|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah January 8, 2021

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah January 8, 2021

|

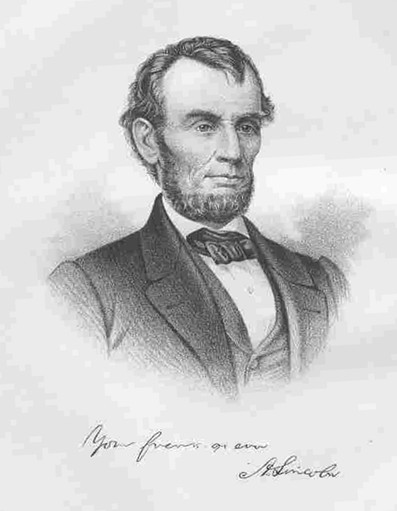

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, the sixteenth President of the United States, 1861-‘5, was born February 12, 1809, in Larue (then Hardin) County, Kentucky, in a cabin on Nolan Creek, three miles west of Hudgenville. His parents were Thomas and Nancy (Hanks) Lincoln. Of his ancestry and early years the little that is known may best be given in his own language: “My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families — second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks, some of whom now remain in Adams and others in Macon County, Illinois. My paternal grandfather, Abraham Lincoln, emigrated from Rockbridge County, Virginia, to Kentucky in 1781 or 1782, where, a year or two later, he was killed by Indians – not in battle, but by stealth, when he was laboring to open a farm in the forest. His ancestors, who were Quakers, went to Virginia from Berks County, Pennsylvania. An effort to identify them with the New England family of the same name ended in nothing more definite than a similarity of Christian names in both families, such an Enoch, Levi, Mordechai, Solomon, Abraham and the like. My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age, and he grew up, literally, without education. He removed from Kentucky to what is now Spencer County, Indiana, in my eighth year. We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union. It was a wild region, with bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew to manhood.“There were some schools, so called, but no qualification was ever required of a teacher beyond ‘reading’, writing’, and ciphering’ to the rule of three’. If a straggler, supposed to understand Latin, happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education. Of course, when I came of age I did not know much. Still, somehow, I could read, write and cipher to the rule of three, and that was all. I have not been to school since. The little advance I now have upon this store of education I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity. I was raised to farm-work, which I continued till I was twenty-two. At twenty-one I came to Illinois and passed the first year in Macon County. Then I got to New Salem, at that time in Sangamon, now in Menard County, where I remained a year as a sort of clerk in a store.

“Then came the Black Hawk war, and I was elected a Captain of volunteers — as success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since. I went the campaign, was elated; ran for the Legislature the same year (1832) and was beaten, the only time I have ever been beaten by the people. The next and three succeeding biennial elections I was elected to the Legislature, and was never a candidate afterward.

“During this legislative period I had studied law, and removed to Springfield to practice it. In 1846 I was elected to the Lower House of Congress; was not a candidate for re-election. From 1849 to 1854, inclusive, I practiced the law more assiduously than ever before. Always a Whig in politics, and generally on the Whig elector tickets, making active canvasses, I was losing interest in politics, when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise roused me again. What I have done since is pretty well known.”

The early residence of Lincoln in Indiana was sixteen miles north of the Ohio River, on Little Pigeon Creek, one and a half miles east of Gentryville, within the present township of Carter. Here his mother died October 5, 1818, and the next year his father married Mrs. Sally (Bush) Johnston, of Elizabethtown, Kentucky. She was an affectionate foster-parent, to whom Abraham was indebted for his first encouragement to study. He became an eager reader, and the few books owned in the vicinity were many times perused. He worked frequently for the neighbors as a farm laborer; was for some time clerk in a store at Gentryville; and became famous throughout that region for his athletic powers, his fondness for argument, his inexhaustible fund of humorous anecdote, as well as for mock oratory and the composition of rude satirical verses. In 1828 he made a trading voyage to New Orleans as “bow-hand” on a flatboat; removed to Illinois in 1830; helped his father build a log house and clear a farm on the north fork of Sangamon River, ten miles west of Decatur, and was for some time employed in splitting rails for the fences — a fact which was prominently brought forward for a political purpose thirty years later.

In the spring of 1851, he, with two of his relatives, was hired to build a flatboat on the Sangamon River and navigate it to New Orleans. The boat “stuck” on a mill-dam, and was got off with great labor through an ingenious mechanical device which some years later led to Lincoln’s taking out a patent for “an improved method for lifting vessels over shoals.” This voyage was memorable for another reason — the sight of slaves chained, maltreated and flogged at New Orleans was the origin of his deep convictions upon the slavery question.

Returning from this voyage he became a resident for several years at New Salem, a recently settled village on the Sangamon, where he was successively a clerk, grocer, surveyor and postmaster, and acted as pilot to the first steamboat that ascended the Sangamon. Here he studied law, interested himself in local politics after his return from the Black Hawk war, and became known as an effective “stump-speaker”. The subject of his first political speech was the improvement of the channel of the Sangamon, and the chief ground on which he announced himself (1832) a candidate for the Legislature was his advocacy of this popular measure, on which subject his practical experience made him the highest authority.

Elected to the Legislature in 1832 as a “Henry Clay Whig”, he rapidly acquired that command of language and that homely but forcible rhetoric which, added to his intimate knowledge of the people from which he sprang, made him more than a match in debate for his few well-educated opponents.

Admitted to the bar in 1837 he soon established himself at Springfield, where the State capital was located in 1839, largely through his influence; became a successful pleader in the State, Circuit and District Courts; married in 1842 a lady belonging to a prominent family in Lexington, Kentucky; took an active part in the Presidential campaigns of 1840 and 1844 as candidate for elector on the Harrison and Clay tickets, and in 1846 was elected to the United States House of Representatives over the celebrated Peter Cartwright. During his single term in Congress he did not attain any prominence.

He voted for the reception of anti-slavery petitions for the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia and for the Wilmot proviso; but was chiefly remembered for the stand he took against the Mexican war. For several years there-after he took comparatively little interest in politics, but gained a leading position at the Springfield bar. Two or three non-political lectures and an eulogy on Henry Clay (1852) added nothing to his reputation.

In 1854 the repeal of the Missouri Compromise by the Kansas-Nebraska act aroused Lincoln from his indifference, and in attacking that measure he had the immense advantage of knowing perfectly well the motives and the record of its author Stephen A. Douglas, of Illinois, then popularly designated as the “Little Giant”. The latter came to Springfield in October, 1843, on the occasion of the State Fair to vindicate his policy in the Senate, and the “Anti-Nebraska” Whigs, remembering that Lincoln had often measured his strength with Douglas in the Illinois Legislature and before the Springfield Courts, engaged him to improvise a reply. This speech, in the opinion of those who heard it, was one of the greatest efforts of Lincoln’s life; certainly the most effective in his whole career. It took the audience by storm, and from that moment it was felt that Douglas had met his match. Lincoln was accordingly selected as the Anti-Nebraska candidate for the United States Senate in place of General Shields, whose term expired March 4, 1855, and led to several ballots; but Trumbull was ultimately chosen.

The second conflict on the soil of Kansas, which Lincoln had predicted, soon began. The result was the disruption of the Whig and the formation of the Republican party. At the Bloomington State Convention in 1856, where the new party first assumed form in Illinois, Lincoln made an impressive address, in which for the first time he took distinctive ground against slavery in itself.

At the National Republican Convention at Philadelphia, June 17, after the nomination of Fremont, Lincoln was put forward by the Illinois delegation for the Vice-Presidency, and received on the first ballot 110 votes against 259 for William L. Dayton. He took a prominent part in the canvass, being the electoral ticket.

In 1858 Lincoln was unanimously nominated by the Republican State Convention as its candidate for the United States Senate in place of Douglas, and in his speech of acceptance used the celebrated illustration of a “house divided against itself” on the slavery question, which was, perhaps, the cause of his defeat. The great debate carried on at all the principal towns of Illinois between Lincoln and Douglas as rival Senatorial candidates resulted at the time in the election of the latter; but being widely circulated as a campaign document, it fixed the attention of the country upon the former, as the clearest and most convincing exponent of Republican doctrine.

Early in 1859 he began to be named in Illinois as a suitable Republican candidate for the Presidential campaign of the ensuing year, and a political address delivered at the Cooper Institute, New York, February 17, 1860, followed by similar speeches at New Haven, Hartford and elsewhere in New England, first made him known at to the Eastern States in the light by which he had long been regarded at home. By the Republican State Convention, which met at Decatur, Illinois, May 9 and 10, Lincoln was unanimously endorsed for the Presidency. It was on this occasion that two rails, said to have been split by his hands thirty years before, were brought into the convention, and the incident contributed much to his popularity. The National Republican Convention at Chicago, after spirited efforts made in favor of Seward, Chase and Bates, nominated Lincoln for the Presidency, with Hannibal Hamlin for Vice-President, at the same time adopting a vigorous anti-slavery platform.

The Democratic party having been disorganized and presenting two candidates, Douglas and Breckenridge, and the remnant of the “American” party having put forward John Bell, of Tennessee, the Republican victory was an easy one, Lincoln being elected November 6 by a large plurality, comprehending nearly all the Northern States, but none of the Southern. The secession of South Carolina and the Gulf States was the immediate result, followed a few months later by that of the border slave States and the outbreak of the great civil war.

The life of Abraham Lincoln became thenceforth merged in the history of his country. None of the details of the vast conflict which filled the remainder of Lincoln’s life can here be given. Narrowly escaping assassination by avoiding Baltimore on his way to the capital, he reached Washington February 23, and was inaugurated President of the United States March 4, 1861.

In his inaugural address he said: “I hold, that in contemplation of universal law and the Constitution of the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied if not expressed in the fundamental laws of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination. I therefore consider that in view of the Constitution and the laws, the Union is unbroken, and to the extent of my ability I shall take care, as the Constitution enjoins upon me, that the laws of the United States be extended in all the States. In doing this there need be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none unless it be forced upon the national authority. The power conferred to me will be used to hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the Government, and to collect the duties and imports, but beyond what may be necessary for these objects there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere. In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-country-men, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect and defend it.”

He called to his cabinet his principal rivals for the Presidential nomination — Seward, Chase, Cameron and Bates; secured the co-operation of the Union Democrats, headed by Douglas; called out 75,000 militia from the several States upon the first tiding of the bombardment of Fort Sumter, April 15; proclaimed a blockade of the Southern posts April 19; called an extra session of Congress for July 4, from which he asked and obtained 400,000 men and $400,000,000 for the war; placed McClellan at the head of the Federal army on General Scott’s resignation, October 31; appointed Edwin M. Stanton Secretary of War, January 14, 1862, and September 22, 1862, issued a proclamation declaring the freedom of all salves in the States and parts of States then in rebellion from and after January 1, 1863. This was the crowning act of Lincoln’s career — the act by which he will be chiefly known through all future time — and it decided the war.

October 16, 1863, President Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers to replace those whose term of enlistment had expired; made a celebrated and touching, though brief, address at the dedication of the Gettysburg military cemetery, November 19, 1863; commissioned Ulysses S. Grant Lieutenant-General and Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the United States, March 9, 1864; was re-elected President in November of the same year, by a large majority over General McClellan, with Andrew Johnson, of Tennessee, as Vice-President; delivered a very remarkable address at his second inauguration, March 4, 1865, visited the army before Richmond the same month; entered the capital of the Confederacy the day after its fall, and upon the Surrender of General Robert E Lee’s army, April 9, was actively engaged in devising generous plans for the reconstruction of the Union, when, on the evening of Good Friday, April 14, he was shot in his box at Ford’s Theatre, Washington, by John Wilkes Booth, a fanatical actor, and expired early on the following morning, April 15. Almost simultaneously a murderous attack was made upon William H. Seward, Secretary of State.

At noon on the 15th of April Andrew Johnson assumed the Presidency, and active measures were taken which resulted in the death of Booth and the execution of his principal accomplices.

The funeral of President Lincoln was conducted with unexampled solemnity and magnificence. Impressive services were held in Washington, after which the sad procession proceeded over the same route he had traveled four years before, from Springfield to Washington. In Philadelphia his body lay in state in Independence Hall, in which he had declared before his first inauguration “that I would sooner be assassinated than to give up the principles of the Declaration of Independence.” He was buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery, near Springfield, Illinois, on May 4, where a monument emblematic of the emancipation of the slaves and the restoration of the Union mark his resting place.

The leaders and citizens of the expiring Confederacy expressed genuine indignation at the murder of a generous political adversary. Foreign nations took part in mourning the death of a statesman who had proved himself a true representative of American nationality. The freedmen of the South almost worshiped the memory of their deliverer; and the general sentiment of the great Nation he had saved awarded him a place in its affections, second only to that held by Washington.

The characteristics of Abraham Lincoln have been familiarly known throughout the civilized world. His tall, gaunt, ungainly figure, homely countenance, and his shrewd mother-wit, shown in his celebrated conversations overflowing in humorous and pointed anecdote, combined with an accurate, intuitive appreciation of the questions of the time, are recognized as forming the best type of a period of American history now rapidly passing away.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~