|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

of

GREENE and CARROLL COUNTIES, IOWA

The Lewis Publishing Company, 1887

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

Carroll County IAGenWeb |

Transcribed by Sharon Elijah December 26, 2020

|

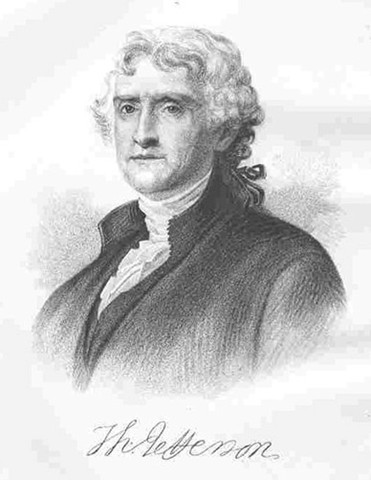

THOMAS JEFFERSON, the third President of the United States, 1801-‘9, was born April 2, 1743, the eldest child of his parents, Peter and Jane (Randolph) Jefferson, near Charlottesville, Albemarle County, Virginia, upon the slopes of the Blue Ridge. When he was fourteen years of age, his father died, leaving a widow and eight children. She was a beautiful and accomplished lady, a good letter-writer, with a fund of humor, and an admirable housekeeper. His parents belonged to the Church of England, and are said to be of Welch origin. But little is known of them, however.Thomas was naturally of a serious turn of mind, apt to learn, and a favorite at school, his choice studies being mathematics and the classics. At the age of seventeen he entered William and Mary College, in an advanced class, and lived in rather an expensive style, consequently being much caressed by gay society. That he was not ruined, is proof of his stamina of character. But during his second year he discarded society, his horses and even his favorite violin, and devoted thenceforward fifteen hours a day to hard study, becoming extraordinarily proficient in Latin and Greek authors.

On leaving college, before he was twenty-one, he commenced the study of law, and pursued it diligently until he was well qualified for practice, upon which he entered in 1767. By this time he was also versed in French, Spanish, Italian and Anglo-Saxon, and in the criticism of the fine arts. Being very polite and polished in his manner, he won the friendship of all whom he met. Though able with his pen, he was not fluent in public speech.

In 1769 he was chosen a member of the Virginia Legislature, and was the largest slave-holding member of that body. He introduced a bill empowering slave-holders to manumit their slaves, but it was rejected by an overwhelming vote.

In 1770 Mr. Jefferson met with a great loss; his house at Shadwell was burned, and his valuable library of 2,000 volumes was consumed. But he was wealthy enough to replace the most of it, as from his 5,000 acres tilled by slaves and his practice at the bar his income amounted to about $5,000 a year.

In 1772 he married Mrs. Martha Skelton, a beautiful, wealthy and accomplished young widow, who owned 40,000 acres of land and 130 slaves, yet he labored assiduously for the abolition of slavery. For his new home he selected a majestic rise of land upon his large estate at Shadwell, called Monticello, whereon he erected a mansion of modest yet elegant architecture. Here he lived in luxury, indulging his taste in magnificent, high-blooded horses.

At this period the British Government gradually became more insolent and oppressive toward the American colonies, and Mr. Jefferson was ever one of the most foremost to resist its encroachments. From time to time he drew up resolutions of remonstrance, which were finally adopted, thus proving his ability as a statesman and as a leader. By the year 1774 he became quite busy, both with voice and pen, in defending the right of the colonies to defend themselves. His pamphlet entitled: “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” attracted much attention in England. The following year he, in company with George Washington, served as an executive committee in measures to defend by arms the State of Virginia. As a Member of the Congress, he was not a speechmaker, yet in conversation and upon committees he was so frank and decisive that he always made a favorable impression. But as late as the autumn of 1775 he remained in hopes of reconciliation with the parent country.

At length, however, the hour arrived for draughting the “Declaration of Independence,” and this responsible task was devolved upon Jefferson. Franklin, and Adams suggested a few verbal corrections before it was submitted to Congress, which was June 28, 1776, only six days before it was adopted. During the three days of the fiery ordeal of criticism through which it passed in Congress, Mr. Jefferson opened not his lips. John Adams was the main champion of the Declaration on the floor of Congress. The signing of this document was one of the most solemn and momentous occasions ever attended to by man. Prayer and silence reigned throughout the hall, and each signer realized that if American independence was not finally sustained by arms he was doomed to the scaffold.

After the colonies became independent States, Jefferson resigned for a time his seat in Congress in order to aid in organizing the government of Virginia, of which State he was chosen Governor in 1779, when he was thirty-six years of age. At this time the British had possession of Georgia and were invading South Carolina, and at one time a British officer, Tarleton, sent a secret expedition to Monticello to capture the Governor. Five minutes after Mr. Jefferson escaped with his family, his mansion was in possession of the enemy! The British troops also destroyed his valuable plantation on the James River. “Had they carried off the slaves,” said Jefferson, with characteristic magnanimity, “to give them freedom, they would have done right.”

The year 1781 was a gloomy one for the Virginia Governor. While confined to his secluded home in the forest by a sick and dying wife, a party arose against him throughout the State, severely criticizing his course as Governor. Being very sensitive to reproach, this touched him to the quick, and the heap of troubles then surrounding him nearly crushed him. He resolved, in despair, to retire from public life for the rest of his days. For weeks Mr. Jefferson sat lovingly, but with a crushed heart, at the bedside of his sick wife, during which time unfeeling letters were sent to him, accusing him of weakness and unfaithfulness to duty. All this, after he had lost so much property and at the same time done so much for his country! After her death he actually fainted away, and remained so long insensible that it was feared he never would recover! Several weeks passed before he could fully recover his equilibrium. He was never married a second time.

In the spring of 1782 the people of England compelled their king to make to the Americans overtures of peace, and in November following, Mr. Jefferson was reappointed by Congress, unanimously and without a single adverse remark, minister plenipotentiary to negotiate a treaty.

In March, 1784, Mr. Jefferson was appointed on a committee to draught a plan for the government of the Northwestern Territory. His slavery-prohibition clause in that plan was stricken out by the pro-slavery majority of the committee; but amid all the controversies and wrangles of politicians, he made it a rule never to contradict anybody or engage in any discussion as a debater.

In company with Mr. Adams and Dr. Franklin, Mr. Jefferson was appointed in May, 1784, to act as minister plenipotentiary in the negotiation of treaties of commerce with foreign nations. Accordingly, he went to Paris and satisfactorily accomplished his mission. The suavity and high bearing of his manner made all the French his friends; and even Mrs. Adams at one time wrote to her sister that he was “the chosen of the earth.” But all the honors that he received, both at home and abroad, seemed to make no change in the simplicity of his republican tastes. On his return to America, he found two parties respecting the foreign commercial policy, Mr. Adams sympathizing with that in favor of England and himself favoring France.

On the inauguration of General Washington as President, Mr. Jefferson was chosen by him for the office of Secretary of State. At this time the rising storm of the French Revolution became visible, and Washington watched it with great anxiety. His cabinet was divided in their views of constitutional government was well as regarding the issues in France. General Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, was the leader of the so-called Federal party, while Mr. Jefferson was the leader of the Republican party. At the same time there was a strong monarchial party in this country, with which Mr. Adams sympathized. Some important financial measures, which were proposed by Hamilton and finally adopted by the cabinet and approved by Washington, were opposed by Mr. Jefferson; and his enemies then began to reproach him with holding office under an administration whose views he opposed. The President poured oil on the troubled waters. On his re-election to the Presidency he desired Mr. Jefferson to remain in the cabinet, but the latter sent in his resignation at two different times, probably because he was dissatisfied with some of the measures of the Government. His final one was not received until January 1, 1794, when General Washington parted from him with great regret.

Jefferson then retired to his quiet home at Monticello, to enjoy a good rest, not even reading the newspapers lest the political gossip should disquiet him. On the President’s again calling him back to the office of Secretary of State, he replied that no circumstances would ever again tempt him to engage in anything public! But, while all Europe was ablaze with war, and France in the throes of a bloody revolution and the principal theater of the conflict, a new Presidential election in this country came on. John Adams was the Federal candidate and Mr. Jefferson became the Republican candidate. The result of the election was the promotion of the latter to the Vice-Presidency, while the former was chosen President. In this contest Mr. Jefferson really did not desire to have either office, he was “so weary” of party strife. He loved the retirement of home more than any other place on the earth.

But for four long years his Vice-Presidency passed joylessly away, while the partisan strife between Federalist and Republican was ever growing hotter. The former party split and the result of the fourth general election was the elevation of Mr. Jefferson to the Presidency! with Aaron Burr as Vice-President. These men being at the head of a growing party, their election was hailed everywhere with joy. On the other hand, many of the Federalists turned pale, as they believed what a portion of the pulpit and the press had been preaching—that Jefferson was a “scoffing atheist,” a “Jacobin,” the “incarnation of all evil,” “breathing threatening and slaughter!”

Mr. Jefferson’s inaugural address contained nothing but the noblest sentiments, expressed in fine language, and his personal behavior afterward exhibited the extreme of American, democratic simplicity. His disgust of European court etiquette grew upon him with age. He believed that General Washington was somewhat distrustful of the ultimate success of a popular Government, and that, imbued with a little admiration of the forms of a monarchical Government, he had instituted levees, birthdays, pompous meetings with Congress, etc. Jefferson was always polite, even to slaves everywhere he met them, and carried in his countenance the indications of an accommodating disposition.

The political principles of the Jeffersonian party now swept the country, and Mr. Jefferson himself swayed an influence which was never exceeded even by Washington. Under his administration, in 1803, the Louisiana purchase was made, for $15,000,000, the “Louisiana Territory” purchased comprising all the land west of the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean.

The year 1804 witnessed another severe loss in his family. His highly accomplished and most beloved daughter Maria sickened and died, causing as great grief in the stricken parent as it was possible for him to survive with any degree of sanity.

The same year he was re-elected to the Presidency, with George Clinton as Vice-President. During his second term our relations with England became more complicated, and on June 22, 1807, near Hampton Roads, the United States frigate Chesapeake was fired upon by the British man-of-war Leopard, and was made to surrender. Three men were killed and ten wounded. Jefferson demanded reparation. England grew insolent. It became evident that war was determined upon by the latter power. More than 1,200 Americans were forced into the British service upon the high seas. Before any satisfactory solution was reached, Mr. Jefferson’s Presidential term closed. Amid all these public excitements he thought constantly of the welfare of his family, and longed for the time when he could return home to remain. There, at Monticello, his subsequent life was very similar to that of Washington at Mt. Vernon. His hospitality toward his numerous friends, indulgence of his slaves, and misfortunes to his property, etc., finally involved him in debt. For years his home resembled a fashionable watering-place. During the summer, thirty-seven house servants were required! It was presided over by his daughter, Mrs. Randolph.

Mr. Jefferson did much for the establishment of the University at Charlottesville, making it unsectarian, in keeping with the spirit of American institutions, but poverty and the feebleness of old age prevented him from doing what he would. He even went so far as to petition the Legislature for permission to dispose of some of his possessions by lottery, in order to raise the necessary funds for home expenses. It was granted; but before the plan was carried out, Mr. Jefferson died, July 4, 1826, at 12:50 p.m.

~ * ~ * ~ * ~ * ~