|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

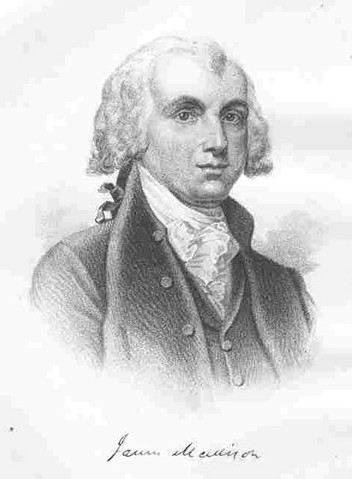

JAMES MADISON, the fourth President of the United States, 1809-’17, was born at Port Conway, Prince George County, Virginia, March 16, 1751. His father, Colonel James Madison, was a wealthy planter, residing upon a very fine estate called “Montpelier,” only twenty-five miles from the home of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. The closest personal and political attachment existed between these illustrious men from their early youth until death.James was the eldest of a family of seven children, four sons and three daughters, all of whom attained maturity. His early education was conducted mostly at home, under a private tutor. Being naturally intellectual in his tastes, he consecrated himself with unusual vigor to study. At a very early age he made considerable proficiency in Greek, Latin, French and Spanish languages. In 1769 he entered Princeton College, New Jersey, of which the illustrious Dr. Weatherspoon was then President. He graduated in 1771, with a character of the utmost purity, and a mind highly disciplined and stored with all the learning which embellished and gave efficiency to his subsequent career. After graduating he pursued a course of reading for several months, under the guidance of President Weatherspoon, and in 1772 returned to Virginia, where he continued in incessant study for two years, nominally directed to the law, but really including extended researches in theology, philosophy and general literature.

The Church of England was the established church in Virginia, invested with all the prerogatives and immunities which it enjoyed in the fatherland, and other denominations labored under serious disabilities, the enforcement of which was rightly or wrongly characterized by them as persecution. Madison took a prominent stand in behalf of the removal of all disabilities, repeatedly appeared in the court of his own county to defend the Baptist nonconformists, and was elected from Orange County to the Virginia Convention in the spring of 1766, when he signalized the beginning of his public career by procuring the passage of an amendment to the Declaration of Rights as prepared by George Mason, substitution for “toleration” a more emphatic assertion of religious liberty.

In 1776 he was elected a member of the Virginia Convention to frame the Constitution of the State. Like Jefferson, he took but little part in the public debates. His main strength lay in his conversational influence and in his pen. In November, 1777, he was chosen a member of the Council of State, and in March, 1780, took his seat in the Continental Congress, where he first gained prominence through his energetic opposition to the issue of paper money by the States. He continued in Congress three years, one of its most active and influential members.

In 1784 Mr. Madison was elected a member of the Virginia Legislature. He rendered important service by promoting and participating in that revision of the statues which effectually abolished the remnants of the feudal system subsistent up to that time in the form of entails, primogeniture, and State support given the Anglican Church; and his “Memorial and Remonstrance” against a general assessment for the support of religion is one of the ablest papers which emanated from his pen. It settled the question of the entire separation of church and State of Virginia.

Mr. Jefferson says of him, in allusion to the study and experience through which he had already passed:

“Trained in these successive schools, he acquired a habit of self-possession which placed at ready command the rich resources of his luminous and discriminating mind and of his extensive information, and rendered him the first of every assembly of which he afterward became a member. Never wandering from his subject into vain declamation, but pursuing it closely in language pure, classical and copious, soothing always the feelings of his adversaries by civilities and softness of expression, he rose to the eminent station which he held in the great National Convention of 1787; and in that of Virginia, which followed, he sustained the new Constitution in all its parts, bearing off the palm against the logic of George Mason and the fervid declamation of Patrick Henry. With these consummate powers were united a pure and spotless virtue which no calumny has ever attempted to sully. Of the power and polish of his pen, and of the wisdom of his administration in the highest office of the nation, I need say nothing. They have spoken, and will forever speak, for themselves.”

In January, 1786, Mr. Madison took the initiative in proposing a meeting of State Commissioners to devise measures for more satisfactory commercial relations between the States. A meeting was held at Annapolis to discuss this subject, and but five States were represented. The convention issued another call, drawn up by Mr. Madison, urging all the States to send their delegates to Philadelphia, in May, 1787, to draught a Constitution for the United States. The delegates met at the time appointed, every State except Rhode Island being represented. George Washington was chosen president of the convention, and the present constitution of the United States was then and there formed. There was no mind and no pen more active in framing this immortal document than the mind and pen of James Madison. He was, perhaps, its ablest advocate in the pages of the Federalist.

Mr. Madison was a member of the first four Congresses, 1789-’97, in which he maintained a moderate opposition to Hamilton’s financial policy. He declined the mission to France and the Secretaryship of State, and, gradually identifying himself with the Republican party, became from 1792 its avowed leader. In 1796 he was its choice for the Presidency as successor to Washington. Mr. Jefferson wrote: “There is not another person in the United States with whom, being placed at the helm of our affairs, my mind would be so completely at rest for the fortune of our political bark.” But Mr. Madison declined to be a candidate. His term in Congress had expired, and he returned from New York to his beautiful retreat at Montpelier.

In 1794 Mr. Madison married a young widow of remarkable powers of fascination — Mrs. Todd. She was born in 1767, in Virginia, of Quaker parents, and had been educated in the strictest rules of that sect. When but eighteen years of age she married a young lawyer and moved to Philadelphia, where she was introduced to brilliant scenes of fashionable life. She speedily laid aside the dress and address of the Quakeress, and became one of the most fascinating ladies of the republican court. In New York, after the death of her husband, she was the belle of the season and was surrounded with admirers. Mr. Madison won the prize. She proved an invaluable helpmate. In Washington she was the life of society. If there was any diffident, timid young girl just making her appearance, she found in Mrs. Madison an encouraging friend.

During the stormy administration of John Adams Madison remained in private life, but was the author of the celebrated “Resolutions of 1798,” adopted by the Virginia Legislature, in condemnation of the Alien and Sedition laws, as well as of the “report” in which he defended those resolution, which is, by many, considered his ablest State paper.

The storm passed away; the Alien and Sedition laws were repealed, John Adams lost his re-election, and in 1801 Thomas Jefferson was chosen President. The great reaction in public sentiment which seated Jefferson in the presidential chair was largely owing to the writings of Madison, who was consequently well entitled to the post of Secretary of State. With great ability he discharged the duties of this responsible office during the eight years of Mr. Jefferson’s’ administration.

As Mr. Jefferson was a widower, and neither of his daughters could be often with him, Mrs. Madison usually presided over the festivities of the White House; and as her husband succeeded Mr. Jefferson, holding his office for two terms, this remarkable woman was the mistress of the presidential mansion for sixteen years.

Mr. Madison being entirely engrossed by the cares of his office, all the duties of social life devolved upon his accomplished wife. Never were such responsibilities more ably discharged. The most bitter foes of her husband and of the administration were received with the frankly proffered hand and the cordial smile of welcome; and the influence of this gentle woman in allaying the bitterness of party rancor became a great and salutary power in the nation.

As the term of Mr. Jefferson’s Presidency drew near its close, party strife was roused to the utmost to elect his successor. It was a death-grapple between the two great parties the Federal and Republican. Mr. Madison was chosen President by an electoral vote of 122 to 53, and was inaugurated March 4, 1809, at a critical period, when the relations of the United States with Great Britain were becoming embittered, and his first term was passed in diplomatic quarrels, aggravated by the act of non-intercourse of May, 1810, and finally resulting in a declaration of war.

On the 18th of June, 1812, President Madison gave his approval to an act of Congress declaring war against Great Britain. Notwithstanding the bitter hostility of the Federal party to the war, the country in general approved; and in the autumn Madison was re-elected to the Presidency by 128 electoral votes to 89 in favor of George Clinton.

March 4, 1817, Madison yielded the Presidency to his Secretary of State and intimate friend, James Monroe, and retired to his ancestral estate at Montpelier, where he passed the evening of his days surrounded by attached friends and enjoying the merited respect of the whole nation. He took pleasure in promoting agriculture, as president of the county society, and in watching the development of the University of Virginia, of which he was long rector and visitor. In extreme old age he sat in 1829 as a member of the convention called to reform the Virginia Constitution, where his appearance was hailed with the most genuine interest and satisfaction, though he was too infirm to participate in the active work of revision. Small in stature, slender and delicate in form, with a countenance full of intelligence, and expressive alike of mildness and dignity, he attracted the attention of all who attended the convention, and was treated with the utmost deference. He seldom addressed the assembly, though he always appeared self-possessed, and watched with unflagging interest the progress of every measure. Though the convention sat sixteen weeks, he spoke only twice; but when he did speak, the whole house paused to listen. His voice was feeble though his enunciation was very distinct. One of the reporters, Mr. Stansbury, relates the following anecdote of Mr. Madison’s last speech:

“The next day, as there was a great call for it, and the report had not been returned for publication, I sent my son with a respectful note, requesting the manuscript. My son was a lad of sixteen, whom I had taken with me to act as amanuensis. On delivering my note, he was received with the utmost politeness, and requested to come up into Mr. Madison’s room and wait while his eye ran over the paper, as company had prevented his attending to it. He did so, and Mr. Madison sat down to correct the report. The lad stood near him so that his eye fell on the paper. Coming to a certain sentence in the speech, Mr. Madison erased a word and substituted another; but hesitated, and not feeling satisfied with the second word, drew his pen through it also. My son was young, ignorant of the world, and unconscious of the solecism of which he was about to be guilty, when, in all simplicity, he suggested a word. Probably no other person then living would have taken such a liberty. But the sage, instead of regarding such an instruction with a frown, raised his eyes to the boy’s face with a pleased surprise, and said, ‘Thank you, sir; it is the very word,’ and immediately inserted it. I saw him the next day, and he mentioned the circumstance, with a compliment on the young critic.

Mr. Madison died at Montpelier, June 28, 1836, at the advanced age of eighty-five. While not possessing the highest order of talent, and deficient in oratorical powers, he was pre-eminently a statesman, of a well-balanced mind. His attainments were solid, his knowledge copious, his judgement generally sound, his powers of analysis and logical statement rarely surpassed, his language and literary style correct and polished, his conversation witty, his temperament sanguine and trustful, his integrity unquestioned, his manners simple, courteous and winning. By these rare qualities he conciliated the esteem not only of friends, but of political opponents, in a greater degree than any American statesman in the present century.

Mrs. Madison survived her husband thirteen years, and died July 12, 1849, in the eighty-second year of her age. She was one of the most remarkable women our country has produced. Even now she is admiringly remembered in Washington as “Dolly Madison,” and it is fitting that her memory should descend to posterity in company with that of the companion of her life.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~