Cerro Gordo County Iowa

Part of the IAGenWeb Project

|

The Globe-Gazette

MASON CITY — A plaque in the lobby of the Cerro Gordo County Courthouse honors the men and women from the county who have given their lives in military service. Eighteen names are enshrined from the Korean War — 13 from Mason City, three from Plymouth, one from Rockwell and one from Clear Lake. Nearly 34,000 troops died in battle. Almost 20,000 died of other causes. More than 100,000 were wounded and 8,000 were declared missing in action. And yet, it has often been called “the forgotten war,” the one that occurred between World War II and Vietnam.

Rockford native joined the Navy to 'find my brother' by Ashley Miller, Tuesday, November 22, 2016

“I wasn’t allowed to answer it, but I thought I’d better, because no one was here,” Harlan said.

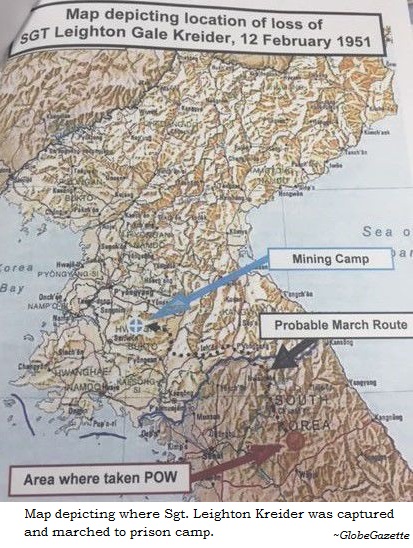

“It’s still emotional for me,” said Harlan, now 81 and living part-time in Jacksonville. “It was just one of those things you’re not ready for.” Leighton, whom Harlan remembers as a typical stubborn farm boy, joined the National Guard his senior year of high school. He later volunteered for the Army in 1949 or 1950, and was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division. During active duty, Leighton was hospitalized with hives several times before deployment to Korea in August 1950. “We thought maybe they would have let him out because of medical, but they ignored it and sent him overseas anyway,” Harlan said. As a prisoner of war, Leighton was marched north — in subfreezing conditions during which exhaustion, disease, exposure, malnutrition and lack of medical care were common — first to prisoner of war Bean Camp near Suan, arriving there in late March or early April, according to military records. Near the end of April, he was taken further north to the Mining Camp, where he died in late spring or summer 1951, around the age of 20. The Army set his date of death as Aug. 31, 1951. Harlan believes his brother’s remains are buried near the camp, which is 30 miles south of Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. At the time of Leighton’s death, his mother decided against bringing his remains to Iowa, unsure of what she’d receive. Harlan joined the Navy in 1953, with a mission in mind. “I decided I was going to go in and find my brother,” he said. “If you look back at it, it was totally impossible, because I had no control about where I would go or what I would do.” Although he and Leighton weren’t that close growing up, due to a four-year age difference, Harlan has been committed to bringing his brother’s remains home and seeking posthumous honors for his service. Harlan has attended the annual Korean War Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency briefings in Washington, D.C., since the late 1990s, hopeful Leighton’s remains will be returned to join family members. In the late 1990s North Korea turned over 200 caskets representing over 600 servicemen, which Harlan said couldn’t be identified at the time. Their bodies had been buried with chemicals that stripped DNA. New techniques have allowed researchers to identify bones, Harlan said, with more than 70 matched to servicemen this year. Some who have been identified were imprisoned near the same area as Leighton. “We’ve been told there was a 50-50 chance he was in those boxes, so we wait,” he said. If Leighton is not among those remains, Harlan said future recovery efforts in North Korea are highly unlikely due to political tension. South Korea, however, has been welcoming to veterans’ families. During a 2015 trip to the country that included memorial services and tours of the DMZ and military academies, Harlan and his wife, Connie, accepted an Ambassador of Peace medal from the government on Leighton’s behalf. The medal is considered an expression of gratitude to Americans who served in the war. “It made you feel really good, like they really cared about what we did,” Harlan said. He also lobbied for a Purple Heart for his brother. “If you died in prison camp — not of wounds — but starved to death, you didn’t get a Purple Heart,” Harlan said. He wrote letters to his congressional representatives; that stipulation was later reversed by legislation in 2008.

Photographs courtesy of Globe-Gazette

|

<