|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 23, 2020

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 23, 2020

|

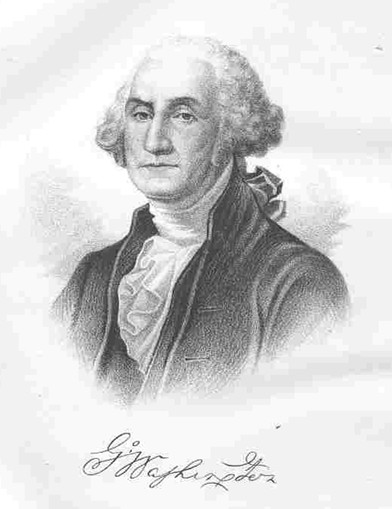

GEORGE WASHINGTON, the “Father of his Country” and its first President, 1789-’97, was born February 22, 1732, in Washington Parish, Westmoreland County, Virginia. His father, Augustine Washington, first married Jane Butler, who bore him four children, and March 6, 1830, he married Mary Ball. Of six children by his second marriage, George was the eldest, the others being Betty, Samuel, John, Augustine, Charles and Mildred, of whom the youngest died in infancy. Little is known of the early years of Washington, beyond the fact that the house in which he was born was burned during his early childhood, and that his father thereupon moved to another farm, inherited from his paternal ancestors, situated in Stafford County, on the north bank of the Rappahannock, where he acted as agent of the Principio Iron Works in the immediate vicinity, and died there in 1843.From earliest childhood George developed a noble character. He had a vigorous constitution, a fine form, and great bodily strength. His education was somewhat defective, being confined to the elementary branches taught him by his mother and at a neighboring school. He developed, however, a fondness for mathematics, and enjoyed in that branch the instructions of a private teacher. On leaving school he resided for some time at Mount Vernon with his half brother, Lawrence, who acted as his guardian, and who had married a daughter of his neighbor at Belvoir on the Potomac, the wealthy William Fairfax, for some time president of the executive council of the colony. Both Fairfax and his son-in-law, Lawrence Washington, had served with distinction in 1740 as officers of an American battalion at the siege of Carthagena, and were friends and correspondents of Admiral Vernon, for whom the latter’s residence on the Potomac has been named. George’s inclinations were for a similar career, and a midshipman’s warrant was procured for him, probably through the influence of the Admiral; but through the opposition of his mother the project was abandoned. The family connection with the Fairfaxes, however, opened another career for the young man, who, at the age of sixteen, was appointed surveyor to the immense estates of the eccentric Lord Fairfax, who was then on a visit at Belvoir, and who shortly afterward established his baronial residence at Greenway Court, in the Shenandoah Valley.

Three years were passed by young Washington in a rough frontier life, gaining experience which afterward proved very essential to him.

In 1751, when the Virginia militia were put under training with a view to active service against France, Washington, though only nineteen years of age, was appointed Adjutant with the rank of Major. In September of that year the failing health of Lawrence Washington rendered it necessary for him to seek a warmer climate, and George accompanied him in a voyage to Barbadoes. The returned early in 1752, and Lawrence shortly afterward died, leaving his large property to an infant daughter. In his will George was named one of the executors and as eventual heir to Mount Vernon, and by the death of the infant niece soon succeeded to that estate.

On the arrival of Robert Dinwiddie as Lieutenant-Governor of Virginia in 1752 the militia was reorganized, and the province divided into four districts. Washington was commissioned by Dinwiddie Adjutant-General of the Northern District in 1753, and in November of that year a most important as well as hazardous mission was assigned him. This was to proceed to the Canadian posts recently established on French Creek, near Lake Erie, to demand in the name of the King of England the withdrawal of the French from a territory claimed by Virginia. This enterprise had been declined by more than one officer, since it involved a journey through an extensive and almost unexplored wilderness in the occupancy of savage Indian tribes, either hostile to the English, or of doubtful attachment. Major Washington, however, accepted the commission with alacrity; and, accompanied by Captain Gist, he reached Fort Le Boeuf on French Creek, delivered his dispatches and received reply, which, of course, was a polite refusal to surrender the posts. This reply was of such a character as to induce the Assembly of Virginia to authorize the executive to raise a regiment of 300 men for the purpose of maintaining the asserted rights of the British crown over the territory claimed. As Washington declined to be a candidate for that post, the command of this regiment was given to Colonel Joshua Fry, and Major Washington, at his own request, was commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel. On the march to Ohio, news was received that a party previously sent to build a fort at the confluence of the Monongahela with the Ohio had been driven back by a considerable French force, which had completed the work there begun, and named it Fort Duquesne, in honor of the Marquis Duquesne, then Governor of Canada. This was the beginning of the great “French and Indian war,” which continued seven years. On the death of Colonel Fry, Washington succeeded to the command of the regiment, and so well did he fulfill his trust that the Virginia Assembly commissioned him as Commander-in-Chief of all the forces raised in the colony.

A cessation of all Indian hostility on the frontier having followed the expulsion of the French from the Ohio, the object of Washington was accomplished and he resigned his commission as Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia forces. He then proceeded to Williamsburg to take his seat in the General Assembly, of which he had been elected a member.

January 17, 1759, Washington married Mrs. Martha (Dandridge) Custis, a young and beautiful widow of great wealth, and devoted himself for the ensuing fifteen years to the quiet pursuits of agriculture, interrupted only by his annual attendance in winter upon the Colonial Legislature at Williamsburg, until summoned by his country to enter upon that other arena in which his fame was to become world wide.

It is unnecessary here to trace the details of the struggle upon the question of local self-government, which, after ten years, culminated by act of Parliament of the port of Boston. It was at the instance of Virginia that a congress of all the colonies was called to meet at Philadelphia September 5, 1774 to secure their common liberties—if possible by peaceful means. To this Congress Colonel Washington was sent as a delegate. On dissolving in October, it recommended the colonies to send deputies to another Congress the following spring. In the meantime several of the colonies felt impelled to raise local forces to repel insults and aggressions on the part of British troops, so that on the assembling of the next Congress, May 1, 1775, the war preparations of the mother country were unmistakable. The battles of Concord and Lexington had been fought. Among the earliest acts, therefore, of the Congress was the selection of a commander-in-chief of the colonial forces. This office was unanimously conferred upon Washington, still a member of the Congress. He accepted it on June 19, but on the express condition he should receive no salary.

He immediately repaired to the vicinity of Boston, against which point the British ministry had concentrated their forces. As early as April General Gage had 3,000 troops in and around this proscribed city. During the fall and winter the British policy clearly indicated a purpose to divide public sentiment and to build up a British party in the colonies. Those who sided with the ministry were stigmatized by the patriots as “Tories”, while the patriots took to themselves the name of “Whigs.”

As early as 1776 the leading men had come to the conclusion that there was no hope except in separation and independence. In May of that year Washington wrote from the head of the army in New York: “A reconciliation with Great Britain is impossible . . . . .When I took command of the army, I abhorred the idea of independence; but I am now fully satisfied that nothing else will save us.”

It is not the object of this sketch to trace the military acts of the patriot here, to whose hand the fortunes and liberties of the United States were confided during the seven years’ bloody struggle that ensued until the treaty of 1783, in which England acknowledged the independence of each of the thirteen States, and negotiated with them, jointly, as separate sovereignties. The merits of Washington as a military chieftain have been considerably discussed, especially by writers in his own country. During the war he was most bitterly assailed for incompetency, and great efforts were made to displace him; but he never for a moment lost the confidence of either the Congress or the people. December 4, 1783, the great commander took leave of his officers in most affectionate and patriotic terms, and went to Annapolis, Maryland, where the Congress of the States was in session, and to that body, when peace and order prevailed everywhere, resigned his commission and retired to Mount Vernon.

It was in 1788 that Washington was called to the chief magistracy of the nation. He received every electoral vote cast in all the colleges of the States voting for the office of President. The 4th of March, 1789, was the time appointed for the Government of the United States to begin its operations, but several weeks elapsed before quorums of both the newly constituted houses of the Congress were assembled. The city of New York was the place where the Congress then met. April 16 Washington left his home to enter upon the discharge of his new duties. He set out with a purpose of traveling privately, and without attracting any public attention; but this was impossible. Everywhere on his way he was met with thronging crowds, eager to see the man whom they regarded as the chief defender of their liberties, and everywhere he was hailed with those public manifestations of joy, regard and love which spring spontaneously from the hearts of an affectionate and grateful people. His reception in New York was marked by a grandeur and an enthusiasm never before witnessed in that metropolis. The inauguration took place April 30, in the presence of an immense multitude which had assembled to witness the new and imposing ceremony. The oath of office was administered by Robert R. Livingston, Chancellor of the State. When this sacred pledge was given, he retired with the other officials into the Senate chamber, where he delivered his inaugural address to both houses of the newly constituted Congress in joint assembly.

In the manifold details of his civil administration, Washington proved himself equal to the requirements of his position. The greater portion of the first session of the first Congress was occupied in passing the necessary statutes for putting the new organization into complete operation. In the discussions brought up in the course of this legislation the nature and character of the new system came under general review. On no one of them did any decided antagonism of opinion arise. All held it to be a limited government, clothed only with specific powers conferred by delegations from the States. There was no change in the name of the legislative department; it still remained “the Congress of the United States of America.” There was no change in the original flag of the country, and none in the seal, which still remains with the Grecian escutcheon borne by the eagle, with other emblems, under the great and expressive motto, “E Pluribus Unum.”

The first division of parties arose upon the manner of construing the powers delegated, and they were first styled “strict constructionists: and “latitudinarian constructionists.” The former were for confining the action of the Government strictly within its specific and limited sphere, while the others were for enlarging its powers by inference and implications. Hamilton and Jefferson, both members of the first cabinet, were regarded as the chief leaders, respectively, of these rising antagonistic parties, which have existed under different names, from that day to this. Washington was regarded as holding a neutral position between them, though, by mature deliberation, he vetoed the first apportionment bill, in 1790, passed by the party headed by Hamilton, which was based upon a principle constructively leading to centralization of consolidation. This was the first exercise of the veto power under the present Constitution. It created considerable excitement at the time. Another bill was soon passed in pursuance of Mr. Jefferson’s views, which has been adhered to in principle in every apportionment act passed since.

At the second session of the new Congress, Washington announced the gratifying fact of “the accession of North Carolina” to the Constitution of 1787, and June 1 of the same year he announced by special message the like “accession of the state of Rhode Island,” with his congratulations on the happy event which “united under the general Government” all the States which were originally confederated.

In 1792, at the second Presidential election, Washington was desirous to retire; but he yielded to the general wish of the country, and was again chosen President by the unanimous vote of every electoral college. At the third election, 1796, he was again most urgently entreated to consent to remain in the executive chair. This he positively refused. In September, before the election, he gave to his countrymen his memorable Farewell Address, which in language, sentiment and patriotism was a fit and crowning glory of his illustrious life. After March 4, 1797, he again retired to Mount Vernon for peace, quiet and repose.

His administration for the two terms had been successful beyond the expectation and hopes of even the most sanguine of his friends. The finances of the country were no longer in an embarrassed condition, the public credit was fully restored, life was given to every department of industry, the workings of the new system in allowing Congress to raise revenue from duties on imports proved to be not only harmonious in its federal action, but astonishing in its results upon the commerce and trade of all the States. The exports from the Union increased from $19,000,000 to over $56,000,000 per annum, while the imports increased in about the same proportion. Three new members had been added to the Union. The progress of the States in their new career under their new organization thus far was exceedingly encouraging, not only to the friends of liberty within their own limits, but to their sympathizing allies in all climes and countries.

Of the call again made on this illustrious chief to quit his repose at Mount Vernon and take command of all the United States forces, with the rank of Lieutenant-General, when war was threatened with France in 1798, nothing need here be stated, except to note the fact as an unmistakable testimonial of the high regard in which he was still held by his countrymen, of all shades of political opinion. He patriotically accepted this trust, but a treaty of peace put a stop to all action under it. He again retired to Mount Vernon, where, after a short and severe illness, he died December 14, 1799, in the sixty-eighth year of his age. The whole country was filled with gloom by this said intelligence. Men of all parties in politics and creeds in religion, in every State in the Union, united with Congress in “paying honor to the man, first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

His remains were deposited in a family vault on the banks of the Potomac at Mount Vernon, where they still lie entombed.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~