Cerro Gordo County Iowa

Part of the IAGenWeb Project

|

The Globe-Gazette

The Globe Gazette will publish 50 stories — starting on Veterans Day — about North Iowa’s Vietnam Veterans. The stories will appear on Sundays and Wednesdays. We’ll culminate this "They Served With Honor" project with a special section (publishing on the day before Memorial Day) that will include all of the profiles. It will be great keepsake and resource for family members, educators and part-time historians.

by Molly Montag, Wednesday, April 06, 2016

FERTILE — Jim Eggers spent his first night in Vietnam crouched on a rooftop in Saigon. It was February 1968, the second month of the infamous Tet Offensive.

Not exactly what Eggers had in mind when he became a Navy firefighter.

FERTILE — Jim Eggers spent his first night in Vietnam crouched on a rooftop in Saigon. It was February 1968, the second month of the infamous Tet Offensive.

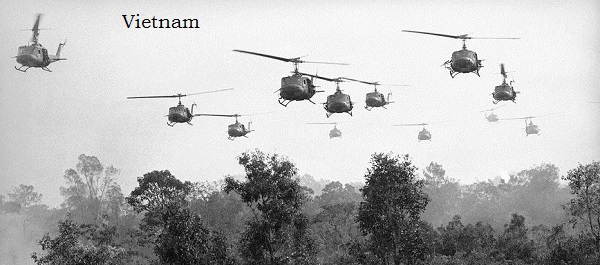

Not exactly what Eggers had in mind when he became a Navy firefighter.“I spent the night on a rooftop behind a pile of sandbags with an M-14 rifle with orders to shoot anything that moved out there and my thought was, ‘How in the hell did a sailor get in a place like this?’,” the 67-year-old Eggers said recently, laughing at the memory. Fortunately, it was only temporary. Eggers, who now lives in Fertile, was assigned to the USS Colleton, a ship with the Mobile Riverine Force. Also called the APB-36, the ship patrolled the massive Mekong River from the ocean to near the Cambodian border. It provided medical care and gun support for the Army’s 9th Infantry division. As a firefighter, Eggers was busiest when helicopters brought dead and wounded to the ship’s hospital. “If there was a crash or anything like that we made sure we’d try to do the rescue and put out the fire,” he said. “We had a few of them — they never really caught fire but they were so shot up they kind of crash-landed.” It could get very intense on deck. “There were some battles where as soon as you got one landed (and) got the people off, there’d be one right behind it waiting to come in,” Eggers said. “Then you’d unload the dead and the wounded out of that one and another one would come right behind it.” Always on the move, the Colleton was constantly trying to avoid enemy fire and mine blasts. At dark it would move to a new area to anchor for the night. “During the night we would let out our anchor chain, so that’d move us 100 yards this way, and then they’d take (the slack) back up,” Eggers explained. “Every so often they’d run the engines and it would suck the (enemy) divers up through the propellers.” One of the flotilla’s support ships, the USS Westchester County, was hit by a mine blast on Nov. 1, 1968. Eggers was sleeping in the Colleton at the time "You could feel the arch,” he said. “The whole ship raised up out of the water and came down again.” Supplies and artillery brought in by the Westchester County and other supply ships were loaded onto a barge towed behind the Colleton. The barges also had another purpose — recreation. Alcohol was banned on Navy vessels, but barges were not Navy vessels, which meant sailors could grill out, watch movies and have few beers on the barge. The crew also passed time playing football on deck. “It was more of a brawl than a football game, but we only had one football and if it went over the side into the river we’d turn the boat around and go get it,” Eggers said, chuckling. Eggers spent a year in Vietnam and then worked as a firefighting instructor for a year and half on Guam. He also spent time traveling the Pacific on a repair ship, the USS Jason, and spent two more months on a ship offshore of Vietnam in 1971. The Navy was a good experience, Eggers said, but he remains disappointed how the United States left the South Vietnamese in the lurch when it left Vietnam. He sees a lot of similarities in the ways American forces pulled out of Vietnam and, much later, in Iraq. “At the end (the South Vietnamese) didn’t have money for fuel, they didn’t have money for ammunition, because Congress cut off all the funding,” Eggers said. “And that’s why they couldn’t fight back on their own.” Photograph courtesy of Globe-Gazette

|