Cerro Gordo County Iowa

Part of the IAGenWeb Project

|

The Globe-Gazette

by Deb Nicklay

MASON CITY — Ten years after his brother, John, left home for service in the Iraq War, Phil Sanchez of Mason City was still at a loss as to what to do with the letter left in his care. “It sat on my buffet, in the Bible that belonged to my uncle” for years, he said. John wrote the letter “in case he didn’t come back,” said Phil. Until this week, it was never opened — in fact, John said he had forgotten he’d ever written it. As it turned out, the letter, written out of fear of death, became a family memento that spoke of love and proud service. The story of the letter is just one measure of relationships forged — and lost — during the Iraq War. It is 10 years ago this month the Iowa Army National Guard’s 1133rd Transportation Co., based in Mason City, began its service in that conflict. It marked the start of long and often lonely months of hauling supplies over thousands of miles in sweltering heat; of building new relationships in a foreign land — and bearing up under the weight of heartbreaking tragedy.

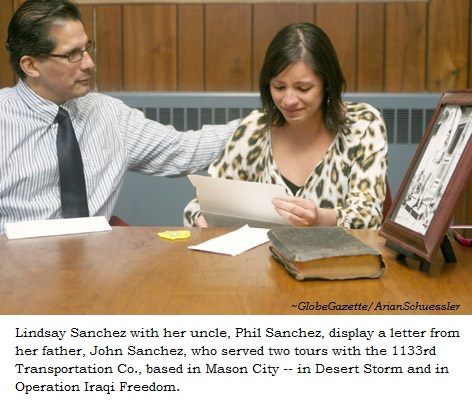

Phil Sanchez once more pulled out the letter, written by his brother John. John, now 57, had written the letter upon his departure from the U.S., in April 2003. But John did return home safely in 2004 and the letter sat mostly forgotten in the Bible. John’s company landed in Kuwait in April 2003; later, the unit traveled into Iraq and was based at Logistical Base Seitz, just outside of Baghdad. John drove with fellow Guardsman Larry Deetz. “I was proud of the service — and it was really something to travel to such a different land and culture,” he said during a telephone interview last week. After his return home, John worked for the Transportation Security Administration and then later as a correctional officer in the Iowa Correctional Institution for Women in Mitchellville, where he still works. He lives in Pleasant Hill with his wife, Julia, and their daughter, Ireland, 4. When Phil finally asked John about the letter, John suggested Phil throw the letter away, but Phil hesitated. He knew the letter was a piece of family history — and that opening it provided a rare opportunity to read what a serviceman was thinking as he headed to war. After some discussion, and with John’s blessing, Phil and John’s daughter, Lindsay, opened the letter at the Globe Gazette on Thursday. John could not be present for the opening, but would learn of its contents later. Lindsay read the letter aloud and was quickly overcome by tears. John’s message was one clearly written by a loving dad, filled with paternal entreaties: Be safe, don’t be afraid to take chances, know that you were loved. “I will always be with you,” he wrote. John Sanchez also wrote about his service. “As far as this war that is raging, it is right and just. Freedom is not cheap. My father, who I am very proud of, helped preserve that and so did countless others. “His efforts on Normandy gave me my life that I lived. Anyone that cannot see the evil and the insane loss of human rights is blind. “Two of the most important sacrifices in life are to give your life in defending your country and losing your life in protecting your child. I believe I have given both.” The reading “was powerful; it was visceral,” said Phil. Lindsay, 27, was impressed with the “care that my father took to write it all out; to say what he said. My father is not a man of many words,” she said. The letter was another chapter in the Sanchez family’s history. They understand the cost paid during wartime. The Bible in which John’s letter was held belonged to Albert Chavez, John and Phil’s uncle, who fought in both World War II and in Korea. Chavez was the brother of their mother, Mary. Chavez was taken prisoner in January 1951 in Korea. Mary received her brother’s last letter, written on the day he was captured. “Once again, here are a few lines merely to let you know all is well with me,” Chavez wrote, according to stories written about Chavez in the Globe Gazette years ago. After an eight-hour firefight with North Korean forces, Chavez and fellow soldiers were captured. Chavez died four months later of malnutrition in the prison camp. Phil and John’s father, the late Merno Sanchez, survived his landing on Omaha Beach during the horrific Normandy invasion, in June 1944. More than 5,000 American and Allied troops died during the invasion. Memories of the war often returned to his father, Phil said. “My dad hardly ever talked about it, but I remember him saying once that when he heard thunder, it reminded him of the big guns,” Phil said. Another time, Phil said, he found his father sitting at the dinner table, head in hands, as a thunderstorm raged outside. “He didn’t say anything, but I always thought of that night, that he was hearing the guns,” he said. John returned home for the last time in 2004 to his family’s welcoming arms. It marked the end of his two overseas tours with the 1133rd. Lindsay remembered both departures. “I’d say, ‘Don’t go,’ and he’s say, ‘I have to.’ I feel so blessed that he returned home.” John recalled landing on U.S. soil after his last deployment — a memory that clearly has not dimmed. “It was wonderful,” he exclaimed. However, he admitted that the impact of his service remains. “To this day, I find myself always making myself aware of my surroundings — looking over my shoulder, checking out who is standing behind me. “It’s something that has never gone away. I guess there are some things that just never leave you.”

Photograph courtesy of Globe-Gazette

|