![]()

Sisters Recall Fun of Clamming in Jefferson, Now a Ghost Town

|

Sisters Recall Fun of Clamming in Jefferson, Now a Ghost

Town

By Elnora Robey

New Albin, Iowa -- Though Jefferson, a southeastern Minnesota community, almost disappeared 30 years ago, life there is still vivid in the minds of two New Albin sisters. Clara Darling, 84, and Ella Zarwell, 82, were daughters of Mr. and Mrs. John Myers, whose home was one of the dozen buildings on the hillside above a steamboat landing a mile north of the state line. The buildings were removed when Highway 26 was built in the early '40s. The Myers house, in which the Zarwells also lived for a time, is now part of a house in Eitzen, Minnesota. The Darling house became part of a farm home. "After a year in a rented house, we bought this," Mrs. Darling said of the house she and her daughter, Belva, call home. Mrs. Zarwell's present home is a few blocks away.

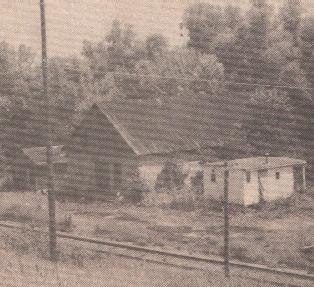

By 1942 all that was left of the steamboat landing at Jefferson was the warehouse that had served for cargo storage.

The stone warehouse once stood between the

railroad and a slough that steamboats could navigate.

The wharehouse is all that remains of what was once a small

community in southeastern Minnesota.

The railroad that went upriver had dealt a severe blow to river commerce. The river itself dealt the knockout punch when channel changes left Jefferson stranded on a silted bottom. Like many midwestern ghost towns, it had begun with an investment of capital and hope. In 1868, William Robinson and A.B. Hays built a stone warehouse on the bank of a slough north of Winnebago Creek and named it New Landing. There was no New Albin -- just a level area on a farm owned by John Ross.

Then a company was formed to build a railroad from Dubuque, Iowa to Winona, Minnesota. In November 1872 the name of Hily Ross, administratrix of John Ross, appears with those of J.A. Rhomberg, J.K. Graves, and S.H. Kinne as founders of a platted town laid out in blocks and lots on either side of the projected railroad. The last three were from Dubuque, and one can visualize their looking over the territory and deciding that this spot near the end of two valleys -- Winnebago and Oneota -- and a reasonable distance from Lansing, already thriving, and the river, a competitor, was right for a townsite.

By 1880 their town, New Albin, had a population of 423. It has remained as it was planned, a town with two business streets, a railroad park, a city park and residential streets named after trees. In a county of hilly towns, it remained on the level until recently when a street of new houses started climbing reservoir hill.

Mrs. Zarwell recalled, "We had to go to New Albin every time there was anything going on, and if the Winnebago was flooded so we couldn't walk, our dad took us by boat, landing at a sawmill that used to be on the slough below New Albin, or walked us down the track -- there were a lot of trains those days and you had to be careful." "I remember the steamboats when I was a kid," Mrs. Darling said. Grain was shipped in barges from the warehouse. Logging was a lively industry. "They'd bring in logs. Some of the men were great log rollers, and there'd be crowds watching. I'd sometimes cry because some of the men roomed at my mother's house, and I was afraid they'd get hurt. "There were no trees out in front of the warehouse then. It was all water. I must have been seven or eight."

Mrs. Zarwell recalled fixing up a fish pole from a willow, a string and a bent pin. "We caught fish, too. We were regular river rats. We'd rock the boats till they'd be full of water. None of us could swim, but no one drowned. In winter we'd have fun on the ice. Even after the steamboats couldn't come, we had one deep pool. The men sank a rail on end and attached a pole to the top to make a kind of merry-go-round. It's still there; I could still find that rail."

The community, which took the name of the township, Jefferson, seems to have been closeknit. Mrs. Darling recalled,' "Ecks lived below the school. Then Olivers lived there. Rose (Oliver) taught me to play the organ. She married a Reiser -- not related to the Reisers here -- and moved to Chicago to work on the railroad. They wanted us to come, but mother and dad didn't want to." The town's school survived almost to the end, but the store, "kept by Mrs. Hays, a nice old lady who lived upstairs," could not compete with those in New Albin and became a dance hall. The Zarwells' wedding dance was held there in 1909. Henry Zarwell did farm work, but when the Zarwell children began to reach high school age, the family moved to New Albin in 1925. Zarwell did in 1961.

The Harvey Randall house was higher on the hillside, and eventually three more houses were built. North of them were the more temporary dwellings of the native Americans. "Sometimes there were as many as 12 Indian camps," Mrs. Zarwell said. "We played with the children, they came to school, but toward fall they usually left to pick blueberries."

Visiger was another family name know in the area, and in the 1920s, New Albin was treated to a preview before the family took its tent show on the road. "Every member of that family played an instrument," Mrs. Zarwell recalled.

Lysander Darling had come clamming with his folks in a "shanty boat" and won the heart of young Clara Myers. Clamming for the manufacture of pearl buttons was the big industry of the late 1890s, but by 1913 the clam beds were becoming depleted and investigations were in progress to find a remedy. By the late 1920s clamming was no longer commercially profitable. Today most clam shells go to Japan to be used in pearl culture.

J.M. Turner established the first pearl button factory in Lansing in May 1899. It had 36 saws, and its 42 employes processed about 1,400 tons a year. Soon Capoli Button Works, with 75 year-round employes. came to South Lansing, and the New Jersey Button Works, with a cutting force of 50 men, was established. When someone discovered poultry would eat crushed clam shells, the factories had a use for a by-product. By 1913 Turner's plant was turning out 12 tons of crushed shells each day. In summer, boats of the clammers dotted the river; in winter they were used for ice fishing. Sometimes the women went clamming with the men, more often they went on their own. "We used to be in water to our necks all day," Mrs. Darling recalled. "I'd rather go clamming than stay home. I'd take the kids and go." Although Mrs. Zarwell didn't go too often, she enjoyed clamming. "I'd go, just for fun. We'd hang onto the side of the boat with one hand and reach into the water with the other," she said. Part of the fun was the chance of finding a pearl. "I found a big one once," Mrs. Darling smiled. "A man from Genoa gave me $225 for it. It was as big as my thumb nail; too big for a ring, so he looked for a mate to make earrings. I don't think he ever did find one to match it. One of the men found one and he and his partner sold it for $2,000." The day she found the pearl, Mrs. Darling had taken a couple of the children. "They wanted to go. I was just reaching over the side, and we'd open the clams we kept (some clams were not suitable for buttons) with an axe. The pearl was in about the second one I opened. Mr. was working on the road at the time, and one of the men took me up to tell him," she said.

Excursion boats were a feature of main channel life. Jefferson people often went across to Victory to catch the boat to La Crosse. "We were on the J.S. when it burned," Mrs. Darling said. "We'd all bought stuff; Grandma was great to shop. I had the baby buggy, and our stuff was in it. The next day there was my buggy right on top of a pile of junk. "I got separated with the baby from the others, but an acquaintance said, 'You climb down, and I'll hand down the baby.' I did, but then I got pushed in the crowd and couldn't find the baby. He was handed from person to person, and I lost him. Finally I heard a woman say, 'I wish someone would claim this baby.' I looked, and it was mine."

The Darlings lost their firstborn and a son died in World War II, but five sons and five daughters survived. Mrs. Zarwell has two sons and a daughter. Both women are 50-year members of the Royal Neighbors of America. Mrs. Darling also belongs to the VFW Auxiliary and still has a big garden. Though she is supposed to limit her horticulture to her plants, including a renowned lemon plant that produced one two-pounder, she admits she told her kids it's her yard and she'll dig in it if she wants to.

Most of Jefferson may have been knocked down and

hauled off, but these two former Jefferson residents still have

plenty of spirit and vitality.

- source: La Crosse Tribune, La Crosse, Wisconsin,

August 23, 1974

- contributed by Errin Wilker