|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

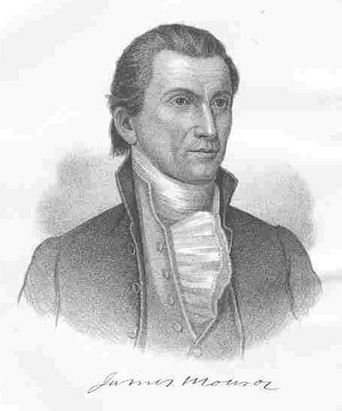

JAMES MONROE, the fifth President of the United States, 1817-’25, was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, April 28, 1758. He was a son of Spence Monroe, and a descendant of a Scottish cavalier family. Like all his predecessors thus far in the Presidential chair, he enjoyed all the advantages of education which the country could then afford. He was early sent to a fine classical school, and at the age of sixteen entered William and Mary College. In 1776, when he had been in college but two years, the Declaration of Independence was adopted, and our feeble militia, without arms, ammunition or clothing, were struggling against the trained armies of England. James Monroe left college, hastened to General Washington’s headquarters at New York and enrolled himself as a cadet in the army.At Trenton Lieutenant Monroe so distinguished himself, receiving a wound in his shoulder, that he was promoted to a Captaincy. Upon recovering from his wound, he was invited to act as aide to Lord Sterling, and in that capacity he took an active part in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown and Monmouth. At Germantown he stood by the side of Lafayette when the French Marquis received his wound. General Washington, who had formed a high idea of young Monroe’s ability, sent him to Virginia to raise a new regiment, of which he was to be Colonel; but so exhausted was Virginia at that time that the effort proved unsuccessful. He, however, received his commission.

Finding no opportunity to enter the army as a commissioned officer, he returned to his original plan of studying law, and entered the office of Thomas Jefferson, who was then Governor of Virginia. He developed a very noble character, frank, manly and sincere. Mr. Jefferson said of him:

“James Monroe is so perfectly honest that if his soul were turned inside out there would not be found a spot on it.”

In 1782 he was elected to the Assembly of Virginia, and was also appointed a member of the Executive Council. The next year he was chosen delegate to the Continental Congress for a term of three years. He was present at Annapolis when Washington surrendered his commission of Commander-in-Chief.

With Washington, Jefferson and Madison he felt deeply the inefficiency of the old Articles of Confederation, and urged the formation of a new Constitution, which should invest the Central Government with something like national power. Influenced by these views, he introduced a resolution that Congress should be empowered to regulate trade, and to lay an impost duty of five per cent. The resolution was referred to a committee of which he was chairman. The report and the discussion which rose upon it led to the convention of five States at Annapolis, and the consequent general convention of Philadelphia, which, in 1787, drafted the Constitution of the United States.

At this time there was a controversy between New York and Massachusetts in reference to their boundaries. The high esteem in which Colonel Monroe was held is indicated by the fact that he was appointed one of the judges to decide the controversy. While in New York attending Congress, he married Miss Kortright, a young lady distinguished alike for her beauty and accomplishments. For nearly fifty years this happy union remained unbroken. In London and in Paris, as in her own country, Mrs. Monroe won admiration and affection by the loveliness of her person, the brilliancy of her intellect, and the amiability of her character.

Returning to Virginia, Colonel Monroe commenced the practice of law at Fredericksburg. He was very soon elected to a seat in the State Legislature, and the next year he was chosen a member of the Virginia convention which was assembled to decide upon the acceptance or rejection of the Constitution which had been drawn up at Philadelphia, and was now submitted to the several States. Deeply as he felt the imperfections of the old Confederacy, he was opposed to the new Constitution, thinking, with many other of the Republican party, that it gave too much power to the Central Government, and not enough to the individual States.

In 1789 he became a member of the United States Senate, which office he held acceptably to his constituents and with honor to himself for four years.

Having opposed the Constitution as not leaving enough power with the States, he, of course, became more and more identified with the Republican party. Thus he found himself in cordial co-operation with Jefferson and Madison. The great Republican party became the dominant power which ruled the land.

George Washington was then President. England had espoused the cause of the Bourbons against the principles of the French Revolution. President Washington issued a proclamation of neutrality between these contending powers. France had helped us in the struggle for our liberties. All the despotisms of Europe were now combined to prevent the French from escaping from tyranny a thousandfold worse than that which we had endured. Colonel Monroe, more magnanimous than prudent, was anxious that we should help our old allies in their extremity. He violently opposed the President’s proclamation as ungrateful and wanting in magnanimity.

Washington, who could appreciate such a character, developed his calm, serene, almost divine greatness by appointing that very James Monroe, who was denouncing the policy of the Government, as the Minister of that Government to the republic of France. He was directed by Washington to express to the French people our warmest sympathy, communicating to them corresponding resolves approved by the President, and adopted by both houses of Congress.

Mr. Monroe was welcomed by the National Convention in France with the most enthusiastic demonstrations of respect and affection. He was publicly introduced to that body, and received the embrace of the President, Merlin de Douay, after having been addressed in a speech glowing with congratulations, and with expressions of desire that harmony might ever exist between the two nations. The flags of the two republics were intertwined in the hall of the convention. Mr. Monroe presented the American colors, and received those of France in return. The course which he pursued in Paris was so annoying to England and to the friends of England in this country that, near the close of Washington’s administration, Mr. Monroe, was recalled.

After his return Colonel Monroe wrote a book of 400 pages, entitled “A View of the Conduct of the Executive in Foreign Affairs.” In this work he very ably advocated his side of the question; but, with the magnanimity of the man, he recorded a warm tribute to the patriotism, ability and spotless integrity of John Jay, between whom and himself there was intense antagonism; and in subsequent years he expressed in warmest terms his perfect veneration for the character of George Washington.

Shortly after his return to this country Colonel Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia, and held that office for three years, the period limited by the Constitution. In 1802 he was an Envoy to France, and to Spain in 1805, and was Minister to England in 1803. In 1806 he returned to his quiet home in Virginia, and with his wife and children and an ample competence from his paternal estate, enjoyed a few years of domestic repose.

In 1809 Mr. Jefferson’s’ second term of office expired, and many of the Republican party were anxious to nominate James Monroe as his successor. The Majority were in favor of Mr. Madison. Mr. Monroe withdrew his name and was soon after chosen a second time Governor of Virginia. He soon resigned that office to accept the position of Secretary of State, offered him by President Madison. The correspondence which he then carried on with the British Government demonstrated that there was no hope of any peaceful adjustment of our difficulties with the cabinet of St. James. War was consequently declared in June, 1812. Immediately after the sack of Washington the Secretary of War resigned and Mr. Monroe, at the earnest request of Mr. Madison, assumed the additional duties of the War Department, without resigning his position as Secretary of State. It has been confidently stated, that, had Mr. Monroe’s energies been in the War Department a few months earlier, the disaster at Washington would not have occurred.

The duties now devolving upon Mr. Monroe were extremely arduous. Ten thousand men, picked from the veteran armies of England, were sent with a powerful fleet to New Orleans to acquire possession of the mouths of the Mississippi. Our finances were in the most deplorable condition. The treasury was exhausted and our credit gone. And yet it was necessary to make the most rigorous preparations to meet the foe. In this crisis James Monroe, the Secretary of War, with virtue unsurpassed in Greek or Roman story, stepped forward and pledged his own individual credit as subsidiary to that of the nation, and thus succeeded in placing the city of New Orleans in such a posture of defense, that it was enabled successfully to repel the invader.

Mr. Monroe was truly the armor-bearer of President Madison, and the most efficient business man in his cabinet. His energy in the double capacity of Secretary, both of State and War, pervaded all the departments of the country. He proposed to increase the army to 100,000 men, a measure which he deemed absolutely necessary to save us from ignominious defeat, but which, at the same time, he knew would render his name so unpopular as to preclude the possibility of his being a successful candidate for the Presidency.

The happy result of the conference at Ghent in securing peace rendered the increase of the army unnecessary; but it is not too much to say that James Monroe placed in the hands of Andrew Jackson the weapon with which to beat off the foe at New Orleans. Upon the return of peace Mr. Monroe resigned the department of war, devoting himself entirely to the duties of Secretary of State. These he continued to discharge until the close of President Madison’s administration, with zeal which was never abated, and with an ardor of self-devotion which made him almost forgetful of the claims of fortune, health or life.

Mr. Madison’s second term expired in March, 1817, and Mr. Monroe succeeded to the Presidency. He was a candidate of the Republican party, now taking the name of the Democratic Republican. In 1821 he was re-elected, with scarcely any opposition. Out of 232 electoral votes, he received 231. The slavery question, which subsequently assumed such formidable dimensions, now began to make its appearance. The State of Missouri, which had been carved out of that immense territory which we had purchased of France, applied for admission to the Union, with a slavery Constitution. There were not a few who foresaw the evils impending. After the debate of a week it was decided that Missouri could not be admitted into the Union with slavery. This important question was at length settled by a compromise proposed by Henry Clay.

The famous “Monroe Doctrine,” of which so much has been said, originated in this way: In 1823 it was rumored that the Holy Alliance was about to interfere to prevent the establishment of Republican liberty in the European colonies of South America. President Monroe wrote to his old friend Thomas Jefferson for advice in the emergency. In his reply under date of October 24, Mr. Jefferson writes upon the supposition that our attempt to resist this European movement might lead to war:

“Its object is to introduce and establish the American system of keeping out of our land all foreign powers; of never permitting those of Europe to intermeddle with the affairs of our nation. It is to maintain our own principle, not to depart from it.”

December 2, 1823, President Monroe sent a message to Congress, declaring it to be the policy of this Government not to entangle ourselves with the broils of Europe, and not to allow Europe to interfere with the affairs of nations on the American continent; and the doctrine was announced, that any attempt on the part of the European powers “to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere would be regarded by the United States as dangerous to our peace and safety.”

March 4, 1825, Mr. Monroe surrendered the presidential chair to his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, and retired, with the universal respect of the nation, to his private residence at Oak Hill, Loudoun County, Virginia. His time had been so entirely consecrated to his country, that he had neglected his pecuniary interests, and was deeply involved in debt. The welfare of his country had ever been uppermost in his mind.

For many years Mrs. Monroe was in such feeble health that she rarely appeared in public. In 1830 Mr. Monroe took up his residence with his son-in-law in New York, where he died on the 4th of July, 1831. The citizens of New York conducted his obsequies with pageants more imposing than had ever been witnessed there before. Our country will ever cherish his memory with pride, gratefully enrolling his name in the list of its benefactors, pronouncing him the worthy successor of the illustrious men who had preceded him in the presidential chair.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~