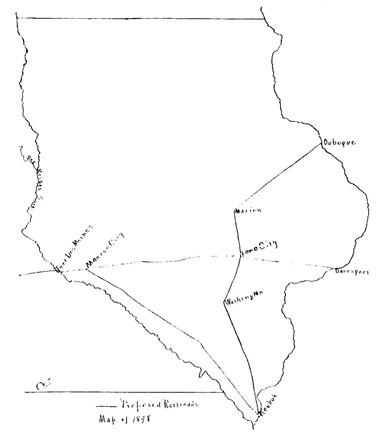

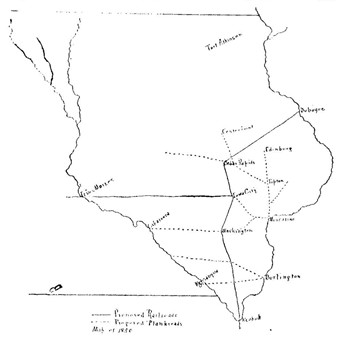

It is about three hundred miles from Lyons to Council Bluffs; and it is one hundred and thirty-five miles from Fulton to Chicago. Thus a road was laid out to connect the western side of Iowa and the Missouri River with the Great Lakes at Chicago, a scheme which has been carried out since then in many railroads.

At the beginning of the Lyons-Iowa Central railroad, men along the line subscribed about $700,000; Cedar County voted to give $50,000; Johnson County $50,000; Jasper County $42,000; Polk County $150,000,--a total of almost a million dollars. Besides it was thought that at least six more counties would subscribe as much, so that a large amount of money was promised. No doubt those who were ready to promise so much had believed that the men who were going to build the road were strictly honest and that there would be no doubt of the success of the plan. But this was only a beginning of the lessons which the men who had promised money to railroads had to learn; for the difficulties which would be in the way of constructing the first roads were not foreseen. The people were so anxious to have these built that they were ready to support almost anything which men called a railroad.

In February, 1854, nearly five hundred men were at work on the Lyons-Iowa Central road

and it was promised that there would be many more in the spring of that year. Indeed, it was said that the first seventy-five miles of the line would be completed by the first of April, 1855. Even the city of Galena, Illinois, was expecting to gain very much from the trade which would come from the rich part of the Mississippi valley through which the new line was being built. It was said also that the second division, which extended as far west as Fort Des Moines (the city of Des Moines), would be graded as fast as money was subscribed by the people, or the counties along the way.

The actual work done by these railroad laborers in 1854 is shown by great embankments still to be seen at places along the line. These were built up with wheelbarrows as long ago as 1854, and on the summit of one of them a large cottonwood tree has grown. At the streams which the road would have crossed the piles for bridges were driven in many places, and some stone work, it is said, may be found even today. Across some of the larger streams high bridges under which the steamboats could run without striking their smokestacks were to be built. The whole plan was laid out as far west as Fort Des Moines.

At a great dinner held to celebrate the arrival of the surveyors at one place, an orator had said that any man was foolish who did no believe the road would be built. Nevertheless, it happened very suddenly in the summer of 1854 that work stopped, for the builder of the line had used up all of his money; at least it was said that he had, and he wrote a letter telling how sorry he was that matters had turned out so badly. He declared, however, that the Lyons road would be built if the people were patient. Since that time men have said that the whole plan was probably a wicked scheme to rob people of good money.

The most unfortunate thing connected with the whole failure, and the one which gives the name to this chapter, was the trouble in which the laborers found themselves. There were about 2000 persons in the families of the Irish emigrants who had been brought from New York and Canada to work on this road. They were living for the time at and near Lyons, Iowa, and some were suffering great hardship. The company for which they were working had stored up supplies of groceries and drygoods which they used to pay the men. But long before the laboring men had been paid what was justly due them, these supplies were all gone. Among the articles distributed was a large quantity of calico, and from this fact the whole undertaking has been called the “Calico Road”. It was a good thing for these people that the work ceased in the summer time; for they were enabled to find work in the country near by and some of them later were among the most prosperous farmers of eastern Iowa. Coming to Iowa to work for a railroad company which had no credit, they soon found homes in the rich prairie land they had been helping to dig up to make other men rich.