Cerro Gordo County Iowa

Part of the IAGenWeb Project

|

The Globe-Gazette

MASON CITY — A plaque in the lobby of the Cerro Gordo County Courthouse honors the men and women from the county who have given their lives in military service. Eighteen names are enshrined from the Korean War — 13 from Mason City, three from Plymouth, one from Rockwell and one from Clear Lake. Nearly 34,000 troops died in battle. Almost 20,000 died of other causes. More than 100,000 were wounded and 8,000 were declared missing in action. And yet, it has often been called “the forgotten war,” the one that occurred between World War II and Vietnam.

by Molly Montag, Tuesday, March 14, 2017

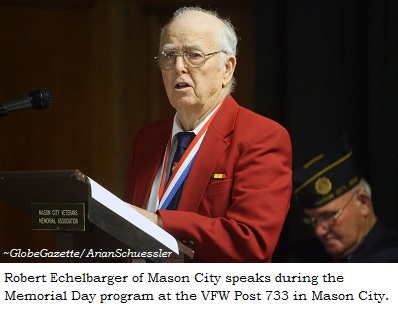

"She had a pack on her back and a white kind of gown and she has a page-boy haircut," said Echelbarger, now 88, of Mason City. "She was leaning and she had tears running down her face, and her feet had little spots of blood on them, because she was barefoot. "And, I looked at her and she looked at me and, oh, it just really hit me." Sixty years later he still remembers that face. The tears. "I can still see her," he said. That moment is one of many from the war that still sticks with Echelbarger. It was part of an nontraditional tour through the military for Echelbarger, who served during two wars. He joined the military at age 17 in June 1946. Although the fighting was essentially over, it was still during World War II because Congress hadn't declared the war over. "In those days, it was the tail end of World War II and I wanted to go to college, and my folks couldn’t afford it and I had two choices," he said. "I could either wait to be drafted or pick my branch of service." He chose the Marine Corps. He served about two years, but did something on the way out that would impact the rest of his life. He signed up for the Marine Corps Reserve. It didn't seem like a big deal at the time. It wasn't until he was in college and preparing to get married that it occurred to him there might be a problem. The war in Korea was getting bad, and Echelbarger knew they were going to need more men in uniform. "I thought of a little mistake I made when I was discharged the first time because I'd volunteered into the inactive Marine Reserve and then forgot about it, and that came back to haunt me," he said. "So, the war was really going bad and I told (his wife, Shirley) I’d thought that we shouldn’t get married, because I knew I was going to be recalled and I knew I was going to be on the front line and the war was going badly, but she insisted that we go through with it." On Oct. 12, 1950, he got word to report to Des Moines for active duty. He was in a company attached to the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment.

Echelbarger spent most of the next year trekking up and down hills. As an assistant Browning automatic rifleman, than meant he did so carrying a shoulder-operated machine gun. "That sucker was heavy," he said. The circumstances were punishing. "Living on C rations," he said. "Climbing hills and getting whittled down by the hills and getting whittled down by rear-guard action." They used water purification tablets so they could drink from streams and stayed out more than two months at a time. "Didn't wash. Didn't change clothes," he said. "All we had was the pack on our backs and our equipment." Around Thanksgiving 1951, the war of movement ended, and Echelbarger spent more time dug in around the edge of a wide valley known as the Punch Bowl. The opposing sides went back and forth across that valley, advancing and retreating back again. "So many times, so many times when I'd dig a hole in the ground I wondered if I would be in the right spot," Echelbarger said. "Because, it was just mathematics: you either were or you weren't." He lost friends, and has sheets of paper with their names and dates of the firefights that cost them their lives. Letters from Shirley, his wife, kept him going. Stationery and envelopes were among the few non-essential items he and his fellow Marines carried in the field. "The letters I got from her, they held me together," he said. "And she kept all of them." He only kept one. The rest he read three or four times and then tore up. "I didn't want them on me," he explained. "You had a little different view of life (over there)." He arrived home for good on Christmas Day 1951. For a long time Echelbarger didn't talk about Korea. On his 80th birthday, he decided it was time to tell his second wife, Sadie, who he married after Shirley died, and his children what happened while he was in Korea. The firefights. Soldiers killed. Dead civilians his company found on their patrols. Things he'd seen. Things he'd done. He told them everything. No holds barred. His motivation was simple. "I wanted them to know," he said.

Photographs courtesy of Globe-Gazette

|

<