washington and camped. The next day the soldiers in camp rested from their long march northward. All were busy cleaning their rifles, polishing their gun barrels and copper disk, and putting a fresh look upon their accoutrements preparatory to a grand review as a whole army. That day General Belknap and staff went to Washington. Going to Alexandria to take the boat, we passed a hotel where Col. Ellsworth, the first man killed in war, was shot while taking a rebel flag from the building and placing the stars and stripes in its place. We loaded our horses on the boat and went to Washington; spent most of the day there and returned to camp at night. Early on the morning of the 24th the 17th corps was on the march to Washington, the fourth division leading with our brigade in advance. The long wooden bridge across the Potomac was reached about 10:00 a.m.

In crossing the bridge we had to break step in keeping groups some distance apart, for fear the oscillation would cause it to collapse. From the bridge the call marched east around the Capitol building, entering Pennsylvania Avenue. To form a uniform rank of 40 men, the regiments were organized in equal companies, in double ranks, close order. When each command was ready, at the order, march forward. Fixed bayonets sliced in the sunlight from

P.53

the parallel lines of rifles obliquely held from right shoulders. From the Capitol to the White House, fully a mile, the line of march was visible in all its impressiveness. Great flags waved across the street, and along the sidewalk; the spectators, thousands upon thousands, stood gazing as if spellbound. Horsemen rode along the curb to keep people from breaking over into the space required for moving columns. There was no lack of patriotism. Mottoes, banners and flags were in great profusion upon buildings, private and public. From every window and housetop flags and handkerchiefs were waved, and hands were clapped. In front of the White House had been erected a platform upon which Andrew Johnson, then President, Generals Grant and Sherman, and many other noted generals, together with many state officials and governors of Northern states, reviewed the marching host. How this scene would’ve been heightened at Abraham Lincoln (who was assassinated a short time before) had stood looking with friendly countenance down upon “his boys.” This was our grand and final parade. I was riding with General Belknap staff at the head of a column, and looking back down Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House to the capital, over that gallant body of soldiers, marching to the Of the drum, was a site never to be forgotten.

We marched down about 7 miles north of Washington and camped in the edges Maryland, awaiting transportation. I made several trips to Washington, taking in the sights of the city. One day a comrade and I rode down to the capital. There being no hitch racks to tie our horses, we left them with boys to hold while we took in the Capitol building and grounds. We were gone perhaps an hour. When we got back my pony was gone. I found the boy I left it with, holding another Moore’s “where’s my pony,” I asked. “Why you got him didn’t you,” he said. “A man gave me $.10 and said that was his pony.” “Which way did the man go?” I asked. “Right up Pennsylvania Avenue,” he said. I took my comrade’s horse and rode up the avenue two blocks, then turned up an alley to a livery barn. When I rode up, there was a soldier bringing a horse out of the barn that had been stolen in the same way mine was. An old colored man sitting by the barn when I rode up, said, “I expect this man am hunting for a hoss too?” “That’s what I am,”

P. 55

I said. “What color was your hoss?” I described my pony “Well sah, I saw a man riding that pony through that alley (pointing to it) just a while ago, he said. I rode up the alley, crossing the next block to the street, got off the horse and examined the space between the buildings along the sidewalk.

In a short time I noticed horse tracks between two buildings that stood close together. I followed the tracks to the rear of the buildings. There under a shed I found my pony with saddle and bridle on the ground nearby, but no one to be seen. I lost no time in getting the pony out and back camp we went. Many horses were stolen that way. Gen. Belknap offered me the pony if I would pay the freight on him home, but that would’ve been more than he was worth. On June 7th our corps left Washington over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, in stock and grain cars, for Parkersburg, Virginia. Here we took boats for Louisville, Kentucky. There were seven boats in the fleet. They frequently got to racing, which would cause much excitement among the soldiers on board. When about 50 miles above Cincinnati, the boat carrying our Regiment struck a snag and sank in a few moments to the top deck. Many of the soldiers jumped overboard. The boat got near shore and all were rescued. When the accident occurred Mifflin was on lower deck. He grabbed his gun and ran to the upper deck but lost these baggage. I was on another boat was brigade headquarters when the accident occurred. Our fleet arrived at Louisville on the 14th of June we remain to hear a waiting discharge and transportation and till the 16th of July. Mifflin obtained a furlough and went home and did not return. On the fourth day of July our brigade was formed in a hollow square. Then Gen. Sherman rode in and made us a farewell speech. I shall never forget one statement he made. It expresses my idea of a true American. He paid a high compliment to the men of the brigade for their daring deeds of bravery and loyalty to him. And after recounting some of the great battles in which the brigade had been engaged and the dangers through which they passed, he said “boys I want to tell you one thing, I never sent you anywhere I would not have gone myself if duty required.” When the General rode away cheer after cheer was given him. While here Jake and I went down to the city and bought us new hats and

Picture of Jake and W. H.

P.56and had our pictures taken together. Later on I will tell about Jake’s short memory.

While here I came near being drowned. One evening several of us boys went swimming in the Ohio River. We entered this stream several hundred yards above a high bluff where the banks were very steep. The water was deep and the current was very swift. I swam out about 100 yards, then turned back. The current being swift carried me downstream show that when I reached the bank judiciaries keep. I was nearly exhausted and just floating downstream when fortunately I caught some pressure overhanging the bank and got out. We were discharged on the 15th of July. The next day our brigade crossed the rumor on a ferry boat to Jeffersonville, Indiana. Here we were put in box cars and taken to Chicago. There we were transferred to the Rock Island Road and taken to Davenport, Iowa, and again placed in Camp McClellan. In a few days we were paid off and mustered out of the service. Comrade Ashford and I went down to Davenport, and each bot a suit of clothes. As I now remember, we paid $40 a piece for the suits. The train had gone to Muscatine, so we had to stay in the city overnight. We slept in a featherbed the first time for more than 18 months. I caught the severest cold I ever experienced. The next day we took the train for Clifton Station. Arriving at Muscatine (the home of our then Col. Beach), the citizens had prepared a dinner for our boys in a large hall about a block from the railroad station. It was reported that the train would be held until we got dinner. So we all went to the hall and had just begun eating when editors announced the train was going. We all made a rush for the train, Jake caught it, I with many others got left. Here Jake and I separated very suddenly. Shortly afterwards he moved with his father to Marysville Missouri. I return to the hall and ate my dinner. The citizens telegraphed to Davenport for an extra train to take those who were left to the stations along the road where they belong. I arrived at Clifton a little after dark, and walked to Columbus city, about 3 mile and stayed overnight with relatives, arriving at home about noon the next day.

P.56

At home I found the vacancy and the family circle that none could fail mother and my younger sister had died while I was gone I have always thought that when a mother dies the strongest family tie is broken, and my experience during the past two years more strongly confirm the thot.