|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah January 8, 2021

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah January 8, 2021

|

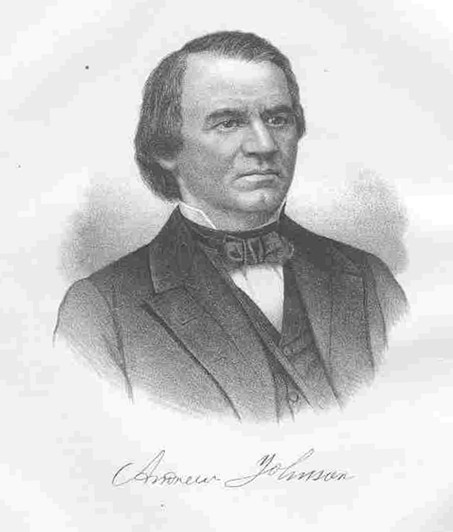

ANDREW JOHNSON, the seventeenth President of the United States, 1865-‘9, was born at Raleigh, North Carolina, December 29, 1808. His father died when he was four years old, and in his eleventh year he was apprenticed to a tailor. He never attended school, and did not learn to read until late in his apprenticeship, when he suddenly acquired a passion for obtaining knowledge, and devoted all his spare time to reading.After working two years as a journeyman tailor at Lauren’s Court-House, South Carolina, he removed, in 1826, to Greenville, Tennessee, where he worked at his trade and married. Under his wife’s instructions he made rapid progress in his education, and manifested such an intelligent interest in local politics as to be elected as “workingmen’s candidate” alderman, in 1828, and mayor in 1830, being twice re-elected to each office.

During this period he cultivated his talents as a public speaker by taking part in a debating society, consisting largely of students of Greenville College. In 1835, and again in 1839, he was chosen to the lower house of the Legislature, as a Democrat. In 1841 he was elected State Senator, and in 1843, Representative in Congress, being re-elected four successive periods, until 1853, when he was chosen Governor of Tennessee. In Congress he supported the administration of Tyler and Polk in their chief measures, especially the annexation of Texas, the adjustment of the Oregon boundary, the Mexican war, and the tariff of 1846.

In 1855 Mr. Johnson was re-elected Governor, and in 1857 entered the United States Senate, where he was conspicuous as an advocate of retrenchment and of the Homestead bill, and as an opponent of the Pacific Railroad. He was supported by the Tennessee delegation to the Democratic convention in 1860 for the Presidential nomination, and lent his influence to the Breckenridge wing of that party.

When the election of Lincoln had brought about the first attempt at secession in December, 1860, Johnson took in the Senate a firm attitude for the Union, and in May, 1861, on returning to Tennessee, he was in imminent peril of suffering from popular violence for his loyalty to the “old flag.” He was the leader of the Loyalists’ convention of East Tennessee, and during the following winter was very active in organizing relief for the destitute loyal refugees from that region, his own family being among those compelled to leave.

By his course in this crisis Johnson came prominently before the Northern public, and when in March, 1862, he was appointed by President Lincoln military Governor of Tennessee, with the rank of Brigadier-General, he increased in popularity by the vigorous and successful manner in which he labored to restore order, protect Union men and punish marauders. On the approach of the Presidential campaign of 1864, the termination of the war being plainly foreseen, and several Southern States being partially reconstructed, it was felt that the Vice-Presidency should be given to a Southern man of conspicuous loyalty, and Governor Johnson was elected on the same platform and ticket as President Lincoln; and on the assassination of the latter succeeded to the Presidency, April 15, 1865. In a public speech two days later he said: “The American people must be taught, if they do not already feel, that treason is a crime and must be punished; that the Government will not always bear with its enemies; that it is strong, not only to protect, but to punish. In our peaceful history treason has been almost unknown. The people must understand that it is the blackest of crimes, and will be punished.” He then added the ominous sentence: “In regard to my future course, I make no promises, no pledges.” President Johnson retained the cabinet of Lincoln, and exhibited considerable severity toward traitors in his earlier acts and speeches, but he soon inaugurated a policy of reconstruction, proclaiming a general amnesty to the late Confederates, and successively establishing provisional Governments in the Southern States. These States accordingly claimed representation in Congress in the following December, and the momentous question of what should be the policy of the victorious Union toward its late armed opposition was forced upon that body.

Two considerations impelled the Republican majority to reject the policy of President Johnson: First, an apprehension that the chief magistrate intended to undo the results of the war in regard to slavery; and, second, the sullen attitude of the South, which seemed to be plotting to regain the policy which arms had lost. The credentials of the Southern members elect were laid on the table, a civil rights bill and a bill extending the sphere of the Freedman’s Bureau were passed over the executive veto, and the two highest branches of the Government were soon in open antagonism. The action of Congress was characterized by the President as a “new rebellion.” In July the cabinet was reconstructed, Messrs. Randall, Stanbury and Browning taking the places of Messrs. Denison, Speed and Harlan, and an unsuccessful attempt was made by means of a general convention in Philadelphia to form a new party on the basis of the administration policy.

In an excursion to Chicago for the purpose of laying a corner-stone of the monument to Stephen A. Douglas, President Johnson, accompanied by several members of the cabinet, passed through Philadelphia, New York and Albany, in each of which cities, and in other places along the route, he made speeches justifying and explaining his own policy, and violently denouncing the action of Congress.

August 12, 1867, President Johnson removed the Secretary of War, replacing him by General Grant. Secretary Stanton retired under protest, based upon the tenure-of-office act which had been passed the preceding March. The President then issued a proclamation declaring the insurrection at an end, and that “peace, order, tranquility and civil authority existed in and throughout the United States.” Another proclamation enjoined obedience to the Constitution and the laws, and an amnesty was published September 7, relieving nearly all the participants in the late Rebellion from the disabilities thereby incurred, on condition of taking the oath to support the Constitution and the laws.

In December Congress refused to confirm the removal of Secretary Stanton, who thereupon resumed the exercise of his office; but February 21, 1868, President Johnson again attempted to remove him, appointing General Lorenzo Thomas in his place. Stanton refused to vacate his post, and was sustained by the Senate.

February 24 the House of Representatives voted to impeach the President for “high crime and misdemeanors,” and March 5 presented eleven articles of impeachment on the ground of his resistance to the executive of the acts of Congress, alleging, in addition to the offense lately committed, his public expressions of contempt for Congress, in “certain intemperate, inflammatory and scandalous harangues” pronounced In August and September, 1866, and thereafter declaring that the Thirty-ninth Congress of the United States was not a competent legislative body, and denying its power to propose Constitutional amendments. March 23 the impeachment trial began, the President appearing by counsel, and resulted in acquittal, the vote lacking one of the two-thirds vote required for conviction.

The remainder of President Johnson’s term of office was passed without any such conflicts as might have been anticipated. He failed to obtain a nomination for re-election by the Democratic party, though receiving sixty-five votes on the first ballot. July 4 and December 25 new proclamations of pardon to the participants in the late Rebellion were issued, but were of little effect. On the accession of General Grant to the Presidency, March 4, 1869, Johnson returned to Greenville, Tennessee. Unsuccessful in 1870 and 1872 as a candidate respectively for United States Senator and Representative, he was finally elected to the Senate in 1875, and took his seat in the extra session of March, in which his speeches were comparatively temperate. He died July 31, 1875, and was buried at Greenville.

President Johnson’s administration was a peculiarly unfortunate one. That he should so soon become involved in bitter feud with the Republican majority in Congress was certainly a surprising and deplorable incident; yet, in reviewing the circumstances after a lapse of so many years, it is easy to find ample room for a charitable judgment of both the parties in the heated controversy, since it cannot be doubted that any President, even Lincoln himself, had he lived, must have sacrificed a large portion of his popularity in carrying out any possible scheme of reconstruction.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~